Mark Woods: A Pearl Harbor story. From Okinawa to Jacksonville with love.

At age 87, Shigeko Sams is old enough to remember Pearl Harbor. But her memories are different from most Americans who were alive on Dec. 7, 1941.

She was 5 years old, a Japanese girl growing up in a village on the islands of Okinawa.

Her parents owned a small shop. She remembers about a half dozen adults gathering there one evening. She overheard them talking, saying Japan was winning the war.

Eighty-two years later, she wonders how they even found out about what was happening on the other side of the world. They didn’t have telephones or televisions. And, of course, they didn’t know what was ahead, how the war eventually would come to Okinawa and leave a staggering death toll.

On a recent morning, Sams pulled out some photos from Okinawa as it is today, with memorials to Japanese and Americans, and with the kind of natural beauty that she says leads to it being called “the second Hawaii.”

If you look at what is happening in the world today and want a glimmer of hope that things can change, that people at war can someday be at peace, talk to someone who was alive when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and America destroyed Hiroshima.

And if you want to hear a story of how in the aftermath of intense hatred of people considered to be the enemy, two people found love, talk to Shigeko Sams.

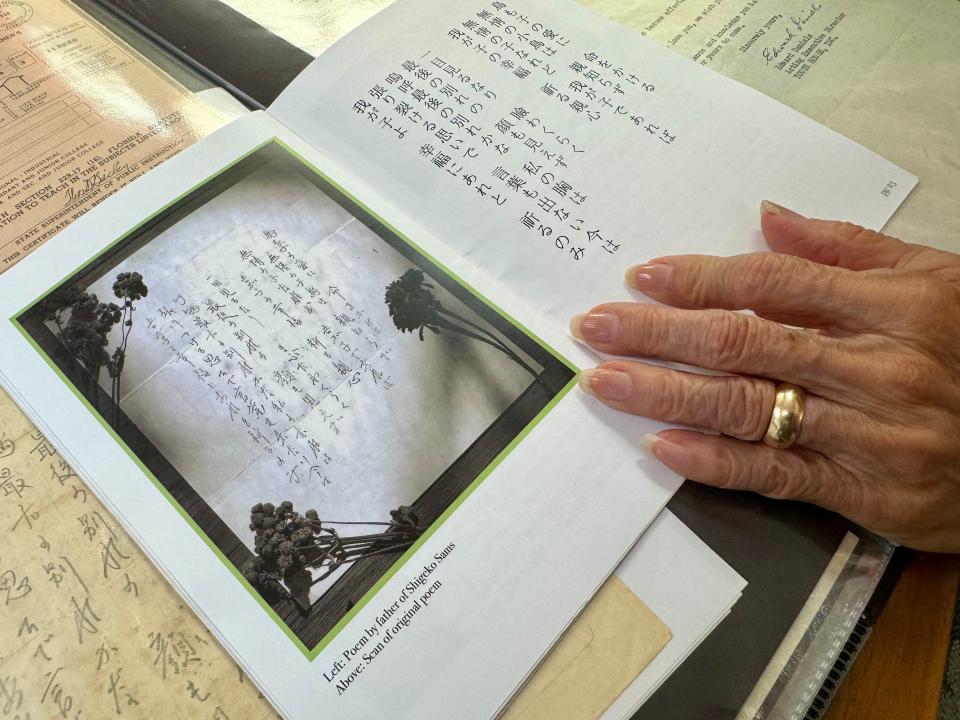

She opened a scrapbook full of memories from her life and spread them out on a table. Documents, letters, newspaper clippings. They help tell the story of how she ended up meeting a man from Jacksonville, coming to America, raising three children, opening a popular restaurant, managing the delivery of thousands of Meals on Wheels, earning awards for years of volunteer work.

But, first, go back to what happened after Pearl Harbor.

Preparing to fight the enemy

In first grade, she says they were taught how to escape, how to run and hide, how to sharpen bamboo sticks and charge at a tree that represented the enemy.

“Can you imagine?” she said.

Or maybe it doesn’t take all that much imagination. She recalls recently seeing images of war on the television, of children being trained to fight.

When she was in second grade, her family headed to China. Japan controlled sections of China, and the Japanese government was recruiting families to go there, to work in rice fields. Her father went first to begin building a house for them. Then one day her grandmother told her they were leaving in the middle of the night to join him.

She remembers some of the moments. Walking in the dark to catch a train, staying in a hotel, taking a ship to China, carrying her little brother on her back, standing in a field, seeing American planes fly overhead.

“In a way, we were blessed that we were in China during the war,” she said.

The Battle of Okinawa left more than 12,000 American troops dead and 36,000 wounded. It’s estimated that more than 70,000 Japanese combatants died. But the biggest death toll was of Okinawan citizens — more than 100,000 and perhaps as many as 150,000.

Leaving everything behind

When the war ended, Sams recalls that a Chinese government truck rolled up and they were told to get in. They were going back to Japan. They only could take as much as they could carry. They left everything else behind. Their house, their cow, their dog named Haru.

Even decades later, this childhood memory causes her to choke up.

“I still see my dog running after that truck,” she said.

They initially returned to mainland Japan, not the islands of Okinawa. While traveling on a train, they passed Hiroshima.

“I know exactly what it looked like after the war,” she said, describing the desolate landscape.

They eventually went back to Okinawa and she continued her education, through high school. This wasn’t a given, particularly for a girl. But her father recalled how his father had told him that he didn’t need any education, he was going to be a farmer. He didn’t want to do the same with his seven children. He told them, if they could pass the tests and he could afford it, he’d send any of them to high school.

He even made the chair and desk to take to school.

But when she graduated from high school, he couldn’t afford to send her to college. She heard about a typing school in a nearby village. That led to a civilian job at Kadena Air Base.

And that’s where she met Joseph Gardner Sams, Jr.

Kadena Air Base

Kadena, the site of an airfield used by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force, was seized by the United States during the Battle of Okinawa. It became a U.S. Air Force base and was reactivated for the Korean War.

Joseph Sams, who grew up in Jacksonville and graduated from Stanton High School, was stationed there with the Army. When the Korean War ended, he stayed in a civilian role, working in the main administration building.

Shigeko was working in a nearby Quonset hut. But sometimes Sams would come to get coffee. And one day he overheard a supervisor talking about some night classes Shigeko could take in Naha, a town about a half hour away.

This required riding a bus. Or getting a ride with someone who had a car.

Sams offered to give her a ride. On the way, he stopped at a restaurant and said, “Let’s get something to eat.”

She refused. She knew what locals would say and think if they saw her going in there with an American. They continued to her class. And when she came out of it, he was waiting to drive her home. She just got on the bus. That time. But after he did this a few times, she says, his persistence paid off.

On Feb. 6, 1958, they got married at the American Consular Office in Naha.

Her youngest sister knew about their marriage. But the rest of the family found out after the wedding. She remembers sitting next to one of her brothers on a couch. He took a knife and slammed it down into the couch.

“Not hurting me,” she said. “But he let me know what he thought.”

Her family was ashamed of her marrying a gaijin — a foreigner.

A father's letter

The night she boarded a plane headed to America, her father and younger sister came to say goodbye. Her father brought a letter.

She still has it in a scrapbook. She runs her fingers along the Japanese characters and gives a translation.

He wrote about how much pain this was causing him. He didn’t know if he’d ever see her face again. His heart was bursting. But, beyond the hurt and anger, most of all he wanted her to be happy.

She remembers her father saying to her husband: “Promise me you’re going to take care of my daughter.”

Coming to America — and going back to Okinawa

She says she was blessed. Her husband’s family — a family with deep roots in the city and its African-American history — welcomed her to Jacksonville. And while she has experienced a few chilly reactions from people through the years, for the most part, she was welcomed to America.

She knows not every Japanese immigrant could say this, particularly arriving just a decade after America rounded up Japanese Americans and put them in internment camps.

The Sams first went to Tallahassee, where Joseph took advantage of the GI Bill to graduate from Florida A&M. From there, they went to New York City, where he directed youth clubs and she became an American citizen.

She did see her family again.

In 1965, the Sams returned to Okinawa, this time with two sons — they’d later add a daughter — and to do mission work. A story that appeared in the Okinawa Morning Star said they had been sent there by the U.S. National Council of Churches, supported by the Episcopal Church. It added that the public was invited to a welcoming reception.

Shigeko Sams flips the scrapbook to some of the clippings from that reception. Read the cutline, she says. Their family was joined by all kinds of local dignitaries. She explains why this — both the return to Okinawa and this particular moment — was so important to her.

“It showed my family there shouldn’t be any shame,” she said.

When they returned to Jacksonville, Joseph Sams went to work as project director for the local Housing and Urban Development department. In 1973, they opened a restaurant, Super Chow — first on Davis Street, then in the basement of the old Gulf Life Building, and finally Edward Waters.

A story in the Times-Union said: “Even with minimal publicity (a few flyers at the start, then simply word of mouth), Super Chow’s growth took an impressive turn,” attracting a regular crowd of department store employees, business executives and city leaders like Mayor Hans Tanzler.

The appeal, the story said, was “a quality meal at an attractive price” — meat, two vegetables, roll, drink and salad for $1.40, a dollar less than most places — and the atmosphere. Intimate, friendly, homey, family-style. The Sams family.

They also won a Meals on Wheels contract and for years delivered 1,000 meals a day to area seniors and disabled people.

When Mr. Sams died in 1998, they had been married 40 years. She says he delivered on his promise to her father. He took care of her.

After his death, she decided to stay busy by focusing on her children, grandchildren and volunteering. She volunteered for about 25 different organizations, devoting hundreds of hours to the Sulzbacher Center and others, earning several awards — including one called the “Young at Heart” award.

Not that she was sure about any of this being a story, or at least one that appears in the newspaper. She explains that it isn’t in her nature. But eventually, she agrees. And when asked what we should make of Pearl Harbor more than 80 years later, she talks not only about her childhood memories, but about Okinawa today, with its sparkling water and beautiful coastline, and with memorials to Japanese and Americans.

mwoods@jacksonville.com, (904) 359-4212

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Pearl Harbor memories of Japanese girl who became American citizen