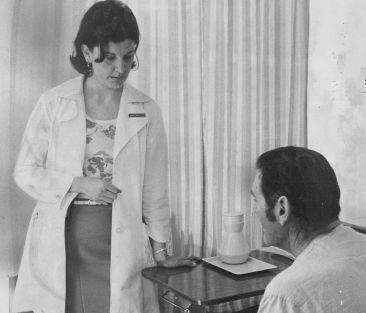

Marion Moses, Cesar Chavez confidant and expert on farmworkers' health, dies

When Marion Moses first met Cesar Chavez in Delano in California's Central Valley, he asked her: "What do you know about pesticides?" She answered: "Practically nothing."

In time, Moses went on to become the foremost expert on the health of the nation's 2.5 million agricultural workers beginning in the 1980s. She became an authority on pesticide poisoning of farm laborers, advocated for their healthcare and better working conditions and was leader of the nation's first medical study on migrant farmworkers in the 1990s.

But Moses was integral to the labor movement in more intimate ways. She was a close friend and the personal physician of labor and civil rights leaders Dorothy Day of the Catholic Worker Movement and Chavez, co-founder of the United Farm Workers union. During Chavez's first 25-day, water-only public fast in 1968, Moses monitored the stubborn labor leader's health, even insisting that he allow liquid minerals in his water to prevent organ failure. She took care of him for countless subsequent fasts, including his last in 1988, which lasted 36 days.

Moses was also there at the picket lines and helped direct grape boycotts in Philadelphia and Montreal. In the late 1960s, Chavez sent her to New York to boycott grape shipments to the East Coast and raise money for the perpetually cash-strapped union. Chavez came to trust her with the hardest jobs because "he knew she could handle them," said her brother Maron Moses.

"Marion was very abrupt, bright and very direct," he said. "She had a really abrasive personality and said exactly what was on her mind... Her middle initial was a 'T,' and no one would ever mistake that for 'tact.' " But those who knew her said she was kind and cared genuinely for others.

Moses died of natural causes on Aug. 28 in San Francisco. She was 84.

UFW mourns the passing of Dr. Marion Moses who turned a weekend in Delano into a lifetime of service helping Cesar Chavez, farm workers combat the perils of pesticides. Read more @ https://t.co/Dfz7LilZqW pic.twitter.com/34NUOfBCN6

— United Farm Workers (@UFWupdates) August 29, 2020

It was October 1965 when Moses met Chavez at a meeting in Northern California. A voracious reader and Shakespeare enthusiast, Moses was a student at UC Berkeley studying for a master's degree in English when she saw a notice on a campus bulletin board: the United Farm Workers union needed medical volunteers.

With a master's degree in nursing already under her belt, she drove to Delano for a weekend. She stayed five years, working as an organizer, volunteer nurse and healthcare administrator for the UFW. She was paid $5 a week and provided room and board.

"I'm a very pragmatic, task-oriented person," Moses told The Times in 1984. "I'm not very abstract. I thought: 'These people are suffering. They've got no toilets, no running water.' I thought I could stay and make a difference."

In an article she wrote for The Catholic Worker in 1993 following Chavez's death, Moses said that she left the UFW in 1971 to become a doctor. It was a move inspired by Chavez's question years before about her knowledge of pesticides. When she returned to work for the union from 1983 to 1986, pesticides were a prominent part of her work.

"Working with the UFW meant extraordinary personal demands and sacrifices, and the need to sustain a high level of commitment over the long term," she wrote. "The inspiring and the lofty were mixed in with a much greater amount of the tedious and mundane. It was not always easy to adjust or sort it all out, and over the years, many left the union in varying stages of confusion, bewilderment, or turmoil."

Marion Theresa Moses was born in Wheeling, West Virginia, on Jan. 24, 1936. Her family moved to Charleston, where her mother was a homemaker and her father a food salesman. The couple raised their eight children in a modest Catholic home. When Moses was 7, her baby sister Margaret Rose died of dehydration after suffering from diarrhea.

It devastated Moses. "She knew things like that didn't need to happen," said Maron, her brother. But it fueled her drive to become a doctor — a medical path her father deemed unsuitable for a woman.

Marion Moses was a remarkable woman, smart, fearless, passionate. She made a difference. For so many. https://t.co/ummPuFGf32

— Miriam Pawel (@miriampawel) August 29, 2020

So to nursing school she went. Moses earned her bachelor's degree in nursing from Georgetown University in 1957. She was the first in her family to go to college.

She went on to earn a master's in nursing at Columbia University Teachers College in 1960 and taught at Charleston General School of Nursing before moving to San Francisco. A job as head nurse in the medical and surgical unit at Kaiser Foundation Hospital awaited her.

But it was her work with Chavez and UFW that changed the trajectory of her life. Though Moses once admitted she was unimpressed by Chavez as a speaker, she was drawn to his "strong moral force" and his charisma. Their relationship solidified when Moses and President Kennedy's physician Janet Travell helped a bedridden Chavez slowly recover from severe back pain.

"She was pretty strong-willed," recalled Chavez's son Fernando, who met Moses some 50 years ago when she was a volunteer nurse in Delano. "It was not uncommon for her to have disagreements with my father about how to do and run things, and he respected her for that." Moses would become the "family doctor" for three generations. When someone fell ill or needed a second medical opinion, they'd call Dr. Moses.

Moses met feminist leader Gloria Steinem in 1968 during a trip to New York for a union fundraiser that included comedian Mort Sahl, the folk trio Peter, Paul and Mary, and others. Steinem learned that Moses was staying in a small dormitory, so she offered her her space. Moses slept on the activist's couch for several months; they became lifelong friends.

Together they picketed supermarkets, held benefits, organized consumers and even helped get Chavez on the cover of Time magazine, Steinem recalled.

The late ’60s was also when the labor movement was gaining attention outside California. Moses, in many ways, was the bridge between the farmworkers' union and New York's intellectual community.

"She was very brave," Steinem said Thursday. "She was often the only woman doing the kind of work she was doing. She wasn't herself a farmworker, but she fought fiercely for farmworkers."

Through her work, she dedicated her life to standing up for and advancing "justice and compassion," she said.

"The courage and conscience she modeled have influenced the rest of my life," Steinem said.

Despite the indispensable roles she had within the movement, Moses still dreamed of becoming a doctor.

She returned to Berkeley for a pre-med degree before enrolling at Temple University School of Medicine in Philadelphia. Medical schools were male-dominated spaces in the 1970s, and it was customary for professors to invite bikini-clad models into the first day of anatomy class to examine their physical structures.

"Let's just say that was the last time that ever happened," Maron said. "She went into the dean's office and said: 'I did not go into the medical field to watch a striptease.'"

From 1983 to 1986, Moses worked as medical director for the UFW in California, where she helped discover cancer clusters in small farm towns like McFarland, outside Bakersfield.

"Her commitment to farmworkers was way beyond professional," said Monica Moore, co-founder of the Pesticide Action Network who worked with Moses in the late 1980s. Together they launched a survey to analyze what farmworkers knew about the pesticides they worked with. "For her, the work she did was personal, spiritual. Her passion ran deep and very, very long.

"She just wanted to make sure that people's lives were considered."

In 1988, Moses founded the Pesticide Education Center in San Francisco. She served as director until her retirement in 2016, following years of advocacy, research projects, testifying at congressional hearings and more.

Despite her accomplishments and consequential roles in the farmworkers' movement, Moses felt it wasn't enough.

“I think she’s sorry she didn’t do more," Maron said. "She was really concerned with farmworkers, with the use of pesticides, knowing how devastating it was to their health."

Moses never married or had children, but she had "lots of kids," she once said. She considered the farmworkers her family.

"The way I look at it, there are all these wonderful things that people could do to help other people, and if they did, they'd feel a whole lot better about themselves," she told The Times.

When she returned to UFW as a newly minted doctor, Chavez asked Moses how long she planned to stay.

She replied: "As long as it takes."

Moses is survived by five siblings, Marcella, Martha, Maron, Martin and Marlene.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.