Martin Luther King Jr.'s 1957 Tennessee visit sparked a movement - and rankled the FBI

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

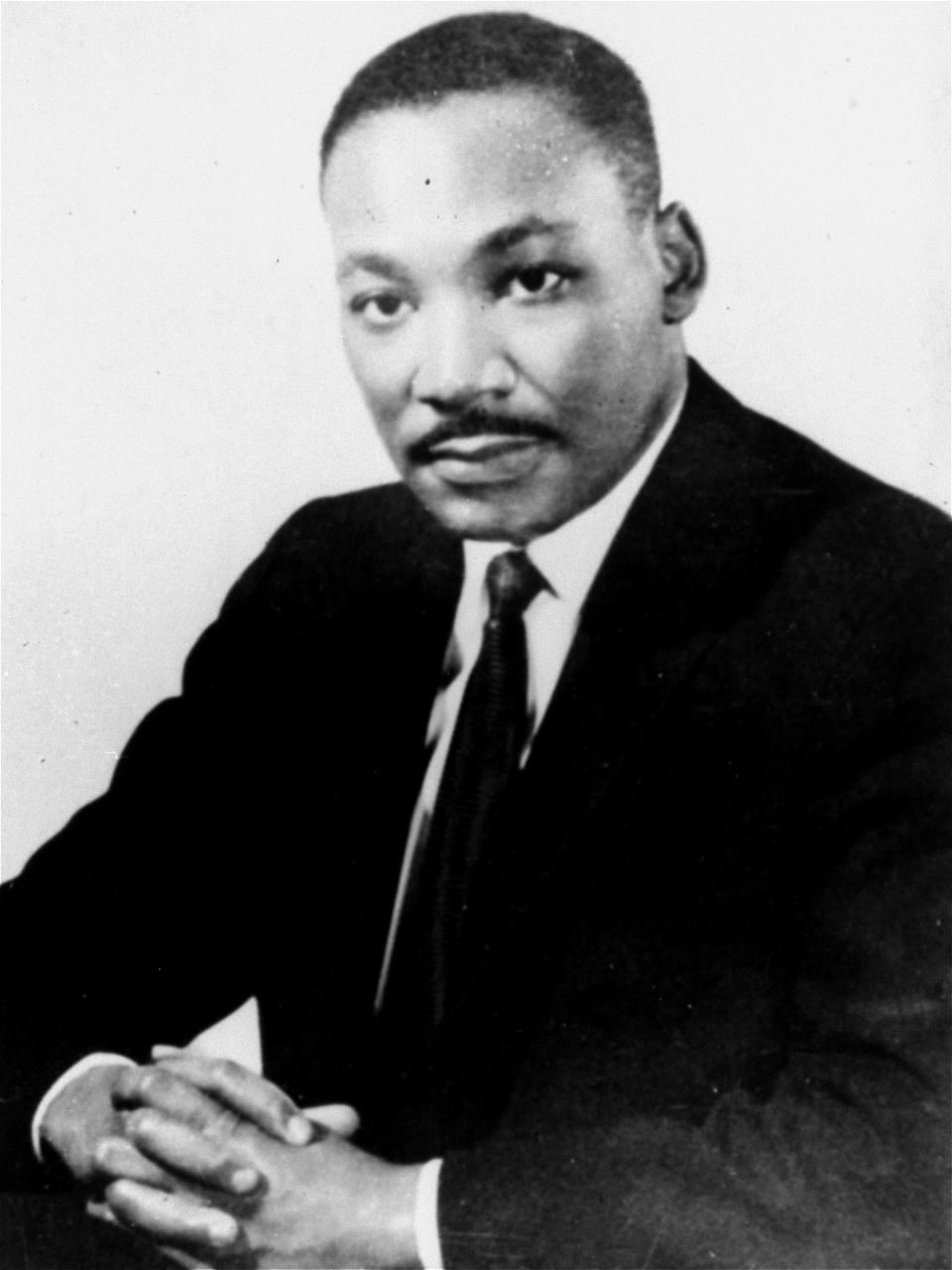

He had a dream. But years before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stood gazing into the sea of onlookers stretching out from the Lincoln Memorial, he assured a room of organizers in Tennessee that segregation would finally come to an end.

He was only 28 years young but highly educated, a Morehouse College graduate who had finished seminary and received his doctorate from Boston University.

“We have broken loose from the Egypt of slavery. We have moved through the wilderness of 'separate but equal' and now we stand on the border of the promised land of integration,” he said in 1957 at the 25th anniversary of the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle.

It was during that Tennessee visit that an ongoing FBI investigation ramped up in an effort to tie him to communism. It also could be considered the beginning of nefarious plans to annihilate King's dream of a racially equitable America, according to the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University.

His speech "The Look to the Future" lauded the work of Southern organizers, painted a harrowing reminder of the significance of the past and asked: Now what of the future?

In the crowd were Rosa Parks and King’s closest associate, the Rev. Ralph Abernathy.

“First, let us admit that the reactionary forces of the white South present certain barriers to integration that will make the transition much more difficult. They will seek to delay integration as long as possible by a variety of legal tactics,” King said.

“But in spite of all of this, the opponents of desegregation are fighting a losing battle. The Old South is gone, never to return again. Many of the problems that we are confronting in the South today grow out of the futile attempt of the white South to perpetuate a system of human values that came into being under a feudalistic plantation system which cannot survive in a day of democratic equalitarianism. Yes, the Old South is a lost cause.”

King’s invitation to speak at the Highlander Center followed a legacy

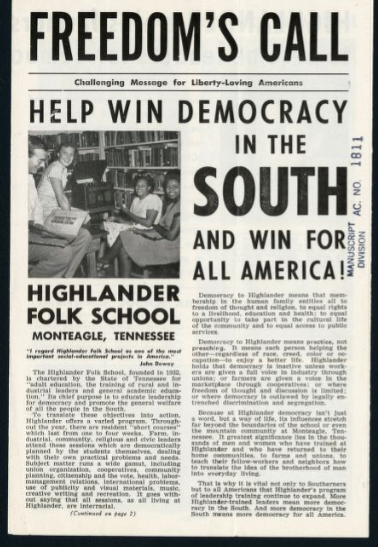

In 1932, Myles Horton and Don West founded the social justice training center in Grundy County, about 120 miles southwest of Knoxville on the Cumberland Plateau. The school's early activities focused on celebrating local culture and art, but it gradually moved toward organizing labor unions, civil rights and racial integration.

In 1953, Horton and the Highlander staff organized workshops on school desegregation a year before the doctrine of "separate but equal" was thrown out by the Supreme Court, according to Highlander Center Research and Education Center records.

“Dr. King was recognized as someone who by that point was kind of an up-and-coming young activist and established himself as an incredible thinker, scholar, preacher and prophetic pastoral voice to everyone in the South, and particularly the Black Freedom struggle," Highlander co-Executive Director Allyn Maxfield-Steele told Knox News.

"Highlander’s practice of pulling people together during our annual homecoming events usually includes a person of the time that can help speak to the moment and beyond it and there was no one better in that era of 1957 than Dr. King.”

Local and state officials railed against the Highlander for years before King's visit. Headlines from the Knoxville News Sentinel detail how a special committee of the Tennessee Legislature investigated the organization on loose charges of "race-mixing," communist ties and "un-American" behavior.

"This 'school' was not and is not a 'school' in the normal sense of the word," the committee wrote in a report. "No regular classes are held. ... The 'school' seems to be more interested in the questions that bring about community unrest and chaos rather than in the advancement of the science and arts of education."

Scrutiny grew after King’s 1957 visit. Individuals with the intention of spying also attended the conference, including Ed Friend, an agent of the Georgia Education Commission. Throughout the anniversary weekend, Friend tried to prove his point by trying to photograph Abner Berry, a writer for the Communist Daily Worker, together with King.

Friend published a four-page pamphlet titled, “Communist Training School, Monteagle, Tenn.” with photos of King and Berry.

The pamphlets were put out by the Georgia Education Commission in an effort to discredit King and the civil rights movement, and pictures of social events showing Black and white conference patrons dining and dancing together rang alarm bells in the racially segregated South.

“It was a ridiculous attempt to draw clear connections between those who might be involved in communist-leaning organizing and the Black freedom struggle because that was the greatest fear of most segregationists then and now, that is Black and white people getting together around class lines,” Maxfield-Steele said.

FBI investigation begins

The false allegations of communist ties between King and the civil rights movement continued after the 1957 Highlander conference, even leading to an aggressive FBI investigation. Wiretaps and paid informants were used to undermine and humiliate King following the March on Washington in 1963.

The director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, became obsessed with destroying the Communist Party and discrediting King's work.

In 1966, the wiretaps stopped, but the investigation continued until 1968 when Dr. King was assassinated.

After the Highlander visit, Knoxville became stopping place for King

King’s relationship with the Highlander Center continued into the 1960s, and in the years to come the relationship between Highlander and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference grew, according to the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Center.

Led by Septima Clark, Esau Jenkins, and Bernice Robinson, the Highlander Center developed a citizenship program in the mid-1950s that detailed to African Americans their full rights as citizens while promoting literacy skills. Southern Christian Leadership Conference organizers felt that the program became strong enough for them to take over the school’s citizenship education program after Highlander was harassed by the state of Tennessee in 1959, forcing it to relocate and change names.

In 1959, state deputies raided the school looking for evidence of communist propaganda.

No evidence of any crime was found, but local authorities discovered alcohol in Horton’s home, which was on school property. A Grundy County judge ordered the school closed, and its charter was revoked.

The school operated from 1961 to 1972 in a large house on Knoxville's Riverside Drive, changing its name to the Highlander Research and Education Center.

“The location in Knoxville was a resting place for Dr. King on his many trips throughout the South. He would stop at Highlander when he came to speak or visited East Tennessee, or was just passing through. There was definitely a familial relationship between King, the SCLC, Highlander, and even Knoxville for more than a decade," Maxfield-Steele said.

For a decade, Highlander hosted workshops involving prominent civil rights leaders including Stokely Carmichael. The harassment continued: The Knoxville center was both firebombed and picketed by the Ku Klux Klan.

Robert Booker, a former state representative and former director of the Beck Cultural Exchange Center in Knoxville, told Knox News he made a phone call during the Highlander Center's time in Knoxville to the assistant fire chief who had been publicly tying the school to communism.

"He said that you wouldn't believe the communist literature we found at the school. So I called him up and I said, 'Well, you would find more than that if you went down to the Lawson McGhee Library. They were doing everything they could to lambaste Dr. King and tie him to communism," Booker said.

The center moved to its current site in New Market in 1972 after urban removal demolished much of the Black neighborhoods near downtown Knoxville. The center's work has continued there in the decades since, tackling issues from the environmental consequences of strip mining to the rights of immigrants and refugees.

King's lasting impact on Knoxvillians

Knoxville, like many other cities in the region, was a hub for organizing around labor and racial justice issues.

Many in Knoxville recall King’s visits to the city and say his presence made a difference then and now.

East Tennessee Historical Society President and historian Warren Dockter remembered King's visit to Knoxville just three years after the Highlander speech. A crowd of more than a thousand Knoxville College students, teachers and community members gathered on the school's lawn.

“I think of his magnanimous nature in his speech at Knoxville College in 1960 called ‘It’s a Great Time to Be Alive.' In his words we can see one of the things which made King so utterly profound and that is despite knowing the sins of his enemies and oppressors, he counseled for clemency and acceptance," Dockter said.

“We’re on the threshold of the most constructive period in history with regard to race relations. I’m convinced that segregation is on its death bed and the only thing uncertain is the day it will be buried,” King said in Knoxville. “The temptation, for those of us who have been trampled on, is to enter the new age with hate and revenge in mind. If we do that, the new order will be nothing more than a duplication of the old."

The striking words expound on the King's Christ-centered convictions and approach to race relations.

“That speech Dr. King gave at Knoxville College was one of the best I ever heard him give. Unfortunately, the local press paid no attention to him coming here. It was as if he was here and gone," Booker said.

Local news publications at the time, including the Knoxville News Sentinel, provided little coverage of King’s visits, but his growth from a young aspiring preacher to a world-renowned leader birthed a movement, eventually forcing news organizations to take notice, echoing his cries for an integrated society.

By 1960, several Knoxville restaurants integrated their lunch counters after sit-ins, and the University of Tennessee at Knoxville accepted its first Black students the next year.

The wave rolled on throughout the decade. By the end of the summer of 1963, under pressure from Knoxville demonstrators including Booker, the Tennessee Theatre, restaurants and hotels agreed to admit Black customers.

King’s legacy a reminder of radical love

Highlander Center’s first Black woman director, Ashlee Woodard Henderson, told Knox News that King inspired a generation of activists in Knoxville and throughout Appalachia. King, she said, was a "radical' who was nothing more than love personified.

“There’s an intent around this word 'radical' that we saw used to try and bring the Highlander Center down. It made people think there was no way that we could make people’s lives better by being good to each other and making sure everyone has what they need. Everybody gets to be human, with value, and dignity, and live in safe, healthy and equitable communities," Henderson said.

"That's not a big bad scary thing. We need to remember that was the legacy of Dr. King, that’s what radical means, and to acknowledge that opens us up in Knoxville, the state, throughout Appalachia and in this country to actually getting to live good lives. That is why King had this notion of love, nonviolence, and beloved community.”

Henderson cites three main ills King was fighting to end: militarism, racism and white supremacy.

“For us to value Dr. King, we have to continue to challenge those things until they aren't harming people any more," she said.

Many of today’s generation of activists and those fighting for change would be King’s contemporaries if he were still alive, Henderson said.

“Dr. King was young, his political beliefs and spiritual values were not popular with a vast majority of folks who thought he was asking for too much too quickly. I think we need to look at how right he was about what this world should be.”

Angela Dennis is the Knox News social justice, race and equity reporter. You can reach her by email at angela.dennis@knoxnews.com or by phone at 865-407-9712. Follow her on Twitter @AngeladWrites; Instagram @angeladenniswrites; and Facebook at Angela Dennis Journalist.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: Martin Luther King Jr.'s 1957 Tennessee visit sparked a movement