Year after mass shooting, Highland Park asks: What does freedom mean this Fourth of July?

HIGHLAND PARK, Ill. − Nancy Rotering once relished the joy of bringing her children to her hometown Independence Day parade − the same one she walked in as a child.

But that joy was shattered last year, when Rotering and thousands of others at Highland Park's Fourth of July celebration fled in terror after a gunman armed with an AR-15-style rifle opened fire from a rooftop.

Tuesday, Rotering plans to lead her community in a solemn walk to reclaim the beloved parade route forever marred by the shooting that killed seven people and injured nearly 50 others. There will be no floats and no performers.

The city is also expected to hold a remembrance ceremony in the morning, a community picnic in the afternoon and a concert and drone show in the evening, instead of fireworks. People are still sensitive to the sound of loud pops.

"We had and suffered through a uniquely American experience on this uniquely American holiday, so to be working to celebrate freedom at a time when our nation is still allowing this kind of threat to be so pervasive is a difficult balance to strike," said Rotering, the 61-year-old mayor of the still-grieving community.

One year since the mass killing in this Chicago suburb, Highland Park residents and survivors are at different stages of grappling with the traumatic event and coming to terms with the new meaning of July 4th.

"There are not only seven families grieving. There are dozens of people who are still struggling to recover from devastating and complex injuries. There are people who are bearing emotional scars and trauma from seeing things they never should have seen," Rotering said.

A complicated year in Highland Park

Thousands of people were at the parade. Many fled and sheltered for hours as the gunman traveled to Wisconsin and back before being apprehended that evening. Everyone affected by the shooting has had a different experience, Rotering said.

The victims, ranging in age from 35 to 88, were loving parents and grandparents, including the mother and father of an orphaned toddler. Some survivors are no longer comfortable at large gatherings. Others moved away. Many, including Rotering, have experienced symptoms of PTSD.

For the Roberts family, the past year has meant countless hours in the hospital and in therapy, relocating to a wheelchair-accessible home and a delayed start to third grade for 8-year-old Cooper, who was paralyzed from the waist down.

"He can’t be on the soccer team, bounce on the couch or wrestle with his brother. When he should be going to sports practice, he is attending physical therapy," Cooper's mother, Keely Roberts, wrote in a recent online post. "Yet, amidst the sadness, we are astonished by his resilience and hope as Cooper has started participating in Adaptive Swim Meets and is learning wheelchair tennis. We are figuring out new ways to participate in the world."

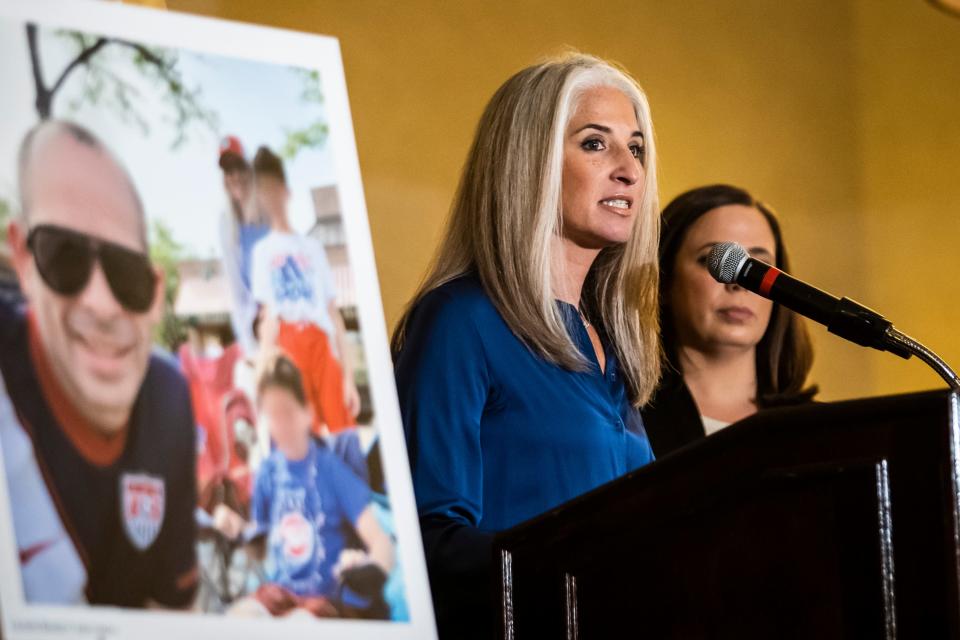

Survivor Ashbey Beasley, 47, said her 7-year-old son was diagnosed with PTSD and will have an individualized education plan at school this year. Her husband, who was not at the parade when the shooting happened, has struggled with guilt. They're acutely attuned to when other mass shootings happen in the United States.

Beasley and her son were visiting Nashville in March when a shooter armed with two "assault-style" rifles killed three children and three adults at a small Christian elementary school. Beasley was preparing to have lunch with a fellow gun violence survivor − a woman who lost her son in the city's 2018 Waffle House shooting − when gunfire broke out.

"Only in America can this happen," said Beasley, who spoke to reporters that day.

About a week later, Beasley's son locked down at school after nearby Highland Park High School received a tip of a student with a gun. No shots were fired, and five students were taken into custody, city officials said. The incident set off panic in the area and spurred heated debates on school safety, Beasley said.

Are shootings really 'out of control'? US gun violence statistics to know this July 4th

Residents have also been divided over where to place a memorial to the shooting victims.

"Some people want a memorial in a very public place where everybody sees it. Other people aren't as comfortable seeing it all the time," said Rabbi Adam Chalom, 47, of the Kol Hadash Humanistic Congregation in neighboring Deerfield.

Chalom and his wife were at the parade, walking behind the Maxwell Street Klezmer Band, when the shots were fired. Last month, his wife was at a restaurant when somebody popped a balloon − she dove under the table, he said.

The Rev. Quincy Worthington, 42, of Highland Park Presbyterian Church, said he often finds himself planning exit strategies. It's easy to give in to apathy when it comes to issues like gun violence, he said. Instead, his congregation has been focused on building community and reaching out to young people who may be isolated or struggling.

"We've been talking a lot about how it's not the big, flashy things that get the job done, but it's several people doing seemingly small acts of kindness every day," said Worthington, who is expected to speak at the remembrance ceremony.

Alan Freeman, 52, said Highland Park doesn't feel like the same community his family moved to eight years ago. He's looking forward to retiring and moving out. He thinks America is too polarized to be able to address gun violence.

"I'm much more interested in just whatever we have to do for ourselves, for my family, for our town, because nobody's coming to our rescue," he said.

Natalie Lorentz, 35, said she and her husband regularly think about the shooting. She flung herself onto her three children that day as the couple to her right were fatally shot. For her, the trauma frequently manifests as anxiety.

On the other hand, Lorentz said survivor's guilt has forced her family to appreciate being alive. She was pregnant the day of the shooting and gave birth five months ago to twin boys − her fourth and fifth sons. When the babies were just 6 weeks old, the family went to California for vacation.

"We have to live life to the fullest," she said.

'We will not back down': Survivors turn to activism

Many survivors have looked to activism as a form of therapy. Like many before them, they've become close friends with survivors of other mass shootings.

Lorentz and her husband flew to Washington, D.C., 10 days after the shooting and have since made other trips to meet with lawmakers and participate in marches and rallies.

"I do feel like it's become more top-of-mind for people," Lorentz said. "At least I want to be hopeful."

Weeks after the shooting, Rotering testified at a Senate hearing on gun violence and called on lawmakers to reinstate the federal "assault weapons" ban that expired in 2004. She's long been an advocate for gun control: Highland Park passed a municipal ban in the wake of the 2012 mass shooting in Newtown, Connecticut.

That ban didn't stop the gunman from purchasing weapons from locations in the Chicagoland area. Using a Smith & Wesson M&P 15 semi-automatic rifle, he fired 83 rounds into the crowd in less than a minute, Rotering testified.

An Illinois grand jury indicted the gunman on 21 first-degree murder counts, 48 counts of attempted murder and 48 counts of aggravated battery. The gunman's father also faces seven counts of reckless conduct for helping his son obtain a gun license even though he had threatened violence. Attorneys have not set trial dates.

Survivors and victims' families have taken legal action, too: Plaintiffs are suing the gun manufacturer, the gunman and his father, the gun store where the gunman purchased the weapon and an online gun distributor.

In late July, the U.S. House passed a bill that would make it illegal for anyone to import, sell, manufacture, transfer or possess certain semi-automatic weapons. The bill has since stalled in Congress. But a number of states have pursued the issue.

Earlier this year, the governor of Illinois signed a law that bans dozens of high-powered semi-automatic weapons and high-capacity magazines, among other reforms, making Illinois the ninth state with a ban on so-called "assault-style weapons."

Beasley testified on behalf of the legislation. She also recently created a website that encourages Americans to schedule hometown meetings with federal representatives, in the hopes of gaining momentum for a federal ban.

Abby Kisicki, 24, has been hosting digital lobbying sessions every Monday evening for the past eight months, making calls with people across the country to pressure lawmakers to pass gun safety legislation.

As she fled the parade with her parents that day, a bullet flew over her father’s head and shattered a window. A month later, she became involved with Newtown Action Alliance, a nonprofit formed after the Sandy Hook shooting.

Kisicki said that, as a member of Gen Z, she's grown up accustomed to school active shooter drills and news of mass killings. She said she was unsurprised by the shooting that day.

Thursday, she and Beasley attended a rally in support of the new Illinois gun safety law. The legislation promptly met challenges from gun rights groups, and a federal appeals court heard arguments in a consolidated case last week. Legal experts say the outcome of the proceedings could have potential ramifications for other states.

"We will not back down," Beasley said.

In Highland Park, a July 4 remembrance ceremony instead of a parade

Thousands of people have signed up for the remembrance ceremony and walk, Rotering said. Since some are staying home or leaving town, the city is hosting a livestream of the events, too.

"We will be, on the Fourth, a city in mourning and a city of resilience," Rotering said.

Chalom said his family signed up for the walk. He and his 15-year-old son had a positive experience marching in a suburban Pride parade last month, and they're ready to be in a big crowd again.

Lorentz said her family plans to have friends over for a backyard barbecue. Her older kids, 6 and 4, don't want to go to a parade. But she's been surprised they've expressed interested in seeing fireworks. The family may attend the show in a nearby town.

Freeman said it's been odd having to register in advance for gated events.

"You're not really celebrating independence at that point, right? It's a really odd juxtaposition," he said.

Hours after the shooting happened, Kisicki vowed she’d be back for the parade the following year. A year later, her feelings have changed.

She thinks about the shooting constantly and tries to honor the victims through action. Participating in the city’s events wouldn't help her mental health or grieving process. So, she'll be in Boston this week visiting extended family.

As soon as she's back, she'll be hosting those Monday night phone-banking sessions. This Fourth of July, she's encouraging Americans to get involved in their own communities.

"Hope is not naïve," she said. "Things will indeed never change if we don't take action."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Highland Park shooting survivors ask: What does July 4 mean this year?