How many people does Kentucky need to put behind bars before we’re ‘safe?’ | Opinion

Picture this: You’re driving south of Lexington for a day trip to Nicholasville down in Jessamine County. Maybe you’re going to visit nearby Camp Nelson, or perhaps you’re there for the city’s Kentucky Wine and Vine Fest.

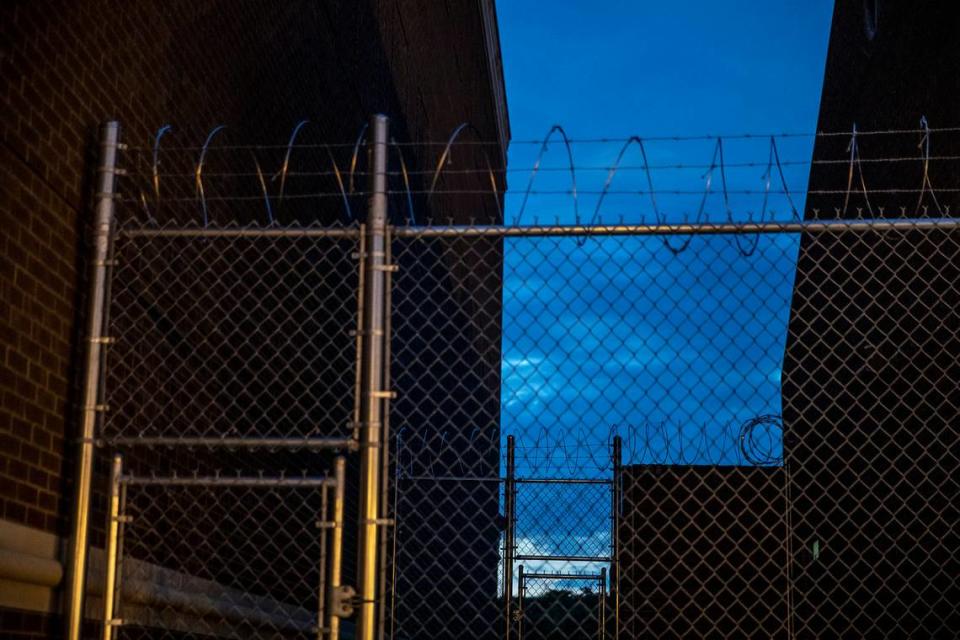

Now imagine that as you drive into the city limits what stands before you is a massive prison which encapsulates the entirety of the city and nearly all of its people.

A 2023 report from the Vera Institute of Justice found that in mid-2021, Kentucky had more than 20,000 people locked up in county and regional jails and more than 10,000 people were held in state prisons. The population of Nicholasville in mid-2021, per the U.S. Census Bureau, was just shy of over 31,000.

Almost an entire city’s worth of Kentuckians incarcerated in state prisons and local jails does not seem to be enough to deter our state’s lawmakers or convince them that the way we approach criminal justice is flawed.

There’s been a lot of momentum during the 2024 General Assembly to crack down on crime, get tough on crime, throw the book at criminals, that really boils down to one point and one point only: The majority of our state lawmakers want more people to be incarcerated.

The United States has the highest incarceration in the world; not in North America, not this side of the hemisphere but the entire globe. If Kentucky were a country, we would boast the world’s seventh-highest incarceration rate, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

Yet over the past few weeks I’ve continually heard from state lawmakers that we’ve actually been too soft on crime, too lenient with criminals.

Which is odd if you consider that from 1985 to 2018, Kentucky’s overall jail and prison population incarceration rate more than tripled, according to the Vera Institute study, from 382 to 1,320 people behind bars for every 100,000 working-age residents. If that’s the state being “soft on crime,” then I shudder to think what will happen once we really start cracking down.

The Safer Kentucky Act

The proverbial book our lawmakers mean to throw at criminals has taken the form of the Safer Kentucky Act, or House Bill 5. It’s a massive piece of legislation that would rework and revamp the state’s criminal code.

Part of the Safer Kentucky Act that’s gained the most attention is the provision of the bill that would criminalize homelessness in the state. Writ large just about the entirety of the legislation is chock full of things that have failed elsewhere (the three strikes law) or just asking for people to be killed (expanding shopkeeper’s privilege).

The bill would establish a new crime of “unlawful camping,” meaning police could charge people trying to sleep or camp in specified public and private spaces that are not designated for camping.

The solution to homelessness is not to throw people in jail and the actual people who stand the most to lose from this bill understand that.

Each and every one of us, myself included, are much more likely to end up personally bankrupt from some unexpected medical bill, or other tragedy, than we are to reaching the levels of immoral wealth gained by people by Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos.

What saves most of us in those kinds of situations is a safety net, a community of family or friends that helps us from falling through the cracks that some people unfortunately do not have or cannot access.

In this regard, the Kentucky General Assembly is just doing what any good political body does – criminalize poverty, capitalize on tragedy. And boy, are they just chomping at the bit to throw more people in jail.

Lexington is poised to become the second city in Kentucky to ban landlords from discriminating against people who use federal housing vouchers and alternative forms of payment to pay rent.

However, the General Assembly is looking to prohibit local governments from cities enacting that type of ordinance.

So if you’re a person who can only pay rent with a voucher, or other alternative payment, then you’d be out of luck if state lawmakers had their way. Suddenly you’re homeless.

What’s your next option? You were already strapped for cash to begin with. Well you have a car, OK, so at the very least you can sleep there. Bad news: the amended version of HB 5 lets you sleep there for 12 hours before you’re charged with the crime of unlawful camping.

Can you pay the fine? No? Maybe a stint in jail will help your problems? No? Too bad.

It all compounds, it all bleeds together.

Destroying what works

Now despite billions of dollars in the state’s rainy day fund we’re not going to adequately fund a lot of things that could help address public safety (housing and better paying jobs come to mind), but we are going to defund a statewide program that diverts criminal defendants to drug treatment instead of prison.

As Louisville Public Media reported, a last-minute amendment to the state budget passed by the House would defund the Alternative Sentencing Worker (ASW) Program. The program, housed with the Kentucky Department of Public Advocacy (DPA), works to get criminal defendants into substance abuse or mental health services for rehabilitation instead of incarceration.

A 2020 DPA report found during that fiscal year, ASW had nearly 3,000 alternative sentencing plans approved; saving the state a potential $39 million on incarceration costs. However it was perhaps too good at keeping people out of jail, so it has to go.

Even more ironic is the ASW program came about as part of what Kentucky sought to do in the last decade for criminal justice reform.

In 2011, the Kentucky General Assembly passed House Bill 463, The Public Safety and Offender Accountability Act. Back then the commonwealth faced the same problem we still haven’t solved: an inflating prison population.

The hope was HB 463 would decrease the state’s prison population, cut spending on corrections and expand access to treatment programs as a viable alternative to incarceration.

Thirteen years later, I think we can say that didn’t pan out. However, it’s not because the reforms we sought were not worthwhile, and not because they couldn’t work (the AWS program is proof it can work), but rather because when given the option between incarceration and treatment our base human instinct chose punishment over redemption.

The war Kentucky would come to wage on opioids in the intervening years would see the share of prosecutions with drug-related charges go from 15% of all prosecutions in 2011 to a quarter of all statewide prosecutions from 2018 to 2021, the Vera Institute found. These also increasingly become felony drug charges.

Likewise, the Vera Institute found that HB 463’s goal to expand treatment alternatives was undermined by “the preservation of broad prosecutorial and judicial discretion.”

While some state lawmakers may say our attempts at reforms failed I have to look at all of this and wonder, “Did we even really try?”

How many is enough?

If it’s not clear enough already, the state is willfully finding ways to throw more people into county jails and state prisons.

It’s worth asking, in the face of legislation that would not only incarcerate more people, but keep them incarcerated for longer: How many Kentuckians need to be imprisoned until we are safe?

What’s the number? Is it 50,000? Is it 100,000? Is it until we have enough to warrant that federal prison in Letcher County that U.S. Rep. Hal Rogers desperately wants?

Is it until local jails finally burst at the seams from their chronic overcrowding problems that harm both inmates and jail employees alike? What’s the game plan for those jails once there’s all these new inmates?

And if you want to talk brass tax, how much is the state willing to spend on this? Incarcerating people is no small amount of money.

An impact statement prepared by legislative analysts estimated the bill would bring a “significant increase in operational costs” for local and state governments, but no estimated total cost was included.

All of which is to say the full cost to taxpayers to fund what is essentially an exercise in futility is unknown at this time.

The Vera Institute report offers policy recommendations to Kentucky’s incarceration sweet tooth: reduce or eliminate criminal penalties related to poverty and drug use; investing in treatment for drug and alcohol use and mental health untethered from the legal system; eliminate revenue incentives that drive incarceration; overhaul the pretrial system, etc.

Our lawmakers will likely do none of that. Instead they will opt for the simple solution which is to lock more people away. God forbid we expect them to have the wherewithal to tackle hard problems and come up with solutions.

Homelessness is a problem in Kentucky, and it’s not exclusive to the big cities either; fentanyl and drug overdoses are a problem, and I’m not disputing that.

What I am disputing is that the solution to any of these problems is a one-size-fits all approach where we throw up our hands and go, “Well we haven’t really tried anything, so I guess jail it is.”

The decision to do so, in the face of other solutions, is an admission from our leaders that they are uninterested, and perhaps incapable, of tackling this issue and others.