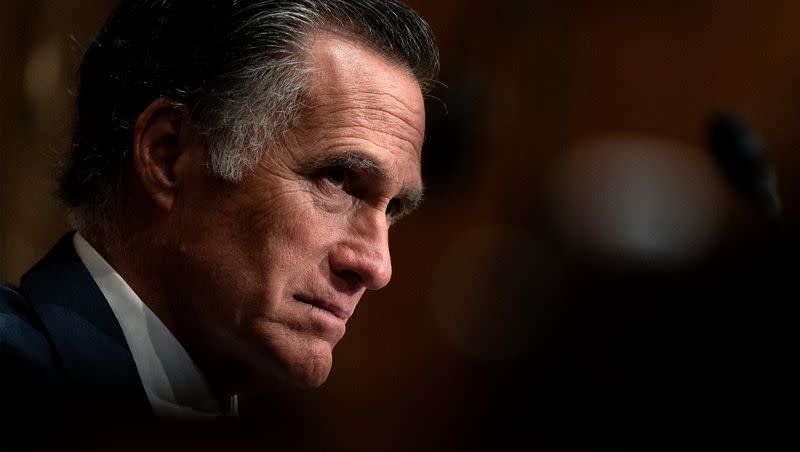

The making of Mitt Romney

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor’s note: The house style of Deseret Magazine is to refer to members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints by the name of the church. The book, as excerpted here and in Deseret Magazine’s November issue, refers to members of the church as Mormons.

Every family has its own mythology, the stories they choose to tell about themselves. The Romneys’ stories tend to be about stubbornness.

There was George, who delivered a belligerent speech at the 1964 Republican convention opposing his party’s nomination of Barry Goldwater. There was Gaskell, who sued the Mexican government — and won — after losing his home during the revolution, and Rey, who flouted laws against foreign proselytizing and turned up in Chihuahua passing out Spanish copies of the Book of Mormon.

This story began with Miles Romney, a 19th-century British carpenter who, upon hearing Mormon missionaries preach in a town square, renounced the Church of England, converted to Mormonism, crossed the Atlantic and walked across the American Plains to join his fellow Saints in building their desert Zion.

Related

Charged with designing a tabernacle in the southern Utah settlement of St. George, Miles became fixated on erecting a grand spiral staircase that would lead up to the second-story dais. When the Mormon prophet, Brigham Young, saw the plans, he concluded that the podium would be too high and instructed Miles to cut down the staircase. Miles balked. The prophet insisted. A standoff ensued, and nearly 200 years later the St. George Tabernacle — with its grand spiral staircase that rises majestically to the building’s second story before awkwardly descending 10 feet to the dais — stands as a testament to the lengths a Romney man will go when he believes he is right about something.

Romneys were not descended like other humans, the family saying goes. We descended from the mule.

It was not at first clear that Mitt Romney had inherited his forefathers’ stubbornness. As a kid, he didn’t seem to hold many strong convictions at all. Skinny and good-looking, with an impish sense of humor, he glided through grade school charming and exasperating his teachers.

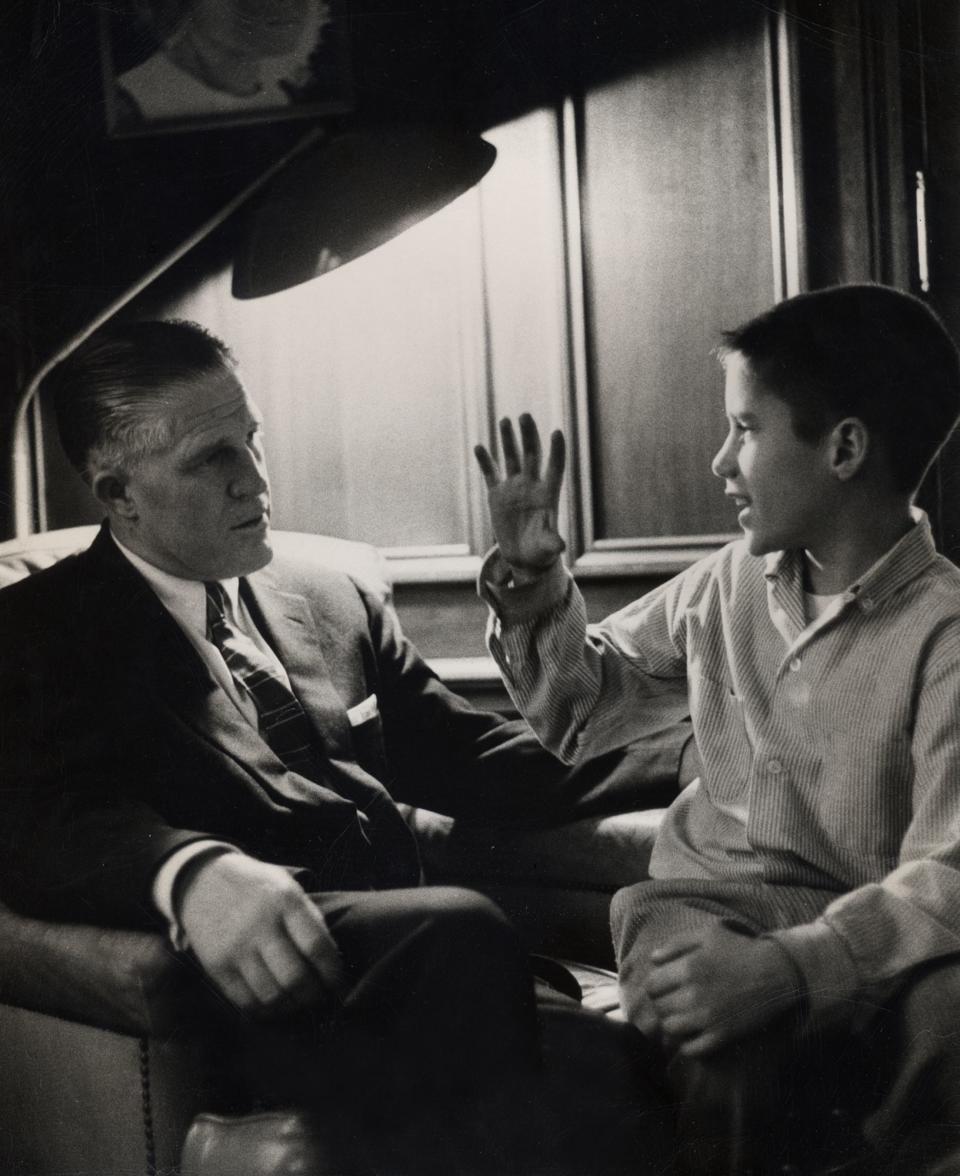

His parents had high hopes for their precocious youngest son. They saw his potential, and in some ways, they saw themselves in him. His father George delighted in arguing with Mitt, their debates often dominating the family dinner table until both were laughing and gasping for breath. On road trips, his mother Lenore read aloud from the poetry of Sam Walter Foss — “Bring me men to match my mountains” and Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King.” But the calls to greatness fell flat. Mitt loved his parents, but he felt little drive to rise to their expectations.

When he was 12, he entered Cranbrook, the private boarding school to which Michigan’s ruling class sent its children, and quickly learned that he wouldn’t make it as a jock. The football team cut him at tryouts, and he spent his brief wrestling career getting his limbs bent in ways they were not meant to bend by boys much stronger than he was. Even track, that last refuge of the unathletic teenager, was ruled out after he discovered by way of the presidential fitness exam that he ran the slowest 50-yard dash in his class. He spent time in the yearbook office and the glee club, and one year his mother even urged him — as a kind of Mormon rumspringa — to join the “smoking club.”

“If he wants to smoke,” she insisted, “he can smoke.” Mitt did not want to smoke, but he enrolled in the club anyway to appease his mom and never attended a meeting.

His true extracurricular passion was pranks. At Cranbrook, he was the kid who filled dorm rooms with shaving cream and blared obnoxious ooga horns during slow dances. He liked to dress up as a firefighter and run into stores pulling a hose and shouting, “This place is gonna blow!” After acquiring a siren and some blue lighting gels from the campus auditorium, he drove around town posing as a police officer and “pulling over” his friends. He carried himself with a rich-kid carelessness — the untroubled air of someone who knew he could get away with anything.

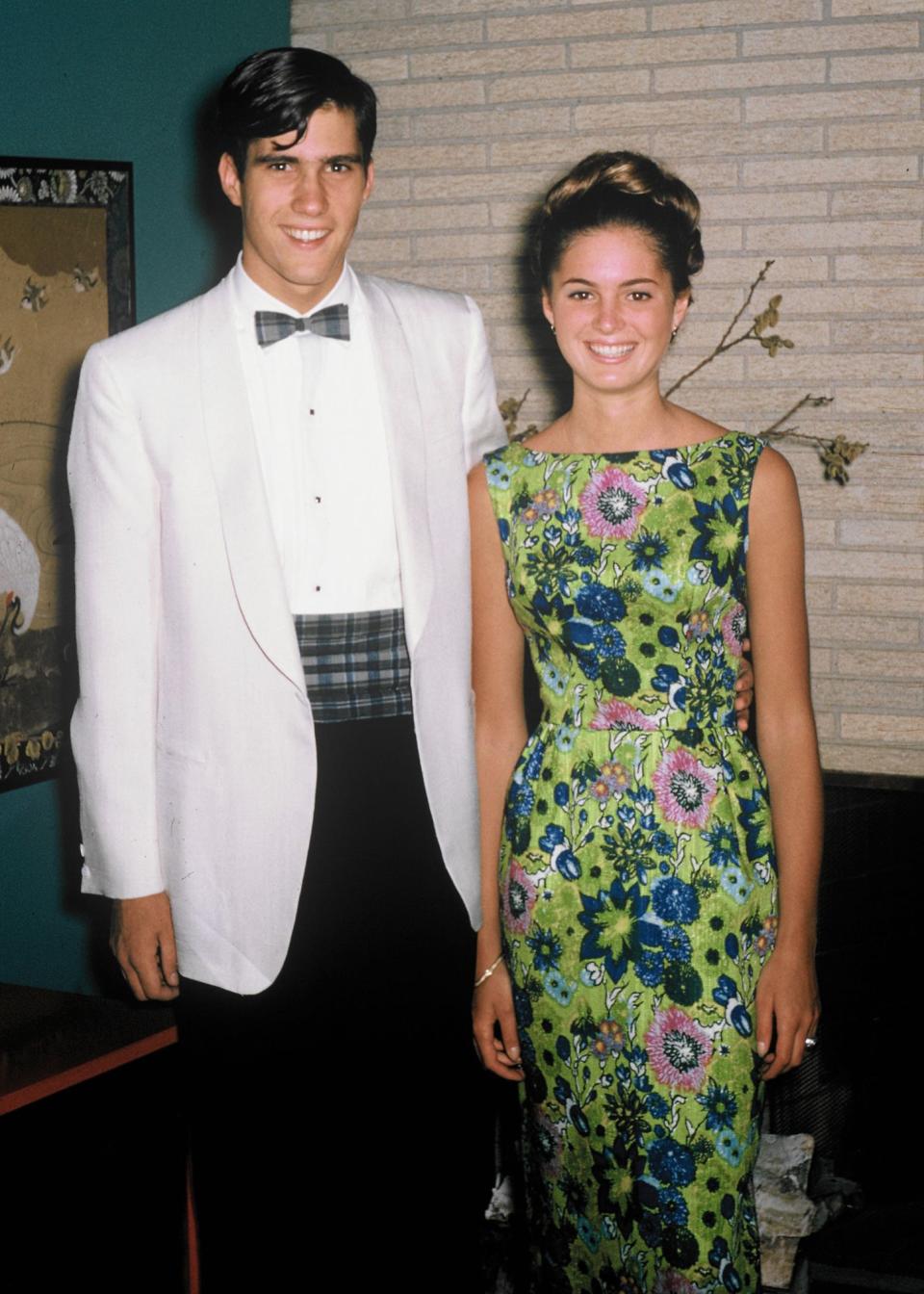

Then he met Ann Davies. He saw her for the first time at a party. She was beautiful and wholesome and slightly reserved in a way that intrigued him, not bubbly and loud like other girls. She was also 15, a sophomore at Cranbrook’s sister school, which suggested to Mitt that she’d be easy to impress. For their first date, he took her out to dinner at the Detroit Athletic Club, where his dad was a member, and then to a screening of “The Sound of Music.” More dates followed, as well as regular nightly phone calls between dorms, but as Mitt became more infatuated she remained standoffish.

Shortly after they began dating, Mitt had to spend a few days in the hospital with appendicitis, during which time, he learned, Ann went on a date with another boy. When Mitt confronted her, expecting a sheepish apology, Ann was defiant. “Do you think you own me or something?” she demanded. “I’ve gone out with you a few times, that means I can’t go out with someone else? I’m supposed to clear that with you?” Mitt was in love.

Ann eventually fell in love, too, but she had other things on her mind. One night, after a date, Mitt parked on a quiet hill near his family’s house and leaned in to kiss her. She stopped him with a decidedly unsexy question: “What do Mormons believe?”

This was not a subject he was interested in discussing right at that moment, but he dutifully searched his mind for an answer. He recited the church’s first Article of Faith: “We believe in God, the Eternal Father, and in His Son Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Ghost.” To Mitt’s alarm, this led to a theological conversation about the nature of God. The subject had been bothering Ann ever since her Episcopal priest suggested to her that he didn’t believe in a divine being so much as a general presence of good in the world — an abstract notion that had left Ann cold and searching. Now, as she listened to Mitt describe his church’s teaching that God is a person, a literal heavenly father who knows and cares about each of his children, she was overwhelmed with emotion and began to cry. With the prospect of romance now fully evaporated, Mitt spent the rest of the evening reciting other passages of Mormon scripture to his intensely fascinated girlfriend.

Mitt took Ann to prom later that year and told her that he wanted to marry her one day. She said she felt the same way. But when he suggested that he might skip his Mormon mission so that they could start their lives together sooner, she balked. Somehow, she knew better than he did how important his faith would become to him.

“You’ll resent me for the rest of your life,” she told him. “You have to go.”

His Mormon faith no longer felt to him like just a part of his heritage, an interesting heirloom passed down by his fathers. It was expanding, gaining texture, attaching itself to every part of him.

When the time came, he submitted his papers and prayed for a mission assignment to Great Britain, where his father and great-grandfather had served. George even called in a favor with a friend on the church’s missionary committee, who said he would do his best. But when Elder Thomas S. Monson, an apostle in the church, reviewed the list of missionary assignments, he stopped at Romney’s name and said, “That’s the wrong mission. He’s supposed to go to France.”

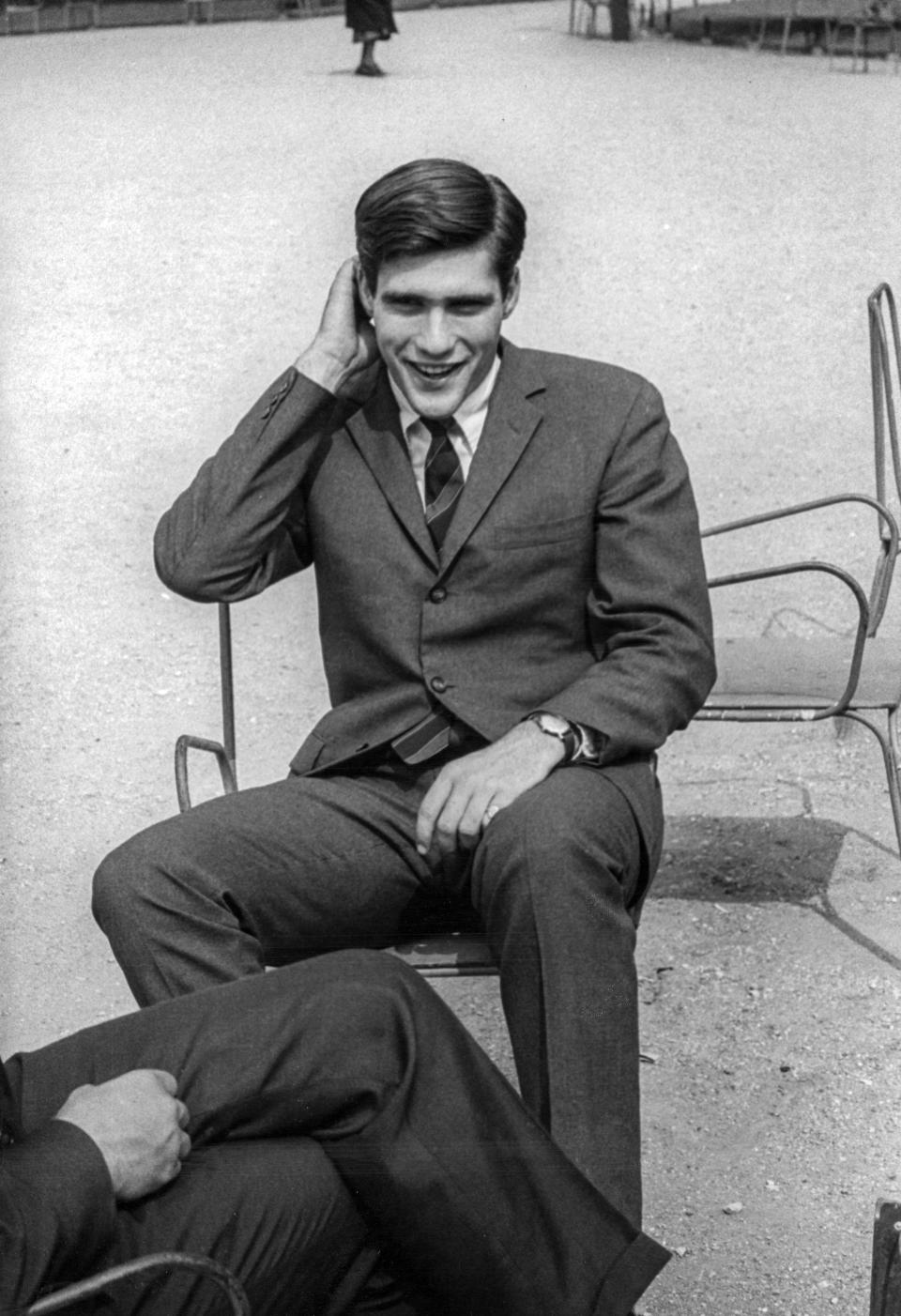

Mitt arrived in the country a few months later, and was assigned to serve in Le Havre, a working-class port city in Normandy that was still recovering from its decimation during the war two decades earlier. The city had a haunted quality to it; according to mission lore, the last missionaries sent to Le Havre were never heard from again.

Romney and three other missionaries took rooms in a hotel across the street from the train station that they would only later learn to be a brothel and went to work. Rising early each morning and mounting their Mobylettes, they scoured the city for people who were willing to listen to young American men share a message about Jesus Christ in broken French. It was a tough sell. Le Havre was predominantly communist, and the residents’ default skepticism of religion was compounded by their dislike of Americans, whom they blamed for the bombardment that leveled their city in World War II.

Every day, Romney and his fellow missionaries would pick one of the brutalist concrete towers in town, climb the stairs to the top, and spend hours trudging through the halls, knocking on doors one by one and getting them slammed in their faces: “I don’t want any” — BANG — “Get out of Vietnam” — BANG — “No, no, no” — BANG.

Entire months would pass like this, without a single person inviting them in to talk. Their shoes wore out; their feet blistered. The Sabbath offered little respite from the rejection — because there were no Mormons in Le Havre, there was no church to attend on Sundays and their meager budgets meant that they could usually afford to eat just two meals a day.

For Romney, the governor’s son, the prep school prankster, this was something altogether new. The day-in-day-out grind, the punishing schedule — it was worse than difficult; it felt pointless. “Why are we doing this?” he repeatedly asked the other missionaries. “We’re accomplishing nothing.” Back home, he had friends and school and a future and a girlfriend with whom he was madly in love. Here, he just had those concrete towers with their endless flights of stairs and their ever-slamming doors.

Making matters worse, Romney had developed a persistent case of diarrhea shortly after arriving in Le Havre. The condition left him weak and dehydrated, when he wasn’t scrambling for a toilet, and no matter what he did, he couldn’t seem to find a cure. The low point came one day when he and his companion were talking to a family they’d just met in a courtyard. Suddenly feeling as though he might faint, Romney hobbled out to the street, collapsed into a gutter, and soiled himself.

It was around this time that Elder Romney received a book from his parents in the mail, “The Autobiography of Parley Parker Pratt.” A distant ancestor on his father’s side, Pratt was one of Mormonism’s legendary early missionaries, having baptized hundreds of people as he preached the gospel throughout North America. Reading the book one night in his run-down room in Le Havre, Romney came across a story about Pratt’s own early struggles as a missionary. Pratt had spent months laboring in New York City without converting a single soul. Then, one day, he kneeled to pray with his companions and received a miraculous vision. “The Lord said that he had heard our prayers, beheld our labors, diligence, and long suffering towards that city and that he had seen our tears,” Pratt wrote. “Our prayers were heard, and our labors and sacrifices were accepted.”

Romney’s room did not fill with light when he read the passage; he did not receive a vision. But it struck him with the force of something divine. Our sacrifices were accepted. This was the point of his mission, he now realized — doing the hard thing, making the sacrifice. Maybe it would yield fruit, maybe it wouldn’t. But the difficulty and deprivation would have their own sanctifying effect, and that was reason enough to keep trying.

Romney’s mission didn’t necessarily get easier after that. In Nantes, a group of drunk rugby players dragged him into a brawl and he wound up in a police station; in Villemomble, he was arrested again for “impersonating a military official” after he made the mistake of wearing an old army PT jacket he’d picked up at a flea market. He lived in a procession of barely livable apartments — one with fleas, one with contaminated water, one with a hole in the floor for a toilet — and discovered a new appreciation for the amenities of home. In Versailles, he spent a winter in a tenement whose only source of heat was a coal boiler that needed to be stoked through the night. One night, a bleary-eyed missionary accidentally set a can of gasoline on fire and flames engulfed the living room. That Elder Romney experienced these things as character-building misadventures was a sign of his growing fondness for missionary life.

There was, it turned out, something liberating about struggling for a purpose greater than himself. Romney was glimpsing the peace of mind that came from setting aside personal striving for the sake of service. In a letter to his parents, he wrote, “Getting up at 6:00 — cold, tired, allergic, broke, but without a worry in the world; living for others, dependent only upon God; joy when you hear of others’ successes — where would I have ever known these things if it weren’t for a mission?” He was beginning to see his time in France as the beginning of a grand future: “If I keep in the same stream, my joy will double, triple, and be multiplied eternally. Eternal wedlock, service to the church, children, service to the world and my country! The Lord must have loved us to give us all this joy.”

As his faith deepened and his French improved, Elder Romney got better at finding new converts. But the most meaningful conversion of his mission took place back in Michigan, where Ann had been attending church every Sunday with his parents. He was surprised by the relief he felt when he received the letter from his girlfriend informing him that she’d decided to join his church. Romney had never especially cared about this before — he would have happily married an Episcopalian as long as it was Ann Davies. But his Mormon faith no longer felt to him like just a part of his heritage, an interesting heirloom passed down by his fathers. It was expanding, gaining texture, attaching itself to every part of him.

On an overcast June morning near the end of his mission, Romney climbed into the driver’s seat of a church-owned sedan and headed north toward Bordeaux with a gaggle of mission leaders in tow. He felt good. They’d just completed an eventful visit to a small Mormon branch in the southern city of Pau, where France’s mission president, H. Duane Anderson, had been summoned to mediate a feud between two elderly women that was dividing the congregation. After a day of meetings, they’d returned to their car to find it trapped in the middle of an outdoor market, surrounded by vendors’ stalls. Anderson feared they were stuck for the day, but Romney took initiative. “Il nous faut partir!” he announced to the market — “We must go!” — before forging into the crowd and doling out five-franc coins until the vendors cleared a path. It was an impressive display of initiative, the kind of thing that had gotten Romney assigned in these final months of his mission to serve as an assistant to the mission president, the highest post available to a young Mormon elder. After 21 years of hearing endlessly about his “potential,” Romney felt like he was starting to live up to it.

Later, he would try to remember those last details of the drive as he wound along the narrow, northbound roads that passed through the village of Bernos-Beaulac. President Anderson and his wife, Leola, sitting next to him; Elder Wood and the Mormon couple from Bordeaux in the back. The contours of the silver Citroën, with its long, animal hood. The viridescent landscape out the window all rolling hills and vineyards. The black Mercedes swerving so fast into his lane that he didn’t have time to honk. The crunch of metal. The shattering of glass. The screams. Were there screams?

But Romney’s only clear memory, the only thing he could be certain wasn’t reconstructed from others’ accounts, was waking up on the ground and peering up at the gray sky as a light rain fell. Then Elder Wood’s hands on his head, and the hurried recitation of a blessing, and the ambulance and the hospital and finally the news: Leola Anderson was dead.

Romney spent several days at a hospital in Bazas after the accident. He’d been in such bad shape when police arrived on the scene that, in their report, they initially wrote he was dead. In fact, Romney was merely unconscious, with a broken arm, a head injury, and some nasty gashes and bruises. While he recovered over the following days, he learned more about what had happened. The driver of the Mercedes was a priest, possibly drunk, and was going about 75 miles per hour when he collided with the Citroën at an angle that had pinned Romney’s body against the door and sent the steering column into Leola’s chest, puncturing her lung. She’d survived for a couple of hours, but the doctors were unable to keep her alive.

Leola was a beloved matriarchal figure in the mission and her death devastated Romney. He’d gotten to know her well while serving as her husband’s assistant. She teased him about Ann, offered relationship advice, served him home-cooked meals. Everybody assured him that the accident wasn’t his fault. The other car was moving too fast. There were no brake marks on the road. There was nothing you could have done. Some even suggested that he should be grateful, that perhaps he’d been saved by divine intervention, but the thought made him uncomfortable.

No one would have blamed Elder Romney for cutting his mission short, but he refused to go home. When President Anderson returned to the States to bury his wife and heal, Romney effectively ran the mission with his companion — setting ambitious new goals, offering solace to mourning missionaries, and generally staying busy enough to keep the grief and guilt at bay. But he could already feel his brush with death changing him. “Being at a point where the person next to you in an automobile dies,” he’d later recall, “and you’re in a position where you could have died — it says, ‘OK, this means something.’” Romney had become violently acquainted with the fact of his own mortality.

It was time to start taking his life more seriously.

Few would accuse Romney of leading an unserious life over the next four decades. He married Ann and raised five sons while volunteering extensively in his church. He made hundreds of millions of dollars in private equity, ran the Salt Lake City Olympics, and served as governor of Massachusetts. He even won his party’s nomination for president. But as 2012 came to an end, Romney was restless and adrift.

There is a special kind of indignity in losing a presidential race — you are at least momentarily one of the most famous people in America, but half the country hates you, and the rest see you as an object of pity. For Romney, who retreated to La Jolla after folding up his campaign operation in Boston, the months following his loss were a miserable slog. Venturing into public was a nightmare, of course. Photos of him looking cranky and washed-up spread across the internet in a blur of giddy schadenfreude: Mitt pumping gas in a wrinkled shirt, his hair uncharacteristically mussed; Mitt at the McDonald’s counter alone; Mitt looking resigned at Disneyland while gawkers snapped photos from a distance. Even at church, the one place where he expected relief, he was mobbed by admirers requesting selfies and offering condolences. He wasn’t “angry” or “despondent,” he wrote in his journal. Just “numb.”

He was proud of the campaign he’d built, the team he’d assembled, and especially the primary he’d won, protecting the nomination from other, less qualified and more extreme candidates. He believed in the economic message at the core of his candidacy, and thought he’d articulated it reasonably well. He was also proud of how he’d represented his faith. In a meeting after the election with the top leaders of the church, Mitt and Ann saw a presentation that showed a significant surge of interest in their religion thanks to his campaign, including referrals to missionaries and an uptick in baptisms. One apostle said that Ann had redefined the public perception of what it means to be a modern Mormon woman. Another told Romney that the campaign had helped bring the church out of obscurity. This was not why Romney had run for president, but the fact that he and Ann had improved the standing of their faith did bring some consolation. “That’s good enough for us,” Ann would reflect years later.

Still, Romney wasn’t sure what to do next. A few weeks after the election, he and Ann met again with Elder Boyd K. Packer, a Mormon apostle and an old family friend. After visiting for a while, Elder Packer offered to give Romney a priesthood blessing. Laying his hands on the ex-candidate’s head, the apostle offered a sacred prayer of comfort and counsel — assuring Romney that generations would be blessed by his service, that his family would benefit from their sacrifice, and that the Lord’s will had been done in the election.

One line stuck out in the blessing, because Elder Packer said it twice: “This is just the beginning.”

When the blessing was over, Elder Packer told the Romneys that he had a strong impression that Mitt’s work was not finished in government.

“I guess you don’t know much about politics,” Ann joked.

Elder Packer was adamant: Maybe you don’t know much about prophecy.

On Feb. 6, 2020, Mitt Romney walked onto the Senate floor and did something no senator had done before in history: He voted to convict a president who belonged to his own party.

Romney had not come to the decision lightly. For weeks he’d parsed and agonized over the evidence against Donald Trump, praying for wisdom. He wanted badly to go along with his Republican colleagues and vote to acquit the president — it would be so much easier. But by the end of the Senate trial, he’d arrived at the conclusion that Trump was indeed guilty of high crimes and misdemeanors.

This conclusion had come with a stomach-twisting awareness of the potential repercussions. In his journal, Romney listed the consequences he and his family might face if he followed his conscience:

The Utah Republicans that had nominated me would go crazy with anger. My colleagues in the Senate would have nothing to do with me. It would affect my ability to get any legislation passed. I’d get nothing done through the administration, of course. The president would attack me mercilessly in his rallies, incentivizing some nut job to shoot me. Fox too would eviscerate me, stoking up the crazies. The president might seek revenge, perhaps by using government in some way to hurt my sons. I would lose some friends who were Trump supporters, though not my few close friends. For the rest of my life, I would be accosted by people who hate what I had done — if I just vote with party, my vote would be expected and people who dislike Trump would just dismiss me as a callous Republican, but voting against party would engender true enmity and vitriol. It would be hard to go anywhere, especially in Utah, without the possibility of encountering some vocally hostile abuse. This would be true to a lesser degree for my sons, particularly Josh … I might need to move from Utah.

But even as Romney fretted over worst-case scenarios, the lyrics to an old hymn kept coming back to him: Do what is right; let the consequence follow. He knew what he had to do.

“As a senator-juror,” Romney said in his brief speech on the Senate floor.

“I swore an oath before God to exercise impartial justice. I am profoundly religious. My faith is at the heart of who I am.”

His voice broke and he had to pause as emotion overwhelmed him. “I take an oath before God as enormously consequential. … With my vote, I will tell my children and their children that I did my duty to the best of my ability, believing that my country expected it of me.”

The backlash to his vote was swift and savage. “Romney is going to be associated with Judas, Brutus, Benedict Arnold forever,” Lou Dobbs raged on Fox. “He’s now officially a member of the resistance & should be expelled from the GOP,” Donald Trump Jr. declared on Twitter.

Some Republicans reserved special scorn for Romney’s invocation of his faith when explaining his vote. Ed Rollins, a high-profile GOP strategist who ran Ronald Reagan’s 1984 campaign, snickered that Romney had been led astray by “whoever he is talking to in the Mormon Tabernacle Temple.” In fact, Romney hadn’t consulted any Mormon leaders on the impeachment, but church employees would later report that phone lines at the faith’s Salt Lake City headquarters lit up with angry calls from Trump supporters immediately after the senator’s speech.

In the coming days, as death threats poured in and friends cut him off and the president’s allies sought to excommunicate him from their party, Romney would think about his sons, and how they’d remember him when he was gone. He would think about his dad, the one object of little-boy hero worship he still found deserving. He would think again about his ancestors — Gaskell and Miles and Rey — and he would think of that missionary, Parley P. Pratt, kneeling on the floor of a grimy New York tenement after months of grueling, fruitless labor, receiving heavenly assurance that it had not all been in vain — your sacrifice is accepted.

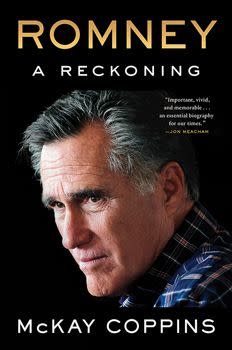

Adapted from “ROMNEY: A Reckoning” by McKay Coppins. Copyright © 2023 by McKay Coppins. Excerpted and adapted with the permission of Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

This story appears in the November issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.