What made film legend and Kansas native Buster Keaton so great? A new book explains

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

He was nicknamed “The Great Stone Face” in America. Called “Malec” in France. “Glo Glo” in Iceland. “Kazunk” in Liberia.

Silent film legend Buster Keaton was known all around the world by various names, but he was born Joseph Frank Keaton in tiny Piqua, Kansas.

Despite his birthplace, Keaton was more of a barnstorming entertainer with no true connection to any one place.

“It’s interesting that he is often read as a Midwesterner. He sounds like a Midwesterner when he gave interviews and in his talking pictures, and I see why Kansas claims him,” says author Dana Stevens.

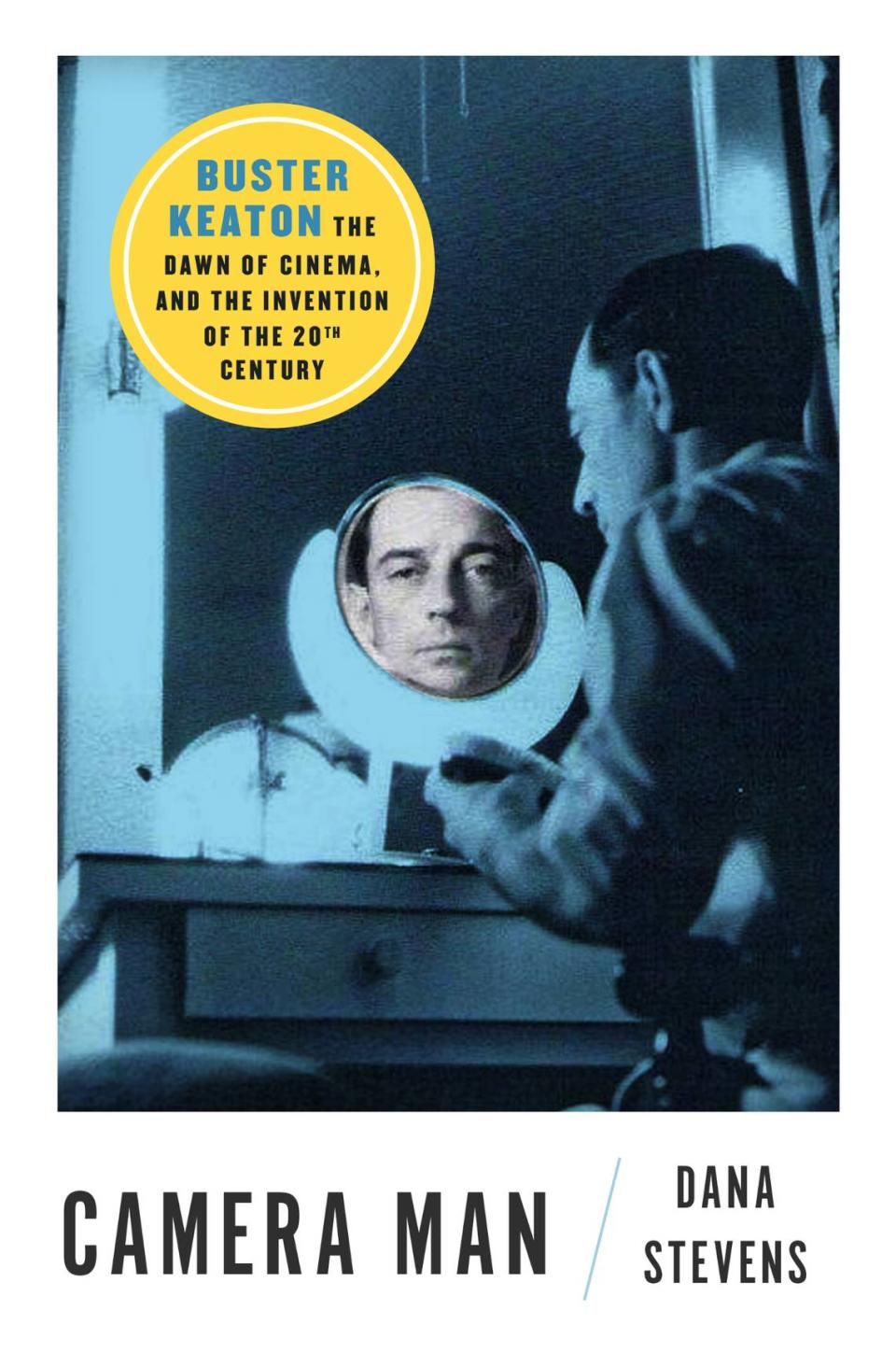

The longtime film critic for Slate, Stevens delves into the history of Keaton and the world of filmmaking, culture and society that surrounded him in the new book “Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema and the Invention of the Twentieth Century” (Atria Books), due out Jan. 25.

“Part of the mission of this book is just to be a keeper of the flame of what a great artist he was,” Stevens says via Zoom from her home in Brooklyn, New York. “To keep him alive in the imagination of people who love film as someone who’s not antiquated, who’s not a dusty, nostalgic memory to go back and revisit, but someone who’s one of the great American artists of the 20th century and beyond.”

That greatness seemed to run counter to his signature image onscreen: an innocuous working-class fellow decked in a pork pie hat and blank expression. But whether flinging himself down a steep hillside while being chased by boulders or standing perfectly still while a house collapses around him, Keaton showcased a willingness to attempt any physical challenge while combining it with innovations in the emerging craft of moviemaking.

As for that Kansas connection, it may be grounded in wishful thinking rather than veracity.

“It’s a sort of dream iconography that connects him to Kansas more than any real time he spent there,” she explains.

“As I mention early in the book, when Keaton went back to visit Piqua in later life, he wanted to leave after five minutes because there was nothing there to see. But that, I think, has less to do with Kansas or the Midwest per se than with his kind of ‘placelessness.’ As a child entertainer (in a family vaudeville act), he didn’t really grow up anywhere. He grew up on trains and theatrical boarding houses. He had a complex relationship to ‘home.’”

Much has been written on Keaton (1895-1966), considered one of the greatest actor-directors in movie history and perhaps the best physical comedian of all time. When tackling such a singular figure, Stevens had little interest in discovering new archival material or creating the definitive timeline of his every waking moment.

“I wanted to make this prismatic, essayistic series of glimpses into his life. My strength is not being an archivist or film historian. That’s not me. I’m a critic, so I had to write as a critic,” she says.

That didn’t exactly prove easy.

Stevens calls Keaton “extremely private.” He apparently left no letters behind; only one scrap of handwriting exists in his archive.

“He’s just not a word guy,” she says. “He had a personality that came across in his interviews. He was authentically himself, but he always said the same things, always told the same stories. Unfortunately, he didn’t get asked very good questions in interviews that made him push beyond those stories. And he never revealed anything about his private life.”

Instead, he was almost entirely epitomized by his expressionless facade. Hal Hinson of The Washington Post wrote, “Next to Garbo, Buster Keaton possessed the most exquisite face in the history of the movies.” Film historian Jeffrey Vance wrote that Keaton’s face “belongs on Mount Rushmore,” describing it as “at once hauntingly immovable and classically American.”

“He always had that impassive face, not just on screen but in photographs as well,” Stevens says. “If he knew a camera was on him, he would assume a personality — and he said he was doing that. I think he was asked sometimes, ‘Why don’t you smile on camera?’ And he would say, essentially, ‘That’s my brand.’”

Ultimately, this inscrutability proved to be the most challenging aspect of writing about the man.

“There’s a quote from his sister, Louise, that didn’t make it into the book, where she says, ‘You never knew what he was thinking. Never.’ And she lived with him for many years of his adult life,” Stevens says. “So if she didn’t know who he was, like, who did?

“Part of the passion that drove me to write the book was to understand who was the person who created this work, and how does it relate to his life? How does that life fit into the period of time and cultural history that he was living through?”

For modern audiences, Keaton is often lumped together with the other two great artists of the silent movie era: Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd. Film circles continually debate how to rank these icons in terms of influence and talent.

“They obviously each have their own vision, and I can understand somebody being in the Chaplin or Lloyd camp and saying they’re just as original a comic,” Stevens says.

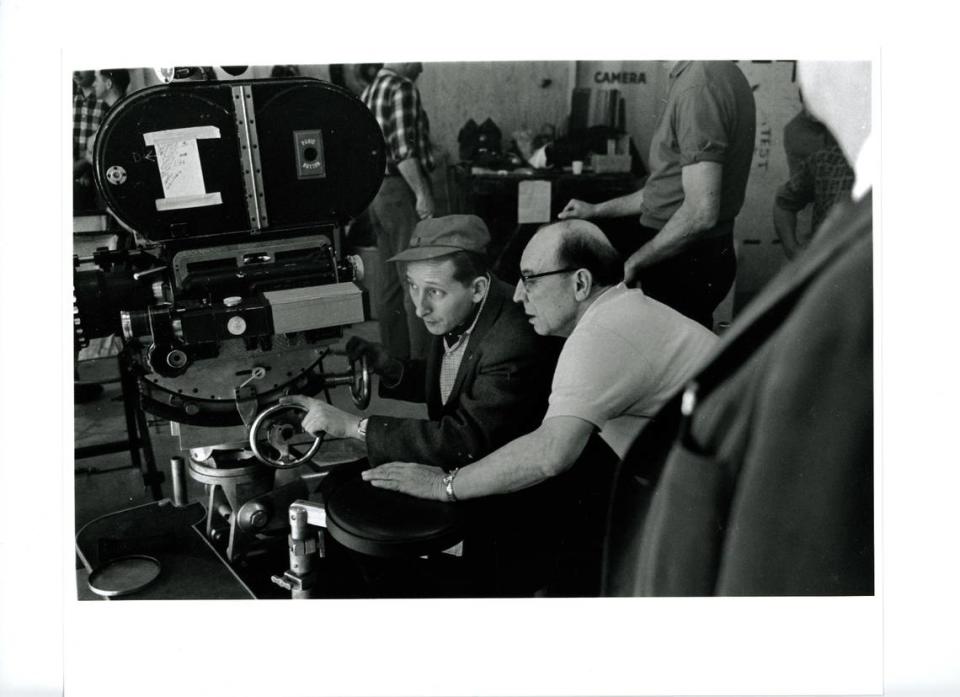

“To me, what separates Keaton is that as a director, he really stands out. He was the total package, certainly more so than Lloyd, who didn’t direct his own films. And I think more so than Chaplin, who did not distinguish himself as a director — he distinguished himself much more as a performer. Keaton was just so inventive with the camera. Even if he had not stepped in front of the camera, he would have been doing incredible things with it. He almost treated it as an extension of his own body.”

She says Keaton used technology to augment and express the same ideas his character was physically doing onscreen. Whether it was through editing or long single takes, through camera movement or complicated action staged around a static shot, the filmmaker proved an early pioneer of techniques now seen as fundamental elements of the art form.

“Today his films still resonate,” says Bob Borgen, a California-based producer who served as president of the International Buster Keaton Society from 2017 to 2018.

“His understated character and directorial technique are completely modern, with none of the sentimentality of Chaplin or Lloyd. Films like ‘The General,’ ‘The Cameraman’ and ‘Steamboat Bill, Jr.’ look like they were made today, except in black and white and silent.”

Stevens’ own introduction to the comedian occurred 25 years ago when she was studying abroad at the University of Strasbourg in France and happened upon a Keaton movie at a state-subsidized theater.

She was hooked.

Flash forward a few years, and Stevens found herself writing a poem about the star that she described as capturing “the image of Keaton hurled as a human projectile into the 20th century.” That concept became a road map for the book she would eventually write.

After poring over his cinematic catalog (19 silent short films and 10 silent features during his Golden Era of 1920-1928), Stevens cites two onscreen moments she considers favorites.

One comes from his 1926 masterpiece “The General.” A Civil War epic, the scene in question finds Keaton attempting to remove railroad ties cluttering the path of a slow-moving train he is conducting. He scampers in front of the locomotive to pick up one hefty tie, then hurls it with perfect aim and timing to knock away another.

“I love watching him do incredible things with his body,” she says. “Like throwing the railroad tie, it’s this moment when you laugh and gasp at the same. It’s one of those moments where if he’d gotten that stunt wrong, he would have died.”

The character moment she loves most comes from a scene in “The Cameraman” (which obviously inspired the title of her book).

“It’s where he sinks to his knees on the beach. He’s betrayed. It’s a very sad sight to witness because ‘The Cameraman’ is the last movie that he had much control over. In a way it feels like the last true Buster Keaton movie,” she says.

“That moment points to what a dramatic actor he could have been. He could have moved into a period of his career that was a little bit less about technical prowess, amazing stunts, gags and rescues, and he could have been a really great actor.”

A native of New York, Stevens earned a Ph.D. in comparative literature from University of California-Berkeley. She joined Slate in 2003, and has written for The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Atlantic. Additionally, she appeared multiple times as a guest on “Charlie Rose.” “Camera Man” is her first book.

Borgen says, “There are many good biographies of Keaton, but hers is like a 3D picture of Keaton and his time — how he grew up at the same time as cinema. Hers is like ‘The World of Buster Keaton,’ how he influenced it and vice versa.”

Stevens (who hopes to write a future book on England’s Bronte sisters) wants one of the launch events for “Camera Man” to involve screenings for children that showcase Keaton shorts chosen especially for their kid appeal.

“My daughter has loved (Keaton) since she was 6 years old,” she says. “Every kid understands he was a great entertainer, maybe because he entertained as a child.”

The author says there are ample opportunities for modern audiences to rediscover Keaton; almost all his motion pictures are in the public domain for free.

“If I want people to come away with something, it’s that Keaton should be a part of their vocabulary in the same way Alfred Hitchcock or Quentin Tarantino is,” Stevens says.

“They should know more than just, ‘Oh, a house fell on him in “Steamboat Bill, Jr.”’ There’s really no aspect of his filmography that isn’t worth knowing. What I want people to take away from it is: This is work that still matters.”

Jon Niccum is a filmmaker, freelance writer and author of “The Worst Gig: From Psycho Fans to Stage Riots, Famous Musicians Tell All.”

Buster Keaton in Kansas

Buster Keaton happened to be born in Piqua (pronounced Pick-way) Kansas, on Oct. 4, 1895, because his parents were passing through on their vaudeville tour. Still, southeast Kansas claims him as its own:

▪ The Piqua water department houses the Buster Keaton Museum, with photos, posters and other memorabilia. 620-468-2385.

▪ Nearby Iola, Kansas, is home to the (mostly) annual Buster Keaton Celebration, a festival of films and speakers that last fall took place online and in person at the Bowlus Fine Arts Center. 620-365-4765, bowluscenter.org.