A maritime link to the Underground Railroad? Exhibit explores the role of whaling ships

NEW BEDFORD — “I wonder what kind of hope and promise they saw from a federal government that sold human beings,” said Lee Blake, president of the New Bedford Historical Society, about enslaved people who made their way North to find freedom.

Her great-great-great grandparents fled Virginia with their children in a way that seemed so clever, and is only recently getting recognition by historians.

History speaks of enslaved people who found their way to freedom by means of the Underground Railroad — a network of safehouses, called “stations,” where the escaped slaves would take shelter as they made their way to Canada.

The quieter side of history tells of those enslaved who found freedom another way — by sea.

“Both of my great-great-great grandparents escaped slavery from Virginia and came to New Bedford by ship with their children,” Blake said, relaying that Amelia Piper and her husband, William, snuck aboard a whaling ship in Alexandria, Virginia, with their four children in tow.

Path to freedom: 6 New Bedford homes used by enslaved people escaping via the Underground Railroad

Whaling Museum exhibit explores maritime link of Underground Railroad

"Sailing to Freedom: Maritime Dimensions of the Underground Railroad" is on view at the New Bedford Whaling Museum until Nov. 20.

Marcus Rediker, professor of Atlantic history at the University of Pittsburgh and guest curator at the Tate Britain museum, opened the exhibit at a recent presentation.

“Thousands of ships came from the South shipping lanes, and all represented potential escape,” Rediker said. Enslaved people who worked on whaling ships in the South would gain seafaring experience and the captains who were abolitionists would hide them aboard their vessels.

“I learned about them when I was about 14 years old,” Blake said of her great-great-great grandparents coming to New Bedford sometime around 1826 to 1830. However, she didn’t find out until she was older that they had made their journey by boat.

Park moving forward: Long-awaited work begins on Abolition Row Park in New Bedford

Enslaved people who fled the South by merchant ships didn’t talk about how they escaped, Lee said, because some feared for family members left behind or feared they would be recaptured.

"It was a secret," she said.

How the Piper family came to board a merchant ship was likely because the two sons, Robert and Philip, who were 14 and 12 at the time, worked on whaling boats in Virginia. Blake surmised that they got to know which captains were sympathizers who would help them escape.

“I think about them living in Alexandria where the selling of slaves was predominant,” Blake said. “What they must have seen.”

Blake said family lore believes the Pipers sailed to New Bedford aboard a schooner owned by the Rotch family. Rotch is the name recognized today as being attached to the Rotch-Jones-Duff House & Garden Museum on County Street.

What surprised Blake was that the Pipers sailed to freedom as a family.

“They all came together and not everyone was able to do that,” Blake said. Those who escaped over land sometimes had to travel alone before other family members could make the journey. “They came up in dribs and drabs.”

Also traveling over land through the Underground Railroad took a very long time, while traveling by ship only took a couple of days.

Virtual tours, 'sight unseen' purchases: Remote homebuying trend stays strong in Mass.

What happened when they reached New Bedford

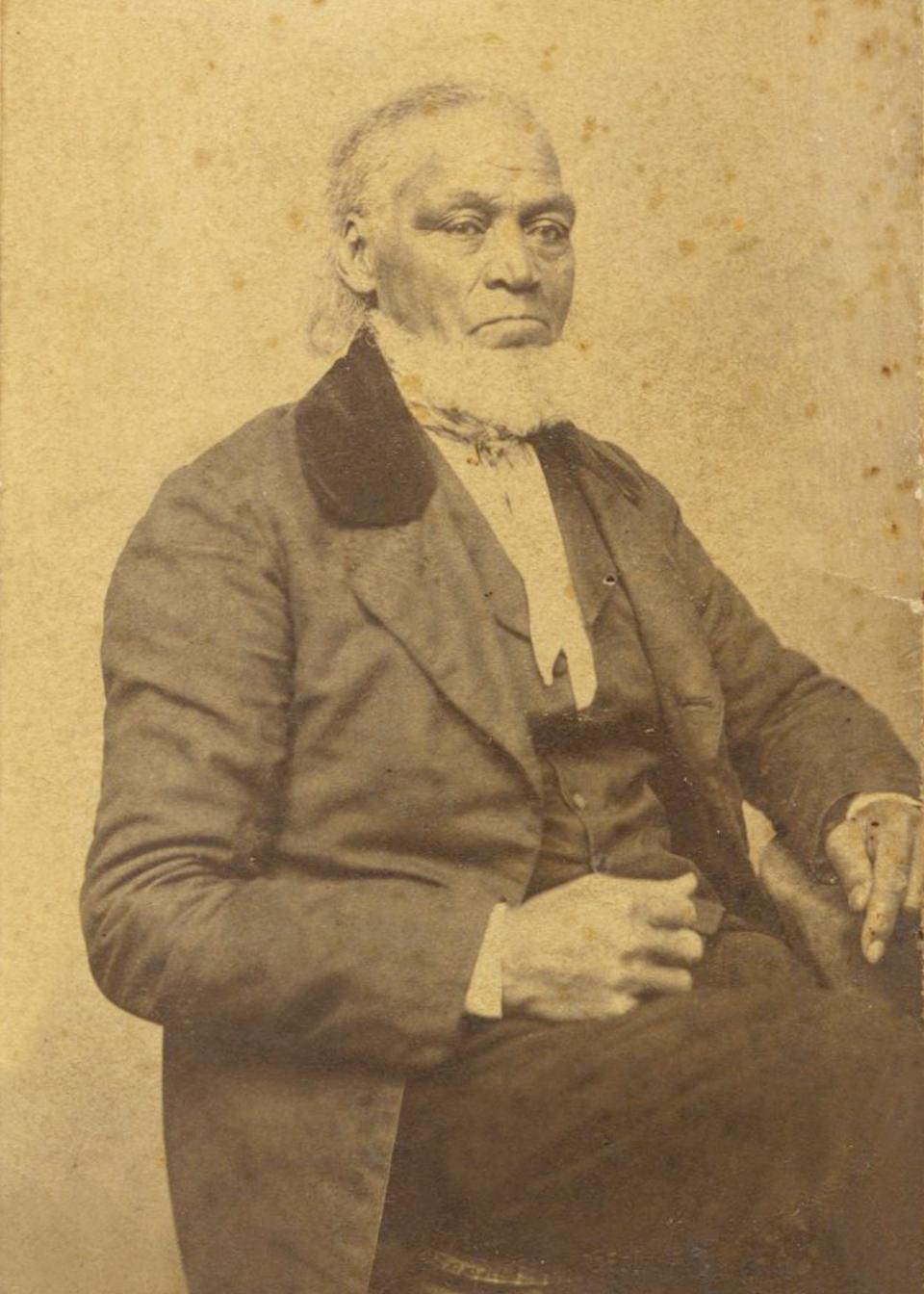

When the Pipers arrived in New Bedford, they worked for William Rotch Rodman. They would go on to help other fugitive slaves coming to New Bedford including John Jacobs, brother of Harriet Jacobs. He would later travel with the famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass. The Piper family served as a go-between for John and his sister, writer and abolitionist Harriet Jacobs, while he was out to sea.

The Pipers were the first members of three generations of a family that were active abolitionists and Underground Railroad activists who fought for the end of slavery in the United States.

“We meet regularly twice a week, ply our needles and fingers, talk over the wrongs of our countrymen and women in chains, and pray that the time will soon come when every yoke shall be broken — when all oppression, (whether it be southern slavery of northern prejudice,) shall cease in our land and the world.”

Those words appeared in the 1839 issue of The Liberator, a weekly abolitionist newspaper, announcing the New Bedford Female Union Society’s intention to hold an Anti-Slavery Fair in New Bedford.

Amelia Piper was one of the managers of the group.

Major funding for the "Sailing to Freedom" exhibition was made possible by the National Endowment for the Humanities through a National Writing Project “More Perfect Union” grant and the New Bedford Historical Society.

The curators are Michael Dyer, NBWM, and Timothy Walker, UMass-Dartmouth.

Download our app! Standard-Times digital producer Linda Roy can be reached at lroy@s-t.com Follow her on Twitter at @LindaRoy_SCT. Support local journalism by purchasing a digital or print subscription to The Standard-Times.

This article originally appeared on Standard-Times: Exhibit: Slaves escaped to freedom in New Bedford via whaling ships