Major changes are coming for USC’s Williams-Brice Stadium. Here’s what to expect

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The buzz around Williams-Brice Stadium on a football game day is palpable. It’s busy, noisy and awash in foot traffic.

A summer night, however, is quite different.

On this Friday night in late June, Key Road is mostly quiet. The activity along George Rogers Boulevard is limited to a few families taking their dogs on evening walks. Meanwhile, Bluff Road offers its familiar symphony of vehicles buzzing up and down the four-lane street.

But if university leaders’ vision comes to fruition, the streets and property near USC’s football stadium will be Columbia’s newest hub for retail and entertainment that stands to pump millions of dollars into what USC says will be a “major modernization” of Williams-Brice Stadium.

The reasons why South Carolina would turn to outside developers and their private funding to improve Williams-Brice Stadium make sense when you consider trends in fan interests and venue renovations, and the pros and cons of how such projects are typically financed.

For the fans in the stands as soon as a few years from now, the look, feel and experience won’t be the same. Exactly what changes are coming to South Carolina’s almost 90-year-old stadium — and how soon — remain to be seen, but national trends offer hints as to what could come to the home of the Gamecocks.

“There are opportunities in the entire stadium,” Wayne Hiott, chief executive officer for the Gamecock Club, told The State.

Expect Williams-Brice to keep its signature look

Because USC is a public entity and this undertaking goes through a state approval process, school leaders aren’t yet able to divulge many specifics beyond speaking generally about possible stadium improvements and what the outside development additions might include.

Still, two nuggets from the February press release that announced the stadium project answered one big-picture question and teased at least one larger factor for curious fans to consider:

▪ “The project will not include moving Williams-Brice Stadium from its current location or acquiring and developing the state fairgrounds.”

That point debunked months of rumors that USC was going to buy the adjacent fairgrounds.

▪ “No disruption to future home game schedules is anticipated.”

This statement seems to acknowledge that stadium renovations could be significant, and construction timelines in the post-COVID years have been as unpredictable as ever. A full-stadium demolition is not expected, senior university leaders have said.

“There’s certainly a desire for us to keep the look, the iconic look, the same,” Hiott said. “And that means keeping the same bones.”

The first public domino regarding the impending stadium project fell Feb. 7 when USC revealed — after almost two years of behind-the-scenes discussion — that it was issuing a formal Request for Information, or RFI. In the simplest terms, an RFI is just that: USC was seeking information or input from interested developers on what (i.e., restaurants, housing, office space, etc.) could be built on the university-owned land.

USC last issued an update on the RFI phase on April 14. A statement from a university spokesman said “the university received inquiries from more than two dozen companies, and we received written responses from several development groups with experience executing major multi-phase projects. ... We are now focused on refining a scope of work and adding definition to the project.”

The school in the coming weeks is expected to make another announcement as it transitions to the Request for Qualifications phase (RFQ), where South Carolina would ask a group of developers to submit their expertise for fulfilling such a large development project outside of Williams-Brice Stadium. USC leaders can offer input about what they’re hoping to achieve.

The process ends with a Request for Proposal (RFP), where USC would ask for bids from a defined group of developers.

The final outcome? USC would enter land-lease agreements with a company or companies that develop the school-owned property, a process that could come in the form of a master development agreement and generate “significant private funding” that would go toward stadium improvements. The school would first look to develop land near the football stadium, then follow that up with a second phase around Colonial Life Arena.

The long-term plans outside of Williams-Brice will likely draw inspiration from a place such as The Battery Atlanta — the vibrant area of restaurants, hotels, office centers and more that are adjacent to the Braves’ new MLB ballpark.

“We have an asset, which is land. It’s valuable,” athletic director Ray Tanner told The State. “There are not many football stadiums in this country, including the NFL, that have space to do things we can.”

The available land from USC for such development, the school said, includes “areas adjacent to and including the existing footprint of Williams-Brice Stadium as well as more than 800 acres of undeveloped property” behind the football operations building.

Asked in February when any construction might begin, Tanner estimated at least 12 to 15 months for working through various layers of state approval processes. USC started with a “blank canvas,” Tanner said.

As the process moves along, more gets added to that canvas.

“We don’t know what’s going to end up there,” Tanner said. “But we’re trying to engage people more than seven Saturdays a year. Everyone asks if a golf course is coming. We haven’t gotten that far down the road yet. It would be a great location for it. …

“We’ve got the corridor of Bluff and Shop (roads). So many students living over there are going to the Vista and Five Points now. If we’re successful in our project at Williams-Brice, that might be their destination, if there are areas of entertainment or restaurants.”

Planning for significant changes to Williams-Brice Stadium before the 2024 season would be optimistic — 2025 and beyond might be a more likely time frame, based on how other colleges have been able to complete major projects.

Expect the external look of the stadium to retain a similar look, Tanner said.

“That’s an impressive stadium,” Tanner said. “It’s been there a long time. I like our stadium. I like Williams-Brice.”

Expect premium seating to be a priority

It’s a virtual guarantee any upgrades inside Williams-Brice Stadium will include the addition of luxury or executive suites.

South Carolina has 18 such suites, which puts the Gamecocks at or near the bottom of the SEC. By comparison:

▪ Georgia has 86 (including 11 at field level).

▪ Florida has 80.

▪ Kentucky has 67 (20 in each end zone and 27 on the sidelines).

In-state rival Clemson has 95 suites. SEC foe Texas A&M added 23 more this offseason for a whopping total of 140 suites.

“It’s paramount” to have suites, said Andrew Elmer, regional leader for sports, recreation and entertainment for the HOK design and architecture firm. “It’s the No. 1 revenue driver for these facilities. You can charge so much more for a premium seat.”

Per Hiott, USC has a waiting list 118 names to buy a suite. Almost all of those on the list are individuals or families.

A suite currently costs $87,000 in the first year of a three-year commitment. The price escalates from there. Just doubling the number of suites to 36 would add $1.57 million in annual revenue that first year. Imagine if USC could build as many suites as the aforementioned colleges.

“It pays for itself in a relatively short amount of time,” Hiott said. “If you can accommodate the demand and it can pay for itself relatively quickly, it’s a no-brainer.”

In the current setup, the 18 suites at Williams-Brice are same size and include:

▪ 24 tickets per game;

▪ two rows each with six black leather seats as well as barstools;

▪ six access passes to give to friends so they can get in the suite;

▪ two parking spaces.

A suite does not include food or catering, but owners can stock it with alcohol and beverages.

All 18 of USC’s existing suites span the width of the west side of the stadium (closest to Bluff Road and facing away from the setting sun). The most logical place to add more suites would be to start with the matching locations on the east side. The school would most likely add suites there first before considering other areas of the stadium (such as field level).

Expect changes that impact all fans

USC leaders say all fans will be impacted by the upcoming changes to Williams-Brice.

In the current setup, slightly more than 14% of all seats in Williams-Brice have access to air conditioning (via a suite or club space), a number that’s sure to grow when the stadium is upgraded.

“That’s low, especially in a Southern climate,” Elmer said. “Air condition and shade are very important.”

So what improves for the average fans who only have access to common areas and their seating?

“This concerns the average fan as well,” Tanner told reporters in February. “We’re not turning the entire stadium into premium seating, but we may have the opportunity to enhance the general seating.”

A logical change could be converting the stadium’s bleacher seating to individual chairback seating. USC has not said whether or not such a change will be considered, but chairback seating is a staple at pro stadiums. The Gamecocks’ Colonial Life Arena basketball venue and Founders Park baseball stadium have individual chairback seating.

Either way, expect USC to spruce up its seating variety.

“Nobody wants to sit in a bleacher seat for four quarters. Some of these football games go for three and a half to four hours,” Elmer said. “The modern fan does not want to sit on a bleacher or even a chairback seat for an entire football game. The modern fan wants a diverse array of experiences within and around the stadium.”

There is a desire for to-be-determined enhancements for students and the student section, Tanner told The State.

“The younger demographic wants to be up and moving around,” Elmer said.

It’s also fair to expect the university to continue to upgrade restrooms, concourses and food options, and to improve fan flow in, out and throughout the stadium.

Some other modern amenities a college might consider for its upgrades, according to Elmer, are:

▪ Concourses and concession areas that have visibility to the playing field;

▪ Grab-and-go concessions, similar to airports and some pro stadiums;

▪ Stadium-wide WiFi;

▪ An open-air beer garden with a view of the game that’s accessible for general ticket fans but with a season-long cost for access. Wisconsin added such a space called the Touchdown Club with its latest stadium upgrades.

Colleges that are embarking on major stadium renovations, USC included, often cite improving the “fan experience” as a central goal in their projects.

“ ‘Fan experience’ is the easy way of saying, ‘We want the fans to come to the game, stay at the game and enjoy it while they’re there,’ ” Elmer said.

A lot of the changes in and out of Williams-Brice Stadium over the past decade have been done with all fans in mind: a new video board, the Springs Brooks Plaza, a stadium light show, in-venue video production, the Gamecock Walk, etc.

South Carolina’s main video board is 11 years old and could also receive some upgrades.

Expect meaningful changes that affect USC’s football team, too, such as a new locker room and improvements to players’ walking spaces to and from the field.

Expect a reduction in capacity

Once upon a time, Williams-Brice seemed destined for expansion to where capacity would push 90,000.

In 2006, South Carolina was actively pursuing design work that would lift the stadium from 80,250 to 87,000 or 88,000.

“If we can sell the tickets, certainly it’s needed,” Steve Spurrier said before a May 2006 Gamecock Club meeting ahead of his second season as the program’s head coach.

Times changed. Trends changed. Bigger is no longer better when it comes to sports facilities.

“It’s evident to me that no matter if you’re talking about football, baseball, basketball, collegiate or professional ranks, they’re building premium experiences for fans with fewer seats,” Tanner said.

Some of the NFL’s newest stadiums are at or below a capacity of 70,000: Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta (71,000), home to the Falcons; SoFi Stadium (70,000) in Inglewood, California, where the L.A. Rams and L.A. Chargers play; and Allegiant Stadium (65,000) in Paradise, Nevada, home of the Las Vegas Raiders. The new proposed stadium for the Jacksonville Jaguars has a base capacity of 62,000. The Buffalo Bills’ new stadium is projected to have between 60,000 and 63,000 seats.

“I don’t know that we want to go that low, but when we grow with premium, we’re not going to lose a lot of seats,” Tanner said. “But we could lose some and I think it would be OK.”

This isn’t to say changing capacity is a motivating factor behind USC’s vision. Still, it’s fair to expect the upcoming stadium work to result in a tick downward in total seats, even if it’s not a big change. A move to individual chairback seating would certainly bring capacity down.

“We’re not having clients in the college market coming to us and saying, ‘We want to add seats,’ ” Elmer said.

Williams-Brice capacity was 80,250 through the 2019 season, dropping to 77,559 with renovations that added loge box seating and new club spaces for the 2020 season. And though USC promoted ticket sellouts with six of its 2022 home games, actual average attendance was typically at or near 60,000.

It’s still easy to stay home and watch the games from the comfort of a living room, a not-new trend that was exacerbated by the COVID pandemic’s attendance restrictions. And modern technology makes every game available for viewing at home or on the go.

The upcoming stadium project is expected to add amenities that mimic what a fan might have at home while elevating the experience that can only be felt in person.

Said Hiott: “We’re transitioning into things that improve game-day experience for our fans and our student-athletes, which really means removing the barriers to coming to a football game to where you can’t experience a game day at Williams-Brice or anything close to it anywhere else.”

Expect stadium funding to look different

South Carolina has spent upward of $152 million since 2012 on football facility upgrades alone, the biggest investment coming with the $50 million operations building that opened ahead of the 2019 season.

Such projects are typically funded from a combination of sources: capital fund-raising campaigns and donors; USC’s own financial reserves; and through borrowing money.

“Our revenues are not at the top of the Southeastern Conference,” Tanner said. “We’re very grateful for our donor base, our Gamecock Club members and what we do have. But there are schools in our league that have a lot more revenue to do some things they’d like to do. We work hard at it. What we do have is in a good place.”

South Carolina ranked 10th among the SEC’s 13 public schools in annual athletics revenue for 2022, according to USA Today’s database of college finances. That ranking becomes 12th of 15 if you factor in new conference additions Texas and Oklahoma. The current SEC schools stack up this way financially:

Alabama $214 million

Georgia $203 million

LSU $199 million

Texas A&M $193 million

Florida $190 million

Auburn $175 million

Kentucky $159 million

Tennessee $155 million

Arkansas $152 million

South Carolina $142 million

Missouri $141 million

Mississippi $134 million

Mississippi State $111 million

Funding stadium improvements through giving alone is hard; and borrowing has its limits — literally. USC’s athletics department has a “debt ceiling” of $200 million that it can borrow against. The available amount fluctuates as USC pays down that debt.

South Carolina’s athletics department makes money now from ticket sales, multimedia rights, major donor giving, the Gamecock Club, the SEC’s revenue distribution and through the apparel deal with Under Armour.

The thought process is that the new development near Williams-Brice Stadium and Colonial Life Arena will provide a new and lucrative revenue stream — university leaders have said it could produce $1 billion revenue over time — that’s used for stadium improvements. That’s an enticing new option vs. spending, say, $20 million every few years through borrowing and fund-raising just to upgrade a few elements of the stadium.

Whatever changes come to Williams-Brice are likely to still be funded by a combination of the new revenue stream plus traditional borrowing and a fundraising campaign. That new money, in theory, gives USC greater flexibility to do more — and do it in a shorter period of time.

There’s also the emerging reality that donor money is being given nowadays to name, image and likeness collectives to raise the university’s impact in that NIL space. The trade-off? That’s often money that was being given to USC for other causes such as athletic projects.

“Donors have a choice,” Tanner said. “They can give to a collective or they can continue to give to the university, the athletic department, projects or campaigns. They have to make a decision. That’s where we are NIL.”

Expect the upgrades to represent a major financial investment

South Carolina hasn’t offered an estimate yet for how much stadium improvements might cost, but it’s likely to be well over $100 million — a figure that would be the highest single investment USC has made in a facility.

Colonial Life Arena cost $64 million when it opened in 2002. Founders Park opened in 2009 with a price tag above $35 million. The football operations building cost $50 million.

At Williams-Brice, a full west side replacement and upper deck addition in 1971 and ‘72 cost $6.9 million, with an east side upper deck addition in 1982 costing $10.2 million. (Adjusted for inflation, those renovations are closer to $50 million each.)

The recent and current costs for other major football stadium renovations nationally range from low $100 millions all the way to the Jacksonville Jaguars’ proposed new stadium that will cost $1 billion.

Some colleges are opting to replace an entire side of their stadiums in one offseason. Texas A&M and Oregon State have done that, while Ole Miss and Penn State are making plans to do the same — the cost of the Nittany Lions’ plans is projected at $700 million. Vanderbilt, meanwhile, will play the entire 2023 season without seats in the end zone as construction continues in their $300 million project. San Diego State and Colorado State have opted for brand new stadiums in recent years.

A full-side replacement for other colleges typically means a brand-new west side of a stadium, as that’s most often where the more desirable seats are away from the afternoon sun — and where it’s more lucrative to add luxury suites.

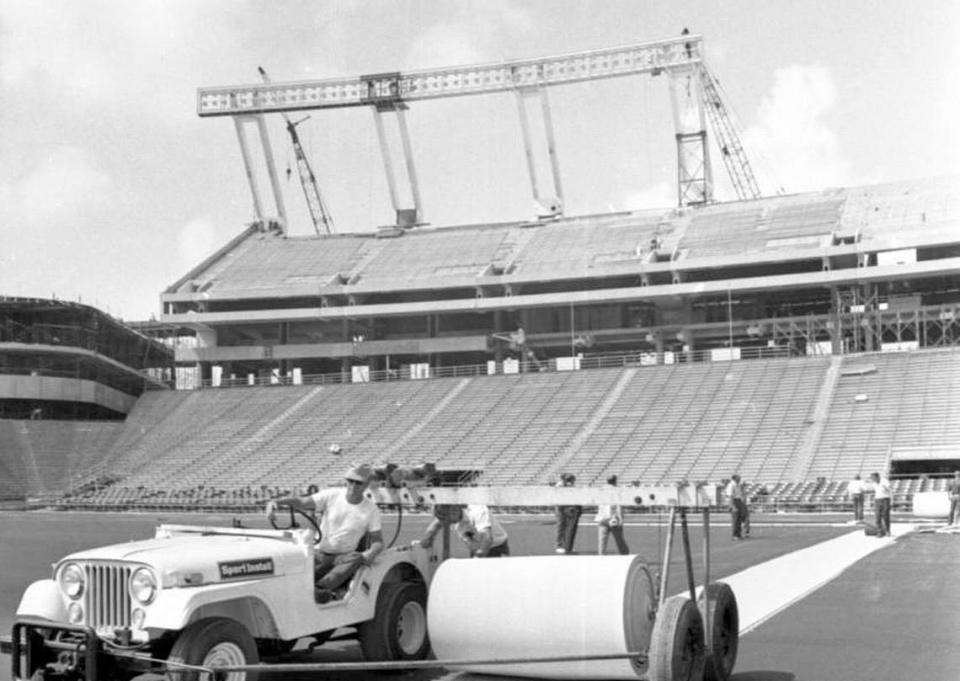

However, in the years since Williams-Brice replaced its entire west side, millions of dollars have been spent on suite upgrades, new elevators, club spaces, a new press box and concourse improvements.

It’s the east side that’s devoid of suites, with some lower bowl seating original to USC’s football stadium. An upper deck was added in 1982 and had to be reinforced when fans noticed it would vibrate and move. (It’s what helped coin the USC catchphrase, “If it ain’t swaying, we ain’t playing.”)

USC hasn’t said that either side of Williams-Brice will be demolished and rebuilt, but the east side appears to offer the most potential for major changes. The north end zone (where students currently sit) is also an area that could be enhanced, with the latest work there being the new video board addition in 2012.

Expect South Carolina to invest in change with the goals of making money while elevating fans’ experience in and around Williams-Brice Stadium.

“The universities want to generate revenue,” Elmer said. “They want to create unique fan experiences that support their traditions and embody their culture. Everyone is unique and there’s a way to translate that architecturally.”

College football stadium projects

A look around the country offers examples of the possible spending that will be involved with USC’s project:

▪ Tennessee’s $340 million stadium project started in 2017 and is ongoing. Additions include new suites, club space, improved restrooms and concession areas, and stadium-wide Wi-Fi, among other things.

▪ Vanderbilt says its $300 million project goes toward, among other things, major changes to the football and baseball stadiums. The FirstBank Stadium upgrades include a new videoboard and sound system, a full replacement of seating in one end zone, a new football game-day locker room. Vandy is also adding an indoor football practice facility. Vandy’s new premium options include “living room boxes, loge boxes, club seating, field-level seating, founders’ suites, club suites and open-air tailgate suites.”

▪ Penn State plans to spend $700 million to renovate Beaver Stadium, with construction starting in January 2025 and wrapping up before the 2027 football season. Changes include full renovation of one side of the stadium, new bathrooms, better concessions and “much-needed premium seating.”

▪ Ole Miss says its $215 million plans for Vaught Hemingway Stadium include a full replacement of the west side of the stadium.

▪ Oregon State’s $153 million stadium project started in 2021 and is supposed to be done in time for the 2023 season. The work there includes demolishing and fully renovating one side of the stadium.

▪ Oklahoma State is spending $55 million over a few years to upgrade its seating.

Williams-Brice Stadium history

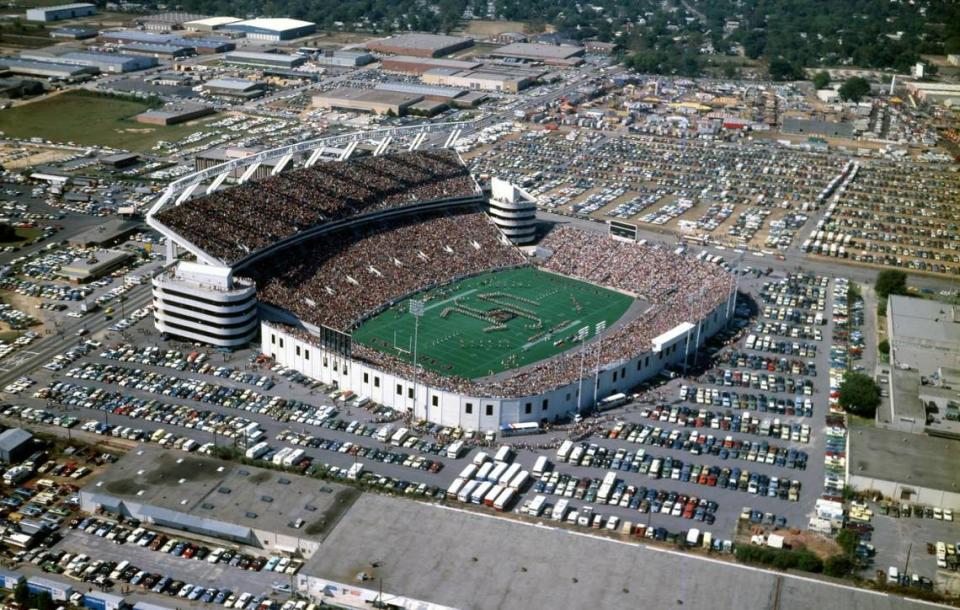

1930s: The stadium as originally built opened in 1934 and included 17,500 seats with $82,000 of funding, according to published reports. It was known as Columbia Municipal Stadium and became Carolina Stadium in 1941.

1960s: Stadium growth brings capacity to around 43,000.

1971-1972: Entire west side of stadium is replaced, including a new lower grandstand and the addition of an upper deck that cost $6.9 million and raised capacity to 56,400 seats. The name was officially changed to Williams-Brice Stadium.

1982: An upper deck was added above the existing east side stands, raising capacity to 72,000. Work cost $10.2 million.

1995: $9.9 million went toward west side luxury suites, club seats and a new press box.

1996: $13.5 million spent on south end zone project, 8,000 seats added. Capacity raised to 80,250.

2005: $3 million for Crews Building/weight room and meeting rooms on south side of stadium.

2012: $6.5 million videoboard added to north end zone.

2012: Gamecock Park tailgating area opens beside Williams-Brice at a cost of $30.5 million ($15 million for the site and $15.5 million for construction/landscaping).

2015: $14.5 million Springs Brooks Plaza opens surrounding the stadium.

2020: $22.5 million spent on club spaces additions and renovations. Capacity down to 77,559.

2022: $11 million for new stadium lights, sound upgrades, new west side elevators.