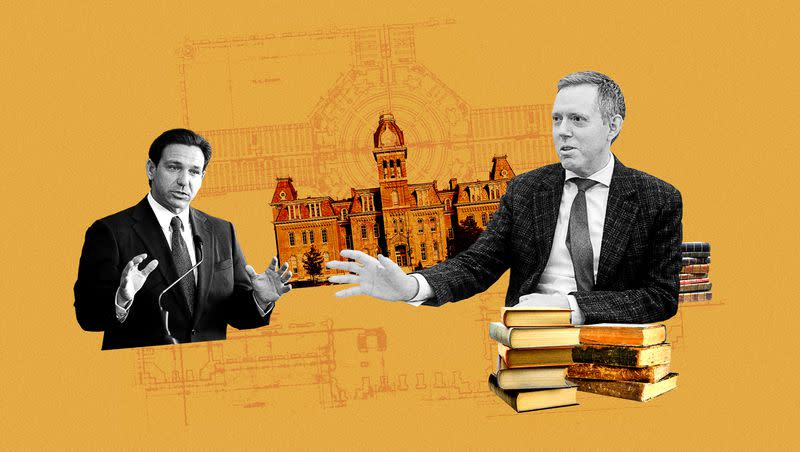

The man behind America’s most controversial high school course

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Trevor Packer had a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad year — “the toughest year of my 20 year career,” he told me. Most years, as College Board’s point person for Advanced Placement courses, he focuses on overseeing curriculum development, rolling out end-of-year tests and dealing with the occasional complaint from disgruntled students or administrators.

This year, however, the loudest complaint happened to come from one of America’s most prominent politicians: Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis.

The story goes something like this: Last year, College Board rolled out its new AP African American Studies course, assembled in the wake of George Floyd’s death and the subsequent protests. Dozens of schools were selected to pilot an early draft of the course, including five in Florida. Shortly thereafter, DeSantis’ Florida legislature passed a string of education bills, including one that affected how teachers could discuss topics like race and national identity.

Related

A schism emerged between the Florida Department of Education and College Board. Nearly everyone was left disappointed, in one way or another: students, who couldn’t take the course; parents, who either felt their children’s education was being censured or being radicalized; DeSantis & Co.; College Board & Co.; and on and on.

And then there was Packer, the soft-spoken man from Provo, Utah, stuck in the middle.

As College Board’s senior vice president over Advanced Placement courses, Packer has spent two decades oiling and rearranging the gears that make AP run, expanding the program to reach most school districts in the U.S. The Washington Post deemed him responsible for making AP “the most powerful educational tool in the country.” A scholar from a leading think tank credited him for “the rarest kind of success in public education” — expanding scale without sacrificing rigor. High schoolers nationwide know him simply as “AP Trevor,” a nod to his Twitter handle that’s amassed nearly a hundred thousand followers.

And yet, all the experience running America’s largest secondary-school curriculum machine couldn’t have prepared him for this year. Nor could his master’s and bachelor’s at BYU, or his time as an AP student himself at Waterford School in Provo, or his upbringing as the son of a stay-at-home mother and a Latter-day Saint institute teacher father.

Trying to make peace can be exhausting, he acknowledges, and he doesn’t pretend to know all the solutions. “In no way do I feel myself as having mastered this,” he told me during a recent interview, sitting in his natural habitat — the spartan offices of the College Board, located in the shadow of the new World Trade Center in lower Manhattan.

Packer is in his 50s, and he maintains a youthful exuberance — a requisite for such a job. But his well-coiffed dirty-blond hair, near his temples, now shows hints of white.

The only way to approach a culture war, he told me, is to try to find what’s true and stick to it. “Ideas themselves are not dangerous,” he said. “One-sided treatment of ideas is dangerous. And at AP, we don’t do one-sided.”

As novel as this year’s battle has been — the media coverage, the opposition from a presidential candidate, the lobbying and pressure from different political sides — Packer, to some extent, has trod this trail before.

In 2014, Packer led a revamp of the AP U.S. History curriculum. It provided a more expansive view of our country’s past than the one previously presented, including an emphasis on subjects like Japanese Americans during World War II and chattel slaves in colonial America. But the new curriculum unleashed a political uproar. The National Republican Committee passed a resolution calling it “a radically revisionist view of American history.” Republican lawmakers in red states — from Oklahoma to North Carolina to Georgia — pushed to keep it out of their schools.

Critics maintained a long list of complaints. The framework expanded its focus on African American history, from slavery to the Chicago race riots to the Black Panthers. It said European explorers were driven by “white superiority” and Ronald Reagan used “bellicose,” anti-Communist rhetoric.

It was a view of America “through the lens of race, gender and class identity,” one Georgia state lawmaker said.

But the framework, Packer insists, was just that — a draft, with possible subjects and material that were to be edited and refined. And instead of doubling down, Packer and his team listened to the critiques.

They hired a number of their loudest complainants as consultants, including Jeremy Stern, an independent historian who’d railed against the first draft. “It’s very unusual for any educational organization to respond to serious criticism by actually listening to it,” Stern later said. “The usual response is to raise the drawbridge.”

All the while, Packer kept the possibility of a standalone course on African American history in the back of his mind. Two years earlier, he’d sent a letter to colleges and universities across the country, gauging interest in an African American Studies class. There were zero takers.

The great irony of all this is that Packer — the champion of Advanced Placement courses — is only an accidental product of AP.

As a high schooler, Packer attended Waterford School, a small, private academy in Provo, where his graduating class comprised two dozen students. In 10th grade, his school decided to offer AP European History. There weren’t enough students to justify two history courses, so all 24 were automatically enrolled.

Whatever the standard of a picture-perfect AP student was, that was not Packer. He preferred Nintendo to homework. A middle school teacher, in a last-ditch attempt to spark a love of reading, once loaned him a copy of Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina.” “This book is amazing,” the teacher told him. Packer read it, all 864 pages, and was left confused as to what made his teacher love it.

It was at home, not in the classroom, where Packer’s intellectual side seemed to flourish. His mother, a college dropout, and his father, a Latter-day Saint institute teacher, were committed to getting him to college, no matter the cost. They enrolled him at Waterford on a financial hardship scholarship. They dragged him to local theater productions. They saturated their home with storytelling — Packer’s earliest memories are of his father inventing elaborate bedtime stories for Packer and his eight siblings, or of his mother, reading illustrated versions of “The Hundred Dresses” and “The Book of Mormon” out loud. By the time Packer enrolled in kindergarten, his mother had already taught him to read. When she turned the final pages of “Where the Red Fern Grows,” Packer remembers curling up on the ground and crying.

But something about classrooms left Packer uninspired and unmoved. He was a C-student in middle school, arriving in high school — to a private school chock-full of overachievers — as the so-called problem student. He trudged through AP European History, doing just enough to stay above water, but by the time the end-of-year test came around, he didn’t bother registering. Part of it was his confidence he wouldn’t perform well. But the other part was the $47 price tag — something he knew his family couldn’t afford.

The night before test day, Packer’s principal phoned his mother. They’d ordered a test for every student, and all they needed was Packer to pay the exam fee. “We think Trevor can get some college credit,” the principal said.

Packer’s mom froze. “What do you mean?” she asked.

The principal explained that passing an AP test transferred to college credit, and would mean Packer would not have to take the same course at university. Packer’s mother — whose exit from college was expedited by horrific, freshman-level courses with hundreds of students — had heard enough.

She signed a check and sent it with Packer the next day.

Three months later, when Packer received his test results in the mail, he’d gotten a 3 – the lowest possible passing grade, but a passing grade nonetheless — good enough for college credit. Out of nowhere, local universities began mailing him recruiting material. He then loaded his junior- and senior-year schedules with AP courses, passing them all. He graduated and gave the student speech at the ceremony.

“I just suddenly had a sense of myself as someone who was desired in academia,” he’d later say.

If Advanced Placement courses in high school opened new doors, Packer’s time at BYU blew them off the hinges. He fell in love with literature — reading George Eliot and Willa Cather and, yes, even Tolstoy — en route to bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English.

But in the process, he was introduced to a new world. He read prominent Black authors Toni Morrison and bell hooks and Henry Louis Gates. He took a course on Black Latter-day Saint history. He recognized a gap in his education, to that point — in high school, he’d never read Black authors or extensively studied Black history, except for a short story by Alice Walker in one AP English course.

A Ph.D. in English took him to the City University of New York, and a need for a summer job took him to a temp agency in Manhattan — which pointed him to an administrative job at the College Board’s office near the World Trade Center. His was mostly clerical work, but he loved it. At the end of the summer, College Board asked him to stay. He knew he shouldn’t — he had a Ph.D. to finish. But he couldn’t get himself to say no.

“Eventually, I loved this work more than I loved working on a dissertation,” he said. He’s been at College Board ever since.

Packer’s first two decades at College Board were punctuated by evolution. One of his first tasks, around the dot-com boom, was to build a digital system for educators to order tests. He pioneered the organization’s teacher training programs in Europe. A decade ago, after hearing complaint after complaint about the ambiguous nature of some questions on AP tests, he decided to conduct a review of the exams himself.

“One-sided treatment of ideas is dangerous. And at AP, we don’t do one-sided.”

What he found made him embarrassed: question after question asking for obscure, memorized facts — “a mile wide and an inch deep,” he said. He led a complete overhaul of the exams, focusing on allowing students to demonstrate a grasp of the information instead of prioritizing memorization. “I’m not opposed to memorization,” he said. “But for that to be the only skill we were really valuing on these exams — this can do great harm.”

They began rolling out the new tests in 2012. Packer was their biggest advocate. In 2011, the New York Times asked him if he were a high schooler, would he take the old AP biology course or wait for the new one. Packer didn’t hesitate. “I would absolutely wait,” he said.

All the while, Packer looked for new opportunities to foster some degree of harmony among the oft-dueling academics who helped craft the courses. He organized the AP Faculty Colloquia, a weekend retreat for university professors and department chairs in the subject areas AP teaches. They pore over course frameworks and debate what skills students should develop in the classes.

“It’s much easier to point the finger and cast blame when you’re not looking someone in the eye, seeing their passion and commitment to education, and hearing their values,” Packer reasons. That is more valuable than whatever the price tag of summoning hundreds of college professors to a central location for a weekend.

By the summer of 2020, when the death of George Floyd led to a nationwide reckoning regarding racial issues, Packer began once again reconsidering the feasibility of an AP African American Studies course.

In a Zoom meeting with his 300 Advanced Placement staff that August, Packer broached the possibility. He asked for volunteers. Three dozen employees signed on to help. They gauged interests from high schools and universities, this time finding overwhelming support. They collected as many existing syllabi for college-level African American Studies courses as possible. By spring of 2021, it looked like an AP African American Studies course was no longer just a dream.

DeSantis announced his Stop the W.O.K.E. Act in December 2021, vowing to fight against the “state-sanctioned racism that is critical race theory.” The news hardly registered at the College Board headquarters, where they were dealing with their own issue: building a cohesive curriculum.

Their review of African American Studies courses at universities and high schools around the country found little cohesion. Unlike courses in biology or statistics, that maintained a near-universal set of learning outcomes, a younger discipline like African American Studies was much less consistent. High school curriculum centered on movies like “42” and “Selma.” Colleges focused on more advanced readings, but there was little overlap: the most commonly assigned reading, W.E.B. DuBois’ “The Souls of Black Folk,” was found in only 22% of curriculum.

From the disparate materials, Packer’s team began assembling a framework. They compiled a set list of readings and began acquiring copyright permissions for them. They amassed a long list of potential topics to be included in the course. In early 2022, they brought together a group of university faculty to solicit their feedback.

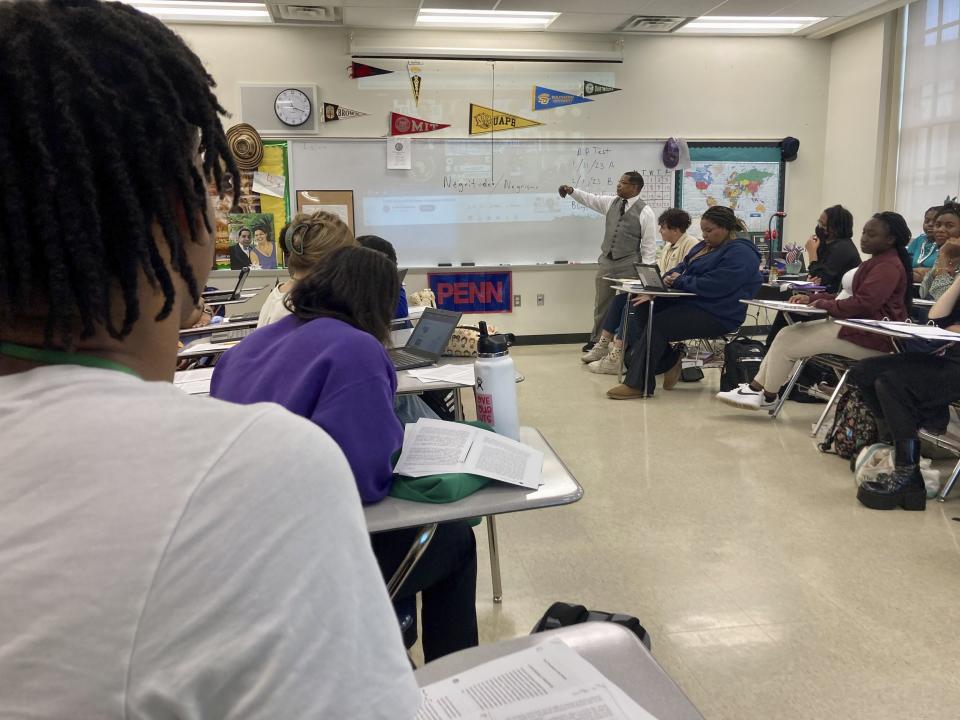

From there, they prepared a pilot program. Sixty high schools across the nation would lead out in the fall of 2022, including five in Florida. The team provided a draft of the course framework with a number of states, including Florida, to coincide with credit policies and creating a course code.

In July, College Board received a response from Florida’s Office of Articulation, asking whether the course was in violation of Florida law and requesting a review to ensure it was not. “That’s the first indication we heard anywhere that anyone might have a concern about this,” Packer recalled.

College Board conducted its own internal analysis, concluding the course did not violate any of Florida’s anti-indoctrination laws. The course covered sensitive materials and presented a range of perspectives, but it didn’t ask students to sign on to any ideology. “When you study fascism in World War II in AP World History, students are not asked, ‘Do you believe in fascism?’” Packer said. “We ask students to analyze, rather than subscribe to a belief system.” College Board notified Florida that there was no conflict.

That fall, pilot schools nationwide began teaching the course. But in late September, the Florida Department of Education sent a letter, notifying that the course could not “be approved as submitted,” citing state law. There was no detail as to which parts of the course were in violation; only that it was, and that Florida was “willing to work with College Board” to fix it.

Packer and his team were shellshocked. They scheduled a Zoom meeting with Florida officials to hear out their concerns. Jason Manahoran, vice president for AP program development, represented College Board; four or five individuals represented the Florida Department of Education.

It didn’t take long to recognize a disconnect. “What became clear very quickly is that these were not content experts,” Manahoran told The New York Times. The Florida officials quizzed Manahoran if the course promotes “Black Panther thinking,” then asked what “intersectionality” — a concept in social studies to gauge overlapping individual identities — meant. Manahoran tried to explain. The officials were “stone faced,” he recalled. (The Florida Department of Education did not respond to the Deseret News’ request for comment.)

In late January, DeSantis made his first public statement about the course. “That’s a political agenda,” he said at a press conference. Days earlier, his Department of Education had sent a letter to College Board, informing them that AP African American Studies officially violated state code. “As presented, the content of this course is inexplicably contrary to Florida law and significantly lacks educational value,” the letter said.

College Board waited to respond to the letter, as it prepared to release a full curriculum in early February. DeSantis’ accusations, Packer contends, were false. The course certainly exposed students to alternative perspectives, he maintains, but it was not indoctrinating them.

College Board released a curt statement, emphasizing that a concrete course syllabus had not yet been released. “We will publicly release the updated course framework when it is completed and well before this class is widely available in American high schools,” the statement read.

DeSantis pointed to several topics he claimed were in the course — like “queer theory” and “abolishing prisons” — as evidence it would leave students with “an agenda imposed on them” instead of an education.

“When you try to use Black history to shoehorn in queer theory, you are clearly trying to use that for political purposes,” he said.

Conservatives in the education policy space have come to DeSantis’ defense. “Almost a quarter of the course was essentially college-level critical race theory,” Max Eden, a research fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, told me. He pointed to an early copy of the course framework that had been leaked by the National Review. The last course unit, called “Movements and Debates” discussed topics like the Black Lives Matter movement and “Black feminist literary thought.”

But those topics were not a required part of the curriculum, Packer said. “‘This is a course that teaches that prisons should be abolished’ — no, it doesn’t,” Packer said. “That’s never been under consideration.”

Packer believed they should keep their powder dry and allow the new curriculum, when released, to speak for itself.

Perhaps the early curriculum was bound to frustrate conservatives. At the college level, the African American Studies discipline draws more ideologically progressive scholars than not, Eden said.

“College Board can pretty reasonably say, ‘We were trying to give a course that reflects the purview of college African American Studies,’” Eden said. “And that can also reasonably be considered to be indoctrination, because college African American Studies is a politically charged field.”

The new curriculum had passed through a gauntlet of edits, revisions and subtractions in the preceding months, thanks to input from university professors and high school teachers. Teachers were overwhelmed with the amount of required readings, so College Board decided to cut all the secondary sources, allowing teachers to assign them if they wished.

The fear of clashes with state governments — not of public backlash, but the possibility that presenting course material could cost a teacher their job, like was outlined in the Stop the WOKE Act — was also a concern. Some two dozen states had implemented measures against critical race theory. The Florida Department of Education had yet to tell College Board exactly which parts of the course violated state law, and had still effectively barred it from classrooms statewide; who was to say the same couldn’t happen in other states, and teachers could get fired over it?

Holly Stepp, executive director of communications for the College Board, described it as a “tension” — between fealty to the scholarship and creating a class that “can be taught in all 50 states.”

Those are parallel goals, she reasoned, but not everyone saw it that way: “We didn’t fully appreciate how fraught we are in this country right now when it comes to issues like this.”

When the course went public on Feb. 1, the media awarded DeSantis an immediate victory. “Ron DeSantis Schools the College Board,” The Wall Street Journal headline read. Others said College Board “caved” to DeSantis (Rolling Stone), or DeSantis “bullied” them to submission (LA Times, Vanity Fair), or any variation of DeSantis got his way, and College Board has egg on its face.

To some, that’s the story the curriculum told. Topics like Black Lives Matter, incarceration and reparations for the descendants of African slaves were deemphasized. The new required reading list wiped Black thought leaders like bell hooks and Ta-Nehisi Coates. The material could be “refined by local states and districts,” allowing increasing flexibility for educators to cover — or avoid — the topics they deemed important.

The backlash from the political left was swift. Several of the university faculty who participated in shaping the course denounced it, calling the new curriculum an “attack” on “academic freedom.” Some groups called on the longtime College Board CEO, David Coleman, to resign. Several of the leading African American Studies scholars publicly denounced the course. “We all suspected that the changes to the curriculum were prompted by political pressure,” Robin D.G. Kelley, a historian at the University of California, Los Angeles, told The New York Times.

“That’s absolutely what it looked like,” Packer acknowledged. But such a narrative, he posits, erases a year of careful curriculum evolution: removing secondary readings, adding flexibility for educators and slashing topics that could cost a teacher their job — independent of the backlash from Florida.

But again, when it came to public messaging, College Board decided to hold back, to let the course speak for itself.

But the calculus changed when the Florida Department of Education took credit for the curriculum, claiming the changes were made “by no coincidence” of its “requested revisions.” In a memo, Florida listed 20 specific changes that had been made between the original list of potential topics and the new curriculum. The letter detailed the communication it had with College Board in the process, attributing its complaints as the motive for the changes.

“That forced our hand,” Packer said.

Such a statement was completely false, he said — while it was true they’d maintained communication, such conversations were only to affirm or deny whether the curriculum was in compliance with Florida law. The state’s Department of Education had never made concrete recommendations for changes to be made to the curriculum, much less specific topics to cut.

College Board released a lengthy statement, confessing “mistakes” in its response, but noted the assertion that Florida had thumbed the scale on the final curriculum’s content was “a false and politically motivated charge.”

“Our exchanges with them are actually transactional emails about the filing of paperwork,” the statement read, “and our response to their request that the College Board explain why we believe the course is not in violation of Florida laws.”

Such conversations should’ve been brought to light months earlier, the statement acknowledged.

I visited Packer in mid-September, a full seven months since the AP African American Studies course had been released. Much has happened since. An updated version of the curriculum is due any week now, incorporating even more feedback and suggestions. A federal judge blocked portions of the Florida law that caused headaches in the first place, calling many of its restrictions on free speech “positively dystopian.”

Packer spoke about it all as if the whole saga was a distant memory, and yet with a sense of urgency. And for this reason: the whole process had bubbled up again, this time with AP Psychology at the center. DeSantis had passed his controversial “Parental Rights in Education” bill, outlining parameters for classroom discussion relating to sexual orientation and gender, leading to Florida informing College Board that the AP Psychology course could not be taught in schools.

Florida demanded College Board sign an agreement, affirming the course was not in violation of state law. College Board refused, sending a letter to educators in Florida that the status of the course was in the air.

It vowed it would never “modify” or “censor” essential material: “We are resolute in this position, in part, because of what we learned from our mistakes in the recent rollout of AP African American Studies,” the letter read.

The standoff continued until two weeks before schools opened in the fall. Some school districts in Florida wiped AP Psychology from their course offerings, not wanting to assign teachers and enroll students only for it to be canceled. Finally, days before schools would open, Florida allowed the course to be taught.

“I do value parental choice through all this,” Packer is quick to add. “We don’t support state-level censorship.”

In many school districts, like several in Utah where Packer’s nieces and nephews attend, parents are required to sign a permission slip for courses like AP Psychology where sensitive issues will be discussed. “We value a model where teachers and schools let their communities know what the topics are in an AP course, so that parents can choose,” he explained. “What we don’t allow is for one parent, or three students, to decide that a topic has to be removed from an AP course.”

But the topic is bubbling up again, this time in Arkansas, where state officials are attempting to ban AP African American Studies. This time, College Board seems to be taking a different approach — as an organization that relies on states to administer tests, it also owes students what they’re promised: a rigorous, college-level education, free of censorship.

Several hours after our visit, Packer sent me a lengthy email. He’d been thinking about one of the final things I asked — about what he’s learned from striving to make peace in one of the culture war’s biggest ongoing battles.

“I still don’t have a perfect answer,” he disclaimed, “but I continue to seek the right balance between the role of peacemaker and the role of warrior.”

You have to engage with those who disagree with you, he said, but not by fighting a battle on social media, or through insults, or through ad-hominem attacks, but by talking directly, respectfully and honestly.

Packer doesn’t claim to be the arbiter of truth, but he feels the need to defend what he sees as true. Nor does he enjoy these battles, he told me. But he’s committed to the process: of analyzing issues from many different sides. And AP, he insists, doesn’t do one-sided.