‘Making too much money’: Inside Miami-Dade’s plastic surgery post-op underground

Miami — ground zero in the United States for the Brazilian butt lift, the mommy makeover, breast enlargement and other plastic surgery specialties — has achieved another distinction: It is home to a cottage industry of illegally operating recovery centers for post-op patients who need to hunker down and heal, sometimes for days.

Embedded in suburbia, the homes are engaged in a game of whack-a-mole with authorities, who look for vans disgorging bruised and bandaged passengers, and featuring back-alley garbage cans brimming bandages and other medical waste.

Often overcrowded and/or unsanitary, these unlicensed centers are “costing Miami-Dade County millions,” said Detective Gabriel Rodriguez, who has overseen a string of recent busts.

That includes one earlier this month when police raided a home on a cul-de-sac on Southwest 139th Court. They said they found 21 women jammed into the one-story, four-bedroom dwelling, 17 of whom were paying at least $250 per night as customers. Two women were arrested.

County data analyzed by the Herald — lacking some detail because of the medical privacy law known as HIPAA (the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) — suggest the recovery houses have become a persistent problem, generating scores of distress calls to fire rescue.

Recovery houses can count on a never-ending flow of potential customers — usually tourists from other states, drawn to South Florida by the area’s vast array of office-based cosmetic surgery centers. As with any operation, even out-patient ones, patients can be rendered fragile and in need of rest. They may also want to lose the just-had-surgery look before heading home.

The outfits advertise openly online, but conduct business furtively behind closed doors and covered windows in residential neighborhoods. Their social media advertisements, festooned with photos of smiling customers flaunting surgically enhanced breasts and ballooning buttocks, provide phone numbers but not addresses.

The ads suggest concierge-style luxury, including one in which a pixelated woman in a red dress rhapsodizes about a home’s charms. Reality, as represented in police photos, can be far different: blood-stained pillows, bed-side tables littered with a panoply of bandages, sport drinks, pain relievers and other miscellany, grungy bathrooms and beds wedged in side by side.

Operators occupy three- to five-bedroom homes and charge hundreds or even thousands per night per patient. Attending staffers can range from actual nurses to the untrained making less than minimum wage.

READ MORE: Researching a Florida doctor for your BBL, cosmetic surgery or plastic surgery

Don’t expect this to end any time soon. It’s too lucrative. Thanks to the seemingly unquenchable desire to look better, recovery houses do a volume business, taking in as much as $3,000 per night in the case of a three-bedroom house. The consequences for getting caught can be trifling. First-time offenders often are placed in a diversion program, which make them eligible to have the conviction expunged.

Recently, another Realtor contacted Katia Rojas looking for a “rental that she could live in but also use to assist her clients as a licensed home-care provider. Her clients only stay in the home for a few days and then they leave.”

“Is that something your client would be OK with?” she asked.

The client wasn’t OK with it. But, it wasn’t the first time Rojas had gotten such a request.

The job of investigating these homes — and, arresting those running them should they lack proper permits — in unincorporated Miami-Dade falls on Miami-Dade police’s medical crimes squad, headed by Detective Rodriguez. The unit’s plate is full, having also been tasked with investigating certain types of healthcare fraud, including Medicare rip-offs, a category in which the Miami metropolitan area is a national leader.

Officers in the unit: four.

“We’re stretched. The whole department is stretched,” Rodriguez said during an interview with the Miami Herald.

Calls for service to Miami-Dade Fire Rescue suggest the problem is widespread although Miami-Dade Fire Rescue refused to provide data that would reveal the full scope of the problem, citing medical privacy statutes.

Recovery houses thrive in a regulatory netherworld. There’s no unique license for them. For the purposes of licensing, they are the same as an Adult Living Facility or ALF, where elders live together under one roof. Those businesses obtain licenses and are inspected.

The homes nearly always operate without a license, without signage and without any outward indication that they are there. A search of the licensed ALFs in Miami-Dade on the Florida Agency for Health Administration (AHCA) website shows none containing the word “recovery.” As a result, nobody knows to look in and see if conditions are safe and sanitary.

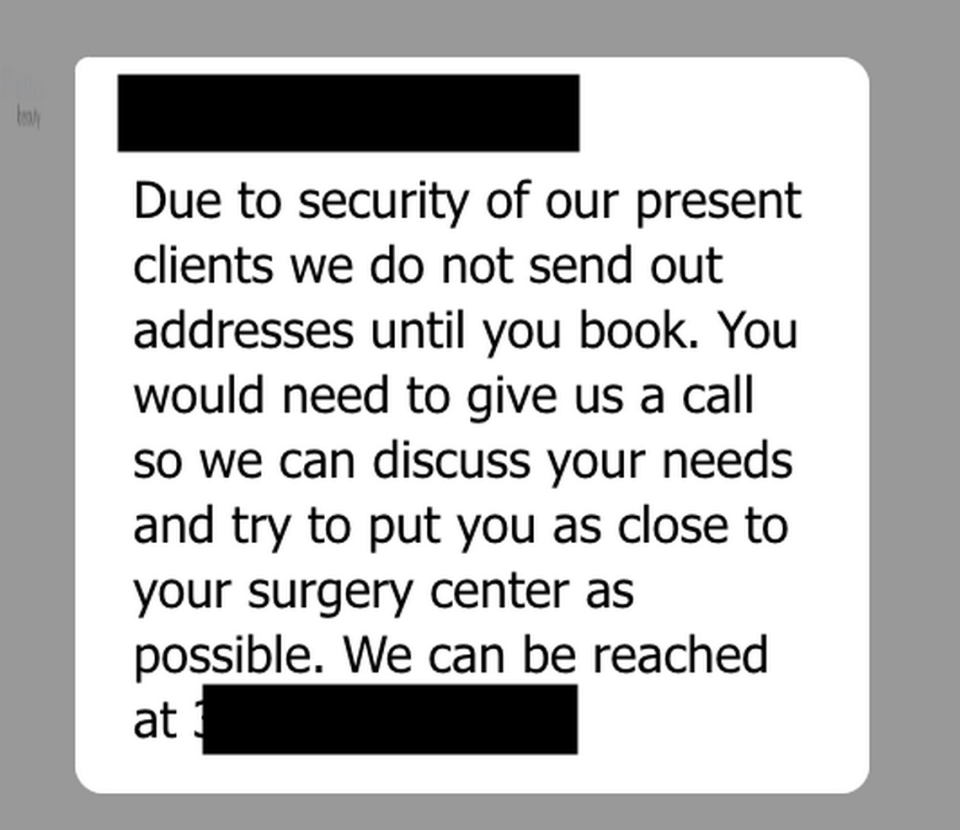

Those advertising their services online do not list an address.

An example is one recovery house that lists a Coral Gables office building on its website — but that’s not where they serve customers. When a Herald reporter inquired about the location of the actual home through an online chat, a representative wrote that they “had multiple properties throughout Miami,” but added: “due to the security of our present guests,” they do not share addresses until a customer books a stay. Among other aesthetic services, the company advertises “post-op private suites.”

Busts occur at recovery houses when suspicious activity becomes impossible to ignore. Suspicious activity can be cars or vans shuttling in bandaged individuals at regular intervals

When Miami-Dade police, accompanied by AHCA, busted a West Miami-Dade house run under the name Alpha Recovery Miami last December, 64-year-old Almarosa Davis functioned as if a licensed nurse, according to police. Davis wasn’t any such thing. Police said she had been administering injections of Lovenox, which helps prevent blood clotting.

Arrest paperwork said Davis’ daughter claimed in an email to two customers that she was a licensed nurse named “Vanessa.” She was neither a nurse nor named Vanessa. What Almarosa Davis and her 43-year-old daughter (real name Rosa Davis) actually were: felons. Both were both arrested anew.

The elder Davis is now serving a two-year probation after pleading guilty to running an unlicensed ALF and practicing nursing without a license. The younger Davis, on probation until 2029 for stealing a California nurse’s identity to rent a Miami apartment, was arrested at Miami International Airport earlier this month when she arrived from Opelousas, Louisiana.

One customer told police she’d paid “Vanessa” $2,500 via CashApp, but decided to spend her post-op time elsewhere upon seeing the “unsanitary conditions” at the house and the lack of a real nurse.

Miami-Dade Fire Rescue data

Because most homes don’t register with the state, determining the scope of the overall problem is difficult, even for a seasoned investigator like Detective Rodriguez. He operates mostly off tips. In hopes of learning more about what he’s dealing with, he made a request to Miami-Dade Fire Rescue for all calls for service since 2017 where fire rescue’s narrative included the following terms: “lipo”, “plastic surgery”, “BBL” (as in Brazilian butt lift) or “Brazilian.” He did not share his findings with the Herald.

But the Herald made a similar records request.

What the records provided to the Herald showed: From mid September 2017 through early September of this year, there were 2,199 calls to Miami-Dade Fire Rescue that included one or more of those search terms.

Over 1,500 of those calls resulted in a patient being transferred to a local hospital, for reasons ranging from hemorrhage to sepsis to cardiac arrest.

In five of the calls, the patient was already dead when rescue arrived, and in another 19 the patient suffered cardiac arrest.

Almost 200 patients were experiencing bleeding or hemorrhaging and over 100 had passed out.

This data has limitations. It did not include names and — most significantly — addresses, due to medical privacy laws, meaning the calls could have been to, say, a surgery center as opposed to a recovery center.

But Rodriguez knows the problem is bigger than his small team is able to tackle. The 20-year veteran estimates there are at least 100 unlicensed recovery homes in unincorporated Miami-Dade. The unit is able to investigate three or four a month. The financial rewards — along with minimal punishment if caught — are, Rodriguez said, a powerful incentive for people to try and operate under the radar.

Since the squad started focusing on the homes, they have made at least 26 arrests and closed down at least 23 homes.

Arrests, but minimal punishment

Examples abound of operators being staked out and arrested only to face minimal consequences.

In February, Miami-Dade police caught Traci Strader in her four-bedroom, three-bath rental home at 21900 block of Southwest 131st Place with four women in post-surgical care, one employee and two garbage bins full of bed pads, adult diapers, and bandages and medical absorbent pads “saturated with human fecal matter and blood,” according to the arrest report.

Strader, then 47, was charged with running an unlicensed ALF (a felony), felony littering and hazardous waste violation. But with no prior record, she was routed into a diversion program.

A different police unit got involved in a recovery house case this past March, but the result was mostly the same.

According to the arrest report, detectives from the Miami-Dade Police Department’s Human Trafficking unit received a tip that an unidentified woman, who had recently had plastic surgery was being held against her will in a post-op recovery home in an apartment building at 7700 block of Northwest Seventh Street. The Miami-Dade human trafficking unit and the medical crimes squad responded to the scene and determined that Maidelys Sanchez was running an illegal post-op recovery home.

According to the arrest report, Sanchez had received three previous notices that she was operating an ALF illegally, although the report didn’t state whether it was at that same location.

In an email to the Herald, an AHCA spokesperson said they did not have records of having issued Sanchez previous notices.

Sanchez, 38, pleaded guilty to operating an assisted living facility without a license, felony littering, hazardous waste law violation and a misdemeanor, creating nuisances that were injurious to health. Sanchez received withheld adjudication and was sentenced with two years probation and paid $598 in court fees.

Recovery homes don’t always operate in homes. Example: In June 2022, investigators discovered that a business called Bellas Resthouse was being run out of a hotel in Sweetwater. There were two active registrations for businesses under Bellas Rest and Relaxation LLC, but the hotel itself did not have an assisted living facility license, according to an arrest report.

While detectives were poking around, they saw a minivan pull up. Out popped the driver. She extricated a woman who was lying down in the cargo section of the vehicle. The driver walked the passenger into the hotel.

“The passenger was walking cautiously and shuffling her feet, which is indicative of post-operative cosmetic surgery behavior,” the arrest report said.

Detectives followed the women into the hotel and up to the fourth floor, where they identified themselves. They learned that Jocelyn Ramos-Rivera, now 52, had been running a business out of three hotel rooms, which at the time had five patients among them. But she wasn’t there at the time. Two employees told detectives they cared for the patients, who paid from $1,000 to $3,000 for their stays, helping them bathe, dress, use the rest room.

The outfit was issued a notice of unlicensed activity by Anne Sosiak, a registered nurse with AHCA. But it kept operating. When detectives returned days later and still Ramos-Rivera wasn’t present, they arrested her at her home.

Result: Deferred prosecution, similar to diversion.

At least one recovery home has scaled back given recent news about other homes being hit by police. This operator told the Herald her business is taking only two clients at a time — and seeing them at their own homes or in hotel rooms — as they assess whether to leave the business altogether or try to get the appropriate ALF license. The operator, who asked not to be identified, said in her view ALF rules are too strict, but that some operators do provide substandard care, and in any event it is not worth being arrested.

“I’m big on care,” the operator said. “If you have 15 people in a recovery house something is going to lack.”

Detective’s view

Rodriguez believes the rampant lawbreaking will continue unless the Florida Legislature toughens up its statutes.

He believes the ultimate solution is to require that plastic surgery procedures be conducted in a hospital setting as opposed to in outpatient clinics, as is currently the case. That way, he said, patients recovering from their surgical wounds would receive appropriate post-surgical care in a hospital setting.

In 2017, a bill came before the legislature that would have established a separate license for recovery care centers, defined as a facility where the patient is admitted and discharged within 72 hours but is not part of a hospital. The recovery care services would include “post-surgical and post-diagnostic medical and general nursing care to patients for whom acute hospitalization is not required and an uncomplicated recovery is reasonably expected; and Post-surgical rehabilitation services.”

The bill would have subjected these centers to inspections and rules. It died.

A different bill passed earlier this year gave AHCA injunctive authority (a legal move to stop a person from continuing to participate in unlicensed activity.) It doesn’t create a separate license, however..

Under that new law, AHCA may provide unlicensed activity inspection records to local law enforcement or the State’s Attorney without redaction, but it doesn’t set up a system where the recovery houses actually register, putting them on an inspector’s radar.

In Miami-Dade, the State Attorney’s Office said in a statement that there “certainly” needs to be “statutory recognition that this new healthcare related ‘industry’ has arisen and will continue to expand.”

The prosecutors’ office added: “Florida should not wait for a tragedy to occur until proper oversight is created.”