He made history as a Black oceanographer, but he faced racial hatred in early days

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

We say it all the time: Time flies. That was never truer than when I got a call from my friend Evan Forde, saying he was retiring from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration after 50 years.

He worked in NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory on Virginia Key, and was the first Black oceanographer to explore the Atlantic’s deep canyons in a two-man submersible in 1979.

I had an immediate flashback to one of the first times I spoke with Evan. He had already been on the job for seven years when I had the opportunity to tell the world about this brilliant young oceanographer, who just happened to be Black. It is always refreshing to write about the progress of our younger generation and, in particular, young Blacks who succeed despite discrimination and other obstacles.

As I was writing this column, I thought about the late Katherine Johnson and the other Black women in NASA who were called human computers because they were so brilliant. The film, “Hidden Figures,” told the story of three Black women, especially Johnson, who were instrumental in formulating the mathematical calculations to launch astronaut John Glenn into orbit.

When I first heard the story and saw the movie — decades after I had interviewed Evan — I was both angry and proud. I was angry because the contributions these Black women had made were largely hidden from not only Black Americans, but from the entire country. I was proud because the women excelled, against all odds, including discrimination in the workplace.

Although it is much better now, the road to success for too many Black professionals, from the arts to science, has always been paved with hurdles and pitfalls. I felt that it was, and is, my duty as a Black journalist to tell their story, including Evan’s.

Born and raised in Miami

Evan is a product of Miami. He was born in the old Christian Hospital in Overtown on May 11, 1952. He is the middle child of three siblings, an older brother and a younger sister, and grew up in the old Bunche Park area of Miami Gardens, where he attended Rainbow Park Elementary. Although both his parents were teachers, Evan said he didn’t do well in elementary school.

“I was a C, D, and F student back then,” he admitted. “Our parents had married while in college. Dad had graduated and he worked days as a science teacher and as a custodian at night to afford to send our mom back to Florida A&M University to get her degree. I missed my mom terribly when she was away at school. I think that’s why I didn’t do well in elementary school.”

By the time he entered junior high school, his grades got much better. But it was a fire that destroyed his family home when he was 15 that made him realize that his life counted for something.

“I remember sitting on the ground with second-degree burns on my face and thinking: ‘I could have died and no one would have known that I was ever here [on earth],‘“ he said. “That is when I decided that I was going to do something significant in the world. At the time, I didn’t know what I would do, but I was going to make my life count for something.”

Carol City football coach key mentor

At Carol City High School, Evan joined the marching band and played football. He said it was the late Coach Vernon Wilder, who played for the team as a student and recovered a fumble that led to a state championship in 1977, who told him he was smart enough to go to college.

“I quit the band but stayed on the football team because I wanted to earn a scholarship,” Forde said.

While at Carol City High, he took a course in environmental oceanography: “I had been a fan of Jacques Cousteau since I was about 6 or 7. I never missed ‘The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau’ show.”

In the oceanography class, he learned that Columbia University had one of the best oceanography schools in the country. By then, Evan said he was nearly a straight-A student. He was accepted at Columbia, Yale and Harvard. He attended Columbia, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1974, and a master’s degree in 1976.

Evan started his NOAA career at the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory in Miami during the summer of 1973, while he was still in college. In addition to his barrier-breaking expedition on the submersible Nekton Gamma in 1979, Evan became a noted authority on marine geology and geophysics.

Today, Evan remains one of a handful of Black oceanographers in the country.

Faced discrimination, racism

“There was lots of discrimination when I started my career,” he said. “Once one of my supervisors told me he couldn’t promote me because people would say he promoted me because I was Black.

“When we went out on research ships, it was even worse. Although I was in charge, the white workers would not follow my orders. I had to use students on board to help carry out the research. It was gut wrenching, and sometimes a bit scary. After all, here I was, on a boat in the middle of the sea with white men who hated me simply because I was Black. I didn’t know if they were a part of the KKK, or what.”

During his career, he has conducted investigations in several scientific disciplines, including marine geology and geophysics, atmospheric chemistry and marine biology.

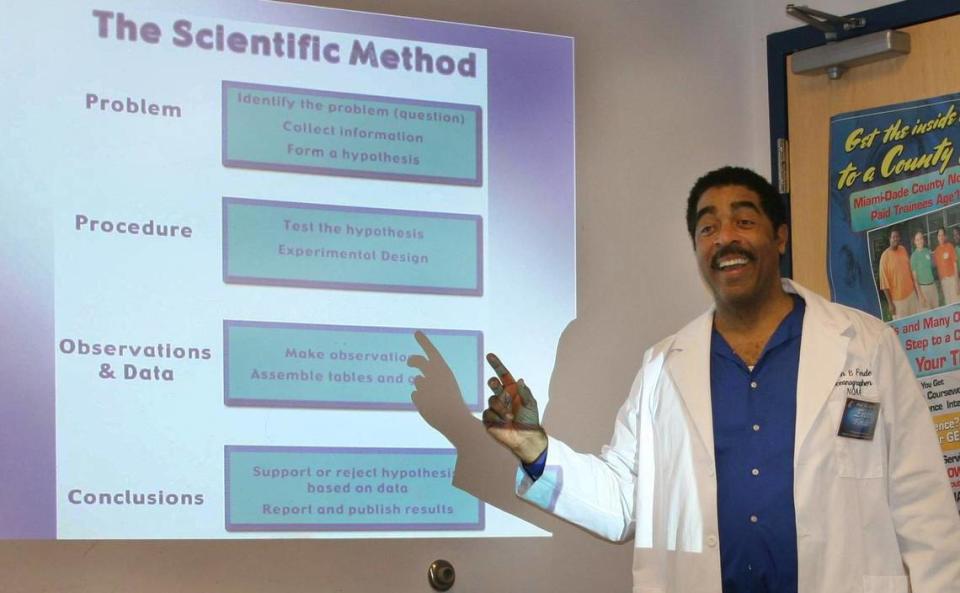

He has worked extensively in science education and taught at the graduate level at the University of Miami. He also taught an oceanography course for middle school students that was featured in Ebony Jr! nagazine’s “Science Corner” for three years. He also developed a Severe Weather Poster for NOAA that was distributed nationally and estimated to have been seen by 8 million schoolchildren each day.

Upon his retirement in December, Richard W. Spinrad, Ph.D., the Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere at NOAA, acknowledged Evan’s contribution in a letter he wrote to him:

“… Your departure from NOAA marks the end of an era and leaves us with big shoes to fill. ... You have been a strong, charismatic leader for our lab as well as a caring mentor to both your team and young scientists discovering their careers. Thank you for always bringing a collegial spirit and setting a positive work environment that fostered creativity and partnership.”

In addition to his work with NOAA, Evan, the divorced father of son Justin J. Ford, a board-certified physician in gastroenterology and in internal and obesity medicine, also found time to serve as a PTA president, Scoutmaster, youth basketball coach, Sunday School teacher, church webmaster, Neighborhood Crime Watch chairman and the photographer for the South Florida Special Olympics for 12 years.

At 71, he says he will continue working on projects to help create a better environment for humankind.