Manischewitz matzo, a staple of Passover, originated in Cincinnati

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Chalk up another everyday product with origins in Cincinnati, along with Ivory soap and Frank’s RedHot. Cincinnati matzo.

The most popular brand of matzo, the unleavened bread that is a staple food during the eight-day Passover holiday, is manufactured by the Manischewitz Co., which started in Cincinnati in 1888.

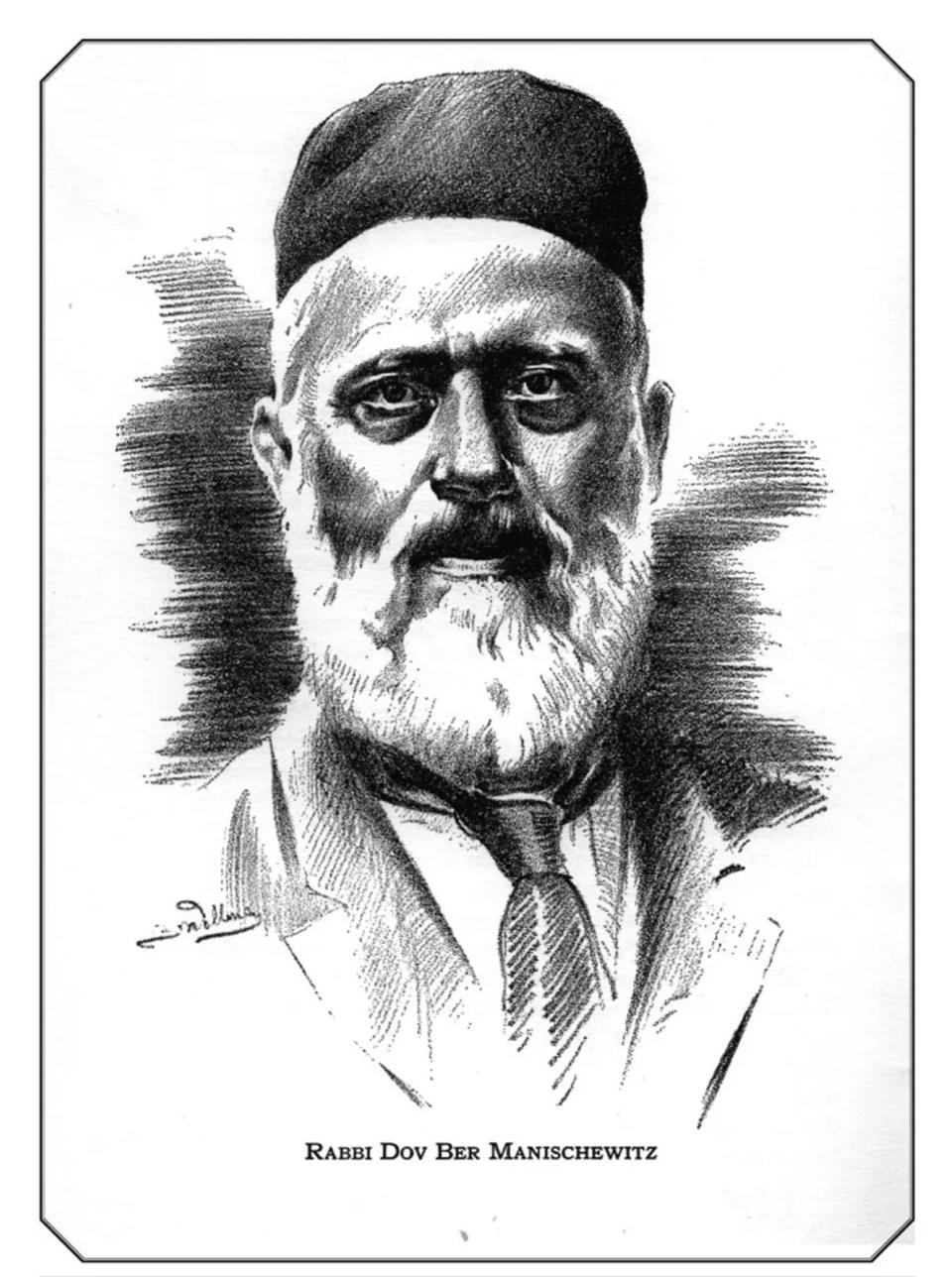

The founder, Rabbi Dov Behr Manischewitz, built up his little West End matzo bakery into the mass production of kosher Jewish foods. For a while, the cracker-like matzo consumed by Jews all over the world was synonymous with the Queen City.

Our Food Roots: How Cincinnati Jews changed how America ate

It’s rather ironic that the name Manischewitz is recognized across the globe because that wasn’t actually his real name. Behr Manischewitz was born with the surname Abramson around 1857 in Lithuania, then part of the Russian empire. It is uncertain why he bought the passport from a dead man named Manischewitz in order to emigrate to America in 1885, perhaps to escape conscription into the Russian army.

He settled in Cincinnati under his new name to work as a shochet, a ritual slaughterer, for the Beth Hamedrash Hagadol congregation of Orthodox Jews from Lithuania. Yet, he found few options for matzo for his Passover seder meal here, so he started his own matzo bakery on West Sixth Street.

Within a few years, the B. Manischewitz Co. expanded to more bakeries, on West Eighth and Clark streets. He also began using machinery to mass-produce matzo, which caused controversy about whether the machine-made matzo could adhere to the strict religious restrictions of Passover.

Machine-made matzo

The Jewish holiday of Passover commemorates the Israelites’ escape from slavery in Egypt, as told in the Bible. Because of their rapid departure, the Israelites had no yeast for their bread, so only unleavened bread is allowed during Passover.

Matzo (also spelled matzah) is made of flour and water that has not fermented or risen. Tradition has settled on 18 minutes as the time limit before dough begins to rise on its own and become chametz (leavened bread that is forbidden during Passover). Any residual dough cannot be folded into a new batch, because that portion would be older than 18 minutes, so all materials must be cleaned between each batch.

Manischewitz demonstrated the mechanized bakery’s adherence to the halakhah, the laws of Jewish life, as overseen by rabbis along the production line. The matzo was made in a square rather than the traditional round shape, so there was no worry of the trimmed edges being worked back into the dough. Manischewitz helped to support the next generation of rabbis, who viewed the machine-made matzo as acceptable, even preferred as cleaner because it was untouched by human hands.

This square Cincinnati matzo was soon copied everywhere, so Manischewitz began to push the name rather than Cincinnati in his marketing.

Manischewitz died in 1914 and is buried in the Beth Hamedrash Hagodol cemetery in Covedale. His will stipulated that his five sons take over the company, but that 1/10th of company profits go to charity in Jerusalem and locally.

In 1932, the company built a new factory in New Jersey, closer to a larger Jewish population, and moved the headquarters there in the 1950s. The Cincinnati factory on West Eighth Street closed in 1958.

The company also diversified to other kosher products, including Tam Tams crackers and gefilte fish, and licensed the name to a kosher Concord grape wine (with the famous catchphrase “Man, Oh Manischewitz”).

The family sold the B. Manischewitz Co. to Kohlberg & Co. for $42.5 million in 1990, when it controlled 80% of the matzo market, according to CNN Money. After 134 years, Manischewitz is still the name in kosher foods for Passover.

Sources: “Manischewitz: The Matzo Family” by Laura Manischewitz Alpern, “The Americanization of Matzo” by Rabbi Bruce Kahn, Cincinnati Magazine, Chabad.org, Wikipedia, Enquirer, Post and American Israelite archives.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Manischewitz matzo, a staple of Passover, originated in Cincinnati