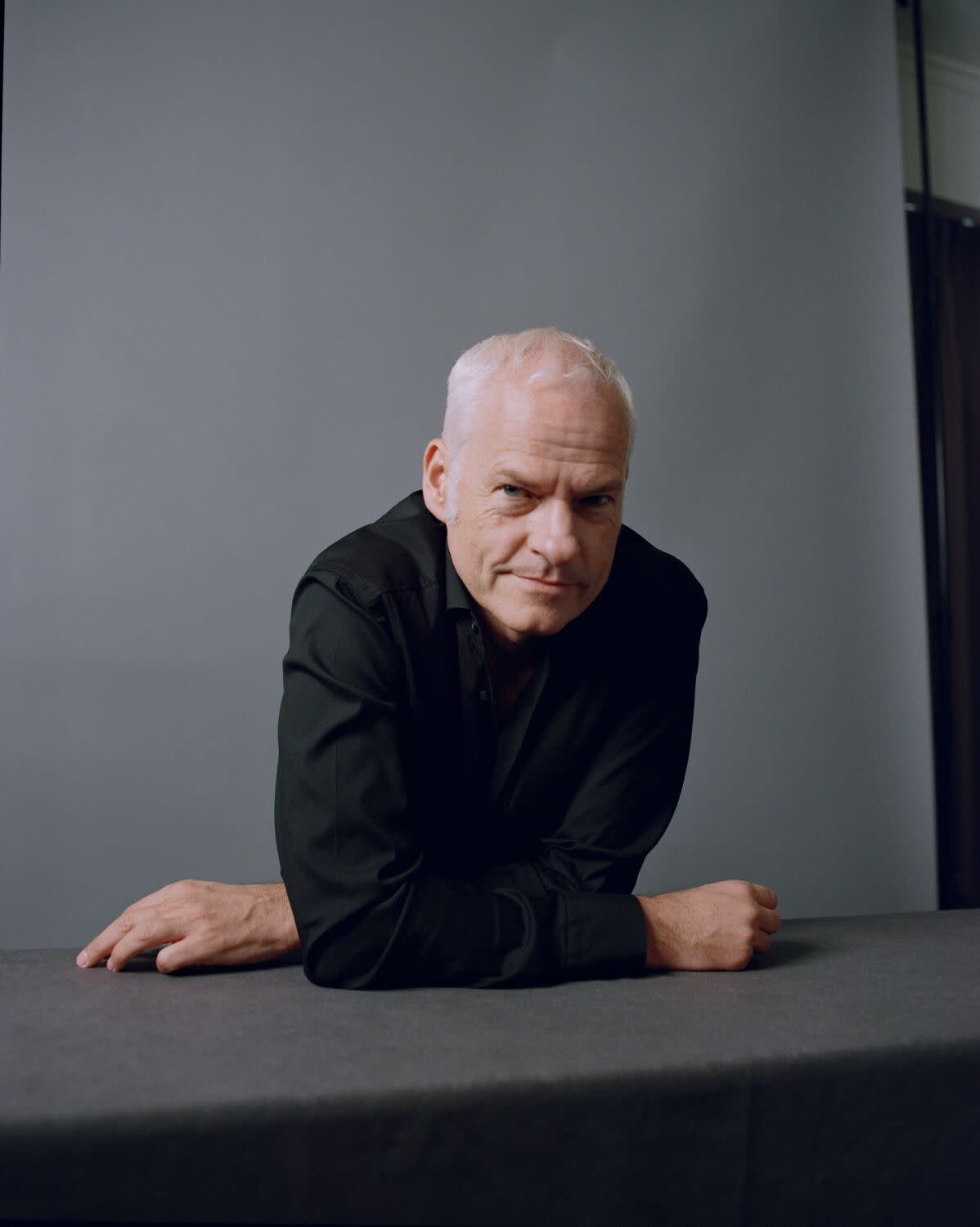

Martin McDonagh loves his stars: 'I don't want anyone else to get their hands on them'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Several years ago, Martin McDonagh started work on a play called “The Banshees of Inisheer.” He didn’t care much for it, but he liked the title, with its echoes of his plays “The Cripple of Inishmaan” and “The Lieutenant of Inishmore.” A few years later, he began writing a screenplay that included two friends who had come to an impasse in their relationship. “The first five minutes were the same as our movie, but then it went to a very plotty place and it wasn't focused on that falling out,” McDonagh said in a recent video call from his London home. “So I kind of scrapped it.”

It didn’t stay scrapped. About three years ago, McDonagh picked it up again and liked what he saw in those first five minutes: an intensive look at a friendship run aground. He realized that was the focus. And that’s how “The Banshees of Inisherin,” a pitch-black comedy that garnered nine Oscar nominations, came into its howling, absurdist existence. A gorgeous movie fueled by pain (emotional and physical) and quiet volatility, “Banshees” is the least “plotty” film McDonagh has made. The story is minimalist. It often feels like a violent Beckett play, with a sense of comic timing to match its despair.

The first sign that McDonagh might have something special came at the film’s world premiere at the Venice Film Festival in September, where the audience hung on every word and erupted in a long standing ovation at the film’s conclusion. Venice audiences are known for such ovations, but this one went on and on and on. The “Banshees” contingent in attendance, including McDonagh and stars Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson, stood and waved from the balcony, smiling sheepishly. “It’s slightly embarrassing,” McDonagh says. “You're appreciative of it, but then we're not the type who blow our own trumpet.”

McDonagh won the festival’s screenplay award, and Farrell was named best actor. Both are now nominated for Oscars — McDonagh for directing, writing and producing — along with Gleeson and Barry Keoghan (both for supporting actor) and Kerry Condon (supporting actress).

Set on the fictional Irish island of the title, “Banshees” is the story of a breakup, though not the kind we’re used to seeing onscreen. As the movie begins, Pádraic (Farrell) stops at the cottage of his buddy Colm (Gleeson) to go get a pint at the pub. But Colm doesn’t want to get a pint. In fact, Colm doesn’t want to be Pádraic’s buddy anymore. He finds Pádraic dull and, in his advancing years, he figures he has no more time for dullness. But this isn’t a modern city, where the aggrieved parties can retreat to the next distraction. It’s a tiny island, in the year 1923. There’s nowhere to hide.

From such humble loggerheads is the “Banshees” tragedy built, mirrored by an Irish civil war on the mainland, heard but never seen. For McDonagh, the central idea was simple. “Sometimes, a platonic breakup can be even worse than a romantic one,” he says. “In a romantic breakup you get it, you've been through it before, you can understand the issues. I think there's something more deeply personal about a platonic friend not wanting to have anything to do with you, because that is basically about you and your personality. It's not like there's this vague romantic thing, which you didn't tick all the boxes for.”

This isn’t McDonagh’s first dance with Farrell and Gleason. In his 2008 film “In Bruges,” also Oscar-nominated for original screenplay, the pair play hit men dispatched by their boss (Ralph Fiennes) to the fairy-tale-like Belgian city of the title. Their chemistry is obvious. Farrell is the wounded, almost childlike naïf who doesn’t appreciate his surroundings. Gleeson is the older pro who’d like to take a load off. There is tragedy here too, along with natural beauty and McDonagh’s humor that makes one choke on the laughter.

McDonagh knows what he has in his unassuming stars. “They're not afraid to show the fragility and the pigheadedness of men,” he says. “They love each other, and it's crazy that no one else tried to get them together in the 14 years since ‘In Bruges.’ One wonders if that's going to change, but I kind of feel a little proprietorial about that relationship. I don't want anyone else to get their hands on them.”

The island of Inisherin is actually two islands: Inishmore, off the coast of Galway, is where Pádraic’s home is located, as well as many of the roads and fields featured in the film. Achill, which sits off County Mayo, is where the pub and port are set. Born in London to Irish parents, McDonagh was thrilled with the locations, especially since his parents now live within hailing distance of the film’s Inishmore set.

“It was a complete joy,” he says. “On weekends, I could go back and see them. The cast and crew felt like a proper family trying to do a good one, literally on an island together. So there weren’t any people going away for the weekend. At nighttime you'd see each other in the pub, or walking around the island on weekends. So we really felt like we were in it together, doing a good Irish movie together.”

“The Banshees of Inisherin” is driven by a fruitful tension. Its core conflict gets quite nasty, almost like a biblical feud. But it all unfolds in idyllic surroundings.

“I wanted to have this horrible, ugly little war between these two guys happen in the most beautiful place,” McDonagh says. “That meant finding the perfect islands but also shooting at a time of the year that would allow us the most daylight, the most magic-hour time, the most sunsets, all of that. We wanted to show the difference between the horror of the story and the beauty of the island and just to make it the most cinematic thing possible.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.