Making a statement: Design for WSU and KU biomedical campus goes big

There are now renderings of what the first phase of the downtown Wichita Biomedical Campus will look like, and those involved say it’s a game-changer aesthetically — as significant as the first-of-its-kind-in-Kansas partnership between Wichita State University and the University of Kansas Medical Center to build it is.

“I believe this building will really be one that helps define our city skyline as we go forward,” said Jeff Fluhr, president of the Greater Wichita Partnership.

“It really is setting the architectural vernacular for everything that will come after it.”

The schools initially are spending more than $205 million — mostly with federal money from the pandemic economic stimulus package but also with some state money — to create an eight-story, approximately 350,000-square foot center they’ll use for WSU and WSU Tech’s colleges of health professions and KU’s schools of medicine and pharmacy.

To put the size of the building into context, WSU’s new Woolsey Hall is 125,000 square feet, Intrust Bank Arena is 330,000 square feet, and the Ruffin Building downtown is almost 400,000 square feet.

The design of the Biomedical building is as much of note as its size.

That’s partly to match the “level of inventiveness and entrepreneurial attitude in Wichita,” said Clay Phillips, principal of Kansas City, Mo.-based Helix Architecture and Design.

Helix is partnering on the design with Los Angeles-based CO Architects.

The companies spent a lot of time in Wichita not only visiting the site and exploring downtown but considering all of the city — its architecture, its history, its people and the overall culture.

When it comes to downtown architecture, “You have a little bit of everything,” said Jonathan Kanda, principal of CO Architects.

There are modern, classical and Prairie-style buildings, he said.

“You have the urban fabric to handle big, bold and expressive moves . . . in ways that are respective of the architectural history that is around you.”

WSU President Rick Muma wanted to capitalize on that.

“We’re building a facility for the future, and we want it to . . . stand out.”

He called the building “an iconic, different kind of structure.”

“It’s going to have a large presence . . . that makes a statement.”

Garold Minns, dean of the KU School of Medicine-Wichita, said the building is going to show that the city is serious about changing its core. He also thinks it will be attractive to students, most of whom are in their 20s.

“It will be a more inviting building for them,” he said. “We’re looking forward to how this impresses our applicants and our students who will be here.”

Densifying downtown

The schools expect to break ground in March or April, and it will be a 30-month build. It’s such a large building that piers have to be drilled into the ground to support it, and that foundational work along with utility work will take about half a year. That means there won’t be a lot to see until next year.

The building is expected to be ready by fall 2026.

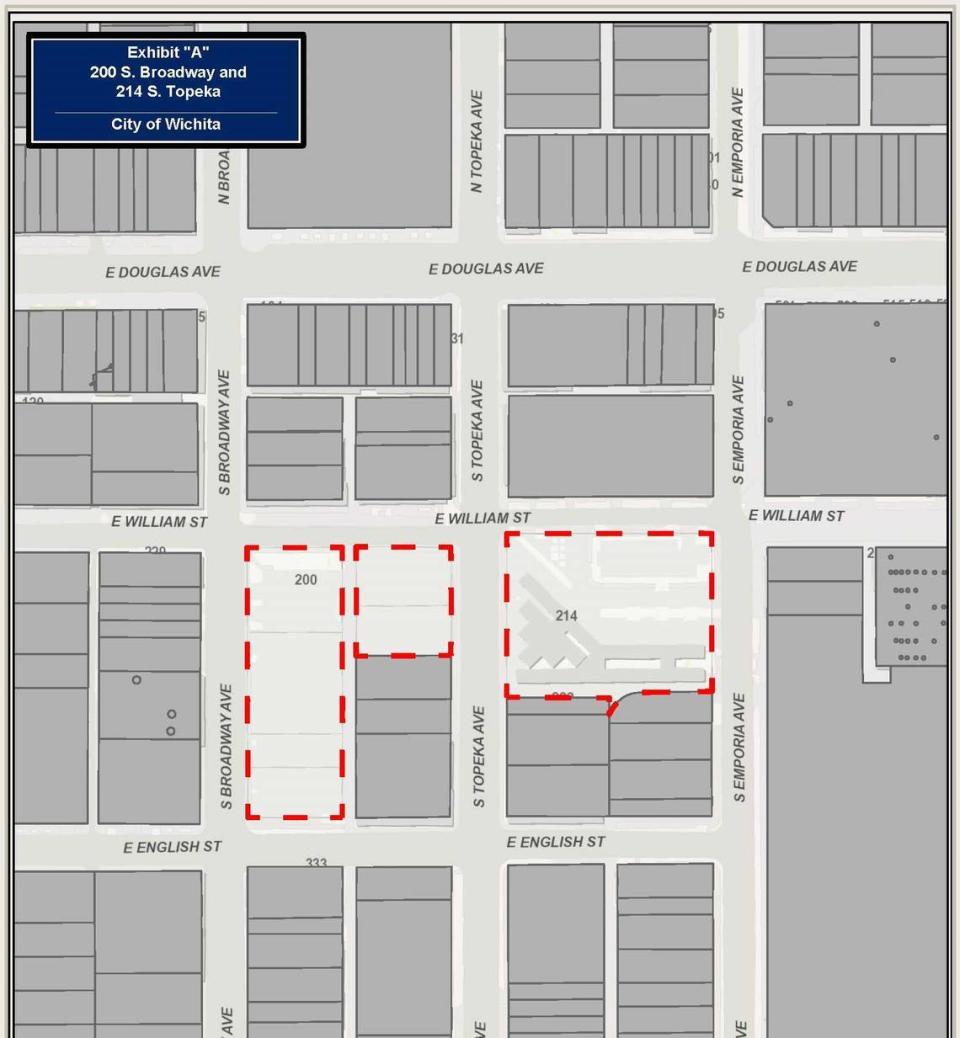

The campus has two planned sites: the southeast corner of Broadway and William where a parking lot is and the southeast corner of Topeka and William, where the Wichita Transit center is currently. It’s moving to Delano in late 2025.

The first building will be at the southeast corner of Broadway and William next to WSU Tech’s National Institute for Culinary and Hospitality Education. It will be between Topeka and Broadway on the east and west and William and English on the north and south.

Emily Patterson, WSU’s executive director of facilities planning, said the schools wanted to use as much of the site as possible — thus the eight stories.

“We needed to be thoughtful about densifying the downtown site,” she said of building higher.

Patterson said some breathing room was important, too, which is why the north end of the building next to NICHE and across from the Kansas College of Osteopathic Medicine is lower in scale.

WSU and KU purposely took into account everything else in the area.

For instance, Patterson said everyone wants NICHE to be part of the same downtown experience as the other schools, so the new building was designed to not block NICHE’s rooftop view of nearby Intrust Bank Arena.

Muma said it was important to plan how the new building fits in with the architecture around it “since we’re trying to create this environment where we’re all working toward the same goal.”

He said WSU, KU, the DO school and NICHE — with food being an important part of health — are “the beginning of a much larger health-care district.”

The new building, which is where the 17-story Allis Hotel was demolished in 1996, looks north up Broadway to NICHE, which is where the former Henry’s department store was.

On the first and second floors of both buildings, Muma said, “We’re trying to create a connection of the lines.”

While the new building has colors and finishes that blend with the older buildings around it, Muma said, “We didn’t want it to necessarily match.”

A tour of the building

The main entry to the new building is off of Topeka, one block east of Broadway, and it leads to a three-story section of the building that the architects refer to as a pavilion.

“That element, it is special,” Kanda said of the mostly glass structure. “There’s a kind of, dare I say, jewel-like quality to it.”

The entry opens into a large lobby and forum area with two-story-high ceilings.

“So that will help create some connections there,” Muma said.

There are also three 80-person classrooms that can open onto each other for larger events.

There will be a covered overhang on the pedestrian level on the north end of the building, and there will be a couple of outdoor terraces with what are called social stairs — wide stairs where people can gather or sit alone to eat or rest — leading to where the building’s third and fourth floors connect. This area is not fully designed yet, but it’s meant to give students options for places to hang out.

“In reality, students are going to be everywhere,” Muma said.

On the third level of the pavilion will be WSU’s Speech-Language-Hearing Clinic with its own entrance on Topeka. Currently, it’s at the Hughes Metropolitan Complex on East 29th Street North.

“Primarily, the first four levels of the building are Wichita State and WSU Tech spaces with offices and classes and labs and anatomy labs, PT and PA spaces and offices,” Patterson said.

The fifth floor is a shared simulation floor with simulated hospital and patient rooms along with an anatomy lab.

Floors six, seven and eight primarily will be for the KU schools of pharmacy and medicine.

There also is a mechanical penthouse floor designed to hold HVAC equipment. This makes it appear as if the building is nine stories.

The horizontal layers of the building, which will be easily visible from Kellogg to the south along with a sign on the upper part of the building, are meant in part to delineate the different uses on the individual floors.

“It’s just an interesting way to show what’s going on in the building,” Patterson said.

Designers are still working through all of the materials that will be used for the building, but there are plans for a lot of glass.

Fluhr said he loves the materials, especially the glass so people can see in to what the students are doing, and the students can see out to the people walking and driving by.

“There’s an energy with that.”

Intangible qualities

Kanda said when the architecture teams approached the project, they came in with “very open eyes” and “no pre-set opinions.”

As they toured the city, Phillips said it was to get an innate sense of its more intangible qualities.

In designing any building, he said, “It’s very much of the place and of the people.”

All the iterations of the Wichita flag they saw impressed Phillips, who lives in Lawrence. He said you don’t share your city’s flag unless you’re proud of the place where you live.

Kanda said a crucial question was “how do you place something of that magnitude in an urban environment?”

He said they had to break down its mass and be responsive to what was around it. That’s why the building has two different scales.

The lower scale is along the smaller East William Street, which the architects hope in time will develop into a pedestrian thoroughfare as a counterpoint to Douglas.

The great height of the building and its main presence is along Broadway.

The idea behind all the glass is literal and figurative transparency.

“We didn’t want people to think of this as a fortress,” Kanda said.

He described the main part of the building’s eight floors as sort of a series of floating blocks or masses.

“We are trying to make sure it feels energetic,” Kanda said.

He said the design is open to all kinds of interpretations, such as the blocks representing vertical neighborhoods for each of the schools. Others may see the big sky’s clouds reflected in the building or the color of wheat fields represented in some colors of the building.

Ultimately, Kanda said they hope whatever the reading is, people will “feel something of the spirit that’s unique to Wichita.”

“We’re trying to create an architecture . . . that people can hopefully relate to and feel like they can belong to this space.”

What comes next

Part of WSU and KU’s goal in locating in the city’s core is to use the Biomedical Campus as a catalyst in creating a larger health-care corridor downtown.

Muma said shovels aren’t even in the ground yet, and already the county has seen the benefit of locating its new Comcare facility adjacent to the school. All sides are looking at how the facility can be integrated with the campus to encourage collaboration in mental health care.

There are other beginning conversations with a number of organizations, including other educational groups, about ways to collaborate or locate nearby.

Muma noted “how consequential this will be for our community and particularly the core of our city to do something like this.”

He said the schools and the community need to further define what that corridor will look like.

WSU and KU simultaneously are working on how they’ll afford a second $100 million phase of the campus. They’d hoped to start with more than $300 million but had to scale back.

Still, Phillips said his team already has looked at where the next phase could be positioned and how the initial building may tie into it.

Some of KU’s clinics, the psychiatry department and internal medicine will remain at its current campus along the Canal Route just north of Ninth Street for now, which Minns said he doesn’t mind because the 1951 building is perfectly functional.

“We had no plans to move until this proposal came.”

Both Muma and Minns said the joint collaboration is going well.

“There’s always going to be some growing pains,” Muma said. “It’s just part of the process.”

Anytime two cultures come together, Minns said “there’s always, I guess you call them different points of view that you have to mediate through.”

“We’re still friends.”

Some of those compromises are still in discussion, they both said.

“We look forward to getting in that building and collaborating with our sister institution,” Minns said.

Fluhr looks forward to seeing what the campus will mean for more downtown development.

“It really positions our city to grow in a new way,” he said.

Restaurants and service businesses — and, yes, even a long-awaited grocery store — likely will want to locate nearby thanks to the 3,000 students and 200 faculty and staff who will be there.

Fluhr said there will be an expected 1,600 jobs generated downtown with all the development to support the campus.

He said there’s also an expected need for 1,300 new residential units, bringing downtown’s total to 5,300 units.

Fluhr called it a dynamic situation and “a testament to our community investing in itself to really prepare for an opportunity like this.”

“This project has state ramifications as well,” Fluhr said. “It’s a great elevation of an industry sector that we have, but it’s in a whole new dimension.”

He said everyone has a responsibility in building the city and preparing for what might come next.

“We cannot let up.”