New Madrid Show: A Roadmap from Cézanne to Skyscrapers

The Juan March Foundation in Madrid has a new show called “Genealogies of Art, or the History of Art as Visual Art.” They’ve done something that’s liberating, radical, and commonsensical. “In the beginning was the eye, not the word,” the show tells us, which seems obvious, but the obvious sometimes gets buried. Art historians are guiltier than most, since their raw material is visual. Connoisseurship, or even close looking, is hard sometimes. It’s easier to blabber than to look. I’m not against putting art in a social, economic, and political context, but interpretation often smothers the object. Textual narration overwhelms visual narration. I see lots of shows and read lots of catalogues. Sometimes I think of Eliza Doolittle when she sang, “Words, words, words, I’m so sick of words.”

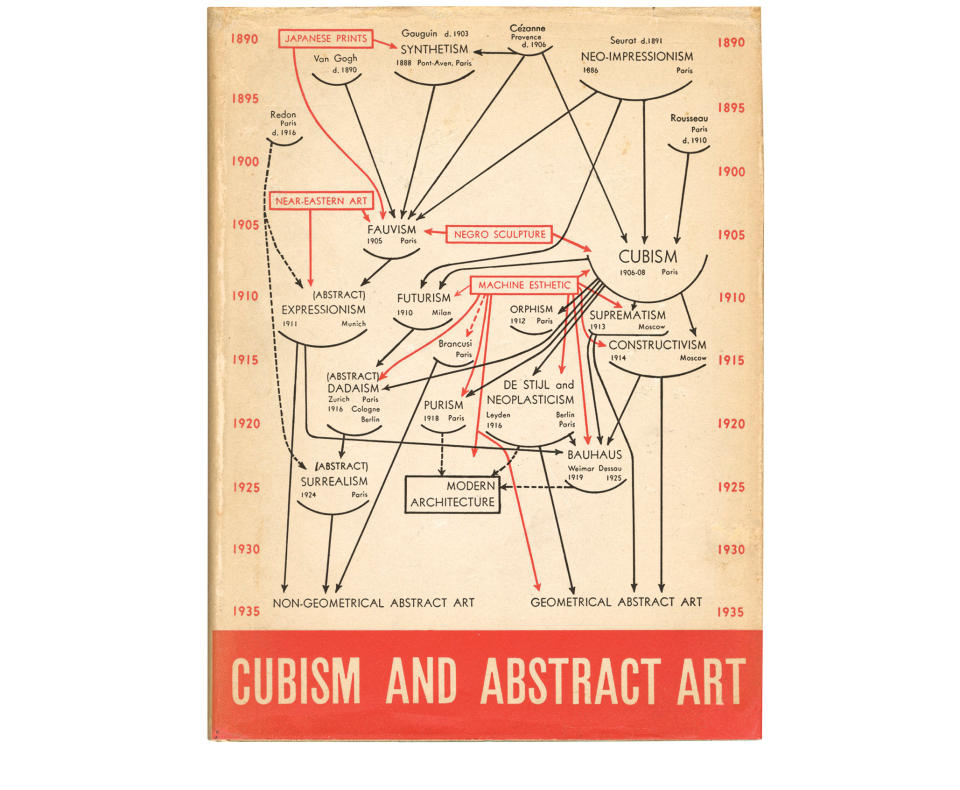

The show’s foundation is a famous diagram designed by Alfred Barr in 1936 for a show he did at the then-new Museum of Modern Art in New York on the roots of cubism and abstract art. Barr (1902–1981) was MoMA’s founding director, a museum entrepreneur, and an art historian. It’s the diagram that launched a million diagrams, and in all the charting and tracking, sometimes the art, what we see, gets forgotten. The show at the Juan March takes Barr’s two-dimensional diagram and makes it three-dimensional. It’s a brilliant show.

Alfred H. Barr Jr. En la sobrecubierta del catálogo Cubism and Abstract Art.

First, some institutional history, since the Juan March Foundation is amazing. In 1955, Juan March (1880–1962) established the place, which finances elegant art and theater spaces and exhibitions, plays, and concerts of the highest quality and often experimental. It’s free and open to the public. The exhibitions are usually focused on single artists and ignore movements, emphasizing art not widely known in Spain. I saw a great Paul Klee show years ago — his drawings — and a retrospective on Asher Durand, the anchor Hudson River School painter. Spain has little landscape tradition. Ever been to Extremadura? It’s like the surface of the moon. It’s hot and dry, flat and rocky. Nobody would paint it. American landscapes are wet and free. Madridlenos came in droves to see the show.

The Juan March is in the Salamanca District, Madrid’s Upper East Side, in a plump international-style building that looks like a spaceship. In General Franco’s Spain, in the 1950s, avant-garde culture was in a deep freeze. Culture edgier than flamenco and Velázquez was viewed as disruptive and, if not outright Red, a suspicious shade of Pink. How was the place allowed to happen?

The answer is “Juan March.” A sharp journalist in the 1930s called March “the Mediterranean’s last pirate.” Last pirate? “No es posible.” A water feature surrounded by France, Italy, Spain, Morocco, Greece, the Balkans, Libya, Egypt, and Turkey, among others, is the Ivy League campus of the School of Piracy turning out graduates every year and with a vigorous alumni association. He grew up in Majorca and made his first fortune in smuggling and his second in selling contraband to both sides in the First World War.

He was Franco’s fixer and the richest man in Spain, as well as one of the world’s first billionaires. March engineered Franco’s rise to power, in the manner of an engineer. He dealt with the nuts and bolts of the Falangist side in the Spanish Civil War. Need to move troops, but “aeroplane” are few? He found ’em. He distributed the payoff money that the Allies supplied in 1940 and 1941 to keep Spain neutral during World War II. He made money in publishing, utilities, banking, making things run smoothly. He played with others when it seemed mutually useful. Otherwise, he was invisible. And a culture giant.

March wanted a contemporary culture space in Madrid, and what March wanted, March got. The mission of the place was broadly humanistic, never poking a stick in the eye of the state but presenting eclectic, new art, theater, and music rooted in aesthetics, in sensory experience, rather than dogma. March knew there was a new world beyond Franco, and he knew it would be broadly free. He understood that aesthetics are unusually democratic because we all have the same senses but prioritize and process them individually. In his new culture space, he gave Spain a subtle push toward its post-Franco future.

A visitor to Genealogies of Art can look at the show in many ways. For me, it’s insider baseball since I was raised as an art historian through diagrams, schools, influences, and trends. Pedagogically, it’s a German obsession with putting things in classes and categories, and many of the great, early art historians were German, and many taught in American universities. Happily for me, I went to Williams College, where pedagogy was more French than German. Teaching emphasized the senses. Looking at art was an intellectual, emotional, and physical experience. Those fussy diagrams seemed porous and sometimes arbitrary, and certainly not how artists think. So I see the show as examining the divide between art and academics.

Or you can forget the diagrams, which I sometimes found bewildering and dense, and focus on the astonishing loans the museum got. The Juan March has some backup cash and immense credibility. It’s a scholarly place of the highest order. I think they channel a bit of the Old Man, too. He quietly made big things happen, by hook or by crook in his case. The curators make big things happen through formidable ambition and serious thinking.

Among the first things in the show is a gorgeous painting by Paul Cezanne, L’Allée au Jas de Bouffon, from 1890, coming from the Museum of Art and History in Geneva. All cubist roads, Barr thought, led to Cézanne, but then there’s what Barr called “Negro Sculpture,” which is African tribal art. In Barr’s day through my time as a student, Cézanne was to Picasso as Isaac was to Jacob in the Old Testament. Isaac sired Jacob, whose sons created the Twelve Tribes of Israel. Picasso launched a hundred movements based on cubism around 1912. There are magnificent things by Odilon Redon, Kandinsky, Severini, Boccioni, Gris, Léger, Braque, and Moholy-Nagy.

![<i>Femme dans un fauteuil</i> [<i>Mujer en un sillón</i>], 1929, by Pablo Picasso](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/_HVofrRnb_wAz8_HWa3ETw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTc4OQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en-US/the_national_review_738/aee9cce3dc60acc130787f3db4a80a40)

Visually, the show makes sense of Dada, Miro, Mondrian, and Bauhaus as not-so-distant cousins. It makes sense that Picasso is the thread running through the show. He was the avant-garde giant in Barr’s day. Matisse is nearly invisible. Barr found him too decorative.

There’s very little American work in the show, but that’s Barr’s sensibility. His diagram dates to 1936. Artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, and Moholy-Nagy eventually moved to America, but Barr didn’t think much of the locals. Lewis Hine is in the show, representing the “machine aesthetic,” but there’s no Stieglitz, Sheeler, Stuart Davis, and the curators, as did Barr, showed restraint and taste by excluding Georgia O’Keeffe, a good but overrated artist. The impressionists aren’t there, and neither are the Old Masters. Barr’s “Genealogies” are all about a bracing, new, modern world. There’s an American skyscraper or two in the show.

![<i>Construction (Perg 1)</i> [<i>Construcción (Perg 1)</i>], 1932, by László Moholy-Nagy.<br>Gouache sobre pergamino.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/IB.JgAFvuygQj9y3b.XP4A--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTc4OQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en-US/the_national_review_738/34e60fcbf345e6382b321f9f7eb7fd02)

Gouache sobre pergamino.

The Juan March doesn’t have an exact parallel in the United States. The Munson-Williams-Proctor in Utica is a great museum with an art school and a distinguished music program. It was intended as one-stop shopping for high culture but it’s in an abject location and has a quiet curatorial profile. The Morgan Library is close — one man’s vision, a vigorous lecture program, and small, focused shows on offbeat topics. The Clark Art Institute could be, but it’s become so tired and flaccid. Today, American museums aren’t much interested in aesthetics or ideas, anyway. Delegations of American curators should go to the Juan March to learn how to be less boring.