So many videos have been presented in the Derek Chauvin murder trial. Will they help jurors reach a verdict?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Warning: This story contains images that viewers may find disturbing.

Before the trial of former Minneapolis police office Derek Chauvin began, many Americans believed he caused George Floyd’s death by kneeling on his neck for more than nine minutes.

Why? Because they’d seen at least part of a cellphone video taken by a bystander that appeared to show Chauvin doing just that.

Jurors in Chauvin's trial now have seen that video and much more. Videos recorded by other bystanders. Footage from at least five police body cameras. Security video inside the store where Floyd allegedly passed a bogus $20 bill to buy cigarettes. Police dashcam videos. A video recorded by a witness through a car windshield.

And Tuesday, Judge Peter Cahill granted lead defense attorney Eric Nelson's request to admit into evidence an extended video from a city camera across the street from the spot where Floyd struggled with police. Allowing the jurors access to the video during deliberations would provide a clearer view of what happened than the portions prosecutors played in court, Nelson said.

But it’s not clear that the mountain of digital evidence will help the jury make a more informed decision about what happened. Our personal backgrounds, experiences and biases shape our interpretations of what we see, say psychology experts and others who have studied human cognition.

“There’s a question of whether it will ultimately lead us to get the truth or just create cacophony,” said Adam Benforado, a Drexel University School of Law professor and author of "Unfair," a book that says errors in the criminal justice system may result from biases and cognitive forces outside people's awareness.

"The premise that anybody will see the same footage and have the same opinion as everyone else is false," Benforado said.

Police chief sees incident in a new way

During the second week of Chauvin’s trial on murder and manslaughter charges, defense lawyer Eric Nelson showed jurors a new view of the incident that ended in Floyd's death.

On one side of the screen was the well-known cellphone video, recorded from the sidewalk. On the other was a recording from a police officer's body-worn camera as he and other officers restrained Floyd.

Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo watched the short clip and acknowledged that Chauvin’s knee appeared to press more on Floyd’s shoulder blade than his neck. He said it was the first time he’d seen that view.

What witnesses and jurors see – and how they interpret it – is a key element of court trials.

Chauvin is charged with second- and third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. Jurors must decide whether Floyd's death was caused by Chauvin, as the prosecution argues, or from Floyd's drug use and health problems, as the defense contends.

To do so, they’ll have to weigh more video and audio evidence – some of it conflicting – than likely has ever been presented in any major U.S. criminal case.

"There's never been a case that I've been involved in that had video over such a long time frame and from so many perspectives," said Dr. Lindsey Thomas, a former Hennepin County medical examiner, during testimony as a prosecution witness last week.

One bystander, many perspectives

Live videos, such as the one of Floyd's death that Darnella Frazier posted on Facebook, “texturize what you’re seeing in a way that testimony alone doesn’t do,” said Benjamin Burroughs, an associate professor of emerging media at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

While cautioning that he couldn’t predict the jurors' perceptions, he said, “We as an audience ‘believe’ livestream … because it produces this feeling of closeness to a major public event.”

Taken together, the videos presented by prosecutors in the Chauvin trial provide a nearly 360-degree view of the fateful struggle, giving jurors a you-are-there feeling, said Cynthia Cohen, a jury consultant from Los Angeles-based Verdict Success.

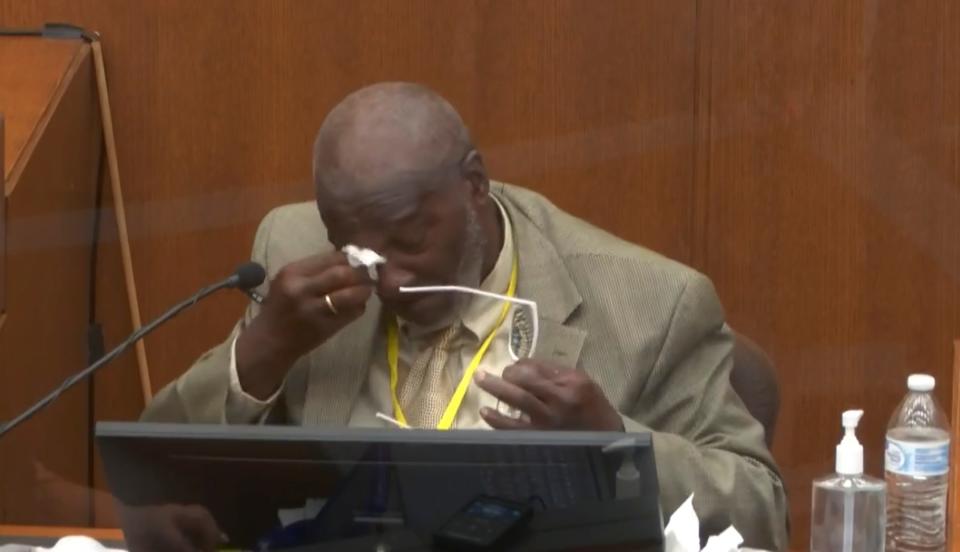

There was Charles McMillian, a 61-year-old Minneapolis man, seen on a courtroom video walking toward a security camera soon after officers started to struggle with Floyd. Then, a security camera with a different view showed him walking toward the scene and stepping off the sidewalk to get a closer look.

As the videos played, McMillian answered questions from the witness stand, describing what he saw and did. Jurors heard him in what appeared to be audio from Frazier's bystander video yelling to Floyd that he “can’t win” once the police get him in handcuffs.

After watching the videos and reliving the tragedy, McMillian broke down in sobs, prompting the judge to call a recess so the witness could compose himself.

Other bystanders who witnessed the struggle, including some who recorded portions, added their testimony on the witness stand.

“Different camera angles make the experience more profound,” Cohen said. “It’s not just the videos alone, it is the story that each bystander brought to the forefront and why each bystander turned on their camera.”

Emotional testimony: Darnella Frazier, the teenager who recorded George Floyd's death on video, says it changed her life

But too much video can overwhelm "anybody’s ability to process it all,” said Emily Balcetis, a New York University psychology professor who studies judgment, decision-making and vision science.

To make sense of the side-by-side videos that Nelson presented, Balcetis said, jurors' eyes had to scan rapidly, back and forth. Just 2% of human sight is high-acuity vision that takes in small details; the rest of what we see comes from peripheral vision, which lacks clarity, she said.

This means someone looking at the video clips would have difficulty processing and understanding it all, said Balcetis, author of "Clearer, Closer, Better: How Successful People See the World."

Videos are 'curated, constructed evidence'

The question for the legal system is how jurors interpret the narrative constructed by all the video and audio evidence.

“What has been presented is curated, constructed evidence,” Balcetis said. “It’s not objective" because the videos "leave segments out. ... Somebody has made a choice about what’s the best video evidence to include.”

That's true of many videos presented in trials trial. The difference in the Chauvin case is the volume.

Dr. Andrew Baker, the forensic pathologist who performed the official autopsy on Floyd's body, said he didn't watch Frazier's bystander video first. "I did not want to bias my exam by going in with any preconceived notions that might have led me down one pathway or another," Baker testified.

His comment referred to a well-known issue called confirmation bias, one that Balcetis suggested can affect decision-making in trials.

“We get a narrative in our mind about what we feel is happening,” she said. That narrative could arise from a preexisting belief, a theory developed based on other things we’ve seen, or from what someone tells us we’re seeing, she said.

“Then, we look for information that confirms that what we’re seeing corresponds with that narrative,” she said. “We don’t play devil’s advocate with ourselves by searching as ardently for things that would contradict that narrative.”

Balcetis suggested the judge could mitigate potential bias by instructing jurors before deliberations that they should pay equal attention to actions by Floyd, Chauvin and the other officers. But removing all bias "will be a big challenge," she said.

Video of high-speed chase persuades Supreme Court justices

A 2007 U.S. Supreme Court decision showcased the persuasive power of video evidence, Benforado said. The ruling focused on the case of Victor Harris, who was rendered a quadriplegic after he led sheriff's deputies in Georgia on a high-speed chase. The pursuit ended when Deputy Timothy Scott deliberately struck Harris’ vehicle with his patrol car, sending Harris’ vehicle off the road.

Harris sued in federal court, arguing that Scott violated his Fourth Amendment rights by unreasonably using excessive force. The trial court and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit ruled against Scott’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit.

When the case went before the Supreme Court, some of the justices said they had been prepared to uphold the lower court findings, which were based on a written summary of the facts and arguments. Then they watched a video of the chase, filmed from a law enforcement vehicle.

The court voted 8-1 that Scott’s use of force had been reasonable. A 2009 Harvard Law Review article titled "Whose Eyes Are Your Going to Believe" chronicled the turnaround.

Associate Justice Stephen Breyer told the attorney for Harris he had been prepared to affirm the lower court rulings. Then he saw the video showing how Harris drove as he fled officers. Breyer described seeing him swerving around vehicles and endangering others.

“Am I supposed to pretend I haven’t seen that?” he asked.

The majority decision written by Associate Justice Antonin Scalia said Harris’ “version of events is so utterly discredited by the record that no reasonable jury could have believed him.”

Some perceived video differently than Supreme Court

The law review article, written by Dan Kahan, David Hoffman and Donald Braman, put the high court's conclusion to the test by surveying 1,350 Americans about the chase video. A majority reached the same conclusion as the Supreme Court.

But Black Americans, low-income workers, residents of the Northeast and people who characterized themselves as liberals and Democrats did not, the article reported.

“Indeed, these individuals were much more likely to see the police, rather than Harris, as the source of the danger posed by the flight and to find the deliberate ramming of Harris’s vehicle unnecessary to avert risk to the public,” the article said.

Benforado said he worries that other perception and bias issues will emerge as more video evidence is introduced in court cases. He cited the possibility of juries seeing videos that have been sped up or slowed down.

"I wonder how we'll police that," Benforado said. “We may need new rules of evidence to deal with these problems.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Derek Chauvin murder trial: How will jury weigh multiple videos?