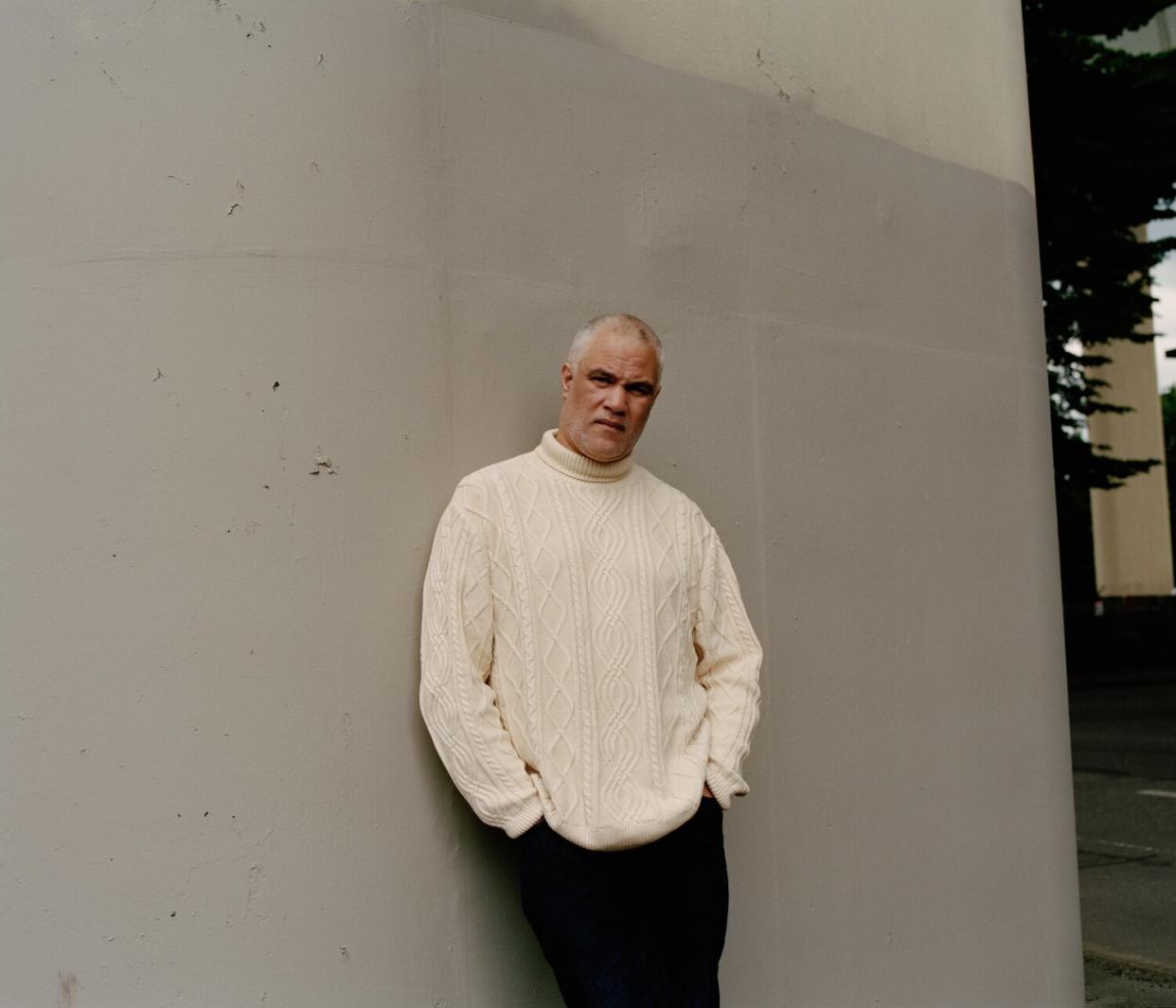

How Mat Johnson's sci-fi space satire captured our COVID-19 crackup — four years ago

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

EUGENE, Ore. — “I think I spend about 28% of my waking day thinking about the reality skills we have,” says author Mat Johnson, “and how we’re not having discussions about two different interpretations of reality. We’re living in completely different realities.”

Overthinking reality and its discontents is an occupational hazard for Johnson, a novelist acclaimed for satires about America’s delusions of self — including a new one about a colony in Jupiter’s orbit, split by divergent interpretations of the collective past, that feels a lot like home.

Well, maybe not Johnson’s current home. He and I are speaking in the proximate reality of a brewpub devoted to Scandinavian braggots on an unseasonably cold day in late May. He has been splitting his time between Portland and Eugene since 2018, when he joined the faculty of the University of Oregon.

“Invisible Things,” out next week, is Johnson’s fifth novel. In the sense of being an intergalactic adventure, it’s a wild departure for the author. But it’s also of a piece with work that’s become instantly recognizable for its blend of satiric wit, heavy underlying themes (including his own mixed-race origins) and a stubborn undercurrent of optimism. You just know a Mat Johnson novel when you read one.

“Pym,” Johnson’s 2010 breakthrough novel about a “failed” Black academic obsessed with a racist Edgar Allan Poe novel, was praised for writing that was “exuberantly comic, sometimes with buddy-film antics, but often with head-shaking incredulity over the insane ways of human beings.”

The author’s 2015 followup, “Loving Day,” was set in Johnson’s native Philadelphia; it was by far his most personal book. His protagonist, Warren Duffy, takes up residence in an inherited house and ends up encountering ghosts, comic books and his teenage daughter, whom he’s never met. He also explores his identity as a “mulatto” — a “racial optical illusion.” As Johnson explained in an interview, the impetus for the novel was that “as an adult, I started growing warm to mixed identity. … But there are still several things I was uncomfortable about. I needed to work through that.”

The novel also set Johnson up for a lot of questions about racial categorization that he didn’t always want to answer. Besides, as Donald Trump marched to the White House, he was broadening his satirical target. The setting of “Invisible Things” is New Roanoke, a space colony that is discovered when a spaceship from Earth, the SS Delaney, is “kidnapped” by the colony's residents. Those residents are descended from 17th century human settlers along with subsequent waves of UFO abductees. Taking off from its wild setup, the novel delivers belly laughs and gut punches in quick succession.

Victor LaValle, a longtime friend and another novelist of color who mixes genres with abandon, admires the sneaky weight of Johnson’s comedy. “Humor/satire is such a great, and classic, way to get at the most painful issues,” he told me via email. “[R]eaders won't realize they've been made to think deeply about something until after they've already started laughing. This is a part of Mat's charm on the page and in real life. To see the absurdity of a moment, or a way of being, and make it clear to others without ever raising his voice.”

Pressed to account for his sense of humor over a pint of Freyja Blonde, Johnson — also the author of four comic books — offers his origin story. “I think the main two things were sheepherding and slavery,” he says. He grew up in Philadelphia, the son of an Irish American father and an African American mother. “I didn't realize my dad was funny until I was in my late teens because he's always muttered at the dinner table, and then I actually started listening to what he was muttering and it was sarcastic, funny things.” His mother’s life, he says, “was triumphant, but it was hard, and humor was an essential part of the way she dealt with it.”

Johnson’s mother and aunt had run away from an abusive father to live in Philadelphia. Later, his aunt married a Jewish doctor. He calls his outlook a “hybrid” of “this Black sense of humor that was very irreverent and essential as far as dealing with” oppression. “And then this Irish sense of humor; it came out of their type of oppression. And then a Jewish sense of humor that came out with that type of oppression.”

“Invisible Things” is dystopian not so much in its sci-fi elements as in its construction of a world in which that kind of hybridity is choked off — and with it any possibility of establishing a collective truth. A rigid class divide splits New Roanoke “between the people who’d been recently ‘collected’ and those who’d been born in the place. … Many within the indigenous population could trace their lineage back centuries — and were notorious for letting others know that whenever possible.” Enormous economic inequality breeds further separation; communication across the divide takes place largely in television sound bites and political slogans.

Nalini, newly arrived aboard the shanghaied ship, serves as the outsider-observer. She attends an event at which the audience rejects its own sensory experiences. “They glowed, intoxicated by the act of publicly proving their faith to be stronger than what they all saw with their own eyes. Nalini had no word to capture their response. But hers was horror.”

This sounds familiar to anyone who’s lived in the U.S. since at least 2016, but more specifically it reads like a reflection of the nation’s polarized reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic — half the country seemingly bent on seceding from scientific reality.

In fact, Johnson wrote the book in 2017 and 2018. After that, it sat in his drawer while, for three years, the author wrote nothing at all. He was too distracted by a crisis far more personal than the social divisions around him. Just as Johnson’s mother’s health began to fail, his wife began undergoing treatment for a brain tumor. His mother died earlier this year; his wife recovered, and her prognosis is good.

Johnson calls those pre-pandemic years “the lowest period of my life. Everything was going wrong. … I could sleep for about an hour and a half and then I'd wake up for three hours and then sleep another hour and a half and then I'd be tired all day.”

They lived in Texas at the time; their move to Oregon enabled the family to recover both physically and financially. Another factor was a sense of looming racial animus — everything from an increase of MAGA hats to a classmate hurling racial slurs at his daughter on the school bus.

Oregon suits Johnson, even if the vast majority of its inhabitants are white. Portland, in fact, reminds him of his old Philly neighborhood, Germantown. “The white liberal population of my part of Philadelphia is almost identical to [Portland]. They share the values, which, as much as they get commonly ridiculed, are really important to me.”

The country at large, meanwhile, is no utopia. By the time Johnson emerged from his family crisis to put the finishing touches on the book, the world had warped to look even more like the one he’d invented — from antivax hysteria through the Black Lives Matter protests and on to the Jan. 6 riots. In writing the novel, “I came up with a metaphor that was absurd and now it's just normal. It was really bizarre, but I went from ‘Oh, my God. I called it’ to ‘I'm being outstripped by reality. This is horrible.’”

Yet even if American society is turning dystopian fiction into a sucker’s game, “Invisible Things” feels au courant. Not only does Johnson seem to capture the chaos of the 2020 election, with the losing side insisting that everything is fake, but it also predicts the backlash to the 1619 Project and the wave of book bans that followed. I asked him whether its author, Nikole Hannah-Jones, was an influence; he was not surprised by the question.

“I’ve noticed with the 1619 Project and the BLM movement that a lot of my white peers are asking me how my work would change,” he said. “It’s not. I’ve been living there my whole life. The biggest difference to me was there was such a white reaction. Hannah-Jones’ brilliance was putting it down and articulating a worldview, but the worldview” was already there.

Johnson hasn’t been alone in doing that continuing work through genre fiction. LaValle, Percival Everett, filmmaker Jordan Peele and others have helped recast the role of the protagonist in thrillers, satires and horror films as someone other than white. “I was just talking yesterday,” Johnson says, “about how Black men are such a center of fear in American culture that the idea that Black men can actually get totally scared is still revolutionary.”

Despite his focus on a culture moving at warp speed toward the farthest reaches of absurdity, talking with Johnson is comforting. It feels like being in the presence of an inveterate optimist. During our conversation, we pull out the invisible things from the existential grab bag and look at them until we can see them, name them. Talking about them makes them less scary — helps us believe for a moment that, as one of his characters says, we can “start acknowledging reality, and face our problems, together.”

Suddenly, three hours have passed and Johnson has an Amtrak to catch back to Portland, where his family will expect to share Friday-night pizza. He heads out to remount his bike. I wave goodbye as he pushes off like a cheery Einstein into a bizarre late-May mixture of rain and sleet — a scene as ordinary and apocalyptically surreal as his fiction, or America in 2022.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.