‘So many flaws.’ Broken bones, abuse and isolation inside Kentucky juvenile lockups.

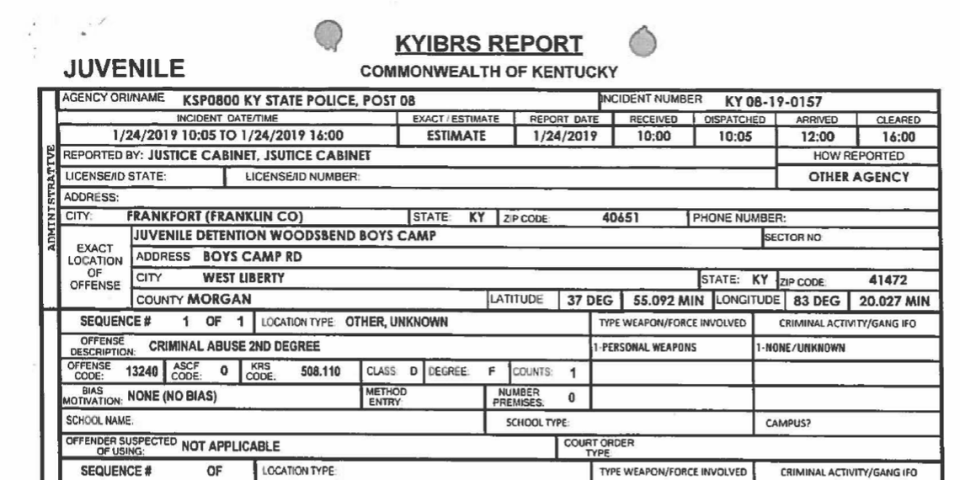

By the time youth worker Nathaniel Lumpkins got fired from the Kentucky Department of Juvenile Justice in 2019 for interrupting a time-out situation that two of his colleagues were handling and breaking the bones in a teenager’s left wrist, he already had a history of problems.

Disciplinary records show that in the previous six months, the department twice cited Lumpkins for using “excessive force” instead of the nonviolent restraint techniques required of employees at the Woodsbend Youth Development Center in Morgan County.

Once, he grabbed a youth’s neck while repeatedly pushing his open hand into the youth’s face. Another time, he dropped his knees onto a juvenile’s left arm while painfully twisting the wrist. The latter incident drew Lumpkins a one-day suspension. At the bottom of the suspension letter, he hand-wrote, “I maintain my innocence.”

Kentucky State Police eventually would investigate Lumpkins for possible criminal abuse charges, although the Morgan County grand jury declined to indict him. But co-workers grew wary. Lumpkins sometimes was “tapped out” — tapped on his shoulder and ordered to exit a group restraint of a youth — because he got angry.

“We try to keep him out of situations as much as possible,” another youth worker, Gary Johnson, explained to the department’s internal investigators after the face-shoving episode. A supervisor, Sam Wells, said he was frustrated with Lumpkins, whose decision-making he described as “horrible” and “haphazard.”

Yet Lumpkins remained on the payroll until he was terminated more than a month after the third incident.

(A man who recently answered the phone at Lumpkins’ home refused to give his name, and he would not comment on Lumpkins’ time as a youth worker. “From our experience, I think the media would be biased against us on this,” he said.)

The Department of Juvenile Justice runs two dozen residential facilities around Kentucky that on any given day house roughly 235 youths, age 12 to 18, who are awaiting a court appearance or serving sentences. It also monitors roughly 450 youths on community supervision. Nearly 990 people work for it.

What the department doesn’t always do — as evidenced by the teenager’s fractured wrist in Morgan County — is protect the kids in its care from the adults who are paid to guard them.

“I’ll be honest. If they just had people come in at random — like on a random day, unannounced — and they did a thorough investigation of that place, I’d be surprised if they found it operational,” said Jezreel Bell, who spent more than two years as a youth worker at the Warren Regional Juvenile Detention Center in Bowling Green.

Bell quit in early September. He said he became demoralized by chronic under-staffing and inadequate training and support that put everyone inside the facility at risk.

“There are so many flaws,” Bell said. “The kids aren’t getting anything out of it. All we are doing is quite literally keeping them in a cell and praying for the best, watching the clock and hoping nothing happens until your shift ends and you get to get out of the building.”

116 incidents in three years

The Herald-Leader reviewed thousands of pages of department records, state personnel files, police reports and other documents and identified at least 116 substantiated “special incidents” involving the department’s employees from February 2018 to May 2021.

The majority of these incidents involved youth workers — the title the department gives to security guards — using force on juveniles that was determined to be excessive by the agency’s Internal Investigations Branch.

Typically in these cases, employees were trying to restrain a youth who refused to comply with their orders or who otherwise ran afoul of facility rules.

Juvenile justice employees are taught to restrain youths with Aikido Control Training, which uses joint locks and circular movements to control an opponent instead of the usual kicks and punches seen in martial arts.

Even that is not without controversy. Kentucky public school districts banned the use of Aikido against students in 2016 over concerns that it led to serious injuries.

The excessive force incidents ranged from relatively minor violations by department standards, such as putting youths in headlocks or throwing them down to the ground, to more serious fights that sent injured youths to the hospital.

In 2018, a youth who brought his shoes into his room against orders got kneed in the back by youth worker supervisor Brent Kimbler while lying face-down on the floor during a restraint at the Adair Youth Development Center in Columbia. Kimbler told investigators he “may have” put his knee into the youth’s back, but only to keep him from rolling over and hurting staff members.

Youths are not supposed to be restrained for failure to surrender personal items, like their shoes, investigators wrote in a report on the incident. And Aikido training materials provided to the Herald-Leader by the department indicate that employees are not supposed to put their knees into a youth’s back.

Kimbler earlier was named as one of the defendants in a 2016 lawsuit against the department after a teenage girl died while in isolation at a juvenile detention facility. He was suspended for 10 days for “poor work performance and misconduct” for failing to conduct required bed checks in that case.

Then he returned to duty.

Kimbler is still employed by the department, now at its London Group Home. He told the Herald-Leader that his supervisors instructed him not to comment about past incidents in which he was involved.

In another incident, in 2020, youth worker Jeremy Baker wrapped his arm around a 17-year-old resident’s neck and dropped him to the floor during a restraint in the intake area at the Fayette Regional Juvenile Detention Center in Lexington. The youth hit his head on a box during the tackle.

“Told you not to try me, n--ga,” Baker told the teen, who is Black, according to the report written by internal investigators who reviewed audio of the incident. “You going to prison, n----r.”

Baker — whose previous job was loading delivery trucks for Pepsi — was suspended for 12 days. But months after the incident, the department gave him a pay raise, bumping him from $34,728 to $36,465, according to personnel records.

He still worked there this summer. Speaking briefly by phone with the Herald-Leader, he said, “I don’t want to talk about it (the incident report). Whatever they put down on there, I’m good with it.”

Nobody told the teen’s family about the incident until the Herald-Leader contacted them this summer.

“It’s ridiculous that nobody reached out to us. When stuff like that happens, they need to get in touch with the families so we know about it,” said Pamela Sykes of Lexington, who is the teen’s aunt.

The juveniles at the detention center are reluctant to blow the whistle on staff, she added.

“A lot of times, they don’t say anything out of fear nobody will believe them, they’ll believe the grownups,” Sykes said. “And it will just make their stay harder if they get the staff mad at them.”

Watching riots happen

Records show that apart from excessive force, employees engaged in inappropriate sexual conduct with youths; used racial slurs and threats of violence; and failed to provide appropriate supervision, which sometimes led to illegal drugs being smuggled into facilities, youth-on-youth sexual assault and destructive riots requiring police intervention.

“F--k this place!” youth worker Matthew Land snapped on June 13, 2020. Land and a half-dozen colleagues abandoned a housing unit in the maximum/medium-security McCracken Regional Juvenile Detention Center in Paducah while some of the youths inside seized control and trashed it.

The rioting youths had plucked the security keys off an employee’s belt.

The shift supervisor disappeared. He later said he went searching for reinforcements. One staff member explained to investigators that “she did not know what she was doing, nor did other staff know what to do,” according to a department report.

The youth workers munched on graham crackers and looked in at the chaos through the windows, investigators wrote. “Staff watched residents destroy the inside of the units,” they wrote.

Kentucky State Police restored order at the facility two hours later. They found one youth hiding inside who did not participate in the riot, left behind by the staff to fend for himself.

By then, Land was long gone. He ended his shift 90 minutes early that day and drove home. He told investigators that he “pretty much lost it.”

This system-wide security failure wasn’t unprecedented for the Paducah facility.

The same thing happened there three weeks earlier.

Feeling outmatched by a single rampaging teenage girl whose door they carelessly left open at bedtime, several fleeing employees abandoned a housing unit on May 26, 2020, and left four other youths trapped inside. Paducah police arrived two hours later to take command.

The staff members “lost confidence” in their ability to control the situation, investigators wrote in their report. Some complained of assorted medical ailments they said would prevent them from confronting the girl. They left her alone inside to flip furniture, ram doors with tables and destroy property.

Fifth commissioner since 2018

The Department of Juvenile Justice refused the Herald-Leader’s request under the Open Records Act for video and audio recordings it holds of many of these incidents, citing security and privacy concerns.

It also refused the newspaper’s repeated requests to interview officials at the department and its parent agency, the Kentucky Justice and Public Safety Cabinet, to discuss the documented incidents or answer questions about the safety of juveniles in state custody.

Gov. Andy Beshear’s administration earlier this year fired Juvenile Justice Commissioner LaShana Harris for what it described as “unsatisfactory performance of duties.”

It replaced her with Vicki Reed, the fifth person to hold the job since 2018.

“They’ve gotten a new commissioner every year, it seems. If you think of how a statewide institution is supposed to be uniformly organized and engaged, it can’t help when the people at the top keep changing all the time,” said Amanda Mullins Bear, managing attorney for an advocacy group, the Children’s Law Center in Lexington.

The newest commissioner comes from a reform background.

Working inside and outside Kentucky state government over her career, Reed has pushed for improvements in how juveniles are treated by the courts. Last year, she published The Car Thief, a sympathetic novel she wrote about a homeless adolescent boy swept up in the child welfare bureaucracy and penal system.

In a prepared statement for the Herald-Leader, Reed said she will visit the department’s residential facilities with an eye on the safety of residents and staff, and she will lead an examination into the department’s use of restraints and isolation.

“I hope that one day all of Kentucky’s youth have a strong family support system, access to excellent education and workforce development to empower them to make good decisions and avoid the juvenile justice system altogether,” Reed said in her statement.

“Until then, I will strive to build our youth up and provide a solid foundation for their future, while also tackling any emotional, physical and mental needs relating to experiences or traumas from their past,” Reed said.

Employees’ second chances

Records show that some department employees are cited for “special incidents” with youths multiple times, and when they are disciplined, it can be done inconsistently. Some are fired while others are allowed to resign on their own terms. Some are kept on even after the kinds of incidents that have cost others their jobs.

For example: In two separate incidents this year, male youth workers Thomas Langston and Jeffrey Overstreet observed nude girls in the showers despite the girls’ protests and in violation of policy, internal inspectors wrote.

Langston was allowed to resign over his incident several months later, personnel records show. Overstreet remained on the job as of August, although he received a “verbal warning,” according to state records. It wasn’t clear from state records why the two cases were treated differently.

Or: Youth worker Gregory Saylor Jr. drew a 10-day suspension in 2011 for phoning in a bomb threat to the Northern Kentucky Youth Development Center in Kenton County, where he worked. The facility went into lock-down mode and called police for help.

The department described the bomb threat as “an inappropriate joke” in its disciplinary letter to Saylor. However, the next year, it promoted him to youth worker supervisor, putting him in charge of his colleagues.

In 2019, the department cited Saylor and others for pinning a boy’s leg in the doorway of a room for three hours by bracing the heavy steel door against the boy’s leg. For good measure, Saylor pressed forcefully against the door several times with his hands, according to records.

Later, the boy was left in handcuffs and leg chains overnight and locked in isolation for more than 43 hours, in violation of the department’s limits on how long isolation can be used.

An orthopedic specialist afterward diagnosed the youth with neuropraxia, or mild nerve damage, as a result of the injuries he suffered that day.

The initial complaint that led to the youth’s punishment? He was “wearing his pants halfway down,” according to department records.

The department tried to fire Saylor for the incident five months later, but he appealed to the Kentucky Personnel Board. He and the department negotiated a deal that allowed him to resign and have the dismissal letter removed from his personnel file.

And in 2018, a year before Lumpkins got fired for breaking a boy’s wrist, a counselor named Narrasheod “Leon” Perryman broke the left wrist of a different boy by forcefully bending it after tackling him during a restraint at the Fayette Regional Juvenile Detention Center, according to investigators.

Perryman, who weighed 260 pounds — more than twice what the boy weighed — told investigators that he was on blood-thinning medication and worried about getting hurt during the restraint, but he did not intend to overreact by breaking the youth’s wrist.

Speaking to the Herald-Leader, Perryman said he used an approved Aikido Control Technique on the boy that ended with bone fractures.

“What I used, it’s a technique we use quite often, and it’s unfortunate, but you know, sometimes injuries have resulted from that,” he said. “Kids who are 14, 15 years old, a certain age or a certain size kid — it’s happened four or five times to my knowledge.”

Lexington police and the Fayette County attorney investigated the incident for assault charges, according to department records. Perryman said he was tried in Fayette District Court and found not guilty. He had his court records expunged, he said.

There is no record of disciplinary action related to the incident in Perryman’s personnel file. He stayed on for two more years, resigning in November 2020.

It can be difficult to fire a state employee with merit-system protection, said Ray DeBolt, who served briefly as juvenile justice commissioner under former Gov. Matt Bevin in 2019.

“They are basically civil-service workers with the right to appeal our decisions to the Personnel Board,” DeBolt said. “So it has to be something that’s pretty egregious. We’ve had to take people back on until there have been sufficient documented grounds to terminate them.”

In a prepared statement, the Department of Juvenile Justice said it takes allegations of mistreatment seriously, which is why it has an Internal Investigations Branch.

“DJJ leadership encourages youth and staff to report any issues or concerns they witness or experience. The facilities’ superintendents review all incidents and corresponding videos and report any occurrences which they have determined to have potentially violated the department’s policies and procedures,” the agency said.

“Upon completion of an investigation, if the allegation or complaint is substantiated, staff may be subject to a personnel action which ranges from a written reprimand up to termination, depending on the nature and severity of the matter. Staff may also be required to complete additional training to prevent any future issues.“

‘Under-staffed big-time’

Perryman said his colleagues had a hard job. They had to be ready at a moment’s notice to step in and stop teenagers who can be as strong and as fast as them and possibly as skilled at fighting, if not more, he said.

“In all the restraints I was involved in over 15 years, I never had one go by the textbook,” Perryman said. “The kids there don’t attack you the way you’re taught in the classroom. You can train and have the best-laid plans, you can have your Aikido ready, but the way it really goes down, somebody is going to get hurt.”

“What you’re trying to do is keep that down as much as possible,” he added. “Folks on the outside don’t necessarily understand how it works on the inside. It can be pretty rough. What looks like an excessive amount of force can, in fact, be necessary if you know the facts of what happened.”

The department fired youth worker supervisor Roscoe Echols after he was cited twice in 2019 for using excessive force on juveniles at the Green River Youth Development Center in Butler County. He has a wrongful termination lawsuit pending against the department in which he claims he was unfairly targeted by internal investigators who overlooked violations involving some of his co-workers.

Speaking to the Herald-Leader, Echols said the residential facilities are “under-staffed big-time,” creating dangerous situations for everyone involved.

The department’s Aikido training might look good on paper, but it’s not realistic for youth workers when they are badly outnumbered, he said. That’s why restraints can turn into ugly brawls where people get hurt, he said.

“When something happens — and something’s always gonna happen — there aren’t enough staff on the floor to properly respond to it and contain it,” Echols said.

“On a typical day, if a facility had 30 youths, they might have four staff members working a single shift,” he said. “During the end of my time there, I can tell you, we had three riots, but we kept it from getting out. We had three riots just within the span of four months. That doesn’t even count the number of staff getting assaulted. I got kicked in the face by a steel-toed boot.”

A March 2018 policy memo issued by the department set a daytime juvenile-to-staff ratio of no more than 8-to-1.

But recent inspections of the residential facilities by the American Correctional Association showed that’s often a missed target. For example, the group’s auditors noted a 10-to-1 ratio at the Northern Kentucky Youth Development Center in Kenton County, with 19 youth workers assigned to watch 32 juveniles in three daily shifts across four living units. The facility made heavy use of isolation rooms and psychotropic medication, the auditors observed.

And in Lexington, auditors reported 44 youth workers assigned to watch an equal number of juveniles at the Fayette Regional Juvenile Detention Center, but spread across three daily shifts and multiple housing units.

“Staffing continues to be a problem,” the auditors wrote of the Lexington facility. They noted 63 resident-on-resident assaults inside the facility in recent months — “a significant number.”

The department recruits blue-collar workers with high school diplomas and starts them in the low $30,000s, according to personnel records. Given how hard the job can be, retaining enough good people at that wage is a constant challenge, said DeBolt, the former juvenile justice commissioner.

“There are specific regulations that say what our staffing ratios are supposed to be at the facilities, and we routinely violated them,” DeBolt said.

In a statement prepared for the Herald-Leader, the department said it “has attempted to reduce staff vacancy rates” by adding new employment incentives. It sweetened the state retirement benefits for youth workers by changing their job classification from non-hazardous to hazardous. Hazardous-duty workers get to retire years earlier.

Additionally, in 2017, Bevin agreed to give a 20 percent pay raise to new juvenile justice employees — a rarity in state government. Bevin felt compelled: The year before, the department hired 151 people while losing 180.

A kid’s fractured wrist

An 18-year-old from Louisville refused to “take a chair” — sit quietly as ordered for a penalty time-out — on Jan. 23, 2019, at the Woodsbend Youth Development Center, a medium-security facility for boys in a remote wooded area of Morgan County.

The teen had just gotten a phone call from back home about his uncle’s deteriorating heart condition. He was upset and wanted to talk to a counselor.

Two youth workers, Gary Johnson and Jerrod Hillman, walked behind the teen and tried to calm him. He was “a good kid,” so Johnson figured the situation probably could be resolved without confrontation, Johnson later told the department’s internal investigators. Several residents sat on a nearby couch.

The men heard the heavy tread of footsteps getting louder.

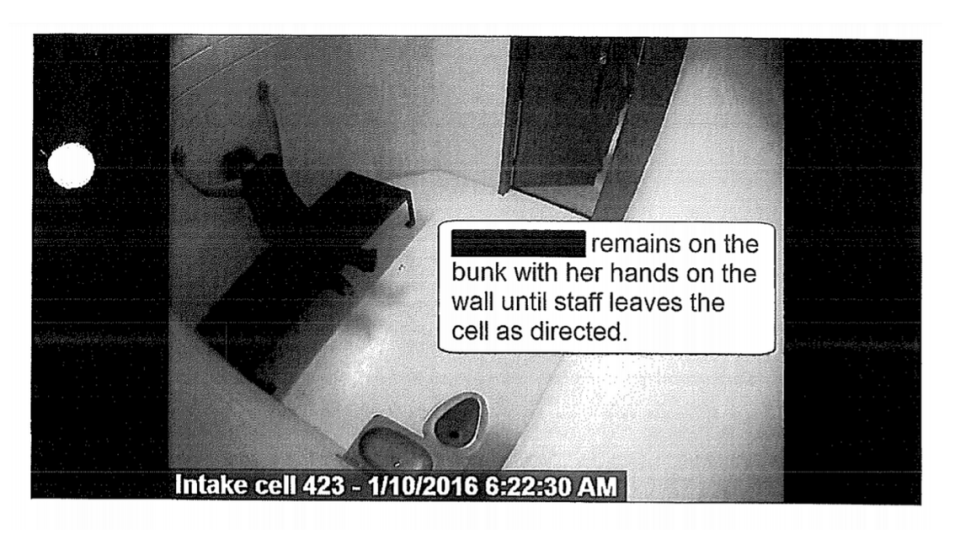

Security video showed a third youth worker, Nathaniel Lumpkins, run into the room, move between Johnson and Hillman and grab the juvenile by his right shoulder. Lumpkins, a former corrections officer at the nearby state prison, had been cited twice in six months for excessive use of force with juveniles at the facility.

Within moments, the juvenile was struggling with all three men. Lumpkins fell to the floor twice, bringing the youth down with him. A youth worker supervisor, Justin Leach, jumped in. Now, four men were grabbing for different parts of the teenager in order to restrain him.

The department’s written summary of the security video footage describes what happened over the next several minutes :

“Lumpkins applies pressure causing (the juvenile’s) left arm to buckle at the elbow ... Lumpkins continues to apply downward pressure to (his) left wrist ... Lumpkins applies more downward pressure to (his) left wrist again causing his arm to buckle at the elbow ... Lumpkins pulls (him) from the floor by his left wrist ... Lumpkins begans to slam (his) left hand/wrist on the wall.”

The juvenile himself, speaking afterward to a Kentucky State Police detective, provided this description: “Mr. Lumpkins, he had grabbed my arm. He started bending it and twisting it and pulling my skin.”

“I was like, ‘Why are you pullin’ my skin?’ He ain’t sayin’ nothing, he just kept going. That’s when he stood up on his feet. He put all of his weight, his force on my wrist and everybody heard it crack. Everybody was like, ‘You just broke his arm! Get off him!’ But he wouldn’t get off. He just kept on going, putting on more and more force, and he was calling me ‘boy.’ I took offense to that because my name is not ‘boy.’”

The youth said he spent two hours in isolation, crying and asking through the door for medical treatment for his throbbing wrist. Once he was taken to the hospital, doctors identified fractures in the youth’s radius and ulna, the bones in his forearm, near his left wrist. This is called a “buckle fracture.” They set the broken bones in a cast.

Back at the residential facility, Lumpkins would only give part of an interview to investigators looking into the incident before he cut them off and left the room. He referred all further questions to his lawyer.

During the comments he did make, Lumpkins said he felt “awful” the youth got hurt, but he denied intentionally harming him or calling him “boy.” He blamed his colleagues for putting him “in this situation” by doing a sloppy job of controlling the youth, which he said required him to forcefully intervene.

The department fired Lumpkins on Feb. 27, 2019.

Leach, the supervisor, told investigators that learning about the youth’s broken wrist made him “sick to my stomach.”

After reviewing video footage, Leach said it appeared Johnson and Hillman had the situation under control, so Lumpkins erred by running in. Leach added that toward the end of the encounter, he had to tell Lumpkins to leave the isolation room because Lumpkins was shouting closely into the youth’s face.

Speaking to a state police detective, Johnson agreed with his boss. Lumpkins didn’t need to charge in, he said.

“I wasn’t comfortable at this time because my thought was, we had compliance. We absolutely had compliance at this point. There was no reason to go further,” Johnson told the detective. “I thought we could talk him down.”

The detective asked Johnson if the violence that day was necessary “to basically maintain control for the youth’s safety?”

“I can’t in good conscience say that,” Johnson replied.

‘He just lost it.’ A sample of abuse cases from KY juvenile detention centers.

‘Set up for failure.’ KY youth worker claims pressure to water down incident report.

The story of the KY Department of Juvenile Justice is a cycle of scandals & lawsuits