Malaria is spreading, but we can stop it

The mosquito-borne illness malaria has been spreading wider and faster as the climate changes. The disease can kill up to 600,000 people every year, per The Guardian. Malaria cases have been largely concentrated in Africa with Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania and Niger accounting for more than half of the malaria deaths between 2021 and 2022, per the latter year’s World Malaria Report.

However, multiple U.S. states have now seen cases not originating from malaria-prone regions. Prior to 2023, "locally acquired mosquito-borne malaria had not occurred in the United States since 2003," according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The good news is that a new vaccine against malaria has hit the market, which could be a turning point in disease transmission.

Why is malaria spreading?

Much of it has to do with shifting climate trends, as warmer temperatures are expanding the viable range for mosquitos. "Efforts to fight malaria are at this crossroads and have been seriously challenged by climate change," Sherwin Charles, the co-founder of organization Goodbye Malaria, told The Washington Post. "We thought we knew how to deal with this epidemic, but the complication of climate change brings different factors to bear that maybe we are not ready for." An analysis by the Post predicts that approximately five billion people will be at risk of contracting malaria by 2040.

The disease is not yet a huge risk in the U.S. as the numbers are still low. But this may not be the case going forward. "Because malaria transmission in the United States has not been a big issue, there is no surveillance of Anopheles [marsh mosquito] populations," explained Photini Sinnis, a professor at the Johns Hopkins University Malaria Research Institute. "Malaria used to come in a certain period — the rainy, hot season … but right now, throughout the year, the mosquitoes multiply," Adamo Palame, a health coordinator who works for Doctors Without Borders, told the Post.

The disease itself is not contagious between person to person and is only spread through the bite of the Anopheles stephensi mosquito. Malaria itself is a parasite found in the red blood cells of an infected person. It can cause flu-like symptoms including fever, chills, shakes, muscle aches, nausea and vomiting, per the CDC. People with weakened immune systems, children and pregnant women can have a higher risk of dying from the disease.

How effective will the vaccine be?

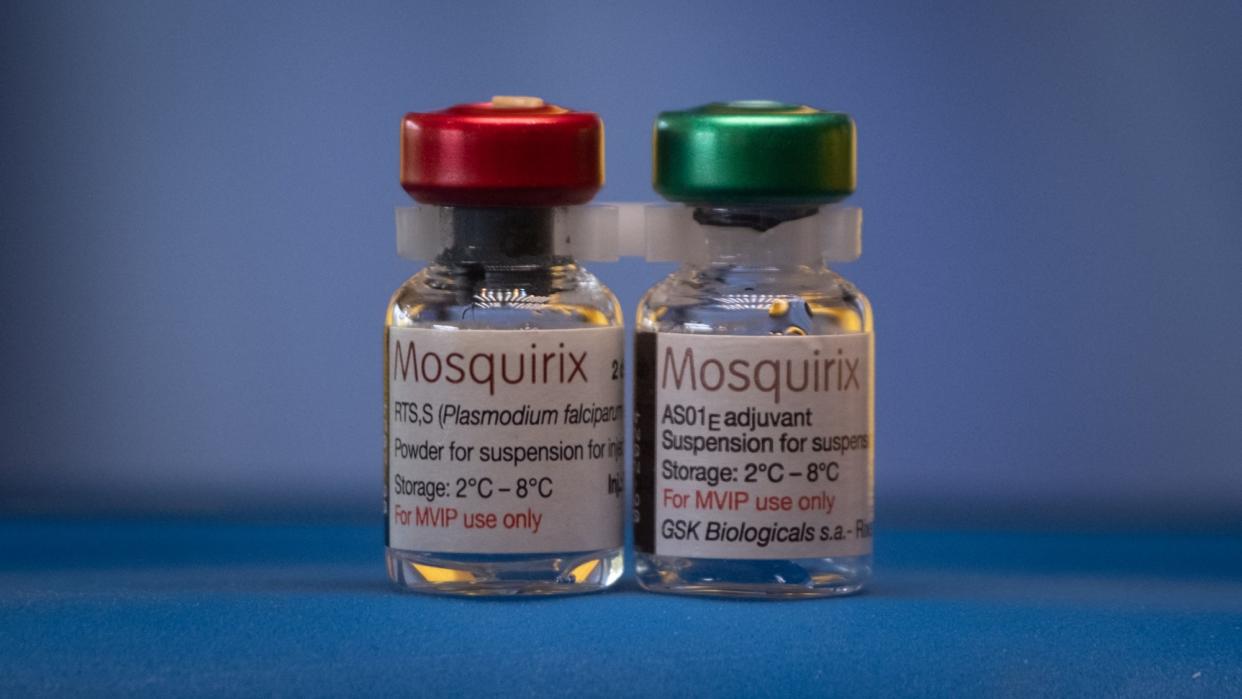

Starting next year, there will be two vaccines on the market to combat malaria. The first one, the RTS,S/AS01 vaccine, received a World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation in 2021. The new one, the R21/Matrix-M vaccine, was recommended in October 2023 and will be rolled out in mid-2024. While the makeups of the vaccines are similar, the R21 has plans to be produced in much larger numbers. "I used to dream of the day we would have a safe and effective vaccine against malaria. Now we have two," WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a statement. "Demand for the RTS,S vaccine far exceeds supply, so this second vaccine is a vital additional tool to protect more children faster." R21 will be administered in four doses, starting when the child is five months old and ending when they are two.

Many are hopeful about the vaccine’s possibilities. "This second vaccine holds real potential to close the huge demand-and-supply gap," Matshidiso Moeti, the WHO’s regional director for Africa, told The Guardian. While the first vaccine only had 18 million doses while the second is on track to have 100 million. "The estimates are that by adding the vaccine to the current tools that are in place … tens of thousands of children's lives will be saved every year," Mary Hamel, a senior technical officer with WHO, told NPR.

On the other hand, the four-shot dosage of the vaccine could pose problems for some families, who may have "travel to clinics, taking time out from the fields or hard work at home, perhaps bringing other children too," The Guardian wrote. Nick White of Mahidol University in Thailand and Oxford added that "in Africa, malaria maps to its wars," and that "large swathes of Africa will not be able to receive" the vaccine.