Made in Ukraine: Kyiv’s burgeoning weapons industry is enabling it to project power far beyond the front lines

In the early hours of August 29, swarms of Ukrainian drones flew across seven Russian regions. Many were intercepted; some were not.

Several reached a Russian airbase in Pskov, some 600 kilometers from the Ukrainian border, destroying two Russian military transport aircraft and damaging two more.

It was the most dramatic evidence yet of a new dimension to the 18-month conflict: Ukraine’s growing appetite to take the war to Russian territory.

Aerial and marine drones, mysterious new missiles and sabotage groups are all part of the toolkit; Russian airfields, air defenses and shipping among the targets.

Ukraine has plenty of reasons for broadening the conflict.

A win is a win wherever and whenever it occurs – whether damaging planes at a distant Russian airbase, disrupting commercial aviation and shipping, putting the residents of Russian border regions on edge or hitting Russian air defenses in Crimea.

For Ukrainians who have suffered endless drone and missile attacks, evidence of payback (albeit on a much smaller scale) is a welcome morale-booster, especially when the counteroffensive in the south is still struggling to gain traction.

President Volodymr Zelensky has been unapologetic for taking the conflict to Russian soil, saying recently: “The war is returning to the territory of Russia – to its symbolic centers and military bases, and this is an inevitable, natural and absolutely fair process.”

Attacks far from the current front lines are also evidence of an evolving Ukrainian capability to project power.

That projection very deliberately does not rely upon Western hardware but local adaptations, in terms of both technology and tactics. President Volodymyr Zelensky and Defense Minister Oleksiy Reznikov have repeatedly assured Western donors that their weapons won’t be used against targets inside Russia; that would be viewed by Moscow as an act of aggression which would make them party to the conflict.

That point was reiterated by Ukrainian presidential adviser an adviser to the Head of the President’s office, Mykhailo Podolyak this week. “Ukraine strictly adheres to the obligation not to use the weapons of its partners to strike Russian territory,” he said.

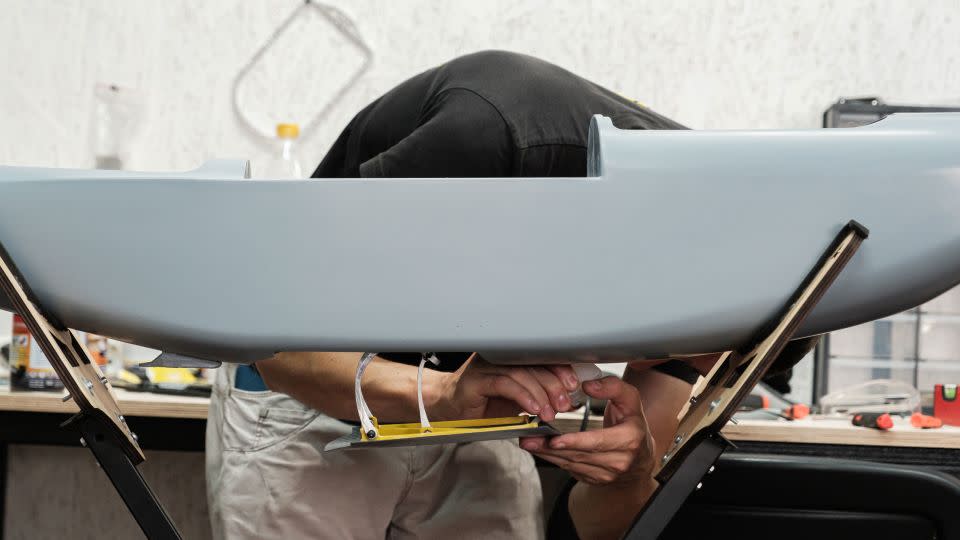

Instead, Ukraine is pushing ahead with creating a weapons industry that will provide everything from 155mm artillery shells to longer-range drones and now – it seems – a new long-range missile.

Senior Ukrainian officials have been dropping hints about the development of a new cruise missile. Oleksii Danilov, secretary of Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council, posted a video last week of the purported missile with the caption: “The President of Ukraine’s missile program in action. The tests are successful, the use is effective.”

Later he spoke of a three-year development program, “to provide a distance of thousands of kilometers, this is the work of large teams, powerful work. Now we can say we have a result.”

Zelensky himself dropped a cryptic note, congratulating the Ministry of Strategic Industries with the message: “Successful use of our long-range weapons: the target was hit 700 kilometers away!”

And Ukraine’s Center for Strategic Communication reinforced the point Friday, saying on Telegram: “Having launched a full-scale aggression, the Russians counted on their impunity: that the fighting would be localized in Ukraine, and they would feel safe in their rear.”

“The increase in range destroys the Russian illusion of security and increases the cost of aggression for the enemy,” it added.

This is clearly a developing part of Ukraine’s strategy. Podolyak said: “The war is increasingly moving to Russia’s territory, and it cannot be stopped. This is a consequence of the lost frontline component (Russia has long been fighting only in numbers and only in defense, despite all propaganda myths) and the lack of realistic… systems in the regions (including air defense).”

Central to this projection of force is an array of Ukrainian drones – in the air and at sea. The latest iterations have longer range and greater payloads than previous models, thanks to what the Ukrainians describe as a global trawl for drone technology and contracts for multiple indigenous manufacturers.

The attack on the Pskov airbase is the fruit of this labor, though just how it was executed is something of a mystery. The head of Ukrainian Defense Intelligence, Kyrylo Budanov, said that the attack was launched from within Russia, while declining to say what kind of drones were used or how many.

That may be Budonov’s flair for gamesmanship – intended to sow confusion and distrust inside Russia.

It is possible that the drones were launched from Ukrainian territory, but accurate targeting over a distance of more than 700 kilometers would require a step-change in navigational capabilities.

One Russian blogger complained that the Pskov strike indicated that Russian air defenses had not adapted to defend against repeated Ukrainian drone strikes.

The damage being done is not going to break the back of the Russian air force, but it has become a serious irritant. On August 22, at least one Tu-22M strategic bomber was set ablaze at the Soltsy-2 airbase in northern Russia; then came the Pskov attack.

All at sea

Ukraine has also invested heavily in the development of marine drones. The latest deployed carry an explosive payload of up to 400 kilograms, capable of holing a substantial vessel, and can travel hundreds of kilometers.

Early in August, one struck the Russian gas and chemical tanker SIG close to the Kerch strait, immobilizing but not sinking it. Another hit a Russian naval ship in the port of Novosibirsk.

The maritime drones in use against both Russian naval and merchant shipping in the Black Sea provide both a morale boost and complicate Russian calculations. Some Russian warships in the Black Sea have mounted machine-guns on their decks to repel what are difficult weapons to defend against.

These attacks force Russia to spend time on developing counter-measures: One recent example is being the sinking of barges close to the Kerch bridge to Crimea, in an effort to prevent it being hit again by maritime drones following the attacks in July and August.

As Mick Ryan, author of the blog Futura Doctrina and a former General in the Australian armeed forces, writes: “With almost no likelihood of developing its own conventional naval fleet to fight the Russians, the Ukrainians have developed uncrewed capabilities. While ostensibly designed to sink or damage Russian surface warships, they are also intended to have the psychological effect of dissuading the Russian ships from putting to sea.”

Similarly, Russian authorities have to devote air defenses that might be deployed in Ukraine to the Moscow region and infrastructure such as air bases, which have become a frequent target of Ukrainian attacks. Open-source reporting suggests there are at least several Pantsir-2 air defense batteries around Moscow.

The Institute for the Study of War notes that “Russian forces may have focused their air defenses on covering Moscow and somehow missed the unusually large number of Ukrainian drones that reportedly struck the Pskov airfield.”

The Ukrainians are also more focused on degrading Russian transport links, air defenses and bases in annexed Crimea. Last month, they carried out a missile strike against one of Russia’s modern S-400 air defense systems on the Crimean coast, following it up with a commando raid.

Budanov said subsequently: “We have the ability to hit any part of the temporarily occupied [Crimea] as of now. We can reach the enemy absolutely anywhere.”

Strikes at greater range are an extension of the strategy successfully employed since last year to target Russian logistics hubs, command centers and ammunition/ or fuel dumps way behind the frontlines. Longer range Western systems such as HIMARS and more recently Storm Shadows, which with a range of 250 kms have have been critical to that effort, in Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia.

Such weapons put Russian forces on notice that they are vulnerable far from the front lines. An attack on a Russian command center in occupied Berdiansk in July killed a senior Russian general; another in January obliterated a barracks in Donetsk, with considerable loss of life.

The drone operations and even the development of new missiles won’t determine the course of the war. Success or failure for the Ukrainians will be determined by the amount of territory reclaimed from Russian occupation and the ability to deter further aggression. That counter-offensive is making at best marginal progress.

But long-range strike operations have their vallue. Mick Ryan says that such operations “will only grow in importance and visibility. It is a way to keep fighting when ground maneuver becomes difficult in the wet, cold season. And it is a way to project progress in the war to Ukraine’s supporters during a period of low tempo in other operations.”

Ukrainian Air Force spokesman Yuriy Inhat says Russia should expect more.

“You can see the hysteria in the Russian public, Russian propaganda channels. They really don’t like what is happening. But what did they want?” he said Friday.

Mykhailo Podolyak says the long-term goal is to inflict a wider war on Russia. “As long as Putin remains president, the war will continue. Pulling Russia deeper and deeper into the abyss of chaos.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com