‘Massive, systemic and institutional.’ How Lexington intentionally created a segregated city. | Opinion

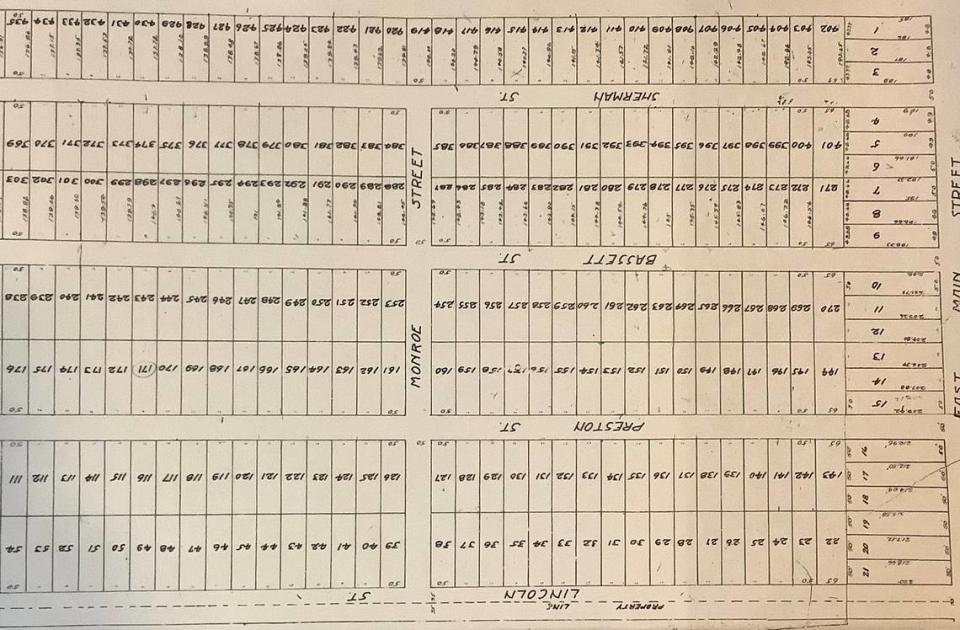

In 1909, the Wickliffe Land Company created one of Lexington’s first subdivisions. The streets of Lincoln, Preston, Bassett and Sherman were lined with brick and wood bungalows standing in small gardens, built for working class families as Lexington began to grow into the new century. Now known more generally as Kenwick, the area is considered one of Lexington’s most charming and sought after places to live.

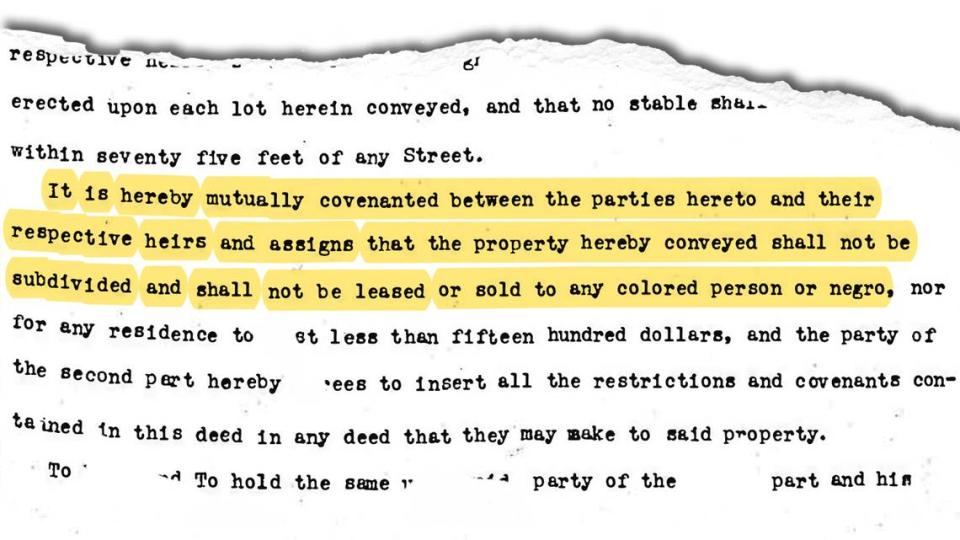

But in the fine print of the house deeds was a darker reminder of the century before: “It is hereby mutually covenanted between the parties hereto and their respective heirs and assigns that the property hereby conveyed shall not be subdivided and shall not be leased or sold to any colored person or negro.”

Known as a racially restricted covenant, these deeds were commonplace across early Lexington and the rest of the country, part of a system of laws in the wake of Reconstruction to segregate the races. No area of “de jure” segregation was more prevalent than housing. It included racial restricted housing deeds, also called covenants, and redlining, whereby federal loan agencies and local banks would deem certain areas of town unworthy of loans.

A few decades later, federal urban renewal policies would hand down grants to “improve” neighborhoods, which resulted in destroying broad swathes of Black neighborhoods. The results were both immediate and far-reaching, cutting multitudes of Black citizens out of home ownership, which then created a wealth gap that exists to this day.

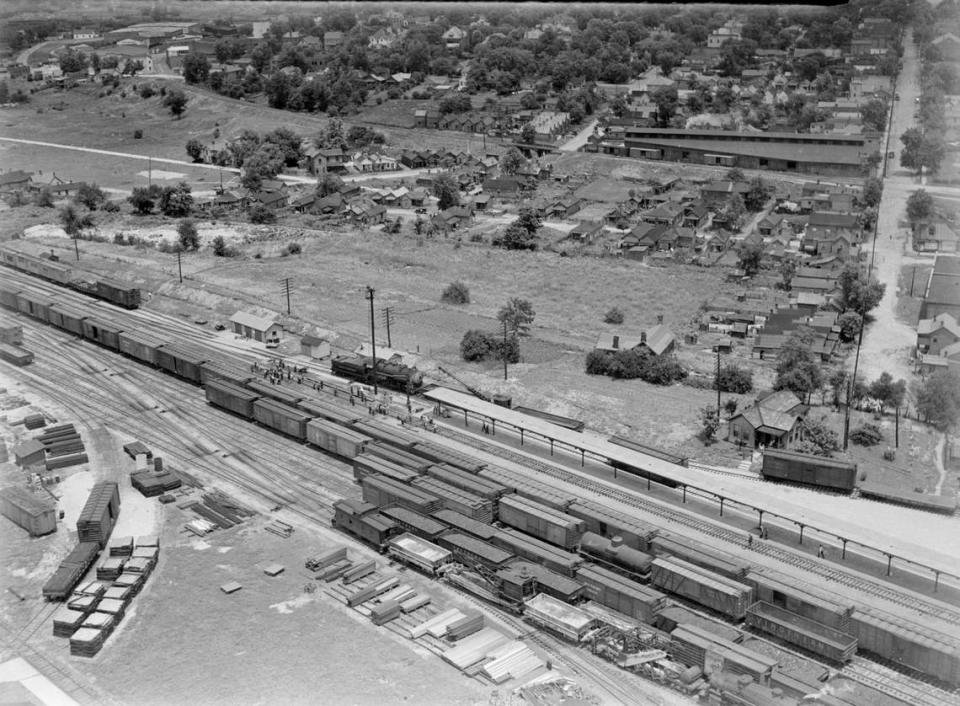

“It was about containment and erasure,” said Rich Schein, a University of Kentucky geography professor who has researched the topic. In 1870, Schein said, Lexington still looked like its Civil War days, where the enslaved lived “cheek by jowl” with white people. But soon enough, Black people were either shunted to the corridors of Georgetown and Newton or the East End and rural Black hamlets while numerous Black neighborhoods, like Adamstown — torn down to build Memorial Coliseum — were swept away in the name of progress.

None of this is new information; historians and journalists have chronicled these problems, including the Herald-Leader, which wrote series on the topics in the 1980s and 1990s. But here in Lexington, a series of serendipitous events, including a Lexington Public Library exhibit on Lexington’s redlining, a community read-along of one of the most important books about redlining and a detailed new website about Lexington’s history of housing segregation will put unprecedented attention on these topics for the first time.

Facts, not guilt

“Segregated Lexington” was created by two senior citizens who were in despair over the state of race relations in the spring of 2020, as racial justice protests over George Floyd and Breonna Taylor rocked Lexington and the rest of the country. An article called “Centering Blackness: The Path to Economic Liberation for All” led Barbara Sutherland and Rona Roberts, who are both white, to start pulling together information about why Lexington’s own race issues were so acute. The easiest place to start was housing because it focused on irrefutable documents rather than feelings about race and racism.

“This is not about making white people feel guilty,” said Sutherland, a retired city employee and librarian. “But it is about getting white people to understand what has led to the situation and to recognize how unfair the situation has been and how the results of that unfairness continue to this day. A major result of that kind of intentional, persistent segregation was that African Americans had much much less opportunity to build wealth through home ownership, and I think white people need to know about that.

“I grew up thinking up that I and my family were making it on our own steam, and I had no idea about all that had been put in place to help us get ahead that had not been given to others.”

Segregated Lexington is divided into sections that chronicle each of the ways Lexington legally segregated Black residents, from racially restricted convenants to redlining to zoning and realtor steering. Like every city in the South, Lexington’s fortunes were built with enslaved Black labor, people bought and sold at one of the largest slave markets in the country. After the Civil War, the city was no slouch at continuing to oppress its Black residents, who numbered nearly half the population in the post-war years.

“I knew things like racial covenants existed, but I was still shocked at the number of them, and how they would cover entire subdivisions,” Sutherland said. Racial covenants were ruled unenforceable in 1948, but she estimates that nearly every neighborhood built before then contained them.

“We didn’t look at Chevy Chase, for example, because we assumed there would be restrictive covenants there. What we were looking for was where ordinary working people could have afforded to live and that meant African Americans as well,” she said. That means once-working class neighborhoods like Kenwick, Forest Park, Suburban Court and Goodrich were also off limits to Black residents.

Redlining

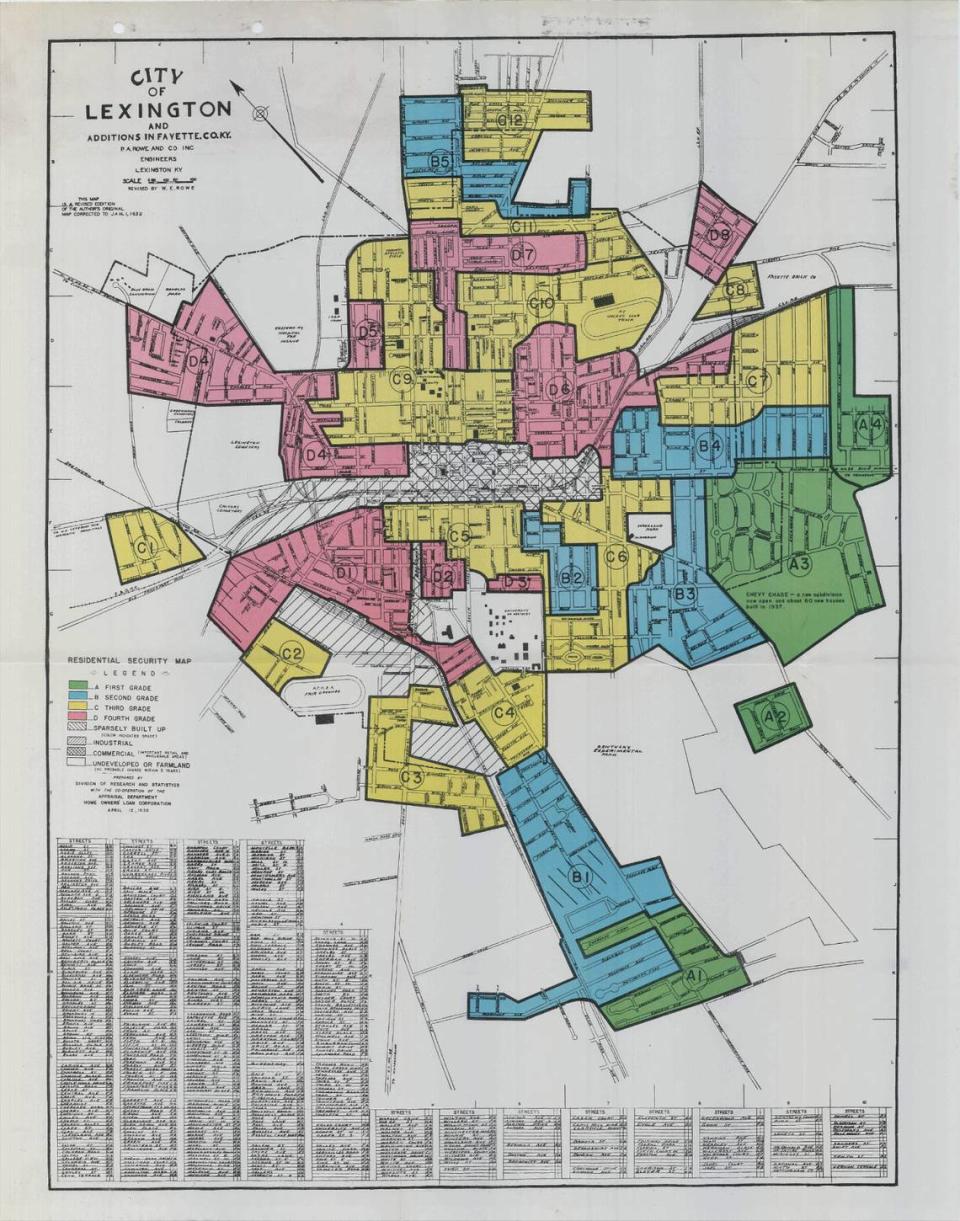

Segregated Lexington cites an influential short film called Segregated by Design, a succinct explanation of redlining. This was basically segregation under the aegis of two federal agencies, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), which were created in the 1930s as part of the New Deal to help the country heal from the Great Depression.

The FHA provided mortgages and the HOLC refinanced struggling homeowners. But in both cases, they were guided by local officials and by maps about where safe investments could be made. Black neighborhoods were outlined in red, with accompanying language: “If a neighborhood is to retain stability, it is necessary that properties continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes,” according to the 1938 FHA underwriting manual.

The FHA redlining maps have largely disappeared, but the 1938 HOLC map shows a pattern of segregation that still exists today. In green, or “best,” is Chevy Chase, “a new neighborhood of 60 houses built in 1937.” Blue is “Still Desirable,” and includes Ashland and South Limestone. But the yellow “Definitely Declining,” and red “Hazardous” include much of the northside, especially the East End, where disinvestment continued for decades. Much of High Street was yellow, but a lot of housing was torn down in the 1960s to make way for urban renewal. It’s uncanny how much the map of 1938 foreshadows the communities that still have the highest and lowest housing values today.

The website notes that federal loans pushed much of the post World War II housing boom. The authors say more research is needed on exactly how many, if any, federal loans were made to Black Lexingtonians, but nationally, the number was about 2%. More research is also needed on what local banks did or did not do during this time to aid Black homeowners.

Urban renewal, realtor steering

Eventually, policies like redlining were abandoned or made illegal. But the 1960s gave way to a new federal policy that sent huge hunks of money to local governments ostensibly to clean up poor neighborhoods, but in fact, erased many of them.

Then there was a de facto segregation caused by practices like racial steering, in which realtors would steer clients to certain houses based on race. This had the further effect of creating more school segregation. Anyone who bucked the trend faces recriminations, according to Sutherland and Roberts.

In 1965, one of UK’s earliest Black professors, Joseph Scott bought a house in Cardinal Valley, which was then a new white neighborhood. Realtor Ben Story, who was white, sold the house to the Scotts, but was harassed by other realtors: “at a professional realtors’ event not long after the sale to Dr. Scott, there were publicly stated calls, clearly directed at Mr. Story, for realtors not to sell homes in White neighborhoods to Blacks.”

Kristen LaRue Bond is a Lexington native and local realtor with Lifestyle Real Estate. She’s also the president of the Central Kentucky chapter of the National Association of Real Estate Brokers, a Black organization formed because Black realtors used to be prohibited from joining white realtor groups. She’s watched Sutherland and Roberts present Segregated Lexington several times, and while its content was all too familiar to her, she appreciated the work.

“I think it’s really impactful,” she said. “It needs to be seen by every member of every planning and zoning committee or anyone invested in housing in the Lexington area.”

Bond knows how important home ownership is to get ahead because her family experienced it. Her grandparents started in public housing in Charlotte Court, then were able to build a small house in the St. Martin’s neighborhood. Her father, Gregory LaRue remembers when they moved onto Oak Lawn Park near Gainesway in 1971, which was predominantly white. The LaRues didn’t have any problems there, but friends of theirs who moved at the same time to Blairmore Court near Henry Clay High School, had their house spray-painted with the n-word.

“We grew up knowing that it’s very important that you are able to own a home,” LaRue said.

Bond believes that steering still goes on, albeit in very subtle ways.

“It’s not as intentional as people think, but if your form of advice is stigmatizing a community, then you need to know that has consequences down the road,” she said. As a member of the diversity committee for Bluegrass Realtors, she’s working with president Justin Landon to turn the Segregated Lexington website into a documentary that can be used as continuing education for realtors.

Landon said the website provided “an opportunity for us to engage more directly of how we raise awareness around the topic. We have to acknowledge it’s a massive, systemic, and institutional problem. As long as it took to cement, it will take to undo.”

As to that, Sutherland and Roberts will leave the solutions to these problems up to us. They want people to understand the problem and how we got here with a series of indisputable facts. The women are doing Zoom presentations and in person workshops every few weeks on the site.

“All the segregating forces made something that can’t be quickly undone so white people are still benefiting from a lot of unfairness and Black people are still being harmed by these policies,” Roberts said.

Learn about Lexington’s history of segregation, redlining at these community events