Man died in Clay County jail, unable to afford bond. His crime? Not paying child support

Ryan Everson had problems. His family agrees on that. But they also say he loved his three kids.

That’s why they think it was senseless for Clay County to put him in jail for failing to pay $50 child support installments he couldn’t afford. His children, after all, are mostly grown now. The youngest is 17.

Even his kids and his ex-wife to whom he owed the money don’t understand why he ended up dead in the jail at the age of 42.

Everson had been behind bars 10 days when he was found unresponsive in his cell on Jan. 23. The sheriff’s office said he died by suicide. Everson’s loved ones question why he was left alone in a cell after having seizures and why they got differing accounts from county officials about his death before the autopsy had been conducted.

The family also says putting Everson in jail was not going to help him become a better father. Instead of collecting any child support, the county’s actions added another death to a local jail that, by at least one measure, has seen too many in recent years.

Everson’s family said he struggled for years with a drug addiction. Noel Everson said he had talked to his older brother the night before he died. The two were close, quick to come to each other’s defense since they were young.

“It’s a sickness,” Noel Everson said of his brother’s substance use problems. “He needed some serious help.”

Missouri prosecutors used to charge thousands of people each year for failing to make child support payments. In recent years many counties across the state, including Jackson County, have moved away from that, instead pursuing child support through civil processes rather than criminal charges and jails.

But Clay County prosecutors have continued to zealously use the criminal courts to go after parents.

Last year, they filed 99 criminal child support cases, of which 88 were felonies and 11 were misdemeanors. And they sent 109 people to jail on such charges after the defendants missed court dates.

It’s just one way Missouri’s criminal justice system disproportionately harms the poor. Like many others, Everson suffered under Missouri’s historically overloaded public defense system and a reluctance by judges to follow state guidelines meant to release more nonviolent defendants from jail with lower bonds.

Held for a crime of poverty — not violence — Everson’s bond was set at a price he could not pay. And partly because he could not afford an attorney and did not get a public defender to argue for the county to follow state guidelines and release him on a lower — or zero cash — bond, he stayed in jail until he died.

“The justice system is set up for the privileged,” Everson’s older sister Erin Swart said. The family believes the county’s decisions failed Everson — and his children — at every step, from issuing a warrant on the underlying child support case to setting a $10,000 bond and keeping him in jail without the treatment he needed.

Alexander Higginbotham, an assistant prosecuting attorney for the Clay County Prosecutor’s Office, said the office pursues child support cases so aggressively because they are trying to make parents behave better. He also said incarceration is generally the “last resort” in such cases.

Clark Peters, a professor at the University of Missouri’s School of Social Work and Truman School of Government and Public Affairs, said he doubted whether there was evidence that Clay County’s methods achieve the results they say they want.

“Certainly I have not seen one study that suggests that this actually creates better parents,” Peters said.

Instead, he suggested, the better path would have been access to drug treatment.

“If this were a cousin, a nephew, a brother, what would we want? I can’t see how jail would factor in,” Peters said. “We would want treatment that is effective, prompt, that is available, that is flexible. If we want to make this gentleman a better parent, it doesn’t strike me that incarceration is the fastest, best path to achieve that.”

“But we tend to get angry at these people and there’s good reason for that frustration, but frustration and anger aren’t good guide stars for good policy. The better path would be treatment. Let’s get him to a place where he can earn money in the legal labor market and then get to a place where he can provide for his children.”

From the wilds of Alaska to Missouri

Everson met Shawna Almendarez in kindergarten in Alaska.

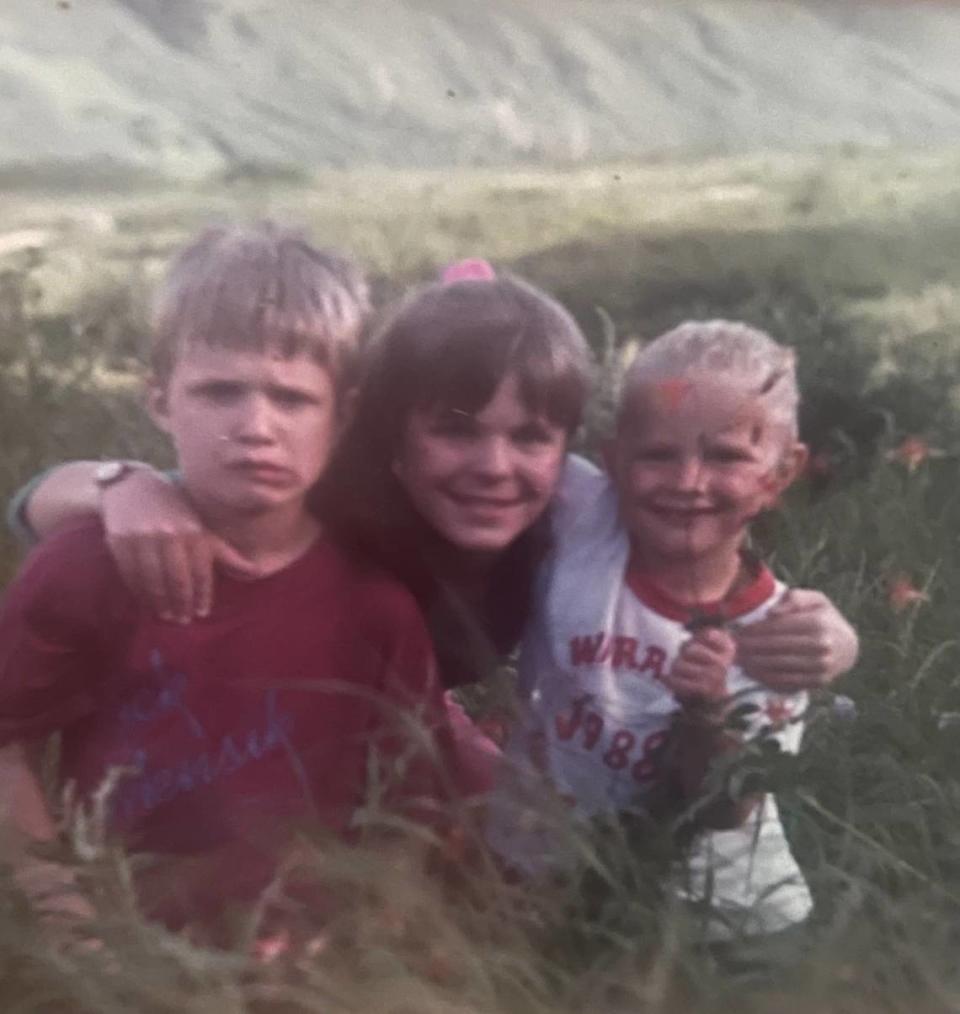

He was the middle child of three. His mother was a single mom. The family of four was tight-knit and protective of each other. When someone teased or made fun of one of the siblings, the others would jump in to defend them.

They grew up in the Fairbanks area, with the outdoors in their backyard. When there was a massive snowfall, the kids would sled off the roof of their garage. During the summer’s long days when the sun didn’t set, they stayed out biking across dirt hills and camping near a small seaside town where they would jump into the freezing water and devour s’mores.

“I remember so many adventures of us running through the wilds of Alaska,” Swart said.

Everson was good looking and funny. Swart recalled with a laugh how he and his brother would reenact the Hanz and Franz bodybuilding skits from Saturday Night Live, famous for the catchphrase “We want to pump you up!”

During his middle school and early high school years, Everson excelled at soccer, competing on a travel team.

His friendship with Almendarez continued and when they were teenagers, he asked her out.

Everson fiercely defended those he cared about and would get into fights with anyone who messed with his friends, recalled Troy McMillan, a close friend from his high school years. The two would go to parties together, first stopping at a reuse site to collect pallets and discarded furniture to use in bonfires.

But the two drifted apart when Everson started hanging out with a rougher crowd.

His relationship with Almendarez grew more serious around the time they were 18. The couple had a son, Rielly, when she was 21 and then two daughters. They married and Everson was working as a carpenter, a craft he had became skilled at.

But he gradually got deeper into drugs. That led to their divorce and his downward spiral worsened, Almendarez said.

When he was around his children, he was awesome, she said. Harkening back to his childhood in Fairbanks, Alaska, they would go on adventures, from nature hikes to making forts outside and ax throwing.

But those times became rarer as the years went on.

She moved to Missouri in 2015 and he followed.

“He loved his kids and he wanted to try to be near them,” she said.

Child support charge

Everson lived for a time in an Independence home where a fire left behind smoke damage.

Before that he had bounced around, staying with a friend and even in an abandoned house. He didn’t have a permanent address or a car, his brother said.

He scraped by without a job. He saw his kids, now 17, 19 and 20, when he could and would buy them things they needed or presents when he had money.

In one video shared by his family, he is seen with his arms wrapped tightly around his youngest daughter, Nautia Everson, jokingly not letting her leave his grasp as she laughs hysterically.

Macy Everson said her father was “a big teddy bear.” Though he hadn’t been around the past couple of years, they messaged all the time.

“If anything, he didn’t love himself,” Almendarez said. “But he loved his kids.”

In 2008 in Alaska, Everson was ordered to pay $458 in child support every month, according to court records. Five years later, the amount was modified to $50.

That agreement carried over when they moved to Missouri and the state’s Family Support Division took over the case. When enforcement there fails, cases are referred to the prosecuting attorney for review.

Last May, Clay County prosecutors charged Everson with one count of criminal non-support.

They alleged he owed $30,272 in Alaska and had missed $600 in payments in Missouri over a year, making the offense a class E felony, punishable by up to four years in prison.

Even though Everson had never paid child support, Almendarez said she did not want to see him charged. She had accepted she wasn’t going to get the money and that jailing him would not help him get a job or communicate with his kids.

Noel Everson said charging his brother was not going to help him be a father.

“Doing that is not a positive,” he said. “There needs to be some serious, serious reshaping and remolding of the system there. It’s ruining people’s lives.”

Ryan Everson was issued a summons, but he did not show up to the July 7 court date. It was on that summons that a warrant was later issued and he was booked into the Clay County jail.

Other jurisdictions across Missouri have turned away from prosecuting parents for failing to pay child support. In 2012, Missouri prosecutors filed 3,108 felony charges for nonpayment of child support, according to records from the Missouri Department of Social Services.

By 2022, that number had dropped more than two-thirds to 897.

Had Everson’s troubles been just south in Jackson County, for example, he might still be alive. There, child support cases generally go through civil court instead of criminal prosecution, so parents don’t typically go to jail.

The Jackson County Prosecutor’s Office has not filed a criminal non-support case since 2020, though the prosecutor’s office recently changed its policy and expects to file a few misdemeanor cases this year.

Spokesman Mike Mansur said they first attempt to get a payment agreement in place or refer the parent to an agency that can help with employment.

If that fails, a civil contempt action is filed. In most cases, the case gets resolved with an informal agreement. It can go to trial before a family court commissioner. If someone fails to comply or appear, a warrant could be issued.

“We have good success collecting regular child support payments,” Mansur said. A total of $821,767 was collected by prosecutors in Jackson County last year.

In Clay County, assistant prosecuting attorney Higginbotham declined to say how much child support prosecutors there have collected.

He said the prosecutor’s office takes “a very holistic approach to establishing and collecting child support.”

Defendants are initially issued a summons — not a warrant — and arrest warrants are only issued if a person fails to appear for their court date. Whenever summonses are returned undeliverable, he said, the office’s standard practice is to agree that defendants be released on a signature bond with the added condition that the defendant will pay child support.

Parents in Clay County can have their cases dropped if they successfully complete a court-supervised diversion program that offers financial management classes, Higginbotham said, and can work with a specialist to help them find employment, housing and substance abuse treatment.

“Our goal is the collection of child support for the children of Clay County, so incarceration is always the last resort as resolution of a child support case,” Higginbotham said.

“A wide range of actions, including administrative enforcement, civil contempt filings, and lastly criminal probation, are attempted before noncustodial parents are sentenced to jail or prison on a child support case in Clay County.”

Bond conditions

Everson was picked up by police in Raytown on municipal charges and transported to Clay County’s jail Jan. 12. Clay County Judge Louis Angles set bond at $10,000.

Noel Everson said the bond amount did not make sense given that his brother could not pay $50 in child support a month. As a result, he would remain in jail.

“Ryan was judged and guilty and sentenced,” he said.

On the evening of Jan. 22, Noel Everson talked to his brother, who had been in jail for 10 days. Ryan Everson promised he would be at his brother’s wedding this June in Hawaii. He wasn’t happy he was in jail, but he didn’t seem depressed or distressed, Noel Everson said.

His brother’s case could have been handled differently.

In 2019, the Missouri Supreme Court issued guidelines saying courts should impose the least restrictive conditions for release. That must be weighed against community safety and the need for defendants to show up in court.

Higginbotham said the court considered Everson’s criminal history, the number of times he failed to appear in court on the child support case as well as other cases and his time living out of state with outstanding warrants. Everson had failed to appear at court dates at least three times dating back to 2017.

“With such considerations in mind, the bond set in this case was not an unusual amount,” Higginbotham said.

The bond was reduced on Jan. 20 to $5,000, court records, which have since been deleted, said. But Everson could not afford that either.

As part of his bond conditions, Angles, who declined to comment and later did not respond to emailed questions, also ordered Everson to pay the monthly $50 child support.

Matthew Mueller, a Missouri attorney who has challenged prosecuting criminal non-support cases, said that condition was “not really appropriate in the context of law.”

“The purpose of bond is to make sure that the person comes to court and does not otherwise break the law, and so it’s always odd for me for a condition like this to be put into a bond because that’s really not the purpose of bond,” Mueller said.

As the bail system disproportionately affects the poorest, groups have formed so-called community bail funds. The organizations, often nonprofits operating on funding from donations, assist people who are unable to pay their way out from behind bars.

One local group is the Kansas City Community Bail Fund, which opposes the use of bail entirely and favors a system where those facing charges are not jailed based on their ability to pay. In a statement to The Star, Chloe Cooper, the organization’s executive director, said the system is one that “preys on the poor and criminalizes poverty.”

“While behind bars they could lose their homes, jobs, and everything they’ve worked for,” Cooper said, adding that the situation also creates challenges for those seeking to prepare a legal defense. “For those in our country experiencing poverty, ‘innocent until proven guilty’ does not necessarily apply.“

In a review of the case, Mueller also expressed concern about the fact that Everson was not represented by an attorney.

No attorney

When Everson appeared by video in front of Angles on Jan. 17, there was a prosecutor present to argue he be held in jail on a bond, according to court records.

But Everson did not have a defense attorney.

Mueller said defendants are put at a disadvantage without a lawyer, which is constitutionally guaranteed at critical steps in a case, and many end up giving incriminating statements in court.

“The big issue is, had the defendant been provided counsel, he would have had a much better chance of securing his release from custody,” Mueller said. “It harmed him because he remained confined after that bail hearing. Would it have been different if he had a lawyer? We’ll never know. But it couldn’t have hurt.”

Noel Everson said it was another part of the process that he felt was unfair. His brother did not know anything about the law and having an attorney could have helped him present a case to get released, he said.

“You should have somebody be able to be there to be your voice and to talk for you and to know your rights,” Noel Everson said.

Ryan Everson pleaded not guilty and was advised to apply for a public defender. A public defender was assigned to the case the day he died.

“It was just a total collapse of the justice system,” Noel Everson said.

Thousands of people across Missouri don’t have the money to hire a private attorney. The public defender system has been chronically underfunded and overloaded. That often leaves defendants standing in front of judges alone.

Like most places in Missouri, Clay County does not provide counsel at every stage of a criminal case.

But one jurisdiction in the St. Louis area does, and if Everson had been arrested there, his life again might have turned out differently.

At the beginning of this year, St. Louis Circuit Court expanded its bail hearings, spokesman Joel Currier said. Those who are detained are brought to court — instead of appearing by video — where they can meet with a court-appointed lawyer.

The private attorneys are under contract with the court, which budgeted about $70,000 per year for that service, according to Currier.

The new process gives defendants up to an hour to discuss their case before it is called by the judge, apply for a public defender to take over the case and get connected to community providers.

Mueller said this set up, or something similar, should be happening at arraignments and bond hearings across Missouri.

“An argument I often make is, a prosecuting attorney is always there, right? They’re making recommendations for bond,” he said. ”They will make legal arguments as to why the person should remain confined. And if you’re going to let the prosecutor do it, you have to provide the same right to the defendant i.e. giving them a lawyer to make compelling legal arguments on the other end.”

Deaths in county jail

Everson’s death was one of three in the Clay County jail in 21 months.

In January 2022, Donje E. Lambie died of an apparent suicide in the detention center. Eight months before that, authorities said Candi Hyatte died from a drug overdose.

The prisoner death rate is more than twice the national jail death rate, according to data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics and the Clay County Sheriff’s Office.

The federal agency calculates the rate based on a jail’s average daily population. But Sarah Boyd, a spokeswoman for the Clay County Sheriff’s Office, said when calculated by the total number of people booked in annually, the county’s number is much lower than the national rate.

“Obviously it is incredibly concerning for us on the rare occasion someone passes away in our custody,” Boyd said. “We go to great lengths to ensure their safety, and often that means putting measures in place to protect inmates from themselves. But even those can be insufficient for some who are intent on taking their own lives.”

All three families spoke with The Star and said they still have questions.

Lambie, 41, was serving a 30-day sentence on municipal charges. Her father, Denny White, of Topeka, said his family is still grieving and he continues to question how she was able to kill herself in jail.

Boyd said the jail has a separate housing unit with additional supervision for those on suicide watch. Everson and Lambie did not exhibit any signs they were contemplating suicide, Boyd said.

“Had they done so, they would have received the intensive supervision and care we provide to keep them safe,” she said.

When prisoners are booked in, they undergo a medical and mental health assessment and detention staff are trained to look for suicidal tendencies.

“Despite all that, we cannot read their minds or ever know what prompts someone to consider such a drastic measure,” Boyd said.

Hyatte was taken into custody in May 2021 for allegedly using a fake ID at a casino. Police also said they found drugs in her bag.

The 41-year-old woman complained of shortness of breath when she was being booked in. Like Everson’s family, her daughter Kaylee Creach, 18, wonders if her loved one received proper medical attention.

“It’s hard for me to believe anything and realizing that nobody ever gets clear answers, it disturbs me,” Creach said. “These families are left to question what happened to these loved ones. We can’t find closure.”

Everson’s family said the sheriff’s office stopped answering their questions, citing the ongoing investigation.

Boyd said detectives share as much information as they can without jeopardizing the investigation with families of those who have died in jail as they would in any other death investigation.

The family said they had concerns about his seizures and wanted to know if that played a part in his death. He had been taken to the hospital a few days after he was booked in for seizures and then returned to the jail where he was placed on medical watch until Jan. 20, Boyd said. His family plans on having a forensic pathologist review the autopsy results.

“The uncertainty makes it worse,” Noel Everson said. “I don’t know what to believe.”

Ryan Everson would have turned 43 one month ago, on March 23. A fundraiser was started to help with his funeral costs. A service is planned for June in Kona, Hawaii, where his ashes will be spread.