Mapping to monitor: how invasive species spread during Georgia floods

Coastal Georgia is carved by its winding waters: Tightly knit creeks, streams and rivers surrounded by the low-lying land in between. And nearly every resident of coastal Georgia has seen those waters rise after a hefty rain and sploshed their feet into the spongy, flooded ground.

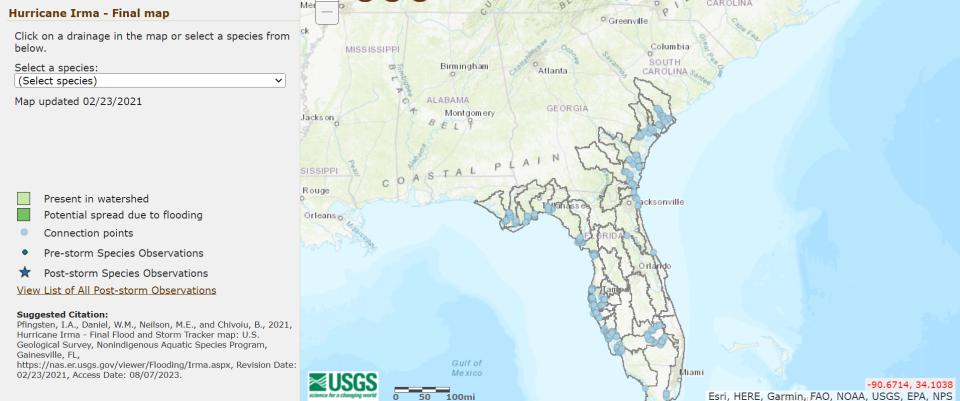

But what many may not realize is that when these floods take place, floodwaters aren't just reaching the ground ― they're reaching entirely separate bodies of water, too. Researchers at the United States Geological Survey and state agencies are mapping to monitor invasive species that use hurricane and storm-caused floods as portals to new ecosystems.

Terrestrial invasive species: Georgia DNR limits ownership and breeding of Burmese pythons, tegus and other reptiles

Angler's news: Bass anglers in Georgia might be surprised to learn where their catch originated

Mapping for the future

"(Invasive species) might move through a corridor that might not be typically hydrologically connected ... due to immense flooding that occurred in the region," said Ian Pfingsten, a botanist at the U.S. Geological Survey's Wetland and Aquatic Research Center in Gainesville, Florida.

Pfingsten focuses on specifying and identifying which animals and plants are non-native and have the potential to spread and alerting stakeholders, like local government offices and the Georgia Department of Natural Resources (DNR), about any discoveries or new introductions to the state or bodies of water. Using mapping tools, he and other employees at USGS are able to create maps that estimate how flooding may cause waterways to interact and target which waterways and species of concern stakeholders need to keep a vigilant eye on.

The Flood and Storm Tracker Maps, called "FAST" maps, are typically put out within a week or two of a flood or storm event as soon as USGS can get information compiled to develop and publish the maps for the public.

While these natural processes of storms and floods have always taken place, the frequency of flooding on Georgia's coast has increased as sea-level rise, tidal flooding, heavier storms and the paving over of flood plains have exacerbated the issue.

Research: Savannah's sea level is rising faster than other coastal cities. How is that possible?

Where the water is rising: Historic preservationists face new challenges as sea-level rise threatens Butler Island

Aquatic invasive species are any type of animal or plant not from the local region that have the ability to spread quickly and outcompete native species, gobbling up food, taking up space in habitats and causing the delicate balance of an ecosystem to run haywire. While most people think of fish or other animals, Pfingsten specializes in plants that can also cause big ecosystem disruptions, for example in Georgia the water hyacinth.

Pfingsten said his office maintains the Non-Indigenous Aquatic Species database, and this mapping project is a means of giving the people who conduct prevention and removal efforts the ability to apply USGS's knowledge of invasive species in a timely manner.

The agency mostly focuses on freshwater aquatic species, although it does deal with some marine plants and animals. Pfingsten said the maps are based on pre-existing information but also use reports from citizens and representatives from state agencies who are out doing fieldwork. He specified that the maps aren't doing data collection or active monitoring ― it's a tool meant to be a resource of compiled, aggregated data to present the possible introductions to the public and state agencies to take into consideration.

Monitoring the spread at home

Jim Page, senior fisheries biologist and aquatic nuisance species coordinator at DNR, said this information is improved upon and more useful when citizens participate. It's important for anglers, boaters and others recreating in Georgia's waters to get familiar with invasive species so they can report them and be sure to not spread them, accidentally or intentionally, from one body of water to another.

"A lot of folks don't think of the ocean as being a place where you're going to have problems, if you will, from animals that aren't supposed to be there," Page said. But the ocean, too, can get invasive species such as the lionfish that are all over Georgia's coast.

Lionfish are a venomous fish native to the Indo-Pacific and they are popular in the aquarium trade, which is how they arrived in the U.S. in the 1980s. They're an apex predator, and it doesn't take many of them to reproduce quickly and outcompete native species.

"They like to hang out on coral reefs and eat a lot of our native grouper and snapper and other species that are both ecologically important but also recreationally important and commercially important it to some degree to some of our anglers," Page said. In the ocean, Page said Georgia also has invasive tiger shrimp.

"There's a lot of outreach and education effort because prevention frequently is our best tool for controlling or managing invasive species," Page said.

In freshwater, Page said South Georgia struggles with flathead catfish, a large, apex predator that can grow to more than 100 pounds. They are ravenous consumers of native catfish and red breast fish that are popular for anglers. Removing flatheads is a huge task, and the Satilla River is one place the DNR has been working on the flathead catfish problem.

"They were established in the Ocmulgee River first in the early-mid-'70s, and then we're pretty confident that anglers then moved on from the Altamaha to the Satilla in the mid-'90s," Page said. There's some detective work to the spread: he said that their reason for this scenario is that some of the first specimens found in the Satilla had been tagged in the Altamaha, which typically don't connect. While humans contributed to this spread, floods can also give the fish opportunity to spread even further from their new stomping grounds.

Education is key, Page said. The vast majority of anglers and recreation participants are respectful, abide by rules and value natural resources. Giving more information about invasive species helps regular users of the waterways identify invasive species, prevent spread and can make it so the DNR has more people alerting them of where those invasive species are to improve management efforts.

And constant vigilance is necessary: new invasive species can be located at anytime. For example, Page said that as recently as 2019 Georgia had a new incidence of a fish called the northern snakehead. He said that the snakehead is also an apex predator and is sometimes called the "Frankenfish," because it can breathe air and slither short distances on land like a snake.

To learn more about the Georgia DNR's aquatic nuisance species, visit georgiawildlife.com/ans.

Marisa Mecke is an environmental journalist covering climate and the coast. She can be reached at mmecke@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: USGS maps invasive species in floodwaters