Mariel Hemingway Reckons With Mental Health, Woody Allen, and ‘Manhattan’: ‘I Was a Kid’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“We’re in a mess right now,” Mariel Hemingway laments. “I think of my grandfather and think, what would he see in this? How would he look at this, and what would his perception of what’s going on be? This is not an America that we recognize.”

Hemingway’s grandfather, of course, is none other than Ernest Hemingway, the macho, laconic, and boozy literary titan, and the “mess” is thanks in no small part to President Donald Trump, the cowardly, teetotal business fraud and game-show host who’s allowed the novel coronavirus to run roughshod over the country, claiming over 215,000 American lives and leaving tens of millions out of work.

The actress has been spending lockdown at her family home in Sun Valley, Idaho—the place where she grew up and where, on the morning of July 2, 1961, her grandfather took his own life. Mental illness, suicide, and alcoholism run in Hemingway’s family, which she explored in the 2013 documentary Running From Crazy. She’s since dedicated her life to helping those battling mental illness, giving speeches across the country, launching the Dead Poets Foundation (a suicide-prevention nonprofit), writing books, and producing documentaries.

Hemingway’s seen it all, having braved her chaotic family and entered Hollywood at the age of 14, with her Golden Globe-nominated turn opposite sister Margaux in Lipstick, and then star-making one as 43-year-old Woody Allen’s 17-year-old muse in Manhattan. (She wrote about her experiences in the 2015 memoir Out Came the Sun.) The role has been thrown into sharper relief given the subsequent abuse allegations against Allen—by Babi Christina Engelhardt, the 16-year-old model who inspired Manhattan, and Allen’s adopted daughter Dylan Farrow, who claims he molested her when she was 7. Her latest film is The Wall of Mexico, a satire about a wealthy Mexican family who build a wall around their property to keep poor, conspiracy-minded Americans from stealing their well water.

George Takei: ‘Evil’ Donald Trump Jr. Tried to Cancel Me

Though she’s understandably down about the current state of things, there is a big bright spot: her longtime partner Bobby Williams.

“I’m going to be 59 soon, and to think that this is where we are? Although maybe the world has to break before a new paradigm comes. It’s through chaos that we discover the truth about things,” she offers, later adding, “I’ve found my person, and I’ve found my place. As much as there have been hardships and scariness, it’s like I’m 18 again.”

The Daily Beast spoke with Hemingway about her journey through Hollywood—and life.

I have a unique name too so I’m always fascinated by their origin. Is it true that you were named after the Cuban port of Mariel?

Yes! I was indeed. Obviously my grandfather spent a great deal of time in Havana, and my parents lived there for a couple of years before I was born. My dad used to go to this little fishing village called Mariel—prior to the Marielitos coming over from Cuba, which means I was never so enthusiastic about sharing where my name came from. They used to go there and fish, and my dad loved the place, so that’s what I was named after. I’ve been there quite a few times, probably seven times, and I love the Cuban people. I think it’s an amazing country.

Your grandfather is quite the icon over there.

I know! And they just like me for being me. I’m like, wow, this is great, I don’t have to do anything! [Laughs] You just have to be related to Ernest Hemingway and you’re good to go.

You know, I think the most expensive cocktail I’ve ever purchased was at Bar Hemingway in Paris. I wasn’t really paying attention to pricing, got the bill, and my eyes practically bulged out of my head.

I also went there! One of the first times I went to Paris was with my father, who took me when I was around 11, and we stayed at the Ritz in Paris, which was pretty amazing. I remember going into that bar and… it was expensive, and it’s probably even more expensive now!

Wall of Mexico is certainly a timely film. It provides a commentary on American xenophobia toward Mexicans via a role-reversal, where the Mexican family is rich and isolationist and taking advantage of white laborers.

Film is an art form where you can express an opinion without blatantly expressing an opinion, and is a reflection of our time. I like that it comes at it from this inverse way that’s unexpected, surprising, and ironic. And for me, doing independent film and supporting independent film is important—especially in the world that we live in—because it’s one of the last major ways we can express ourselves culturally, our cultural systems and insecurities, and also what brings cultural change. In these tumultuous times, I like to think that good things are coming. At least I want to hope that. There’s got to be something good at the end of all this.

Hopefully November 3rd.

Yeah, I hope so!

And it is a meditation on Trump’s wall on the U.S.-Mexico border. The xenophobia and anti-immigrant mindset of this administration has been pretty shocking, and seems to run contra to what America should aspire to be.

I’m political in my own way but I refuse to share that because I think it’s a slippery slope, but yes, I’m a big believer in how America is made up of people from all walks of life—and this is not a commentary on who I like or don’t like—but America’s always embraced the fact that we’re mutts, and that’s what makes us American, and I have to believe that we can get back to an America where we embrace other cultures and people, because we are not made up of one kind of person. The system has been breaking for a long time, and I think that things need to change.

When we talk about representation in cinema, I’ve long admired the light you’ve shined on the LGBTQ+ community—with roles in Personal Best, Roseanne, etc. What inspired you to give voice to the hopes and struggles of that community well before even films like Philadelphia came out?

Well, I’ve always felt that people have all kinds of relationships, and these relationships are about connections and love. Even when I was a kid and I played these roles, I never thought it was wrong. I never saw the connection of love from that perspective. I just thought, that’s who this person resonates with. It never bothered me, because I never saw it as wrong or had any judgment about it. Because really, who am I to say?

I grew up reading your grandfather’s books and I’m sure you get asked this ad nauseam but what do you think of his work?

I loved my grandfather’s work. I loved it even as a child. When my father took me to Paris when I was 11, he had me read A Moveable Feast and took me to all the places he grew up. I’m producing a short-form television series about A Moveable Feast, and it’s because of my love for my grandfather’s vision of the world—how he saw nature, how he saw women, how he saw relationships. He’s been written about as this macho male chauvinist, but that was a persona. When you really read his writing, he was so understanding of relationships, men and women, how you live life, and the fears that arise when facing danger. I’m so blessed to be a part of that heritage, and I wish I had that kind of ability to translate words into images in somebody’s mind.

You mentioned the “macho” persona, and I’m curious how you feel about that sort of caricaturish representation of him in things like, say, Midnight in Paris?

Actually, I loved it. I thought it was hilarious. I think humor is the best way to express people’s opinion or vision of somebody. The fact that he comes on the screen and drinks for probably two minutes—he’s gulping and gulping and it’s like it never ends!—and in that moment of comedy, you know he drank too much, lived too much, and was too much. When you honor somebody that way through humor, it’s one of the great ways to honor somebody.

It seems his drinking does get glamorized a lot, but at the same time it doesn’t seem like enough people know about the root cause of that drinking.

Thank you for that. Kind of my mission in life is to help people with mental-health issues that use alcohol to self-medicate, and realizing that my grandfather was this incredible man who lived this great life, and was he drinking because he was a “man’s man” and wanted to beat people up, or was he drinking because he was going through a tremendous amount of pain that was very difficult to negotiate every day of his life? I understand addiction and going through life that way as a means to survive.

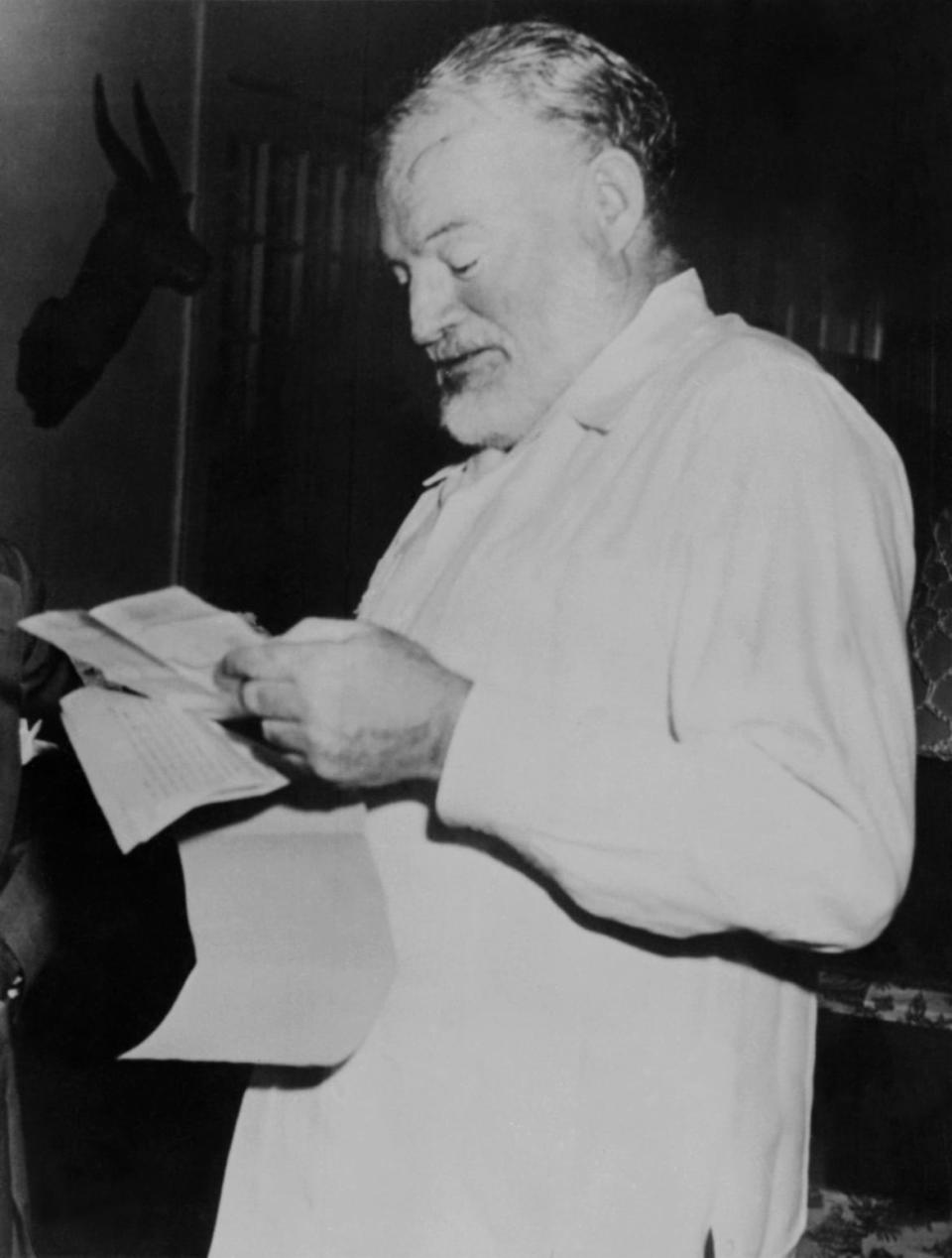

A photo taken in 1952 shows writer Ernest Hemingway reading a letter to learn that he won the Pulitzer Prize for his novel The Old Man and the Sea.

I read your memoir and have heard speeches you’ve given about growing up in the Hemingway household as a kid, cleaning up liquor bottles and scrubbing blood from the walls. How did you manage to fight off the demons, so to speak?

I don’t say that to be like, “Oh, poor me.” I grew up in Sun Valley, Idaho. I did clean up liquor bottles and blood, and was afraid at times for my life. When I started to understand that that was not normal, I was like, “Oh shit. I don’t want to end up like that.” My ways of survival were like going full-tilt into “health”—and I use quotes because I thought what I was doing was healthy, but it was obsessive. It was an addiction—diets, following “holistic” doctors and gurus. I was constantly searching because I was afraid that I would wake up one day and be crazy just like my family. But once I delved into the reasons why my family was the way that they were, there was no fear. When you understand your history, and understand where you come from, you get to make your own choices.

You entered Hollywood at 14, which is an incredibly young age. I can’t imagine entering the spotlight at 14. And there are many horror stories from people who entered the industry so young. What was that experience like for you?

At times, it was a challenge. But I kind of fell into it. My sister asked me to play her little sister in this movie called Lipstick, then I got good reviews and got to go out to L.A. and make movies. Really, I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing. Somehow I did one TV thing, and then Woody Allen calls my house in Idaho. I don’t know who Woody Allen is, and my mother was all nervous and like, “Yeah, you do! He was the one rubbing that egg in that weird movie,” and I was like, “Oh…” She’s like, “Get on the phone! He’s on the phone for you.” I was completely oblivious to the process but lucky that I got to do incredible projects very early in my life. At the same time, after 22, there was a rude awakening that life was far more complicated.

I have always been very afraid to not be normal. I never wanted to seem “abnormal,” or be seen as the kid who lost track of who they were or where they came from. I was always an Idaho girl, and that was really important to me. It probably stilted my ability to become a huge actress but it was important for me to get married, have kids, and be a mom. And I really wanted to do that well, because I grew up in a house where people drank too much. I was doing all these things that you do to correct the past. So I kept Hollywood at a distance. Still to this day, I’m like, Shit… I have to go to a premiere?

Was part of the reason why you kept Hollywood at a distance too because you seemed to be targeted by a lot of creepy men? In your memoir, you wrote about Bob Fosse chasing you around a hotel suite and that Robert De Niro also made a pass at you.

I feel kind of bad about the De Niro story, because it’s been taken out of context. He was an actor’s actor, and when I met him first he was playing Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull, and he was a method actor. I didn’t really understand anything. And I met him years later at an audition for Awakenings, and he couldn’t have been kinder or sweeter. I think I left that story out, and I shouldn’t have. But I just didn’t understand method actors, and that whole thing. With Fosse, did he do some strange things? Yes, he did. But I also said no, and he respected that. He was kind of periodically angry with me, but he respected me at the end of the day, and I learned a lot from him. Hollywood is strange. In this world that we live in now with everyone talking about what happened to them, I could name a lot of experiences in my life. But I was just too much of a prude, and I had an inherent thing of, “No, I’m not going there.” I think I was respected in that regard, and luckily so, because so many have had not-so-good experiences.

I grew up enjoying Manhattan but I rewatched Manhattan about a year ago for the first time since I was a kid, and knowing what we all know now about Woody Allen, I certainly viewed it with a different lens. What is your relationship with that film like now?

That film put me on the map. I mean, it made me an actress and made me want to act. I had an amazing time making that film. Woody Allen was wonderful to me. Did he like me? Yeah, he liked me. I didn’t have a relationship with him though. He respected that I didn’t want to have that. I was too young. I was really young. I was way younger than the girl I was playing in the movie. And for me, I look at it as this jewel of a film—and I will always think that. I don’t know [Allen] anymore, and my experience with him is not of this dark, ugly thing. Yes, I was a young woman. And yes, would Woody have liked to have… with me? Yes. But I was too young…

There is an episode you wrote about in your book where Woody Allen came to stay at your home in Idaho. You were just 17 and he was 43, and he propositioned you and repeatedly begged you to let him take you to Paris.

Yeah. Ugh. I was like, “I’m not going to go to Paris with you, because I don’t think I’m going to get my own room.”

You saw through that whole ruse.

I guess it was a ruse. People can view it in many different ways but I was respected when I said, “No, I can’t do this because it’s not right,” and then he left. What was sad to me at the time was that, because I felt he thought I was intelligent and all this other stuff, it felt like I was losing a family member, or a friend. But you know… you move on with your life.

Mariel Hemingway and her partner Bobby Williams

Watching Manhattan again though recently, and knowing everything we know now about Woody Allen and his taste for incredibly young women, the age gap—a 42-year-old man with a 17-year-old girl—really struck me as strange and far from appropriate. And you were 16 when you filmed it, right?

Yeah, you’re right. It is crazy. And as a parent, if I watch it from that perspective—a woman my age—I’m not going to lie to you, I will judge that shit all over the place, and be crazy with that. If even somebody who was 60 was after my daughter at 30 I would be wildly uncomfortable. But especially 16? I was a kid.

But when I said, “That can’t happen,” and that was respected, that’s just how it went down [with Allen]. But… I certainly judge that stuff. I don’t like if older men are going after 16-year-olds, because for the most part, 16-year-olds really are kids. Even though I thought I was super intelligent and worldly, I’d never had a boyfriend before—or slept with anybody. So… I didn’t know what I was getting myself into.

If you could do it all over, would you enter Hollywood at 14 or perhaps wait longer?

Would I have done it differently? I don’t think so. It helped me to leave my home, which was emotionally challenging for me and exhausting—because my mother was sick, and all that stuff was going on. It gave me a lot of opportunity, and I don’t know if I’d have become an actress if I’d done it by the numbers, like most people. I probably lost out on some childhood experiences, but more so from caring for a mother who had cancer and a family who had been in their state of pain. It was more from that, that made me lose out on childhood. Hollywood didn’t make me lose out on childhood as much as me thinking I would be the person who would fix my family. It’s one of the reasons why I do a lot of talks on mental health, because I think there are a lot of people who have had similar experiences.

And you’re working on a documentary about teen-suicide prevention?

Actually it’s not a documentary but a series that I’ll be presenting and hosting on the prevention of suicide for teenagers. But I also think it will be for a lot of people. I’m sure you’re aware that there are so many more suicides now with COVID, the financial issues people are having, our government. People are freaking the fuck out, and they need help, and they need to know that they’re not alone. My mission is to tell a story but also give solutions. I want people to know that there is a community out there that can support them.

You know, people stole from me. The world is just bizarre. Shit falls apart, and what you thought would never happen, happens. There are so many people in the same position. The world is bizarre and scary but I’m such a fighter that I always think we’ll find a solution. I’m never going to back down. And I’m convinced that my own personal struggles were there so that I can see the perspective that other people have that get in such dire positions that it freezes you and you don’t know how to move forward.

If you don’t mind me asking, who stole from you?

It was somebody who worked very close to me. They were stealing money. An assistant—it was an assistant and a bookkeeper. It’s just dumb. It’s the same old Hollywood story. But you know who’s culpable? I am. I didn’t open my eyes to it. I trust people, and that’s a lesson on me. Bad on me, and I feel like an idiot, but I only have myself to blame, because I wasn’t paying close enough attention. So, how do I move forward? Because I am a trusting person, and I don’t want to lose that.

I think you’re being pretty hard on yourself! I don’t think you can blame yourself for dipping a toe in the water and getting bitten by a leech.

You’re right. I appreciate that you said that, and now I don’t feel as bad. But moving forward, I just need to have my eyes open.

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.