Mark Woods: 60 years after March on Washington, A. Philip Randolph's story — in his words

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

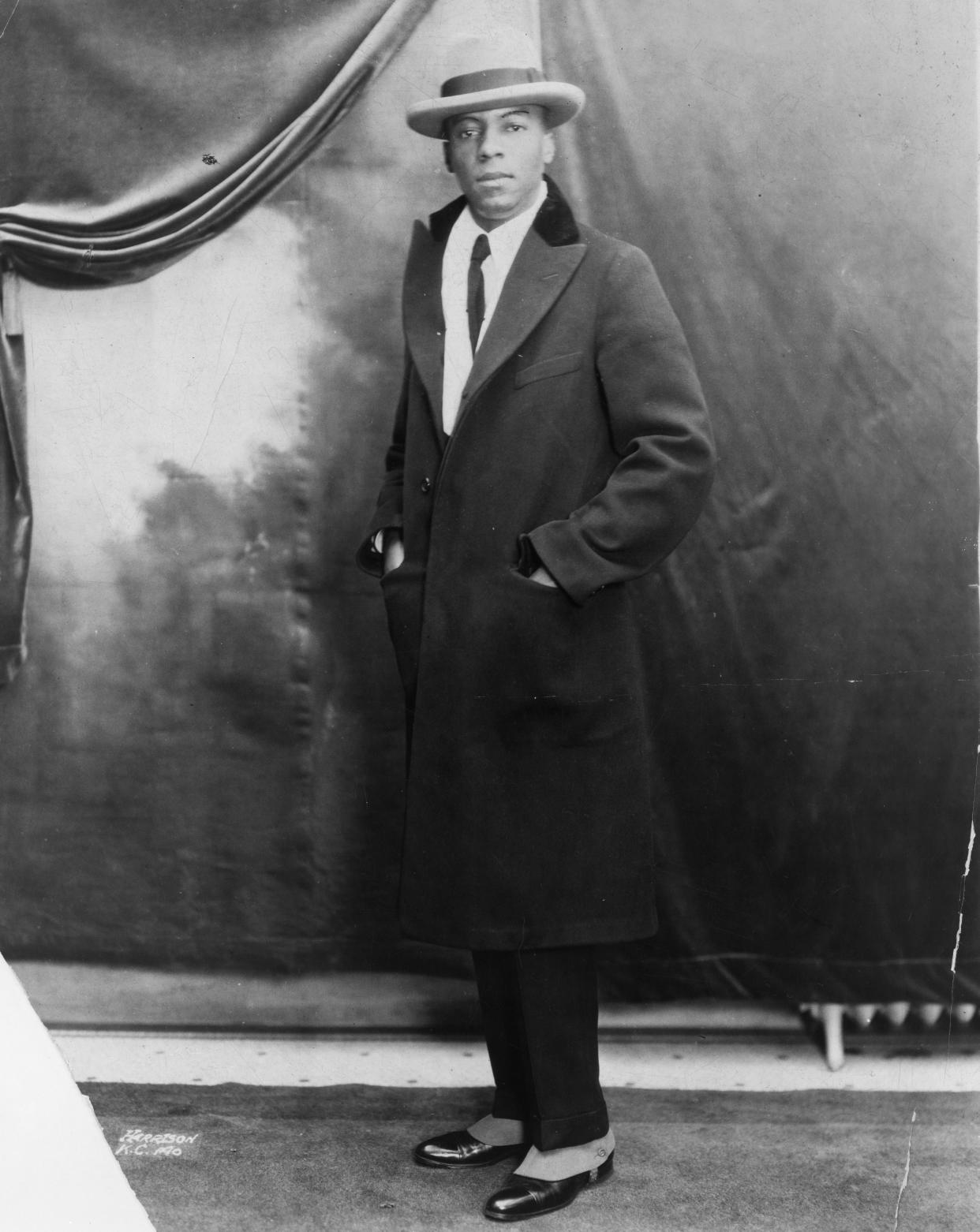

For someone looking for original material about Jacksonville’s history, it was like stumbling upon a treasure, not exactly buried, but kept in the archives of a New York university: the transcript from a series of interviews conducted in the summer of 1972 with A. Philip Randolph.

“I wasn’t looking for this by any stretch of the imagination,” said Jennifer Grey, public services coordinator for Florida State College at Jacksonville’s library. “I was just poking around on the Columbia University site for something else. I did a keyword search for Jacksonville and went, ‘Hang on, there’s a 300-page oral history of A. Philip Randolph?’”

This discovery was part of the continuing research for a class, titled “History of Jacksonville,” that FSCJ professor Scott Matthews began teaching last fall.

Grey says that when they began working on creating the class in 2020, they planned to spend a lot of time getting their hands on archival material right here in Jacksonville. Then the pandemic shut down everything. In a way, she says, that was a blessing. It forced her to instead search digital archives, near and far.

That search eventually led to “The Reminiscences of A. Philip Randolph,” eight tape-recorded interviews conducted for Columbia University’s Oral History Research Office.

In 1973, the transcript was made available in the Columbia Rare Book and Manuscript Library, hundreds of pages, typewritten with handwritten editing.

Fifty years later, though, those same pages are available digitally.

“So I paid the $15 and got a PDF copy,” Grey said.

That transcript is particularly relevant now.

Aug. 28 marks the 60th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington. In the decade since the 50th anniversary, the last of the living speakers from that day — John Lewis — died at age 80.

So now it’s largely up to historians and heirs to tell the story of those who led the March on Washington.

Randolph died in 1979. His wife, Lucille, died in 1963, four months before the March. They didn’t have any children. And to a degree, historians often have overlooked his place in history. In a 2013 interview with the Times-Union, Lewis said: “I’ve always said — and it’s not to take away from the role of Dr. King or anyone else — but without A. Philip Randolph, there wouldn’t have been a March on Washington.”

Even in his hometown, Randolph often is overshadowed.

That’s one of the reasons Grey was excited to find the Randolph oral history — and to let others, including David Jamison at Edward Waters University (who is delving into Randolph’s connections), know about it.

“Every time a conversation comes up in Jacksonville about honoring a Black scion of the city, the only name that really gets raised is James Weldon Johnson,” Grey said. “And while James Weldon Johnson was incredibly talented — and absolutely worthy of reverence — he was not the only talented Black person to come from this city, not by a mile.”

He lost a job but found a calling

The 1972 interviews with Randolph were conducted at his home in Manhattan, 280 9th Avenue, a few blocks from where fellow March organizer Bayard Rustin lived at the time — and where, it’s worth noting, there now is a National Register of Historic Places plaque marking it as the site of the Rustin Residence.

At the time of the interviews, Randolph was 83 years old. It was nine years after the event that is often simply called the March on Washington, but officially had a longer title: the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

The interviews aren't about anything that happened that day in 1963. Not directly at least. They're about what preceded it in Randolph’s life — starting with his birth in 1889 in Crescent City, Fla.

Randolph tells the interviewer, Wendell Wray, that he doesn’t remember anything about Crescent City, that his earliest childhood memories are of Jacksonville — growing up on Jessie Street and riding the train to Baldwin, where his mother had family, or taking a boat to Green Cove Springs or Palatka, when his father was preaching there.

It’s clear that Wray, a librarian and educator who devoted much of his career to preserving African-American history through oral history, wasn’t familiar with Jacksonville. For instance, when Randolph describes Jacksonville at the turn of the century as a bustling city, a seaport with the St. Johns River running through it, Wray asks: “Is that navigable?”

Randolph says it’s not only navigable, the first time he went to New York City, he sailed there at about age 12, washing dishes in the pantry of a ship. He spent that summer living with relatives in Manhattan, including a cousin who was a janitor for apartment buildings on 89th Street.

He repeated this journey from Jacksonville several more times before moving to New York in 1911, settling in Harlem at the age of 22. And in hindsight, the experience of seeing the conditions for workers on the ships seems like one of the early sparks for what came later — from his successful drive to organize and lead the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters to the organization of five marches on Washington.

He recalls that during a trip on a steamship, he told other workers that they shouldn’t just accept the horrible working and living conditions. He told them they should demand changes, and if they didn’t get changes, they should go on strike.

He was fired from that job — but found a calling.

“That was my first introduction to the business of organizing labor,” he says.

A life shaped by Jacksonville childhood

As is the case with many oral histories, the stories sometimes meander and repeat and even conflict. But there still is tremendous historical value in being able to hear them told in Randolph’s own voice — a deep baritone notably tasked with delivering the speech immediately after Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963 — or to read his own words on the pages of the transcript.

A sample of a few relevant to Jacksonville (and what came after it for Randolph):

— Randolph, whose legacy became tied to organizing train workers, recalled how when he was a boy, a young man who worked on the trains would stop by the house.

“He’d come in his overalls … and we were all interested in getting him to tell us about his trips, about the train, what he did. He was a brakeman. … Our mother wanted to keep us away from any idea of ever doing anything like that, don’t you know. Working on the railroad, brakeman, fireman, switchman and so forth. She always wanted to think of us in terms of the higher educational activities.”

— He talks several times about loving baseball as a boy, wanting to go play it in the streets with other boys, knowing that would lead to trouble when he got home.

“I liked it and so did my brother, so we were able to have our own entertainment in our own yard. But we wouldn’t stay in our yard. We continued to go to the streets and our mother whenever she heard of us being out there, why, we were subject to chastisement, and sometimes we were given a little physical chastisement.”

— Joseph E. Lee, Jacksonville’s first Black lawyer, clearly made an impression on a young Randolph. He recalls going to Mt. Olive church with his mother and seeing Lee preach, and going to a political meeting with his father and seeing Lee, the customs collector at the port, speak.

“They had about 25 or 30 people on the platform. It was an open-air meeting. All of them were white except for one man. He was black and his name was Joseph E. Lee.”

— He describes his friendship in New York with another Jacksonville transplant.

“James Weldon Johnson was quite friendly with me because, I think, he was conscious of the fact that we came from the same place and that we happened to be in the same type of movement, although he felt we were far more radical than (NAACP publication) ‘The Crisis’ and the NAACP. But he wasn’t critical of that. I think he was glad that was the case.”

— He recalls the time his father left the house late at night, handing his mother a shotgun and telling her to protect the boys, then joining others to prevent a lynching.

He says his father told him and his brother: “The problem of one Negro is the problem of all Negroes, because there isn’t a single Negro in Jacksonville who has immunity from persecution from whites, and the persecution never comes by one white man, but it comes by mobs, and therein lies the major problem of our life.’”

He talks at length about his father, whom he describes as a modest, soft-spoken man who weighed about 140 pounds. He details how his father didn’t make much money as a minister — his primary church was New Hope on Davis Street — so to pay the bills he ran a tailoring business out of their house. And how his father passed along a love of books. And how he emphasized the need to stand up for social equality. And how that wasn’t simply about race, that people of all backgrounds were hurting.

On page 81 of the transcript — at the end of recalling some of what his father told him — there’s something that makes the interviewer ask: “Is that what he said to you?”

That’s right, Randolph says. Before he even started high school, his father predicted that someday people far from Jacksonville would know the name Asa Philip Randolph.

“He said … ‘I look forward to the time when your name will be nationally known around the country for the work you’re doing, not only for black people but for humanity.'”

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: A. Philip Randolph oral history 60 years after March on Washington