From the Marines to TV to government, retiring County Judge Downing Bolls has seen it all

County Judge Downing Bolls Jr. said he has simple plans for his retirement after his successor, assistant district attorney Phil Crowley, takes over after the first of the year.

“(I’m) going to kind of relax for a while and get some sleep,” said Bolls, 72. “After that, it’s whatever the boss has in mind for me.”

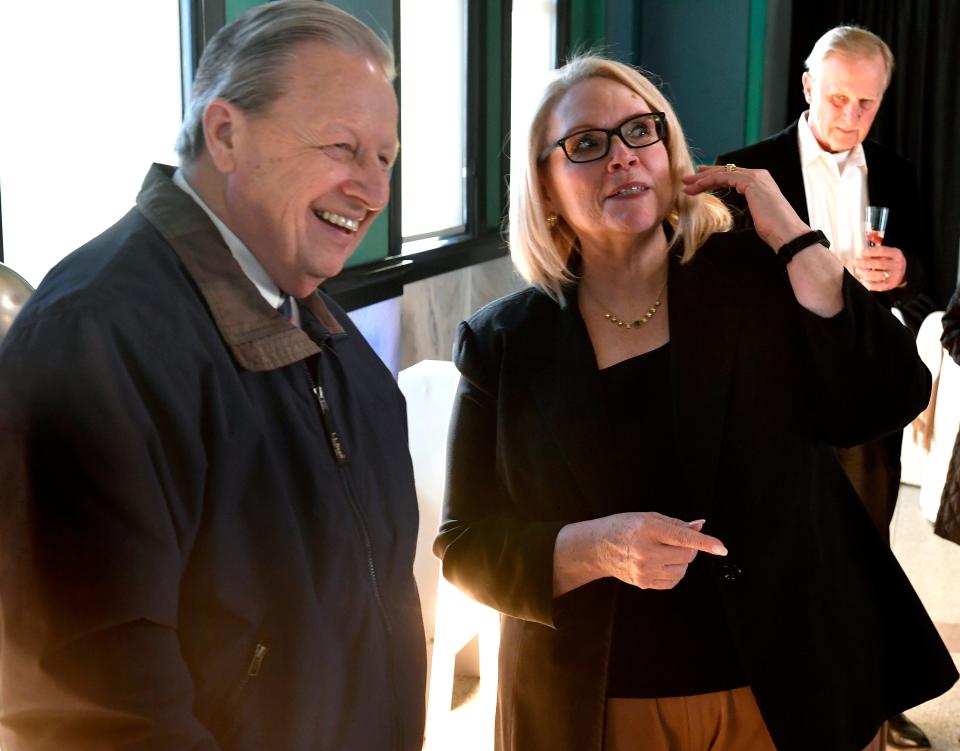

“The Boss” is Bolls’ wife, Debbie, who started as his competition in the world of Abilene radio.

The two competitors went on to marry in 1978 − and now have two adult children and two granddaughters, ages 6 and 9.

An unlikely contender

Bolls was skeptical when the idea was floated to him to run for office in 2010, after his own 33-year career in local radio and television news following military service in the U.S. Marine Corps and earning an online master's degree in conflict resolution from Abilene Christian University in 2008.

"I got a phone call one day from somebody who (asked if I’d) ever thought about running,” he recalled. “I kind of laughed it off. I had never run for City council. I had never been any kind of public figure like that. I just didn't see it."

Bolls was concerned he wasn’t an attorney, but he soon learned the county judge position is the only judicial position in Texas that doesn’t have that requirement.

He ran the idea by Debbie, who told him it was something worth pursuing.

“She worked with me, she helped out in the campaign,” he said. "It was a joint effort for both of us, and the campaigning part was fascinating. I loved it, though. I enjoyed talking about issues."

Outcome 'in God's hands'

Bolls remembers getting a call from a woman who told him that while she’d normally never vote for a Republican, she had voted for him.

Afterward, she stopped by her church and lit a candle for him, he said.

At that point, Bolls decided the outcome was literally “in God’s hands.”

He ran against attorney Curtis Tomme after the previous county judge, George Newman, retired.

“I think my opponent ran a good, clean campaign,” he said, with no mudslinging.

Bolls learned a valuable lesson from the experience, something he'd seen in action before but perhaps needed a reminder about.

“If you don't take the chance and don't go out there and try … you never accomplish what you set out to do,” he said.

Starting out

Bolls was born April 30, 1950, the hospital at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Miss.

The middle child of five, he describes himself as the kind of kid who had to tag along with everyone else.

And he tagged along with his family to various places throughout the world as part of his father's military career.

“You move around as the military needs you to move around,” he said, noting that later his folks “always apologized to us for not being in one place.”

While it was a somewhat "nomadic" existence, it sparked in him his own interest in a military career he said, which consumed his thoughts as a young person.

“I always wanted to be in the infantry,” he said. “In Alabama, when we were living there, you’d see the National Guard out training all the time. I just thought that was a perpetual camp-out.”

His family's extensive travels "allowed me to go places and see things in the world that I don't think sometimes many Americans get a chance to see,” he said.

When one is living in Germany just after the end of World War II, for example, “it's a whole different environment that you're in,” Bolls said.

“There was a lot of residual still left over after that war – supplies and things like that were being reused,” he said.

Bolls found through those engagements with real life a love of history early on, even though he didn’t do well in the subject at school.

But it would follow, and later help define his life.

“I was always kind of the dreamer,” he said. “I wanted to get out and see things and go places and do things.”

Abilene ties

His mother was a schoolgirl from Abilene, Texas, who met her future husband during World War II at Camp Barkeley.

He was a training sergeant and she worked as a clerk at a local five-and-dime.

When his father was transferred to Arkansas to serve at Fort Chaffee, Boll’s mother was a high school senior.

He sent for her, as was common at the time, Bolls said, and they got married. She earned a GED years later.

With those local connections, Abilene, was always a second home for Bolls, who came here to visit his grandparents.

“I got a chance to see this town grow a little bit year after year after year,” he said.

Among other adventures, Bolls remembers himself, his cousin and a friend they’d made here playing around with a recovered – and, as it turned, out live – artillery shell their friend found.

The youthful enthusiasm Bolls and others felt was dampened when it was recognized it for what it was.

“We decided to go down and show this shell off to the men that were in the family, they were all down there for (a) family reunion,” Bolls said. “… They called the police."

Bolls' memory is of a group of men sitting in lawn chairs, surrounding the shell so that no one would get near it.

“When you look at what the blast radius was on a howitzer shell, it would have killed all of them if it had gone off,” he said.

The mandate

One of his first jobs, foreshadowing his career in media, was delivering The Washington Post.

After doing his morning route, there would always be a few papers left over.

“As I was coming home each morning, I would always take that leftover edition of the paper and start to look through it,” he said.

That was around the time of the 20th anniversary of D-Day.

“That was a great time to learn for me because President (John F.) Kennedy had just been elected,” Bolls said. “I remember when he got up and made his remarks in his inaugural speech.”

Living in Washington, D.C., Bolls remembers it was a cold day, with snow melting on the ground.

While most remember Kennedy’s famous “ask not” maxim, Bolls said he recalled something different, the president saying the torch had been passed to a new generation of Americans.

Bolls instinctively knew the president was talking about his generation, and the words had a profound effect on him moving forward.

Finding purpose

Bolls graduated from Burkburnett High School in 1968, with a future both certain and not.

“Graduation was coming up and my grades were not good enough to get me into college,” Bolls said. “I knew and understood that I came from a family with five kids in it and my parents were trying the best they could to get kids through college.”

Bolls, 18, knew the GI Bill was likely his ticket to further education.

His family moved to Abilene when his father was stationed at Dyess Air Force Base.

His father, an officer, told him he could go into the Navy or the Air Force, but by no means could he go into the Army or the Marine Corps.

“His sole reason was because he didn’t want to me go to Vietnam,” Bolls said. “… He objected to his children fighting in a war he didn’t feel it was theirs to fight.”

Bolls didn’t want to go into the Air Force because he was worried about someday serving at the same base as his father, likely in a much more menial role, and he “didn’t have the smarts” to become a combat medic in the Navy, he said.

Despite his father’s prohibitions, he really wanted to go into the Marines.

“The whole time, I said, ‘He’s going to be mad at me when I do it,” Bolls recalled. “But I was 18 years old, and I could make that decision for myself. So, that's what I did.”

He told his father at the dinner table during a customary ritual. When it became Bolls’ turn to say what he'd done that day, he told his dad he had enlisted.

His father asked which branch he’d picked – the Air Force or the Navy.

When he heard Bolls’ answer, things got “real quiet,” he remembered.

His father got up from the table, walked into the front bedroom and “just kind of closed the door and turned the lights out.”

Bolls knew his dad was disappointed.

“As a parent now, I can tell you that I completely understand where he was coming from what he was thinking about,” Bolls said.

But Bolls again recalled Kennedy’s words, and his response was simple.

“This may have been your war, but it's now my war,” he remembered saying.

He was never sorry for the decision, he said.

“The Marine Corps was great for me,” he said. “It gave me the discipline I needed. It showed me, if nothing else, that you can really do anything you set your mind to do if you're willing to work hard enough for that.”

Going to Vietnam

When he entered the Marines, Bolls was sure he’d see combat.

The military was something that he’d considered joining even as a child, with about 500 toy soldiers in his toybox and enough pieces to equip a “well-established” battalion in his room.

But combat wasn’t in his future. When he got in, he tried to get to Vietnam as quickly as possible but could not go.

That’s when he went to volunteer for radio school in the hope he could get into a unit as a radio operator.

He was working as a communications center operator when a message came in that they were looking for people to send to embassy school.

“A couple of nights later, a message comes in (that) says I’m supposed to report to Marine Security Guard School in Virginia,” he said.

Not long after, Bolls got the message he would be going to Vietnam.

“That's how I wound up going to Saigon, stationed at the embassy,” he said.

He got there in 1970, following on the Tet Offensive. It ended up being fascinating, he said, because there were a lot of "big players" in the war that sometimes came through.

Shielded by rocket protection walls, one could turn on the radio at night and listen to units out in the field, including firefights, which Bolls described as a “surreal” experience to hear.

One of the posts he stood, and another early brush with journalism, was at the Joint U.S. Public Affairs Office in Saigon.

“I was working security for all of the journalists who were coming in and out covering the war,” he said. “They’d go out in the field and stuff like that, and then come back and file their reports. So, that was very interesting work.”

Bolls provided security at U.S. embassies in Saigon and Guatemala City. He was discharged in 1972.

Despite his father’s worries, the Marine Corps ended up giving him what he felt he needed.

“It really did give me a lot of discipline, a lot of things you need to do well in life,” he said. “I learned so much, and some of those lessons were painful lessons. But you remember. You carry them with you.”

A real education

Bolls got out of the Marines, came home and, as he’d promised his parents, went to college.

His father, who had attended there himself, advocated him going to then-McMurry College and encouraged him to get a business degree.

But after attending McMurry for about a year, he decided to follow an early passion driven by a love of radio and television to its end.

He went to Southwest Texas State University (now Texas State, in San Marcos) to pursue journalism, with a specialty in advertising and public relations – a field where he thought there was plenty of money to be made.

“But all this time I was doing it, I kept getting this call to go into news,” he said.

Because of his duty with the U.S. Department of State in the Marines, he had a second major, political science/international relations, which proved helpful in time.

Finding a career

His last year in college, Bolls needed a job.

He saw a newspaper ad looking for a disc jockey at one of the local radio stations.

Bolls said he’d fallen in love with radio at a fairly early age, and remembers sneaking into his sister’s room to snag her radio for his own late-night listening, picking up “skip” stations on the AM band.

“You could listen to Chicago (stations), you could listen to stations in Mexico, these big super stations,” he said. “When I joined the service, I think what I really wanted to do was try to become a broadcaster of some kind, but that wasn't going to work.”

But when he stood guard duty at rifle ranges, often big as four or five football fields and all “basically underground,” he found the acoustics pleasing and practiced his delivery and voice inflections.

It took two times for him to pass his third-class license test, he recalled.

Books on radio broadcasting made it clear newcomers would likely start out at the very bottom, but Bolls said he was willing to do anything to get into the field.

He got hired, doing Sunday morning sign-ons, the “worst air shift there is.”

“You don’t really do any announcing,” Bolls said.

But it allowed him to work alone, learn his craft, and catapulted him into his eventual career.

Coming home

After graduating from college, Bolls returned to Abilene and went to work for KFMN radio before becoming a news reporter for KRBC in October 1976.

He would go on to become the station's news director and vice president for AM programming.

While working at KRBC's radio station, he met his future wife, Debbie Elliott, her on-air name after she went to work for KFMN.

She, too, came from a military family, and the two would see each other out and about when covering stories.

"He said there was something about my shiny blouse that made him look at me," she recalled of the first time they waved at each other at an Abilene Chamber of Commerce news conference in 1977.

After a while, he asked her out. They had their first date around Thanksgiving, but she stood him up for a New Year's Eve outing.

But she warmed to him and made the next move.

While coming out of a news conference one day at then-Abilene Civic Center), she asked when was he was going to ask her out again.

That was pretty bold, she admits now, considering she'd stood him up.

"But we were pretty much a thing from that point going forward," she said.

Making it work

Downing Bolls remarked at the time it “seemed like blasphemy” for the radio station managers to have two employees from competing stations dating, let alone deciding later to get married.

“They were going, 'You’re marrying your competition in this market – are you out of your mind?’” he recalled.

It affected both of their jobs.

“There was a period of time where they didn't trust you,” he said. “My station, they would not let you in on promotional ideas and stuff like that because they thought you're going to go home and tell your wife and she's going to know what we're planning. She must have been getting the same thing over at her station.”

But Debbie Bolls said she doesn't regret getting to know the man across the room.

"What really attracted me was just his sense of humor," she said. "He has a really wry sense of humor. He has just a wealth of knowledge. To him, everything is a challenge to figure out or (take a) deep dive on."

She liked him so much she suggested the first time he met her parents he ask for permission to get married.

"I said, 'Oh, they're gonna love you. You're so much nicer than what they've seen me with,'" she quipped. "I think it was just meant to be."

Dream team

Going forward, the Bollses knew they were a team, not each other’s competition.

“We knew that the competition in this market was the television stations and the television news operators,” Downing Bolls recalled. “Everybody would call the TV stations and they'd never call you at the radio station.”

News conferences, for example, wouldn’t start until TV stations got there.

“That used to drive me crazy because I had other things to do and other places to be and things to follow up on,” he said.

The way to win, Bolls said, was to get news out before the TV stations could.

"When one of us would have a story the other one didn't have, we could listen to each other on the radio and hear their story," he said. "We had worked out an arrangement where once you run with it on the air, it's free game for whoever wants to do it. So, we were constantly following up.”

Radio ratings came up, and “we would run those stories so many times (that) by the time 6 p.m. rolled around, it was old news,” Bolls said.

Eventually, Bolls said he got some “blowback” from station management about the need to do more lifestyle stories.

“That didn't sit well when your life is covering hard news,” he said. “So, we could, we could start to see their handwriting on the wall, that radio was getting ready to change.”

It wasn’t long before management changed at Bolls’ station.

“The new guys came in to say they were cutting the amount of news we were doing way, way back,” he said. “And so it was at that point that the opportunity came to transfer over to KRBC television.”

The sun always shines on TV

Bolls took a job as an assignment manager at the television station.

Transferring to the world of TV was “a little bit different” because it was more labor-intensive, Bolls said, and – of course – visual.

He spent 10 years in radio and the rest of his 33-year media career in television. He left TV as the station's evening news anchor when his contract wasn’t renewed.

Being in the anchor’s chair gives one some recognition, but not always accurate recognition, Bolls recalled.

Plenty of times people would confuse him for Bob Bartlett, a name for decades now at KTAB, or even Wayne McCormick, the former longtime anchor for KTXS.

Eventually, just being “The News Guy” was often good enough, he said, and Bolls recalls sharing a few chuckles when he’d run into his on-air competition and colleagues.

“We thought it was funny because you spend so much time trying to get your name and your face out there for people to know," he said.

Debbie Bolls recalls it was "challenging," especially raising children, for him to be gone essentially from 7:30 a.m. to around 11 p.m. some days.

"But it was a job and with everything he's ever done, he's just tried to do his very best," she said.

Slings and arrows

Bolls and his colleagues endured other extremes, such as being effectively knocked off the air for 10 months because of the switchover from analog signals to digital and a fight with the local cable company.

When Bolls’ contact didn’t get renewed in 2009, he'd expected it was coming, having been through ups and downs in the TV industry.

But he didn’t want to burn any bridges, paint himself as a victim, or create any problems − lessons he credited his father with teaching him.

“I got where I am because of the freedom that I had, and the people who first hired me and entrusted me with a great responsibility,” he said − though he did hire an attorney to help him through the process.

A new direction

Bolls was under a no-compete clause, which meant he had to find something else to do.

He was unemployed for a while, and got training through the Texas Workforce Commission to help him expand his skill sets and find another job.

He met many people whose circumstances were extremely similar.

“They had been a career employee for some business, they had worked there for 20 or 30 years, and they'd been let go,” he said.

Bolls said his decision to seek the county judge position after that fateful phone call is an extension of how he’s chosen to live his life.

"I tell people that everything I've done in my life, I have tried to learn from it and take it to the next level," he said.

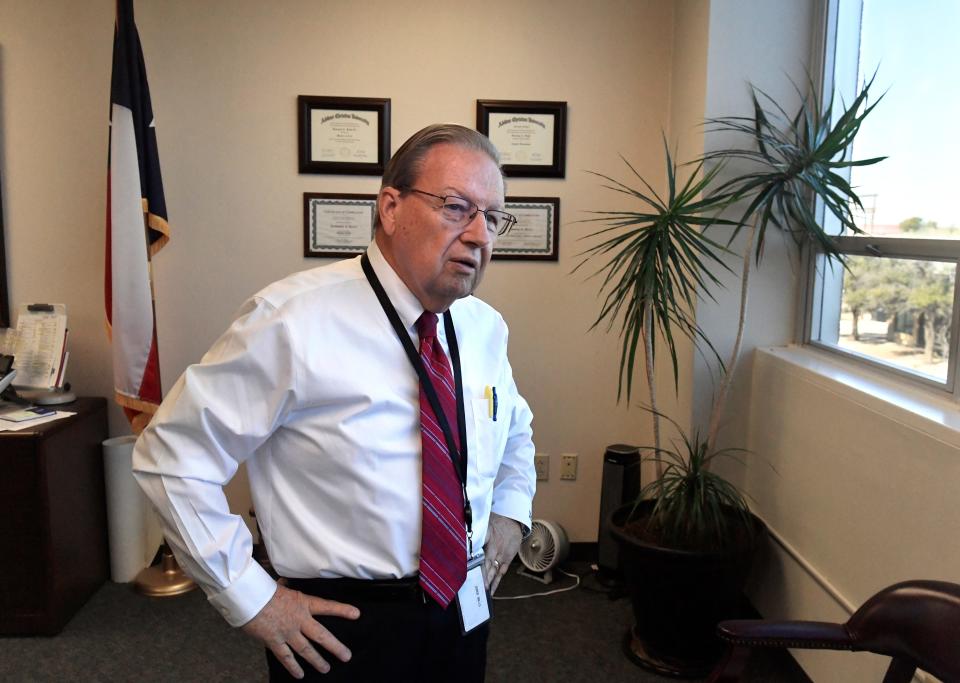

A whole new world

Bolls said the county judge job has opened his eyes to “so many things that you had no idea even existed in this community.”

That includes the level of mental illness present here.

“We're a catchment area, a regional area for mental health services,” he said, meaning Bolls hears a significant number of those cases.

Add to that, “you never know what’s going to walk in the door,” he said.

“It's part of what makes the job so fascinating,” Bolls said.

Debbie Bolls said she believes her husband brings a compassionate touch.

"He does most of the uncontested probate, so he's dealing with a lot of shattered spouses and children that have lost their parents," she said. "He just knows how to work with people in some of their most vulnerable situations."

Part of a team

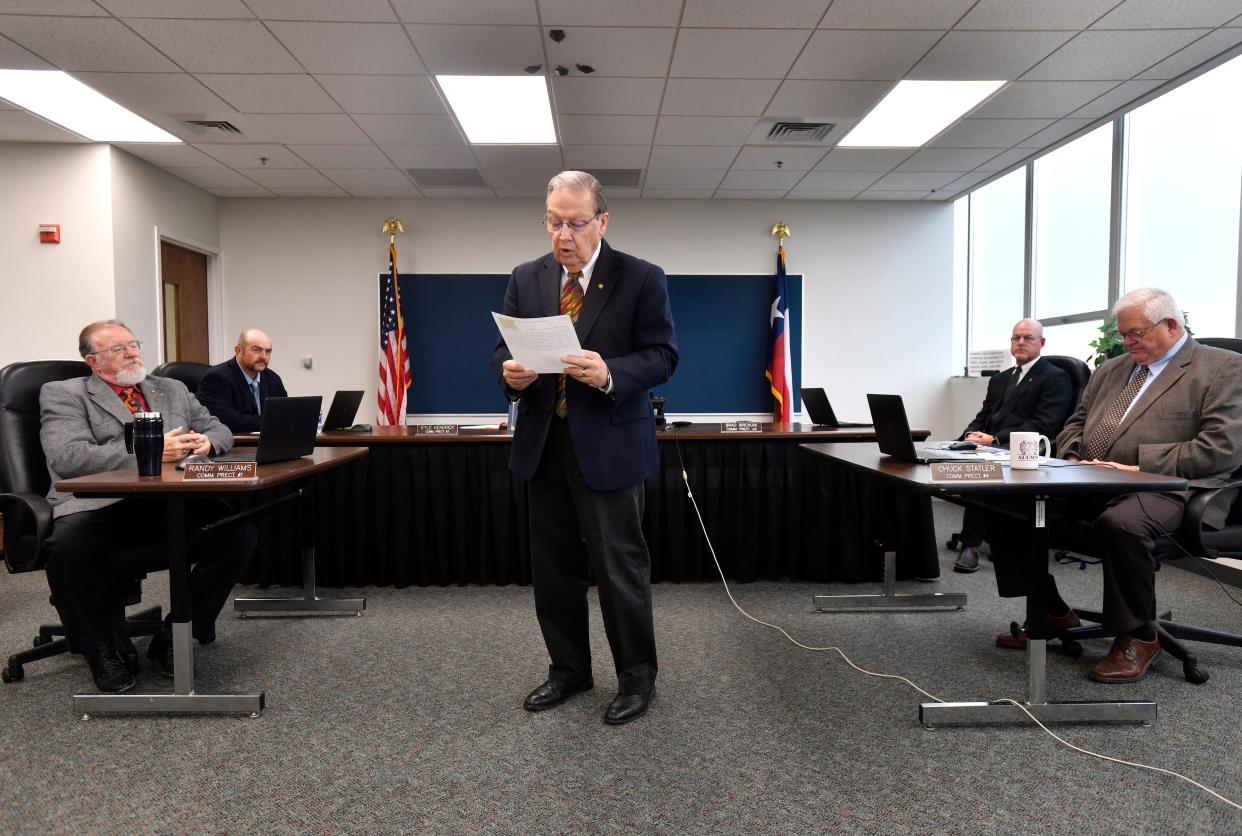

Bolls is complimentary of the four county commissioners he works with, saying that one of the benefits of working with each is how different they are from one another.

“They each bring something special to the table,” he said, whether it’s the law enforcement background of commissioner Precinct 3's Brad Birchum, the juvenile justice background of Precinct 1's Randy Williams, the studied, quiet consideration of Precinct 2's Kyle Kendrick, who also has a background in agriculture, or the media savvy of Precinct 4's Chuck Statler.

“The best part of the job is the people that you meet, the people you come into contact with, without a doubt,” Bolls said.

The worst part of the job, he said, is the approach that the legislature has taken to working with counties, including commissioners' continuing nemesis, unfunded mandates.

"Of course, they'll tell it differently," he said. "But I think there's a general lack of respect for counties at the state level.”

Bolls admits, though, he’s been happy to participate in even arduous tasks, such as setting the yearly budget.

“I know that sounds kind of crazy, but I like getting the numbers,” he said. “You learn real quickly how counties work. I wish we didn’t have some of the challenges we have, but I enjoyed doing that work very much.”

Bolls did note his budget work showed him the law of diminishing returns is real.

“You can cut and cut and cut, and pretty soon you start to cut into central programs,” he said. “You don’t want that to happen.”

A good return

Under Bolls’ tenure a $55 million bond was passed for repairs and new construction at the Taylor County Expo Center.

“I think people sometimes expect a lot more of us than what we're capable of doing,” Bolls said of county government. “We have a lot of critics out there who think we're not doing a very good job, period.”

But projects like the Expo Center, which greatly expanded its space and capabilities, help him feel the county gives taxpayers a “pretty good return” on money spent.

That said, it’s always wise to listen to taxpayers’ concerns, he said, and to make sure that they’re involved in the process, something Bolls has always said he wants more of.

It requires an open phone line and an open mind, he said.

“We do the best we can, but we don't have all the answers, either,” he said. “It's why we like to get input from the public.”

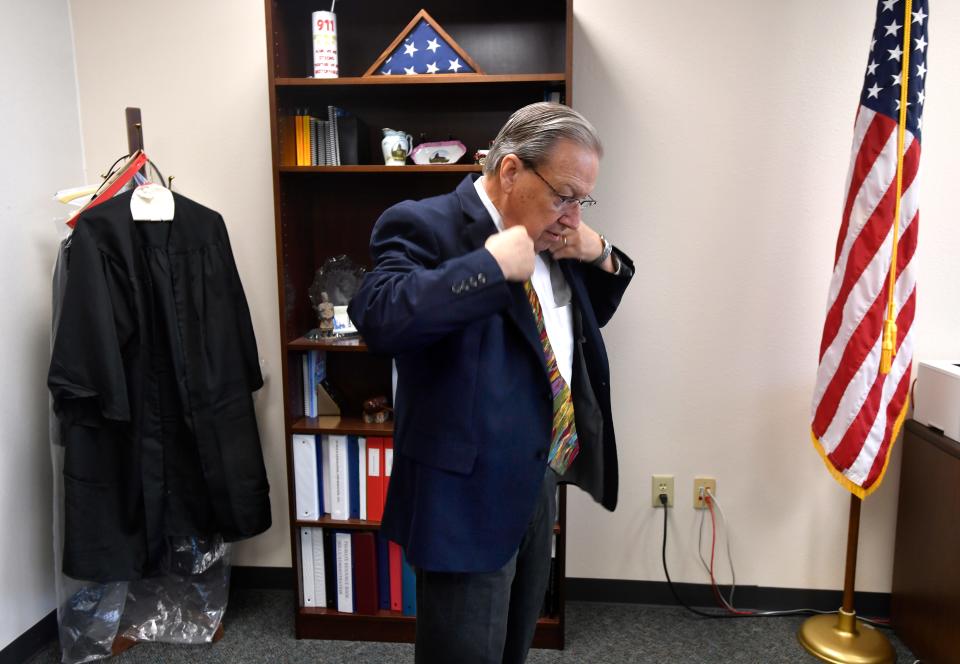

Making history

His respect for the present has driven side-by-side Bolls’ enduring love for the past, and under his tenure the county has focused on preserving the courthouse built in 1915.

Costs have escalated on the project, driven in part by supply chain issues and construction costs, part of the cost will be paid for by a state grant.

But Bolls believes the investment will be worth it.

“We've lived through this part in this town where we were tearing down our history,” he said. … “People will get a chance to go into this building and step in there and step back into history when they go in and see the way it was in 1915, when it was brand new and just been opened up.”

For his preservation work, the Taylor County Historical Commission honored Bolls this year with the Maxine Perini award.

The award, first given in 1995, recognizes outstanding service in preserving Taylor County history and promoting historical events.

It's yet another accolade Bolls can add to an impressive stack, including a recent "Citizen of the Year" award from the Abilene Association of Realtors.

Let the music play

While there's plenty of options for future contributions, Bolls plans to take some time to listen to life's music − and to continue to make some of his own.

As a teenager growing up in the era of the Beatles, Bolls figured out playing guitar wasn’t a bad way to get girls to pay attention to you, he joked.

“I couldn't play football. I was too little to be a football star," he said.

So like many, he started a garage band, getting popular enough to play dances and earn cash to buy additional instruments.

Bolls learned basic chords from his father and regards his dad as the “muse” that inspired him.

“When I have a down day at work or something else like that, I'll go home and sit down for about two or three hours and play the guitar,” he said.

He enjoys playing at Brook Hollow Christian Church, where he and Debbie attend.

A new voice

He might return, at his wife’s urgings, to something resembling his radio roots – podcasting – at some point in the future, perhaps about the “real story about county governments,” he said.

"I actually bought him a podcasting setup last Christmas," Debbie Bolls said. "It's not out of the box yet."

But she said her husband has written so much over the years and is replete with short stories, vignettes and historical analysis on everything from previous county judges to historic places and events.

"And he's got the voice for it," she said.

Bolls said he also has grandchildren to visit and a fishing pole in the garage.

“You look forward to retirement, but I’ll stay active,” he said. “There are a lot of opportunities for people to volunteer and do things.”

The real deal

While those in official positions help, it’s the “real people” who work in the county who make it truly run, he said.

“You want to know who the real people are that matter in this community? It's your moms and dads. It's the people who go and work at the auto shop, or the people who work in the restaurants, the people who deliver food on the weekends and things like that," he said. "People are asked to serve in so many different ways.”

Debbie Bolls said her husband is "not really interested in a legacy," but more interested in being a good person, now and ongoing.

"He just wanted to do a good job," she said.

This article originally appeared on Abilene Reporter-News: From Marines to TV to government, Downing Bolls has seen it all