How the mafia operates in France's Corsica, out of tourists' sight

With its rugged coastline and pristine natural beauty, Corsica is a jewel in the Mediterranean Sea.

The French island, just a stone's throw north of Italy's Sardinia, attracts millions of tourists each year, but only very few of them ever become aware that the mafia is holding Corsica in its ironclad grip.

For the locals, threats, hush money payments and fudged construction work are part of daily reality. It's also not rare for people to be killed by the mafia.

Often dubbed "the island of beauty," Corsica is the region in France, excluding its overseas territories, with the highest murder rate in relation to the number of inhabitants.

Last year, the island recorded 3.7 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, with many of the killings perpetrated by the mafia, according to the Interior Ministry.

"The worst thing is that these cases are not solved because there are no witness statements," says anti-mafia activist Josette Dall'Ava-Santucci. She attributes this phenomenon to the "omertà," a code of silence also imposed by mafia gangs in southern Italy that requires non-cooperation with the authorities.

It was long disputed whether there even is a mafia operating on the Mediterranean island. According to prosecutor Nicolas Bessone, who is responsible for organized crime in Corsica, that question is no longer relevant. "I think we need to be clear," he recently told the France Bleu channel: mafia organizations exist in Corsica.

According to an internal report by an anti-mafia unit of the police and gendarmerie, quoted by French media, 25 criminal gangs are active on the island.

The mafia first became active in Corsica in the 1980s, Dall'Ava-Santucci says, when investment plans were being drawn up for the mountainous island.

Today, criminal gangs have infiltrated the lucrative construction industry and the real estate business and control drugs trafficking, says Dall'Ava-Santucci, a 82-year-old doctor who founded the anti-mafia organization Maffia Nò with fellow campaigners in 2019.

It is hard to say how big Corsica's mafia gangs are, as many of their activities take place out of sight, she says.

Dall'Ava-Santucci estimates that each of the 20 or so gangs may have a dozen members. While that doesn't sound much, it adds up to a significant number considering that Corsica only has 350,000 inhabitants.

On top of that are those in the judiciary and tax authorities, the prison system and occasionally even in the police who have been bribed by the mafia, she says.

Prosecutor Bessone suspects that the mafia also has links to politics.

According to Jean-Jacques Fagni, a lawyer at the court of appeal in the northern town of Bastia, the gangs don't operate in distinct territories. Both he and Bessone say that different criminal organizations sometimes even cooperate across the island.

Dall'Ava-Santucci has spoken to many of the Corsican mafia's victims. In some cases, the criminals took people's doors when they hadn't paid rent on time. In other cases, they attempted to take their entire homes. Warehouses and work equipment owned by rival companies were blown up and building permits extorted. The gangs also manage to push down property prices.

"A whole generation knows the mafia as employees or as company managers," she says.

The gangs drive up the costs of public works, carry them out sloppily and sometimes manage companies though they lack the ability to do so, she adds.

Meanwhile, the roughly 3 million tourists visiting Corsica every year don't notice a thing, according to Dall'Ava-Santucci.

On the contrary, the island is very safe and there are rarely any robberies or other reasons to be afraid to walk alone at night, she says.

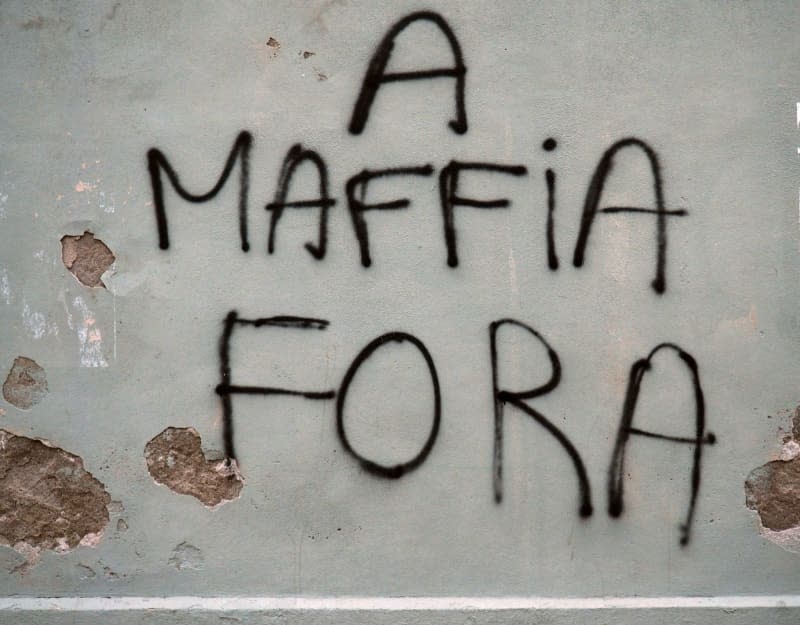

A tourist would not notice whether their holiday rental or a bar is owned by the mafia. The only visible sign of the clandestine criminal structures tormenting the island is graffiti calling for "Mafia out" on some of Bastia's streets.

In the fight against the gangs, Dall'Ava-Santucci is looking to mobilize residents, lawmakers and the authorities alike. Specifically, she is calling for more police, a separate criminal offence to be introduced for mafia-related crime and lay judges at the jury court to be replaced by trained professionals. She also says goods suspected of being controlled by gangs should be confiscated immediately and any bans on people who should not be allowed to manage businesses to be extended.

Tougher prison sentences, on the other hand, won't help to improve the situation, she says. "Prison is where the mafia organizes itself. They do what they want in prison."