The Man Who Made the Suburbs White

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This essay is adapted from Kingdom Quarterback (Dutton, 2023), a book about how American cities grew, how they failed, how they are changing, and why football matters so much to them, told through the narrative of Patrick Mahomes and Kansas City.

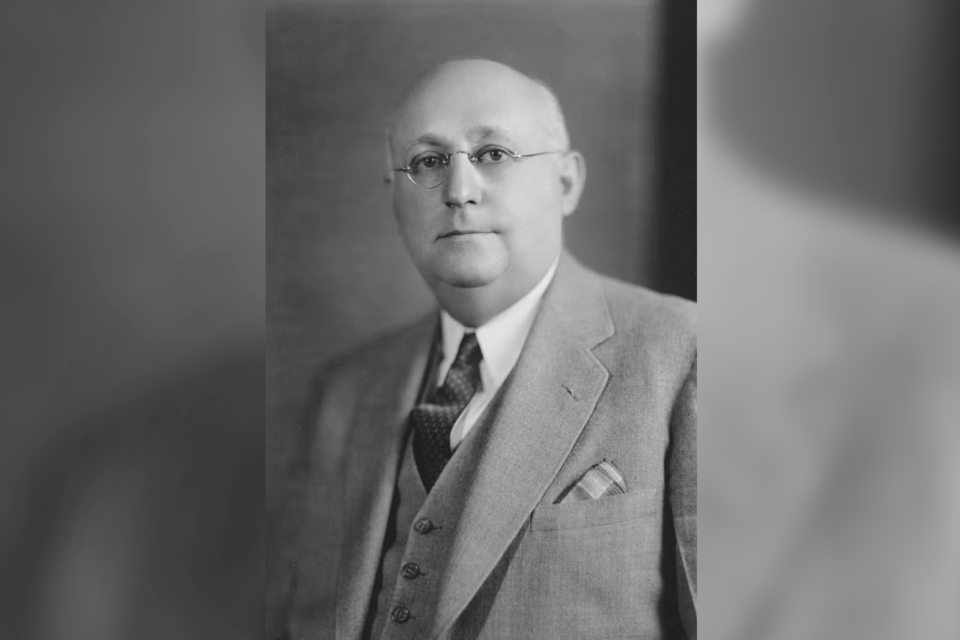

Six months ago, on the day Kansas City, Missouri, threw a Super Bowl parade for the NFL champion Chiefs, not everyone was focused on superstar quarterback Patrick Mahomes. Legislators from the Kansas City area and across Kansas held a hearing at the Statehouse related to another figure who left a mark on not just the heart of America, but all of it: J.C. Nichols, one of the most influential American developers of the early 20th century.

The lawmakers considered a bill that offered jurisdictions in the state an opportunity to remove racial housing covenants, a tool Nichols popularized and which, incredibly, were in many places still visible on housing documents. The covenants had been illegal for decades but remained as a vestige of the past and helped explain why so many communities effectively excluded racial minorities in the present. Rep. Rui Xu, a Kansas City–area lawmaker who lives in a Nichols-built suburb, later said he could still see the covenants’ remnants throughout his district, which includes communities that are around 90 percent white.

“We are still wrestling with the effects of policies from decades and centuries ago,” Xu told his fellow legislators.

When my co-author and I set out to write a book about Mahomes and the transformation of Kansas City, we ended up writing nearly as much about Nichols, a forgotten figure (at least outside Kansas City) who developed or popularized many of the legal and aesthetic innovations that made much of American suburbia what it is today: attractive, exclusive, and mostly segregated. His ideas are visible nationwide, residing in meticulously planned cul-de-sacs, in spacious lawns, and in every pitched battle over efforts to build more-inclusive neighborhoods.

Today, for most Americans, Nichols is an anonymous figure. But, as a U.S. senator opined on the floor of the Capitol decades ago, “there are few cities of large size in the United States that in one way or another have not felt his genius.” In 1999 Builder magazine listed Nichols third when it counted down 100 of the most important figures in American housing during the 20th century (behind only FDR and Henry Ford).

When Nichols started planning communities, in the early 1900s, developers were largely derided as “curbstoners.” They bought property, divided it into lots, threw down curbstones, and moved on, oblivious to the future well-being of homebuyers. A transformative idea dawned on Nichols: stringent restrictions.

Also known as covenants, they’d existed for decades, typically as an agreement between a developer and buyer on a single lot, proving unpopular to Americans who didn’t want to be controlled on their own property. But Nichols sensed he could foster long-term stability, which would be profitable for him and for homeowners. He initiated restrictions on entire neighborhoods, placing them on the land before any lots were sold—a private zoning system before municipal zoning was widespread. He’s credited as the first developer to emphasize the covenants for middle-class areas and to make them self-renew after periods of 25 to 40 years unless a majority of residents objected, ensuring they’d essentially last forever. For enforcement, he set up homeowners associations.

Nichols’ restrictions started with a few sentences on neighborhood plat documents and eventually ran for a few pages. They set minimum prices for home construction, mandated single-family housing and banned apartments, required a specified amount of space on the fronts and sides of homes, and regulated routine housing elements like chimneys, trellises, windows, vestibules, and porches.

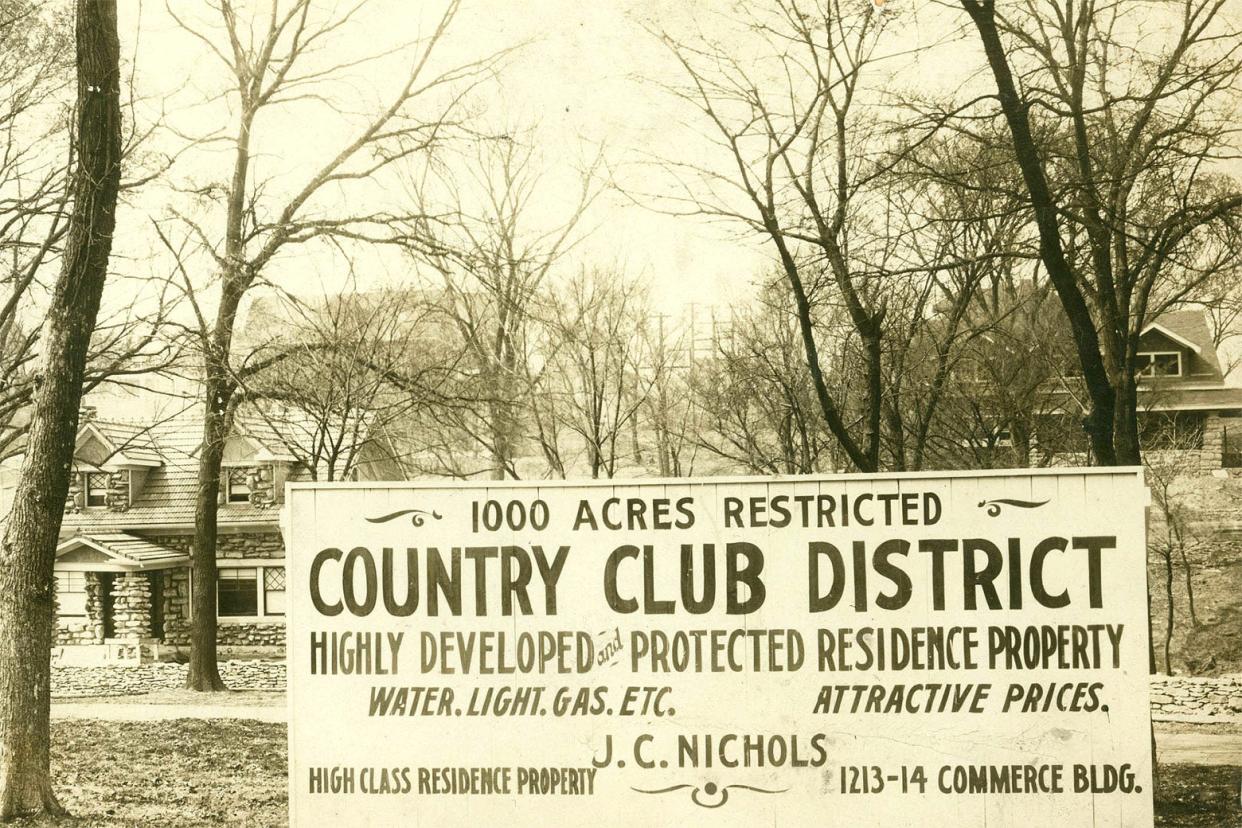

There were also racial restrictions that barred Black residents from owning or renting homes. An early billboard for Nichols’ Country Club District development described the area as “1,000 Acres Restricted.” Newspaper ads claimed that Nichols’ neighborhoods blocked “all undesirable encroachments” and promised that “complete uniformity is here assured.”

“Uniformity” proved to be a helluva business for Nichols: “And we find that the more restrictions we can put on,” he wrote in a 1923 Good Housekeeping essay, “the more cheerfully is the land bought.”

Nobody had seen a swath of suburbia as vast his neighborhoods, which comprised the Country Club District: By the 1940s there were more than a dozen contiguous upper-class and middle-class subdivisions filled with bubbling fountains, tree-lined vistas, and cul-de-sacs, providing homes for as many as 50,000 people across two states. Many subdivisions were buffered by parks and golf courses, and they were all tied together with restrictive covenants. It was the “American’s domestic ideal,” opined a visitor from the New Republic.

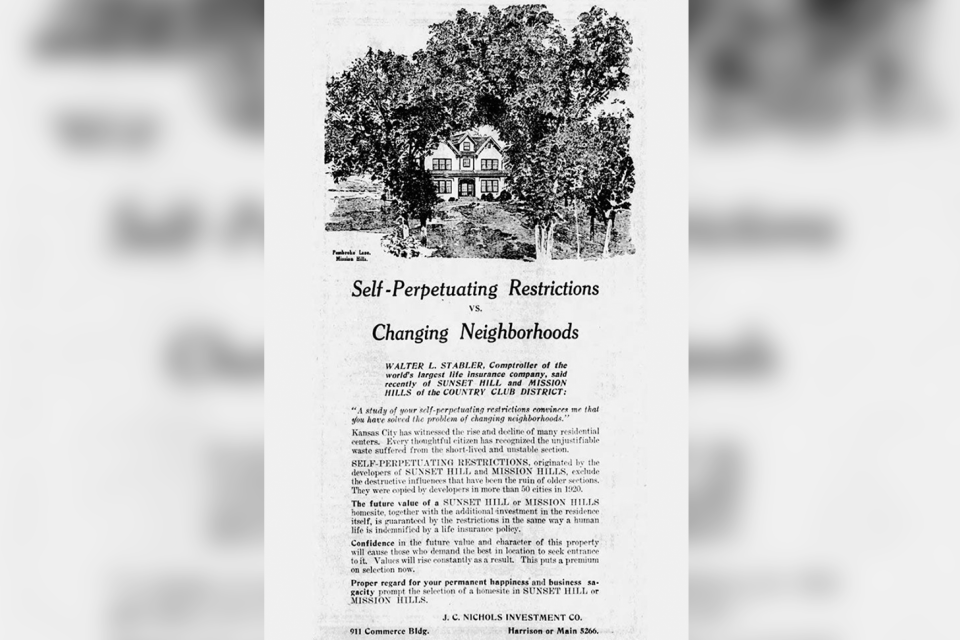

Nichols wasn’t the only builder applying covenants. Their use accelerated after 1910, imposing segregation and strict land-development rules across the country. But he was their most prominent proselytizer, promoting their spread through speeches and articles and in leadership roles with national real estate organizations. Nichols’ covenants in Sunset Hill and Mission Hills, two of his poshest neighborhoods, were said by his company to have been copied in more than 50 cities.

In the 1930s, the Nichols Way received a boost from the federal government. As the Great Depression wore on, he and other renowned developers began pushing for an organization to stabilize the housing industry. One result was the Federal Housing Administration, a New Deal agency that became infamous for systematically refusing to insure mortgages in Black and lower-income neighborhoods and subsidizing a white exodus to the suburbs.

Developers seeking FHA insurance followed a manual that recommended that restrictive covenants be set for entire subdivisions before homes were built and advised using them to maintain single-family-home uniformity and to prohibit “the occupancy of properties except by the race for which they are intended.” It also included standards for oddly specific details, like the amount of space on the sides of homes. Restrictive covenants, the manual noted, “are apt to prove more effective than a zoning ordinance in providing protection from adverse influences.”

To Kevin Fox Gotham, a professor of sociology at Tulane University and author of Race, Real Estate, and Uneven Development, it seemed as if the FHA had “adopted [Nichols’] methods and practices almost verbatim.” Or as Sara Stevens, associate professor at the University of British Columbia, wrote in a Princeton dissertation that led to her book Developing Expertise: Architecture and Real Estate in Metropolitan America: “[Nichols’] innovations in deed restrictions created the legal foundations for the permanence of the suburban pattern.”

The result was that many suburbs and the outer edges of cities across America developed with Nichols’ DNA. And they still have it today.

America’s suburbs have diversified, but they’re still heavily segregated. As the Brookings Institution put it in 2020, “White people and people of color largely do not live in the same suburbs.”

Although racial covenants are illegal, other self-renewing restrictions—the zealous attention to land use and building standards propagated by Nichols—remain on the books in many subdivisions across the United States (with many more added to new subdivisions in recent years), helping maintain segregation by race and income. Roughly 20 percent of Americans live in an area governed by a homeowners association that enforces restrictive covenants, and Stephen Miller, a professor at the University of Idaho College of Law who has studied housing covenants, told me most covenants contain a standard from the Nichols playbook: a requirement that the lots be used for a single-family-dwelling unit. This particular restriction acts as an extra barrier that overrides municipal zoning codes. Even as Americans say they support more low-income housing and want to live in ethnically diverse and walkable communities, the restrictive covenants contribute to the inflated home values that have turned many middle-class neighborhoods into affluent enclaves—not to mention places where you can’t walk to stores, restaurants, or offices, and where, even if they wanted to, developers cannot build multifamily buildings.

“The reason why that happened … in suburban environments isn’t just about zoning,” Miller said. “It’s about the [covenants].”

But the legacy of Nichols survives not just in the suburban aesthetic and the legal framework that produced it. It also resides in the American instinct to prioritize homeowners. The formalization of Nichols’ covenants by the FHA and their promotion by real estate groups, Stevens wrote, led to a tendency for municipal planning departments to “support the needs of individual property owners (as a special interest group) above the general population.”

It’s understandable that homeowners would want to protect their housing investment and maintain their neighborhood aesthetic, although some use those instincts as a cover to prevent the arrival of more racially diverse or economically diverse neighbors. In any case, that power is often a luxury. As Miller told me, middle- and lower-income areas typically don’t have covenants to regulate how residents want their neighborhoods to evolve. Thus, they face the most pressure from new development and cope with gentrification, while wealthier areas stay the same.

I thought of these various contradictions during a recent election in Kansas City, Missouri. Last November, more than 70 percent of voters approved a bond issue that will inject $50 million into an affordable housing trust fund. It was a massive success for several local politicians and the city’s housing activists, who helped amass citywide support. In some of Nichols’ Country Club District precincts, around 80 percent of voters approved the measure. But will much of the funding be granted for affordable housing in their neighborhoods? Doubtful.

The area is zoned to largely forbid townhomes and apartments. And if Kansas City ever overturned single-family zoning (as cities like Minneapolis have), restrictive covenants in many Country Club District neighborhoods binding the land to single-family usage could still block affordable apartments—covenants that Nichols signed some 100 years ago.

It might seem hyperbolic to trace the enduring appeal, and exclusionary character, of American suburbia to Nichols. But I believe that Nichols himself would agree with this view. In a profile published by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1925, Nichols argued that he and a coterie of influential developers would impact the country for generations to come.

“Cities are handmade,” he said. “And the men who build the city today are responsible for the heritage posterity receives.”