‘Mama bear’ shielded daughter from a mass shooter. Their relationship wouldn’t be the same

Emma McMahon and her family were near the end of a line in front of a Safeway supermarket outside Tucson. It was a sunny January Saturday morning and they were waiting to see Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, who was hosting an event she called "Congress on Your Corner," a chance for constituents to bring questions and concerns.

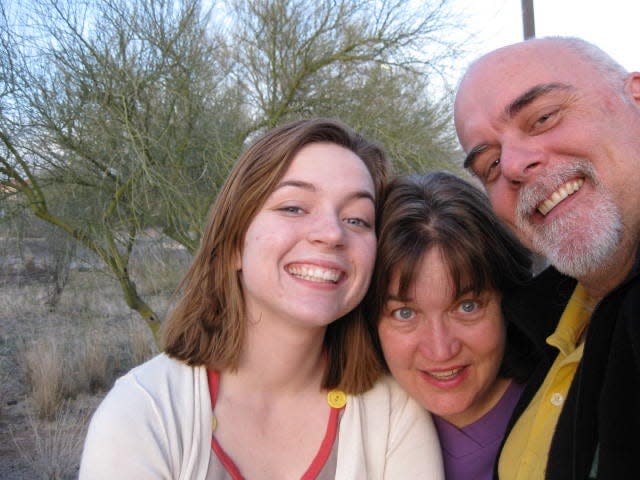

Emma, then 17, was a senior at Salpointe Catholic High School. She had worked as a page for Giffords in Washington, D.C., but somehow she'd never gotten a picture of herself with the congresswoman. That was her goal for the day.

She was making notes on a clipboard for a college essay she was working on. She was also pointedly ignoring her mother, Mary Reed, who was talking to the couple in front of them, Dorwan Stoddard and his wife, Mavy, as if she knew them.

She and her mom had been arguing a lot lately, about where she’d go to college and what she’d study. Her dad was an astronomer, her mom a software engineer. Emma was interested in economics.

Her brother, Owen, who was 13, tossed rocks against the building a few feet away. Their dad, Tom McMahon, was nearby.

Emma heard the first gunshot. What was it? Fireworks maybe.

But Mary saw the gunman. He was just feet away. Without thinking about it, she pushed her daughter against the wall and used her body as a shield.

The gunman fired under one of Mary’s arms and then the other. The bullets lodged in Mary instead. Emma covered her face with her hands.

Mary twisted around to look at the gunman.

“Little man, you had better be willing to shoot me while looking me in the eyes,” she thought.

He dropped the gun from her head and shot her in the back. Mary still didn’t move. The shooter had no idea what a mom would do to protect her children.

He was out of ammunition. When he paused to reload, two men tackled him, pinning him to the ground 5 feet away. The last woman in line grabbed the gun's magazine.

Mary finally let her knees buckle. She sank to the ground.

She was the last person shot on that Saturday morning, Jan. 8, 2011. In the end, 13 people were injured, including Giffords. Six people were killed.

What Mary remembers 10 years later is how fast it all happened.

“You hear the first gunshot," Mary said in a recent interview. She sat silent, for less than 30 seconds. “Now it’s over.”

In that time, everything would change.

If it hadn’t happened, Mary would have carried on, a congenial stay-at-home mom, volunteering at the kids’ schools, putting dinner on the table every evening at 6 p.m.

Emma might have studied science after all.

Instead, Mary became that mom.

“Yes,” Mary said, “a mama bear.”

And Emma became that girl, the one who survived.

No longer breakable

In the chaos following the attack, Mary asked Emma to call 911.

Emma paced as she talked to the dispatcher. She stepped over the gunman, still on the ground. She looked down at him and shuddered.

She hung up and saw Mavy Stoddard on the ground weeping, her husband's head in her lap. He was dead.

Only then did Emma see the blood soaking her mom’s white jeans and realize she’d been shot. Someone had brought out clean, white butcher's aprons from the store. Emma and Owen pressed them against Mary's wounds to stop the bleeding.

They watched as Mary was loaded into an ambulance, the last person to be transported to the hospital. Tom climbed into the ambulance with Mary. A family friend arrived to pick up the kids.

Emma put her arm around Owen. From that moment, she was in charge.

Her mom had been the one who took care of everyone else. She cooked, cleaned and made sure Emma and Owen got where they needed to be.

Now Emma would have to do those things.

Her mother came home after one night in the hospital. She lay on the couch, in too much pain to make it up the stairs.

Emma coaxed her to eat and drink. She held her mom’s hand when, twice a day, a home health nurse changed her bandages.

There was a constant stream of visitors. Emma offered them something to drink and answered their questions, sitting in the living room, watchful that her mom wasn’t tired or in pain.

She organized the meals people brought and fielded other offers of help. She called out-of-town family and friends to reassure them Mary was all right. She kept away the media parked outside.

As her mom had protected her, Emma did the same for her mom. It was how she could pay her back.

Mary thinks it helped, giving Emma a focus in the aftermath.

“I always think that service to others helps us stay grounded and heal from things that are hard,” she said.

Mary’s injuries were visible and healing. Her family’s wounds couldn’t be seen. Tom had hauled Owen around the corner of the building when the shooting started, so they escaped physically unscathed. So had Emma.

Mary couldn’t be sure they were healing. She arranged for the whole family to get counseling.

Her family had always been close, and the shooting seemed to tighten their bond. There was no more arguing, not about college or anything else.

Owen talked about wanting to be like Bill Badger, a retired Army colonel who was also in line at the Safeway and who helped tackle the shooter, even after a bullet grazed his head. Owen thought maybe he’d join the Army.

Emma finished her college essays and applied for admission and scholarships.

On the Monday after the shooting, Emma made sure she and Owen went back to school. She wanted something to feel normal.

One night, Emma called her friend Shelby and asked if she could come over. Sure, Shelby said, "we're just watching a movie.” That’s what Emma wanted, to hang out and watch a movie, like before the shooting.

People were treating her like she was a glass doll, careful not to joke or say something to upset her, fearful she might break.

But Emma didn’t feel breakable. She had never felt stronger.

The next turn in her life emerged from the last. One of the six people who died in the shooting was a 9-year-old girl named Christina-Taylor Green. In the aftermath, her parents established a scholarship in their daughter's name and selected Emma as the first recipient. Emma would attend Running Start, a weeklong leadership program for young women in Washington D.C.

Emma had been interested in politics since she was 9 and her fourth-grade class lobbied the town council to use a budget surplus to build a dog park. They surveyed residents and made a diorama and Emma presented their proposal.

Council members opted to buy police cars instead, but it inspired Emma. It’s why she later applied to be a congressional page for Giffords.

Her parents encouraged her to go to Running Start. She had spent an entire summer in the capital as a page so a week didn’t seem so long.

Other kids there asked about the attack, but Emma wasn’t ready to talk about it. Not yet. She felt grown up after the shooting, but the experience had also shattered her sense of security.

At first it wasn't noticeable, kept hidden under all she was doing. But Emma was anxious and more cautious about how she navigated the world, searching for the exits in every room and wary of the people around her.

She felt better away from where it happened and within seven months of the shooting, she would widen the distance further.

Letting go, finding purpose

Mary would soon confront what that distance meant. After her time in Washington, Emma received a Congress-Bundestag Youth Exchange scholarship to live and study in Germany.

As hard as Mary wanted to hold onto her daughter, she realized that she had to let go, and give her a chance to be her own girl.

“I wanted her to be able to take the world on in the way she wanted to take it on,” Mary said.

Emma left that summer for a four-week intensive language camp and then went on to Konstanz, Germany, to live with a host family and attend a German high school. It meant putting off college for a year, but she wanted to go.

In Germany, only her host family would know about the shooting. Emma felt safe, really safe, for the first time since the shooting.

Guns are strictly regulated in Germany, unlike in Arizona where Emma often saw people carrying guns on their hips or on racks in their trucks.

Now 18, she was legally an adult, and in Germany, she could drink alcohol and rent a car. She took care of herself, doing her own shopping and making her own doctor’s appointments for the first time.

Ten months later, Emma returned to Tucson a vegetarian, passionate about climate change, fluent in German and less afraid.

She felt protective of her mother and expected to take up the role of caregiver again.

But her mom had changed, too, in ways Emma had never seen before.

A ‘very reluctant activist’

Nine months after the shooting, Mary had begun researching gun violence, quietly and on her own, trying to understand what had happened to her family.

She and her husband were gun owners. They’d taught their kids to shoot.

“It can’t be the guns," Mary thought. "It just can’t.”

The statistics were staggering. The number of people shot and killed every day in America. The rate of suicide by guns. The horrifying number of children who get their hands on loaded guns.

“How, as a mother, can you justify having a statistic like that?” Mary thought. “We are a developed country! How? How? How?”

Mary wasn’t sure what to do. “I was a very reluctant activist because I was not very political,” she said.

Then on July 20, 2012, a gunman opened fire in a movie theater in Aurora, Colo., during a midnight screening of “The Dark Knight Rises.” He killed 12 people and injured 70 others, 58 from gunfire.

Five months later, a gunman killed 20 children, just 6 and 7 years old, and six staff members at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn.

“I could not in good conscience leave this problem for my children to solve,” Mary said.

Gun violence wasn’t political, although she’d learn that’s where much of the holdup is. Gun violence was a public health issue. Too many people were dying.

Later that year, Mary got a call from Mayors Against Illegal Guns, a coalition of mayors advocating for common-sense gun laws, asking if she would get involved.

“Survivors of gun violence have the moral authority to call out their elected officials and say, ‘Hey, why aren’t you doing something? Anything?’” Mary said. "This is important."

She spoke from experience.

Mayors Against Illegal Guns joined with another group to form Everytown for Gun Safety, a nonprofit organization that advocates for gun control and against gun violence. Mary is a senior survivor fellow in the organization's Survivor Network, a national group of people who have experienced gun violence.

She and Tom signed a letter published in USA Today in 2012 that called on President Barack Obama and then-presidential candidate Mitt Romney to come up with a plan to reduce gun violence.

In 2013, they joined 120 survivors of gun violence in Washington, D.C., to talk to members of Congress about gun law reforms.

Mary began to meet with lawmakers, business owners and community groups and attend rallies and legislative hearings, a congenial and approachable figure. Just a mom. That mom.

She’s hard to ignore, this congenial mama bear with scars on both arms and on her back. When lawmakers tried to walk away from her, she asked, “Why can't you discuss this with me? I lived it."

Mary tells her story and helps other survivors tell theirs, teaching storytelling classes and coaching them over the phone.

“I want to elevate their voices,” Mary said. They deserve to be heard.

‘I didn’t want to be that girl’

Emma was home for only six weeks in 2012 before she left again, this time for Wellesley College in Massachusetts.

There, she didn’t tell anyone she had survived a mass shooting.

“Part of it was I didn’t want to be that girl, and I didn’t want to accept that it shaped me,” Emma said.

Besides, how do you tell someone something like that? It made people uncomfortable.

“I am making this very scary thing real in people’s lives,” Emma said.

It became real enough without any help from her. There was the mass shooting at the movie theater and then at the school, where an entire class of first-graders were slaughtered. Every shooting brought back hers.

Nine people dead on June 17, 2015, when a gunman opened fire during a Bible study group in Charleston, South Carolina. Ten people dead and seven wounded in a shooting on Oct. 1, 2015, at a community college in Roseburg, Oregon. Fourteen people dead and 24 injured on Dec. 2, 2015, when two gunmen opened fire at a social services center in San Bernardino, Calif.

“I felt like it was inescapable,” Emma said. “It felt like no activity was safe.” Not seeing a movie, going to school, or attending church.

“It was just a stark reminder that we are not safe in this country,” Emma said. “It’s not a matter of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. It’s any time, any place.”

Her family had been at a grocery store on a sunny Saturday morning.

Emma couldn’t be silent anymore. In 2013, she did an interview with Marie Claire magazine, one of seven women who had lived through mass shootings.

Emma and her brother were the only young survivors of the Tucson shooting. It was the first time she had met others who experienced what she had as teenagers.

In the article, she said, “I decided that if you let acts of terrorism ruin your ability to enjoy life, then they win. Love is stronger than hate. But our laws must be, too.”

It was her first step.

In 2017, Emma went on a first date with a man she’d met online. He had researched her and read stories about the shooting. She was startled when he asked her about it. But she answered his questions.

Later she realized she had appreciated him asking. She had tried for so long to hide from what happened, but through therapy, she learned there was no hiding.

A year and a half ago, when Emma went on a first date with her now-boyfriend, Matthew Reese, she told him from the start.

“The longer that I wait to tell someone, the harder it becomes,” Emma said.

Matthew was shaken. He asked questions and hugged her.

“Thank you for telling me,” he said.

Surviving a shooting is part of who she is, the same as where she’s from, her interest in politics, and love of travel, baking, mountains and the smell of the desert after it rains.

“It’s an important part of who I am,” Emma said. “In not talking about that, you deny that.”

‘Adult to adult’

The relationship between a mother and daughter usually evolves over time. The changes are gradual and not so noticeable.

Mary’s relationship with Emma changed in a single day.

When Emma stepped up after the shooting and took over care of the household and her family, it was like she had fast-forwarded years ahead.

“It was like, ‘boom,’” Mary said. “Suddenly we had an adult-to-adult relationship.”

She recognized it immediately. There was a sense of equality. No longer did mom know best. Emma knew what was best for her.

“That was the biggest realization for me,” Mary said. “My daughter at 17 had a deep wisdom about how the world worked and what changes she wanted to effect. That wisdom didn’t come to me until I was in my 30s.”

Mary no longer coached Emma. She encouraged her. She didn’t offer direction, only feedback. She didn’t even help Emma pack for Germany, though she bought her a coat for the colder weather, something her daughter, born and raised in the desert, hadn’t thought of.

When Mary needed a favor from Emma, she asked, as she would anyone else. She didn't order her about like a child.

Because the sudden change stemmed from a shared experience, Mary was ready for it, though she flinched sometimes when her own words came out of Emma’s mouth, like when Mary misplaced something and Emma would reply that maybe she’d put it back where it belonged next time.

Mary had changed, too.

“I was thrilled for her because I could see something as intense as the shooting could crush her or it could free her to be who she eventually would be,” Mary said.

Mary liked and admired the woman her daughter had become.

A bond among survivors

Emma has learned to talk about the shooting without crying, though it's still hard and makes her emotional.

She gives interviews, writes articles for magazines, attends events for survivors of gun violence and speaks on gun legislation. She was at the Capitol when a universal background check bill was introduced in the House. It later passed, but the Senate refused to vote on it. Last year, her family went together to a national vigil for victims of gun violence in Washington, D.C.

Before the shooting, Emma didn’t have an opinion about guns.

She grew up with a gun in the house. Her parents sent her to shooting lessons when she was a kid. Most kids growing up in Oro Valley, 6 miles north of Tucson, did the same.

Emma didn’t think twice when she saw people carrying guns in her hometown. It wasn’t until she lived in other places that she realized it’s not like that everywhere. Now if she saw someone with a gun she would be tempted to call police out of fear or suspicion.

When a member of her college alumni group was shot, Emma contacted her, offering sympathy and resources. Experiencing gun violence is a bond. The survivors of the Tucson shooting are close, a second family to Emma and her family. She appreciates their support.

"For a long time, I felt unsafe in the world,” Emma said.

Sometimes, she still does. But she doesn't feel alone.

Ten years later, Mary still shops at the grocery store where the shooting occurred. It doesn’t scare her.

"It’s just a place," she said. A place where the unthinkable happened.

She was lucky. She lived. Her children are safe.

Emma, 27, lives in Baltimore, working as a policy and research associate for a small non-governmental organization in Washington, D.C., that works on climate change issues.

She and her mom talk or text almost every day.

Emma is proud of the work her mom is doing. Mary marvels at her daughter’s resilience.

She suspects Emma will run for office someday. “You’ve already been shot at," Mary told Emma when they talked about it. "You may as well run.”

Owen, 22, who wanted to be like Bill Badger, graduated in May from the University of Arizona, where he was in ROTC. He leaves in February for Fort Benning, Georgia, a second lieutenant in the Army.

The shooting is not something they can forget. Mary tugged at her clothes to show the scars running along the underside of each arm and the one on her back. One bullet still is lodged in her back where doctors couldn't safely reach it. The ache is a constant reminder, of what was and of what might have been.

Emma finally got that photo with Giffords. They met again at a dinner for survivors on the anniversary of the shooting in 2014.

“I would never wish this on anyone else, and I can’t say that I am grateful, but it definitely made me who I am," Emma said.

She's a survivor, like her mom.

Event will mark 10-year anniversary of Giffords shooting

Reach Bland at karina.bland@arizonarepublic.com. Follow her on Facebook and Twitter @KarinaBland.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Gabby Giffords shootings: Mary Reed and daughter Emma try to recover