Mass. bill would establish 'right to repair' for cellphones, computers

BOSTON — When David Webb first started fixing computers as a teenager, he could access a laptop battery using a quarter to open the compartment.

Now Webb, owner of Hami!ton Computer Repairs on Park Avenue in Worcester, finds that the battery compartments are glued or soldered shut, replacement parts too expensive or impossible to acquire and the how-to information is a closely guarded secret controlled by the manufacturer.

“Companies are using fewer screws and more glue. It’s an anti-repair design,” Webb said during a sit-down with lawmakers Thursday at the Statehouse.

Webb's shop employs two full-time technicians and three interns and offers a flat rate and a pre-repair estimate.

“These devices are designed to be discarded,” he said.

Massachusetts lawmakers have filed a right-to-repair bill targeting electronic devices, particularly computers and cellphones. The bill, sponsored by Sen. Michael Brady, D-Brockton, and Rep. Adrian Madaro, D-East Boston, would ensure the ability to repair a device so that the investment in it is not lost when that device malfunctions.

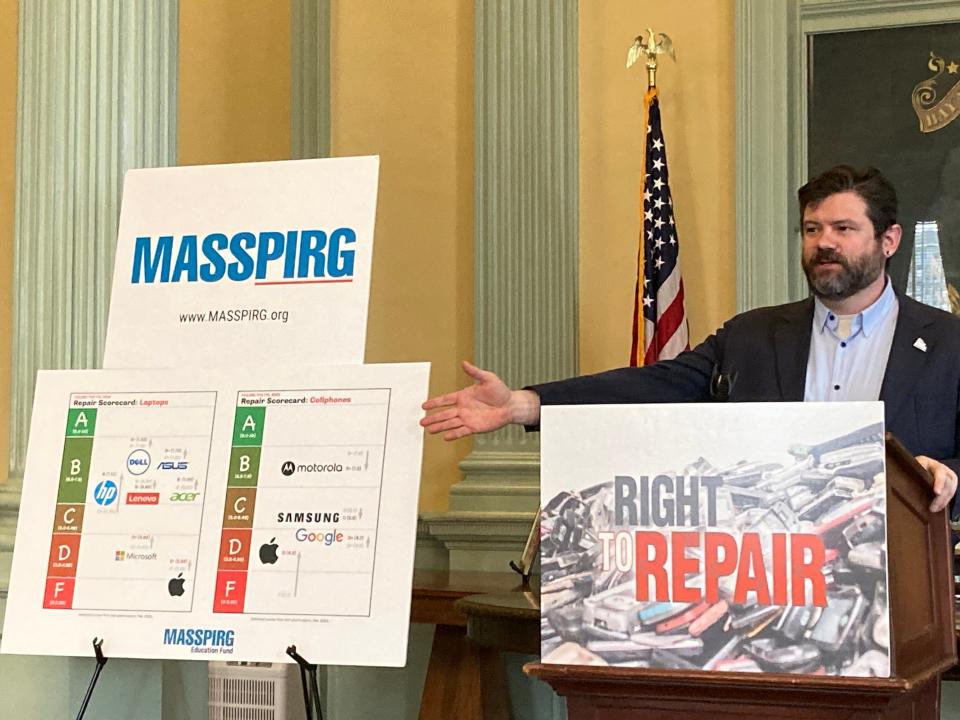

“No one walks into (an electronics store) and asks for a device that’s unfixable,” said Nathan Proctor, of U.S. PIRG (Public Interest Research Group). Proctor coordinates the national right-to-repair movement and attended a briefing on the bill Thursday in support of local efforts.

New York was the first state to pass the measure. If approved, Massachusetts could be the second.

Bill would ensure repairs, parts, how-to info all available

The bill would make information about products available to technicians as well as hold manufacturers accountable for the performance of their products.

European consumer groups, Proctor said, have already demanded manufacturers release the technical information needed to fix devices. These groups have issued report cards, grading both the devices and their makers on the ease of repair.

Given a choice between comparable devices where one is repairable and the other is not, consumers, Proctor believes, would opt for the one that can be fixed.

“There have been some improvements in the last year,” Proctor said, noting that European consumers have a leg up on Americans on electronics repairs. “More than 53% of Americans have presented items to be fixed and were told that repair would be impossible.”

Compounding the lack of public “how-to” information is the lack of replacement parts, their high cost and the introduction of new models that push older ones out of production and out of manufacturer support systems.

Apple, Webb said, restricts who can repair its products, authorizes few repair shops and demands that only Apple products be used. Even authorized vendors can lack access to the tools and parts needed for repairs. And manufacturers lean more toward replacing a device rather than repairing it, pushing the replacement of a motherboard at a cost of $650 rather than replacing the $30 part that malfunctioned.

Once one manufacturer limited access to information, parts and tools, others followed suit, said Webb. Now, consumers are told, "Just buy a new one," Webb said.

The bill would save consumers money as well as benefit the local economy, Brady said.

“People don’t have the money to throw away and get a new device,” Brady said. Most would opt to repair over replace if given the choice.

Almost half-million phones discarded daily in US

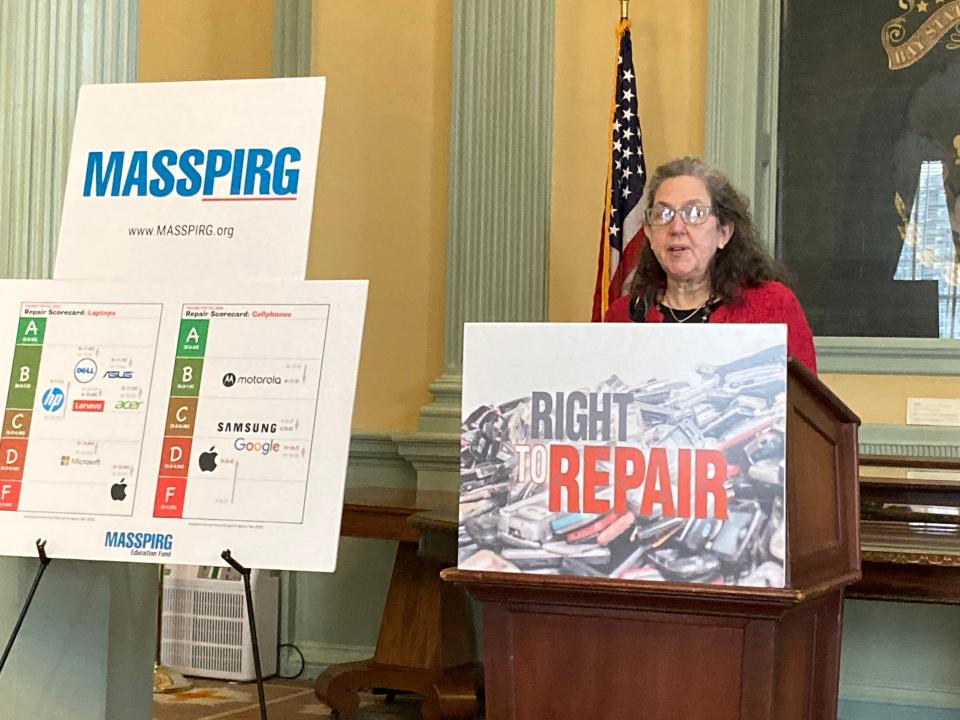

Americans discard more than 416,000 cellphones every day, with most of those ending up in landfills, according to Janet Domenitz, executive director of MASSPIRG.

“Electronic waste is the most poisonous, toxic waste and we are tossing it into landfills,” Domenitz said.

The bill seeks to protect the environment from the electronic toxins, the lithium from the batteries and the heavy metals in the device.

“People need to be able to repair these devices, keep them,” Domenitz said. “It’s also a question of accountability. Corporations are selling these items. They are not inexpensive and they are keeping us from access to repairs.”

The demand to repair devices increased throughout the pandemic as more and more people worked remotely and used their own devices to access jobs.

Own or lease? In Mass., it's death till you part

Currently, they agree, consumers don’t really own cellphones or computers; they just lease them until the device dies. It could be a problem with a component or a malfunctioning battery.

Most batteries have an active life of four to 10 years. But even then, not all the power cells in a battery die simultaneously. If one cell dies, five others could still be functional.

Webb skirts the issue of availability of parts by collecting and storing broken devices he can later cannibalize as needed.

And as for batteries, he is planning to build a power wall for a yurt he owns in another state with all the dead batteries that come into his shop.

This article originally appeared on Telegram & Gazette: Right to repair cellphones and computers may become law in Mass.