Many Native Americans consider Thanksgiving a day of mourning. Here’s how they mark the day

When hundreds of people gather on Cole's Hill above Plymouth Rock in Massachusetts on Thursday, it will not be in celebration of Thanksgiving.

Members from numerous Indigenous communities as well as non-Natives will instead come together for the annual National Day of Mourning to mark the historical atrocities against Native Americans that often get lost in the traditional telling of Thanksgiving.

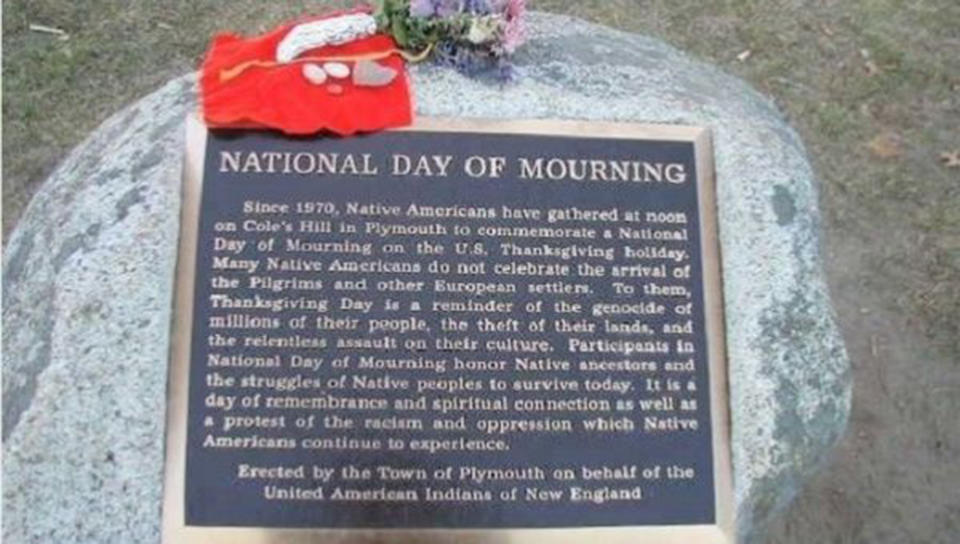

The live-streamed ceremony, which is organized by the United American Indians of New England, first started in 1970 with the goal of bringing awareness to the genocide of Native Americans and theft of their lands while aiming to promote the facts behind the Thanksgiving holiday.

"The myth that most of us grew up with in school is that Pilgrims were seeking religious freedom, landed on Plymouth Rock, and then the Pilgrims and Indians sat down for a harvest meal together, and then the Indians just faded into the background and somehow everyone lived happily ever after," UAINE co-leader Mahtowin Munro told TODAY. "In our view, this is a lie to hide the genocide of Indigenous peoples."

The traditional story involves the Pilgrims and Wampanoag people coming together in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1621 to share a meal. However, according to Munro, Thanksgiving feasts in the 1630s were often held to celebrate settlers' military victories over Native Americans.

"I think a real shocker that a lot of people don’t know about is that although there was a harvest-time meal in 1621, that was not ever called 'Thanksgiving' in any way, shape or form," said Munro, who is a member of the Lakota.

"The first Thanksgiving proclaimed by the settlers was in 1637 by the governor to celebrate the massacre of 700 Pequot men, women and children."

Thanksgiving is the latest difficult holiday for many Indigenous communities in a fall season that is full of them, according to Munro.

For the first time this year, the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation and Orange Shirt Day were declared on Sept. 30 in Canada to mark the lost children and survivors who were taken from their families and placed in 140 federally-run Indian residential schools between 1831 and 1998.

"People were coming out from all over to honor the children who died at the residential and boarding schools, and insist their remains be located, identified and returned to their communities," Munro said.

That was followed by Columbus Day on Oct. 11, which has also become the date of a separate celebration of Indigenous People's Day. Columbus Day is seen by many as a celebration of Italian American heritage, while Indigenous communities see it as a celebration of a figure whose explorations contributed to genocide, colonization, the slave trade and millions of deaths of Indigenous people.

"We're having to combat the idea of Columbus as a hero as an ongoing thing every year," Munro said.

That day is followed by Halloween, when many non-Native people "dress up in offensive Indian costumes," Munro said. Then there is Thanksgiving this month.

“One common thread for all of these observances are Indigenous peoples being centered, telling their truths and going forward promoting our view of what really happened here in North America,” Jean-Luc Pierite, a member of the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana and president of the board of directors of the North American Indian Center of Boston, told TODAY.

"I know that for non-Native people, Thanksgiving can seem like a fun holiday where you get together with family and eat turkey," Munro said. "Sometimes we're asked why we don't give thanks, but Indigenous people give thanks many times a day. Why would we be thankful for the arrival of European invaders?"

The first National Day of Mourning happened in 1970 when Wampanoag leader Wamsutta Frank James started it after he was uninvited to speak at a dinner that was supposed to celebrate the 350th anniversary of the Pilgrims' landing at Plymouth Rock.

A plaque on Cole Hill details the annual day, which has often featured a potluck and traditional dances before some of the activities had to be curtailed due to the coronavirus pandemic.

The National Day of Mourning can also serve as an educational opportunity for Indigenous youth in what can be a confusing time for kids who may be taught two different traditions between school and home when it comes to Thanksgiving.

"From a very early age we are always walking in two worlds," Pierite said. "We have our children in public schools who hear stories about Christopher Columbus and Thanksgiving. We do have families that come into our urban Indian center and tell us stories about how their children are disproportionately disciplined in their schools for standing up to teachers and saying, 'What you’re telling me in history books is not what my family is telling me.'"

The National Day of Mourning is also not just about looking back in history, but also speaking about current issues facing Indigenous communities.

"A lot of non-Native people seem to think we’re stuck in the past or that we don’t exist any more, so it’s really important talking about a lot of contemporary issues as well," Munro said.

Issues that will be discussed by speakers at the National Day of Mourning include the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women, the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Indigenous communities, the fight to bring home the remains of children from residential schools, the need for Indigenous voices and stewardship to deal with climate change, and the struggles to stop pipelines and mining projects on Native American lands.

"It's a really powerful day," Munro said. "It’s a beautiful day of unity, and it’s great to have a space for people to listen and learn from Indigenous peoples. It's something that’s not happening enough."

It also is a day to show the vibrancy of Indigenous communities, particularly in New England.

"I think there’s a resurgence in being proud in being Native American," Pierite said.