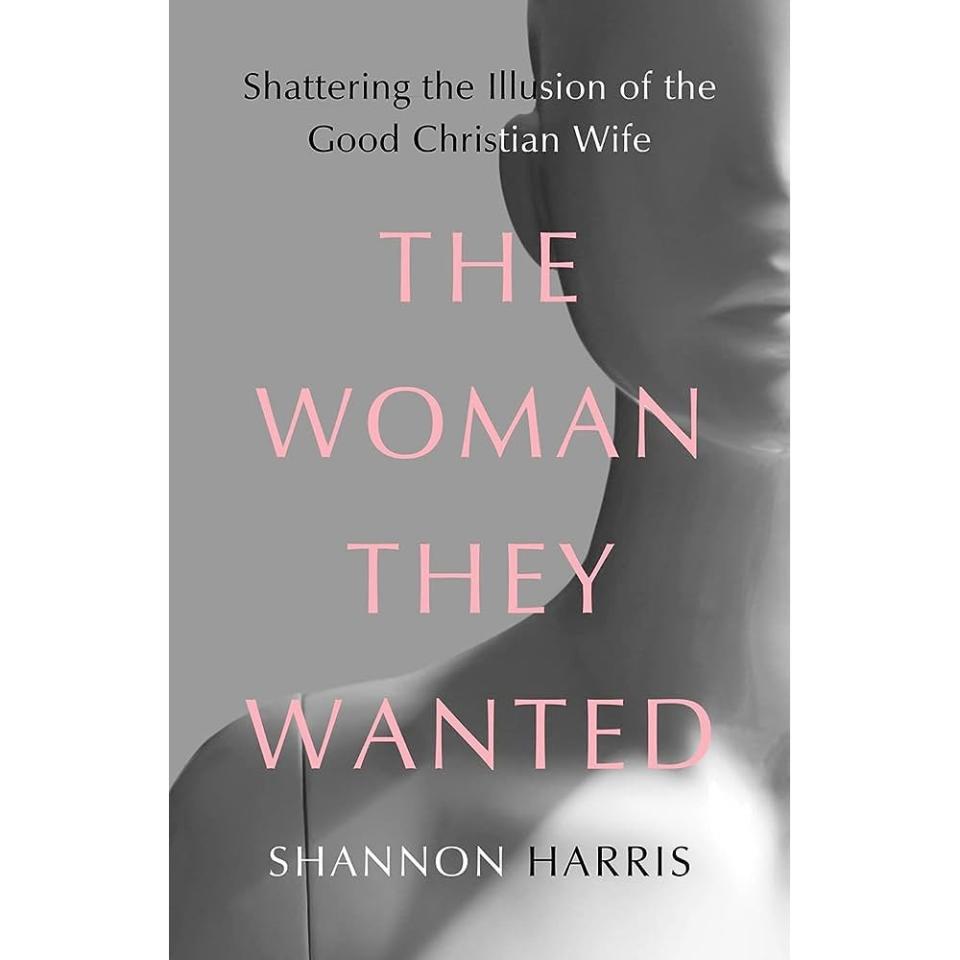

Her Ex-Husband Wrote a Hit Book About Abstinence. Now, She’s Telling Her Side of the Story.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For years, Shannon Harris’ church expected her to be an exemplar for submissive, biblical womanhood. She was married to Joshua Harris, the famed author of anti-dating handbook I Kissed Dating Goodbye, which sold over a million copies after its publication in 1997 and, in advising chaste courtship instead of dating, became a mainstay of American purity culture. Looking back, Shannon describes him then as a “kind of abstinence pop star.”

As Joshua’s platform grew, Shannon became a figure in his writing, sometimes deployed as a useful narrative device. He described her having a “typical party life” “ruled by sin” before becoming a Christian. She’d been headed to Nashville to pursue a dream of becoming a singer. But, as the story went, God upturned both their lives after Shannon joined the church and later caught Joshua’s eye. They wound up in a courtship, preparing for marriage in Maryland. The couple had to live up to Harris’ own relationship guidance. He later wrote how she “honored” his needs by dressing modestly and replacing a pair of shorts that caused him to “struggle” with lust.

Years after they wed, Joshua Harris became lead pastor at Covenant Life Church, the flagship church of international megachurch network Sovereign Grace Ministries (now called Sovereign Grace Church). Shannon gave up opportunities in order to fit herself into the church—recording for the church’s label instead of striking out on her own. And, of course, her days were full: She had to be free to homeschool their children.

What most of the world knew about Shannon was through this lens of salvation, submission, and her husband’s words. She worked hard to be—as the title of her new book outlines—The Woman They Wanted, even as she and Joshua had three children. But as Harris details, trying to embody what their church viewed as biblical womanhood was no dream. Their church started to fall apart in 2013, when C.J. Mahaney, co-founder of Sovereign Grace Ministries, resigned. As allegations of sex abuse and subsequent church cover-up continued to surface, Shannon was already in a deep depression. In 2019, via Instagram post, Shannon and Joshua announced their impending divorce.

Shannon and I spoke recently via Zoom about her life before joining her church, expectations of “biblical womanhood” (and how those requirements impacted her), and how she’s found herself again after it all. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Sarah Stankorb: I wonder if you can start by describing who you were, your religious roots before joining Covenant Life.

Shannon Harris: I was a very musical, artistic child. My mother was raised very strict Catholic, and she went to Catholic school, with the nuns and all that. She did not want to relive that experience with us or give that to us. My father had been raised Episcopalian. We would only go to church with my grandparents on Easter. Religion? My mother would say, “You can worry about that on your own later.”

What about your view of sexuality before joining Covenant Life Church?

I had a very typical kind of foray into sexuality. I explored around the same time as my friends. I would, you know, kiss boys. But I really didn’t like the impression the world has of me, based on Josh’s books, as some whore. It is absolutely so far from the reality.

The reality was I had like two boyfriends in high school. And one of those boyfriends was petrified of having a baby. Yes, I did lose my virginity in high school. But [sex] really wasn’t an important part of any of my relationships. It wasn’t until I had a college boyfriend that that relationship actually had sex as a significant component. So then that was it. And I met Josh after that boyfriend.

So, looking back, the perspective that was coming from the Christians in my life, that I had had such a dark, awful past, was such bogusness.

Did part of you see it as bullshit when Josh’s books were being written and published, or had you absorbed enough that you felt like you were as bad as the books described?

I think I was very divided. There was a sense in which I didn’t feel like I had been bad, that this was normal. And then there was another part that definitely absorbed the message of shame at some point, because that was the topic that got me on my knees to ask for salvation. But even when I was asking God for salvation and forgiveness for these sins, I don’t know that I completely bought into it.

I really remember getting the message that I had taken something away from my husband, my future husband, and that made me feel terrible. Like this was supposed to be protected, and I had failed to protect this thing. That was the concept that kind of ate me up—I didn’t know this was supposed to be a gift. And that, I felt shame for.

I want to talk through the roles of men and women’s submission, because not everyone is going to understand how relationships worked in your church—and many evangelical churches that practice what’s called “complementarianism.” How was that justified for you, coming from outside of a church like this?

For people that don’t know what complementarianism is: This is a theology that adheres dogmatically to a very specific interpretation of the Genesis creation story, which claims to support the idea that men and women are equal in worth but have differing roles.

So, the way it played out for me was that I would not have my own purpose. I was expected not to work; my job would be to support my husband fully, practically, emotionally, physically, sexually. The church was to be my everything.

You wrote very poignantly about women agreeing to these marriages “for better or worse” without a full sense for what “worse” might become. Can you talk about that a little? What don’t many women picture for their lives when agreeing to live in this sort of submission?

I want to preface this by saying that women in these churches are sold a message about what the husbands are going to do. The men were getting these messages also, that they were to love their wives as themselves; that they were to love their wives as Christ loved the church. They were supposed to romance their wives, schedule date nights, bring home flowers. Women thought that they were going to be these incredible husbands.

In the book, I talked about taking vows, “for better or for worse,” and the only thought I had about “worse” was cancer. I didn’t imagine that maybe I’d be unhappy in my marriage, and I didn’t understand the full implication of how biblical submission plays out in real life.

I do think it depends on the person holding the power, because the moment you say your wedding vows, the hierarchy and dynamic of your relationship changes. And suddenly, your husband has been given more authority, more stature, more respect, more voice, more financial security. You think it’s good, because you’re told that this is noble, you’re told that this is God’s way. You believe this is God’s good plan. You can’t imagine that your husband might be manipulative or might fall apart and stop leading. You don’t imagine maybe you’re going to feel lonely, abandoned with the kids.

There’s just a humongous gamut in these marriages. Maybe your husband becomes an alcoholic later. Maybe he starts hitting you. You’re not expecting any of those things. You’re expecting things to go great.

The way you describe falling into your “helping” role with your (now ex-) husband Joshua, it sounds very familiar, almost a living version of “… and his lovely wife.” Can you describe moments spent in that supportive, smiling, mostly quiet role, and what that did to your own sense of purpose? Your own dreams?

It felt very uncomfortable. I described in the book the first time Josh invited me up to the front at one of his conferences. I stood there for two or three hours while people, mostly women, were coming up to him and talking to him about their response to his book, and I remember how useless I felt. I think that was one of the few times I actually was like, Do I want this? Am I really going to do this? But I reasoned with myself that, surely, it’s not gonna be like this all the time. I think I genuinely did not think biblical submission was going to be oppressive in the way that it is.

But I love the fact that you mentioned my dream, because I really did want to kind of have that thread going through the book. I stuffed my dream, and I embraced this role. I think there were times I was doing really well with it. I tried. But something would always happen that would kind of snap me out of it. And I’d be like, What am I? I’m not really happy. And then I’d have to re-up my commitment to this model over and over and over again.

As time went on, the exhaustion grew. And I did realize this part of me, this dream I have, that I had a purpose inside of me. I knew I was supposed to use my voice somehow. So I think it’s super crazy that I got into a setting where I literally had almost no voice. And that was a very, very painful and very difficult thing for me to get back.

After a while though, it’s your whole community. You describe how while C.J. Mahaney mentored Joshua Harris as a pastor, his wife Carolyn mentored you, teaching you how to be a pastor’s wife in this environment—which required learning to manage a home, but also to sacrifice. I wonder how this impacted you.

There’s a real handed-down kind of mentality in this culture. The women in your life are reinforcing this. I had a friend who actually was told almost the same thing as me. Carolyn, my mentor, had given up her dream. And so I had to give up my dream. And my friend that I met, she said her mentor had given up her dream of being a teacher, and when she was mentoring my friend, she said: So you have to give up your dream of being a playwright. I think women are a strong reason why it continues.

I want to talk about the guidance to initiate sex in order to resolve marital troubles, if you are comfortable discussing this. It’s advice I’ve heard women repeat all across evangelical spaces. In general, women have told me how that mandate or “encouragement” only makes them resent their husbands and certainly not enjoy the resulting sex. Can you talk about the responsibility this places on women? What does it feel like to have a trusted mentor take you aside and give this guidance?

I mean, it’s not just sex, but from the letters I’ve received from women after leaving the church, who’ve been hurt in their marriages, it seemed like they were the fixers of all the problems, and always either had to forgive or accept—and sex was a part of that as this remedy. But it seemed like overall, women are called to hold up the marriages.

I feel like I learned some things after I left. I didn’t understand the culture of abuse and the way that biblical submission creates and nurtures an environment that is welcoming to abuse until after I was out. I didn’t realize that women were being called upon in these private meetings, where they were experiencing abuse, to forgive their abusers. And where children who are being abused had been asked to forgive their abusers and face their abusers. That was all new to me later. [Here Harris refers to allegations like those raised in a 2012 class-action lawsuit against Sovereign Grace Ministries and some of its leaders. The lawsuit was dismissed on technicalities, including Maryland’s statute of limitations for bringing civil suits in matters of child sexual abuse, in 2013.]

Now for me personally, this was one area where I was actually disobedient. I did not actually do what I was supposed to do in this area, which is really kind of interesting to me. The flip side is that also I did not feel traumatized sexually, at the end of the 20 years, in the same way that I did emotionally, psychologically, and personally, and I think that’s fully because I didn’t actually do what I was supposed to do.

I tell the story in my book about Josh and I having our first fight and how, in the midst of that fight, he called Carolyn and C.J., and they came over to help us with the fight. And we had a discussion about our argument, and they shared about their conflicts, and how they kiss and make up. The next day, I was homeschooling two kids, and I had a little toddler, and Carolyn called me and specifically asked me if I’d been initiating sex with Josh. And it was like, very pointed. Right to the point. This fight, she was inferring or insinuating that I’m responsible to fix. It was definitely a WTF moment for me.

And I said, No, I’m not. I don’t like it. And I look back on my time, and that was one of the most truthful times I ever had at the church. We did have sex regularly, but I did not do my job and initiate. I initiated only once in 19 years.

Wow. But at the same time, being told that you need to—I think I understand how someone putting the pressure on in that direction would be repellant.

I was really repelled by her comment, and it had the opposite effect. I was like, I’m not doing that. But I also think physically [given strict purity culture], we didn’t have the chance to kind of discover our relationship, and I think that there was a piece physically that—the chemistry wasn’t quite right.

Your church went through great turmoil while Josh was still lead pastor, between Mahaney stepping down in 2013—after huge email and document dumps detailing his resistance to correction or checks on his influence—and allegations that also surfaced that church leaders mishandled various instances of abuse, including knowing about abuse claims but not reporting to police. Did that period rock your faith in the church?

I was already doing so poorly, struggling from under the weight of this doctrine. For years prior, Josh was coming home saying there’s all this tension with the leadership. For me personally, by the time the documents came out, I was not in the state to be able to fully engage in any of that. I didn’t read the documents, and I didn’t read the allegations of abuse until the time around writing my book. The reason for that is I was dealing with my own personal trauma. Then the documents came out and my whole world crumbled in an instant. C.J. cut ties with us and made sure others did too. There was no grace or sense in it. And I think that was what rocked my faith.

But if you’re wondering if I ever knew of any abuse and didn’t report it, the answer is no. People have come forward [since] that I knew, and that’s just brutal. I knew people who were being hurt. I believe my story is part of a larger story here, and I’m really concerned about what has not been uncovered, and I hope that someone is working on this.

I also wanted to ask about your depression. From the time you joined the church, you were under pressures to be modest and lead by example as a singer on the worship team, then there was the push to conform to the church’s expectations of womanhood. Years on, you described in the book how you sat in bed for a year. Where does all that fit into the timeline with allegations and turmoil at the church?

[Depression and anxiety] had started in Maryland [around 2009] and continued. It was really long. I’m honestly just kind of coming out of it really well now. But it’s been the better part of a decade. It was hard. I was particularly isolated because everything changed. [After leaving our church in 2015,] we moved [to Vancouver], and I didn’t have the same kind of connection and community around me, but I did have some trusted friends here, and my mother was there for me.

There was this real Barbie moment—you know, the movie? The moment where the Barbies are waking up, and they snap out of it? I remember having that moment. That was the moment where I realized, wait a minute, this biblical submission thing—this wasn’t good for me. This wasn’t for me. This was for them. This was for their benefit. They are asking me to live in this little tiny box and be happy there. And it’s for their convenience and has nothing to do with being for my well-being. When I snapped out of it, the first question I had was, Why was I there for so long, and not able to see that this was not for my good?

What I realized is that I froze. So, I was dealing with a lot of trauma [resulting from those early years in the church]. When you can’t integrate a traumatic experience, you fight, or you flee, or you freeze. I froze. I couldn’t make sense of it. And then I basically got married as a frozen person. And some of these events I couldn’t make sense of keep happening. And now I’ve just gotten used to not making sense of anything. And I’m basically living in a frozen state, I don’t know what to say, what to do. I don’t respond, because none of it actually makes sense. And that’s how I ended up getting stuck for 20 years.

I also wondered who your ideal reader is—who are you trying to reach that would make all this introspection worth it?

On the one hand, the person I was thinking about the most in my heart when I was writing would probably be the women who got married during the purity movement, and maybe were put in their marriages and in harmful situations. So, trapped women.

Also, this reader’s probably not going to happen, but I think I would love church leaders to read my book, male church leaders, because I think they need to understand and listen to women’s experience in order to move forward with their churches. I wanted to create a book that they could learn from if I could get some of them to read it.

And then I think on an artistic level, I just wrote to be creative. I am really excited to make things, to create things. I like being the person that’s creating stuff and making stuff. I wasn’t allowed to do that in the church. It was always the men. They were writing the music. They were writing the sermons.

I have to say, I’m kind of ready to move on to a different topic, though. I think my next goal is to write a one-woman musical comedy. That’s where I’m going next.