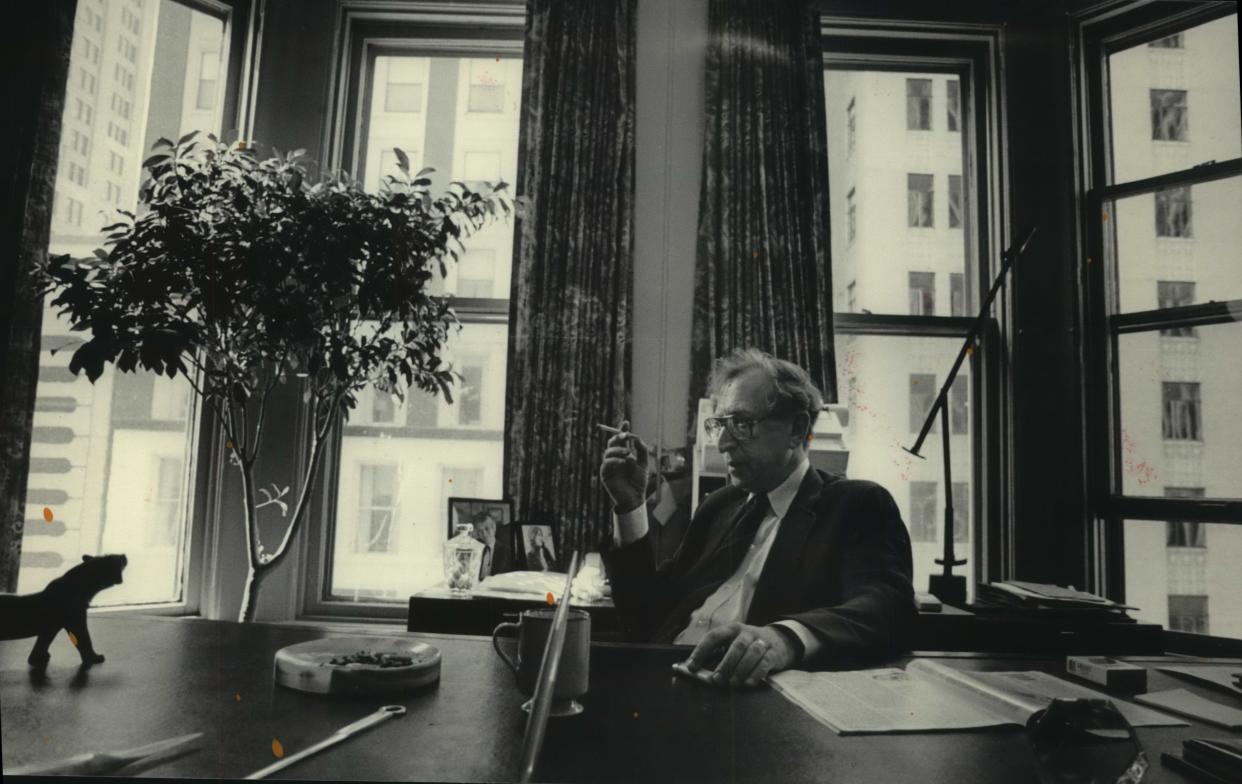

"Master of the technical": James Shellow was the prominent Milwaukee lawyer who defended civil rights leaders, mob bosses

James M. Shellow, one of Milwaukee's most reputed criminal defense attorneys known for representing civil rights leaders as well as organized crime bosses over his more than 50-year career and who inspired an array of defense attorneys in the city and beyond, has died.

He died on Oct. 29 at his Milwaukee home, from an illness with COVID-19, his daughter Jill Shellow said. He was 95.

Shellow was a local legend who came to the legal profession later in life, but quickly rose in prominence as a formidable defense attorney in Milwaukee, one who would push boundaries and challenge others to think beyond the conventional and the status quo.

“I saw him as a man that was the cutting edge on arguing constitutional law, on challenging the statutes that had been long accepted,” said E. Michael McCann, former Milwaukee County district attorney, whose office of prosecutors was often opposite Shellow in the courtroom. “He was a master of the technical.”

One of Shellow’s early cases prompted the Wisconsin Supreme Court – in a “precedent shattering decision” – to modernize the test used by courts to determine a defendant’s sanity, the New York Times reported in 1966.

Before, a defendant in Wisconsin was only considered insane if they did not know the difference between right and wrong. But Shellow argued in favor of a new test, under which a person may be considered insane if he is unable to control his conduct because of a mental disease.

He was also well-known for his skills cross-examining witnesses, an ability that made him a sought-after criminal defense attorney not only in Wisconsin, but nationally, said longtime friend and colleague Dean Strang.

Shellow was especially skilled at questioning forensic analysts in drug trials, a subject he even wrote a book about, “Cross-Examination of the Analyst in Drug Prosecutions.”

He sought to undermine the testimony of drug analysts, by sowing doubt in their qualifications as “experts” and getting them to admit their lack of understanding of chemistry and other sciences underlying forensic drug analysis, Strang said.

“You find that these people really aren’t experts,” Shellow told the Milwaukee Journal in 1979.

Shellow once compared his style of cross examination to German warplanes and their terror-inducing sirens.

“He had a withering style of cross-examining a witness,” Strang said. “It controlled the witness, and because of his verbal precision, it left the witness almost no room for evasion.”

Other defense attorneys admired him for his “ferocious capacity for work,” at times sleeping only a few hours a day, and for his commitment to his clients, whom he didn’t want locked in “cages,” Strang said.

Prosecutors respected his abilities and did well to "expect challenges that you wouldn't find elsewhere," McCann said.

"Prepare for esoteric detail with Jim," McCann said. "Jim's skill was clearly the law, command of the law."

Despite his success, Shellow made time for other lawyers who sought his help and guidance, Strang said. He became a mentor to many younger lawyers, especially later in life when he held regular, informal meetings with lawyers called the "Shellow school" to discuss legal issues, formulate legal strategies for their cases and build camaraderie.

"One of his favorite questions was 'why?' " Strang said. "Why do they do this? Why is it done this way? Why does everyone think this way? ... He had that brilliance and capacity for curiosity and asking questions."

He inspired dozens, if not hundreds of other lawyers, including those who worked at his firm, young proteges whom he took under his wing, pupils of his training sessions at the National Criminal Defense College, which he helped co-found – and even his two daughters.

'Right in the thick of it'

James Myers Shellow was born on Oct. 31, 1926 in Milwaukee, the older of two sons, to Henry and Sadie Shellow.

The family of four lived in Shorewood. Henry worked as an accountant, and Sadie as a psychologist.

From a young age, James developed a love of reading and literature, in part born of the stories Sadie would read to him and brother Robert before bedtime, Robert Shellow said in an interview. He was also gifted in mathematics and enjoyed working with chemistry sets as a young man, interests that he would later apply to his legal career, his younger brother said.

During a brief stint in the Navy at the tail end of World War II, James trained to be a radar technician, his brother said. Then, he studied at the University of Chicago, where, in 1949, he met Gilda Bloom, a graduate student in psychology.

They were married a year later.

Following graduate school, James took a job working for a military airplane manufacturer, a career that ultimately left him unsatisfied, his brother said. He then went into accounting and worked with his dad, before ultimately enrolling in law school at Marquette University in 1958.

“The law really clicked for him,” Robert said. “It gave him the freedom and the individuality and the stage on which to perform I suppose. He was a performative person, no question about it.”

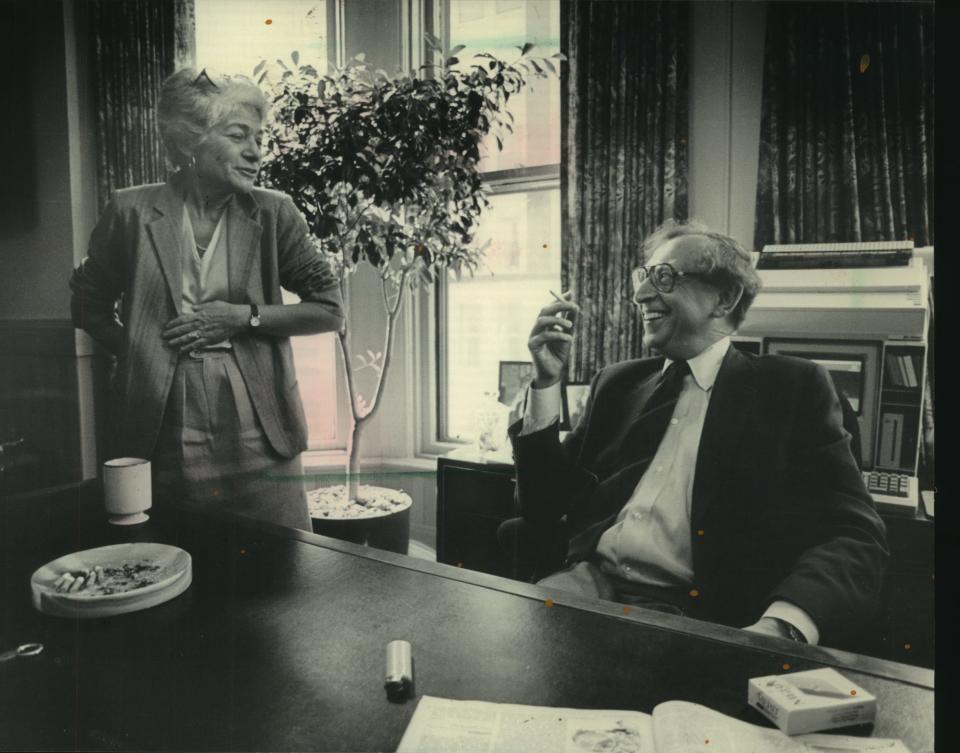

Soon, Gilda took an interest in the books James and his classmates were poring over together at night, and she followed him into law school.

Together, they started a husband-and-wife law practice out of their home on North Lake Drive in Milwaukee, where they also raised their two daughters, Jill and Robin.

The walls of their home were lined with shelves and shelves of law books, a home law library that was the envy of McCann, who lived not far from the Shellows. Jill Shellow remembers as a girl helping her parents by putting small pamphlets, called a "pocket part," into the back of law books, with information on the most current law. She was not allowed on the library ladder except when supervised.

"Dinner-time conversation was about cases and issues and strategies for as long as I can remember," Jill said.

Both she and younger sister Robin went on to become criminal defense lawyers, too, something that Jill regarded as something of a pre-determined, genetic inevitability.

Robin practiced in Milwaukee until she died last year, at times working alongside her dad. She took a particular interest in defending children involved in the criminal justice system.

Jill is an attorney in New York City.

James and Gilda Shellow eventually moved into an office on Mason Street in downtown Milwaukee.

James cut his teeth as a lawyer in the 1960s, a decade marked by civil unrest over the Vietnam War and the struggle for racial justice. It was also that decade when the U.S. Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice Earl Warren, vastly expanded civil rights, including for criminal defendants by guaranteeing the right to free counsel and the right to remain silent, among other protections.

“Jim was right there, right in the thick of it,” McCann said.

Early in his career, Shellow represented Father James Groppi, one of the leaders of Milwaukee's fair housing marches, and Michael Cullen, one of the Milwaukee 14 who stole draft records from the city's selective service office and set them on fire, along with other anti-war protesters and civil rights activists.

As leaders of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, Shellow and attorney Albert Krieger also traveled to South Dakota in the 1970s to organize the legal defense for members of the American Indian Movement charged in the occupation of Wounded Knee.

Jill remembers nights when civil rights leaders would meet at their home to talk or strategize. She and younger sister Robin, already asleep, would be woken up and allowed to sit and listen to the meeting, before being ushered back to bed.

Shellow also defended clients accused of more ignoble crimes, including Milwaukee's one-time organized crime boss, Frank Balistrieri. He also represented people accused of all manner of other crimes, including homicide, drug offenses and other felonies.

Outside of his work in law, Shellow had a taste for expensive and antique cars, brother Robert said.

"I was both a beneficiary and a victim of that interest," said Robert, who had some experience in mechanics and was sometimes called upon to fix a car.

One of Shellow's most beloved cars, Robert said, was a Riley classic that he bought from a seller in England and had driven to his home in France. Robert said the car had nothing but trouble all the way there, and that getting parts for it was a "nightmare."

Even into his later years, as his work was winding down, Shellow was still generous with his advice, some of his mentees said.

Anthony Cotton, the attorney who represented Morgan Geyser in the Slender Man case, said Shellow was "instrumental" in helping him work through the issues in the case. Cotton ultimately succeeded in arguing an insanity defense for Geyser, one of two 12-year-old girls involved in the stabbing of a classmate to please the fictional character Slender Man.

Shellow never quite seemed his age, Cotton said, even though he "smoked like a chimney" for most of his life and was in his 80s by the time Cotton met him through Shellow school.

"The guy never looked tired, and then you'd get home and you'd have emails coming in throughout the night" from him with ideas, he said. "It was like pure, intellectual excitement."

It was that work ethic that will live on in the people he most influenced.

"The best thing I can do to keep his memory alive is to represent people who are most hated in our society," said Jill. "The best I can do to carry on his legacy is to keep working."

James Shellow is survived by his brother, Robert, his daughter Jill and one grandson, Aaron Shellow-Lavine. He was preceded in death by his wife, Gilda, and his daughter Robin.

Our subscribers make this reporting possible. Please consider supporting local journalism by subscribing to the Journal Sentinel at jsonline.com/deal.

DOWNLOAD THE APP: Get the latest news, sports and more

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Lawyer James Shellow who defended many from Groppi to Balistrieri died