Many NC Confederate monuments are falling fast. But their divisive legacies linger.

In thousands of towns throughout the South, the old markers of racial segregation — separate public water fountains marked “Colored” or “White,” side entrances at the theater, divided waiting rooms in the doctor’s office — are long gone except for in the memories of people such as Chris Neal, who lived those ignominies well into his teenage years.

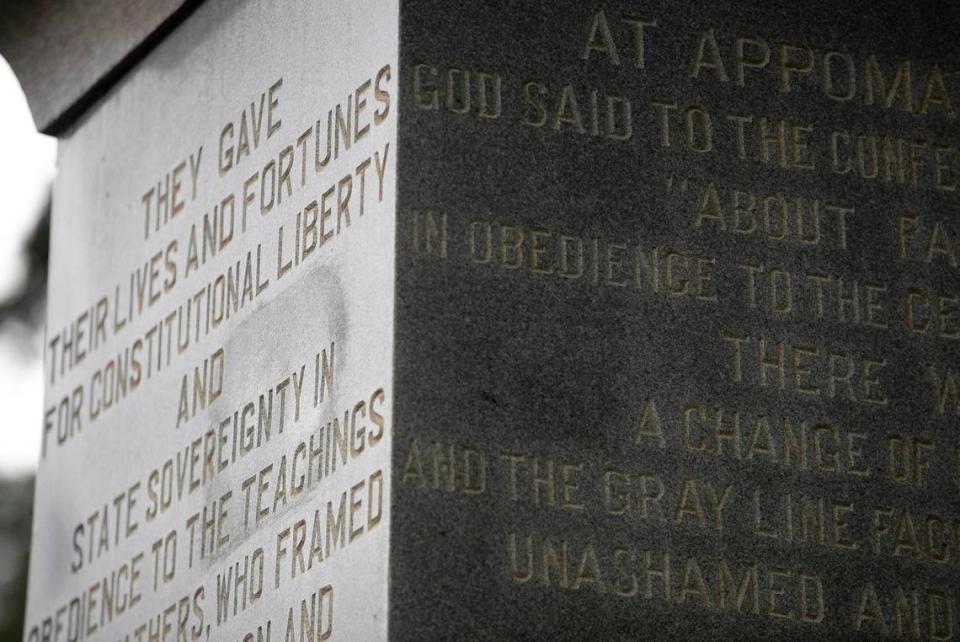

But one relic, forged of bronze and set in stone, remains perched on the highest hill of one of the busiest streets in Louisburg, a stubborn reminder that not so many generations ago, Neal’s ancestors would have been under the complete dominion of those of his white neighbors. Treated as inhuman. Disenfranchised. Enslaved.

At least, that’s what Louisburg’s “Monument to Our Confederate Soldiers” means to him.

“That statue is very divisive,” said Neal, a member of the Louisburg Town Council who voted this week to relocate the monument from its grassy island in the middle of Main Street to a nearby city-owned cemetery where veterans of the Civil War are buried.

Larry Norman, an attorney in town and a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, has filed a motion seeking an injunction against the move. As evening falls, a contingent of monument supporters stakes out the statue, in case a crane comes in the night to spirit the soldier away.

Across North Carolina, those who regard monuments to the Confederacy as “heritage, not hate,” are aggrieved over the removal, whether by vote or by violence, of a growing number of them.

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, there were monuments to the Confederacy in at least 140 public spaces in North Carolina in 2016. Most were commissioned by local chapters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which raised the money and often chose the monuments from catalogs produced by Northern foundries.

Most of the monuments were installed at times when Southern states were resisting efforts by Black residents to get political power and civil rights. They were especially popular during the late 1800s and early 1900s, when white Democrats dominated legislatures in Southern states and enacted Jim Crow Laws.

Monuments coming down

After standing for decades, at least nine of the monuments in North Carolina have been taken down or are slated to be, including the one in Louisburg.

First there was “The Boys Who Wore The Gray,” which stood outside the old Durham County Courthouse until protesters ripped it down, badly damaging it, in August 2017.

“Silent Sam,” which stood near Franklin Street and memorialized those who served in the Civil War from UNC-Chapel Hill, was pulled down by protesters in August 2018.

In March 2019, the monument to “Our Confederate Dead” that had been installed in 1905 at the old Forsyth County Courthouse with a dedication speech by white supremacist Alfred Waddell was ordered removed to prevent its becomig a public nuisance.

The stamped-copper statue honoring “our Confederate Heroes” from Chatham County was removed last November after a vote by the board of county commissioners. It had stood sentinel outside the old county courthouse since 1907.

This year, the pace has accelerated due to protests that have followed the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis after an officer held his knee against Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes.

The statue of the muse Fame, honoring Salisbury’s Confederate dead, will be moved to the Old Lutheran Cemetery in town after a vote by the Salisbury City Council earlier this month.

Buncombe County officials voted this month to remove the Zebulon Vance Monument from Pack Square Park in Asheville, and the Asheville City Council voted to take down a Confederate soldiers’ monument on the courthouse grounds and a plaque honoring Robert E. Lee that stands near the Vance Monument.

The 75-foot tall monument “To Our Confederate Dead” that stood outside the N.C. State Capitol in Raleigh was removed Sunday night on orders of Gov. Roy Cooper after protesters tore down companion pieces mounted to the same base.

Granville County’s monument “To Our Confederate Dead,” erected in 1909 outside the courthouse in Oxford and moved to a library after racial unrest in 1971, was taken down and put in storage this week.

Opposition to the monuments has ebbed and flowed as well.

Some statues were vandalized or targeted for removal during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. They came under scrutiny again after a white man shot and killed nine Black members of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, S.C., in June 2015. And they became a flashpoint again in August 2017 after white nationalists rallied around a statue of Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, Va., that was scheduled to be moved, and one of the white supremacists drove his car into a group of counter-protesters, killing a woman.

What we ‘pay tribute to’

The protests following George Floyd’s death have lent a greater urgency to vandals’ efforts to destroy and officials’ push to peacefully remove Confederate monuments. Protesters complaining about police brutality against Blacks and about systemic racism in American society see the monuments’ century-long stances on public lands as government endorsement of white supremacist attitudes that have survived emancipation, the Civil War and decades of racial equity work.

“The things we make monuments to are things we want to pay tribute to,” said Juanita Moore, a member of the state’s African American Heritage Commission, charged with examining ways to diversify the memorials on the State Capitol grounds. A native of Wilson, Moore lived across the nation working as a museum curator and director before returning to North Carolina.

Unlike artifacts and exhibits in museums that are designed to educate in a neutral context, monuments are typically presented without objective historical fact.

“Monuments are not there to teach history,” Moore said in a phone interview with The News & Observer. “They are there to show the level of significance, and of importance, and of power of that person, or that idea or that concept. The monument is honoring it. It is not a teaching moment.

“So as an African American person, when I think about these Confederate statues, I have to ask, ‘Why were they placed there? Was it because this person, who committed treason and enslaved or helped to enslave other people, did some really good things? Or was it because of their involvement in the Civil War and their fight to preserve slavery?’

“That’s why those monuments were there,” Moore said. “They weren’t there to talk about the broader scope of this person’s life.”

Fears of destroying history

Norman, the attorney trying to stop the relocation of the Louisburg monument, said in an interview that he is opposed to the town council’s decision on two grounds. He believes the council was disingenuous in calling an emergency meeting to vote on moving the statue when it said it felt the monument was threatened in light of vandalism at other sites. And he believes the town’s plan to move the statue is illegal under the 2015 law signed by former Republican Gov. Pat McCrory that bars removing, relocating or altering monuments, memorials, plaques and other markers on public property without permission from the state Historical Commission except in certain circumstances.

Two of Norman’s great-grandfathers and two great-great-grandfathers were “on the right side” of the Civil War, he said. The walls of his law office are covered in portraits of Confederate generals.

“My personal opinion is, that statue needs to stay where it is,” he said. “It hasn’t hurt anybody in 106 years. It memorializes men who fought to save the South and fought to save sovereignty. They sacrificed a lot to protect their homeland.”

Frank Powell of Wake Forest, spokesman for the N.C. Sons of Confederate Veterans, whose members have protested the removal or relocation of Confederate monuments, said allowing the threat of violence or vandalism to justify removing century-old monuments amounts to mob rule.

“If we don’t follow the law,” he said, “we’re no better than third-world countries.”

Like some others, Powell said he believes that destroying Confederate statues is an early step in a deliberate process by Marxist, Socialist or Communist followers whose ultimate goal is to erase the material symbols of all kinds of American political and religious history. Recently, he noted, vandals have attacked monuments to George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Christopher Columbus, Abraham Lincoln, Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and two Catholic saints.

“It’s our entire history and our entire culture that are under attack,” Powell said. “Some of these people want to destroy it all.”

Moore, the former curator, disagrees.

“It’s not that people are trying to destroy history,” she said. “Folks get that wrong. There is a Museum of the Confederacy [in Richmond, Va.] and no one is saying, ‘Burn down the Museum of the Confederacy.’

“I am not one for destroying history at all. But there are all kinds of ways to learn. And you don’t start to teach history by making people feel like they are nothing, and that you are somebody because you enslaved other people. Or that only when there is someone who is not as good as me, then I’m somebody,” Moore said.

“And that is what we teach through racism.”