Matrix would use data to help decide if Lexington needs to move development boundary

A task force looking at data-driven ways to determine when Fayette County should open more land to possible development has sent a matrix to the Urban County Planning Commission for its review.

The Sustainable Growth Task Force voted unanimously Wednesday to give the matrix to the planning commission for its review.

The methodology has been criticized by some in real estate, development and the area’s biggest business organization as overly complicated. It doesn’t address current demand in the housing market, some critics say.

The planning commission could start initial discussions on the proposal as early as Sept. 16, which will allow time for more education and to beef up the explanation of how the framework was developed.

There will be public hearings — to allow the public to weigh in on the matrix — before the commission votes to approve or change it, city officials have said. The plan commission will not be voting to open or keep the current growth boundary. Outside the boundary, last changed in 1996, development is prohibited.

During debate on the 2018 Comprehensive Plan, which determines what types of development can go where, the city decided to decouple from the plan the thorny, contentious question of when to move the growth boundary.

To do that, the city wanted a data-driven analysis of vacant land and the city’s long-term needs.

Stantec, an engineering consulting firm, was hired in August 2020 to provide that analysis.

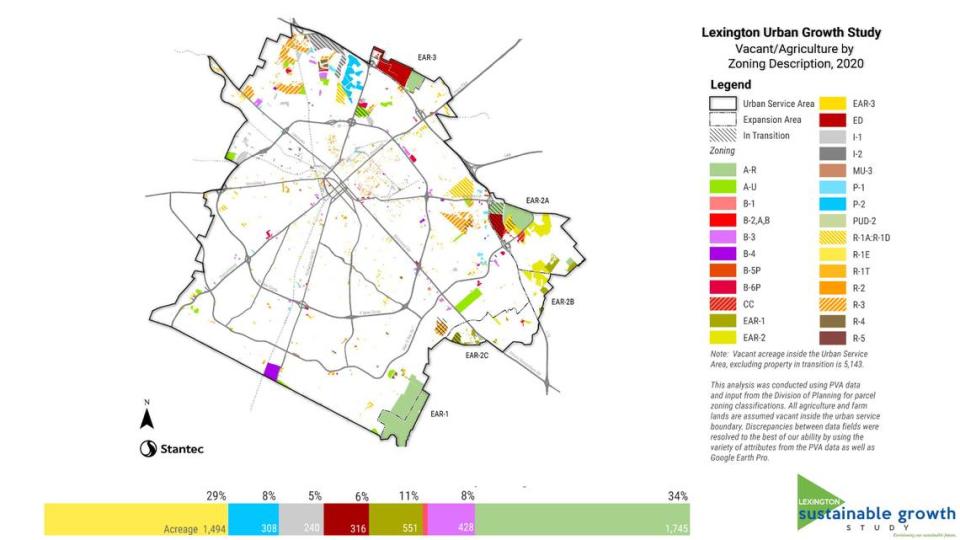

Stantec looked at current vacant and agricultural land and also did a deep-dive analysis of both past and future housing, commercial, retail and industrial real estate trends to determine future needs.

“This study does not explicitly study various expansion alternatives,” said Mark Butler of Stantec during a Monday public meeting. “We are focused on the question: Does the land inside the current service boundary allow for more growth?”

Butler said Stantec focused on readily and easily attainable data so the city can track the trends over time.

“The data has to be accessible and easily repeatable,” Butler said.

Vacant land versus housing, commercial needs in 20 years

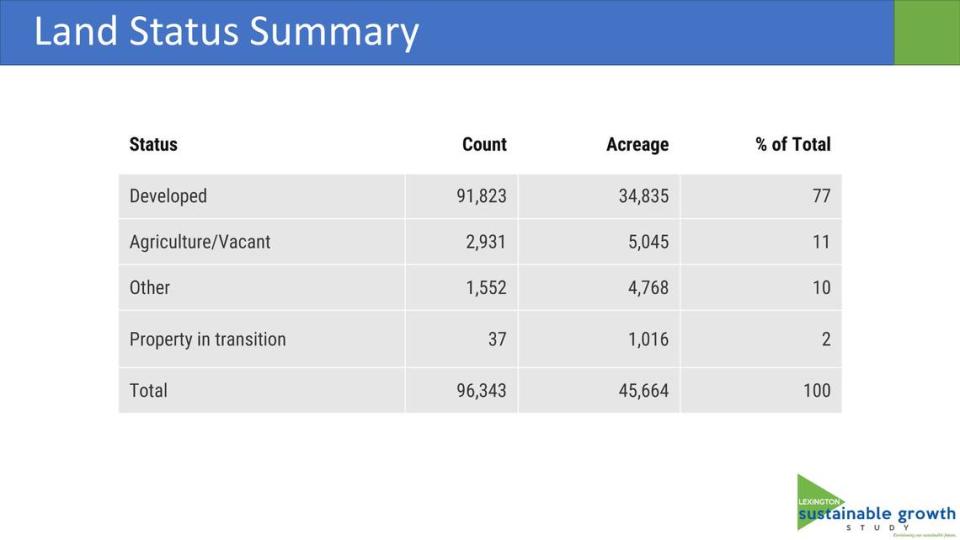

That Stantec analysis showed:

There are currently 5,045 acres of vacant and agricultural land inside the urban service boundary or the growth boundary.

In addition, there are 1,016 acres of property in transition. That means the property is either currently being developed or there have been development plans submitted. Included in that total is approximately 200 acres of land that will transfer to the city in 2022 for a new industrial park off of Georgetown Road.

Over the next 20 years, the number of housing units needed will be between 27,900 on the conservative end to 41,200.

In the same time period, 2.5 million to 4.5 million square feet of additional office space, and 2.2 million to 5 million square feet of additional retail space will be needed.

Over the next two decades, 1.3 million to 5.6 million square feet of additional industrial space will be needed.

Next, the Stantec team looked at three different scenarios for how development could occur.

The first scenario, the most conservative, is based on current development patterns. That scenario means more single-family homes and fewer commercial, industrial and mixed-use spaces. Mixed-use spaces are a combination of retail, residential and/or office space.

The second scenario follows the guidelines of the 2018 Comprehensive Plan, which encourages more dense development, particularly on the city’s main corridors, such as Nicholasville and Versailles Roads. More dense development typically translates to more apartments and townhouses than single-family homes.

The third scenario included more dense development and some redevelopment of current properties inside the current growth boundary.

Under scenario one, the most conservative growth estimate, the city would not have enough land to meet 100 percent of demand in the lowest estimate or 75 percent of the highest estimate of 41,200 housing units.

Under scenario two and three, which includes more dense development, the city would have enough vacant land for housing.

Under scenarios one and two, the city would have enough land available to meet the lowest projections for future demand for industrial square footage, but it would not have enough land if demand tops 4.2 million square feet or 75 percent of the 5.6 million square feet.

Under the third scenario, Lexington would have enough land to meet the lowest projections and 75 percent of the highest projection.

The current available land could meet the demand for office and retail space in all three development scenarios, according to the proposed matrix or framework.

The city will have to track the available land and look at land-use trends every year to determine if the city is growing like described in scenarios one, two or three, said Craig Bencz, a city senior staffer who is helping oversee the work of the task force.

During a Monday public meeting, several members of the development community questioned some of the assumptions Stantec used to develop the matrix and data-driven analysis.

Too confusing? What about housing?

Gina Greathouse, executive vice president for economic development for Commerce Lexington, the city’s business chamber, said the matrix is too confusing.

“We find it very difficult to understand this framework,” Greathouse said.

The Stantec analysis also doesn’t factor in the current demand for housing. Lexington and the surrounding counties are in one of the tightest real estate markets in decades. There are too few homes for sale or being built to meet the demand, said David Hill, a real estate agent. That’s causing housing prices to surge, pricing many homeowners out, real estate officials said.

“Higher density, small multi-family units is not what homeowners are looking for,” said Hill.

Nick Nicholson, a land-use lawyer who represents many developers, said higher density sounds good in theory. However, experience shows Lexington neighborhoods fight high-density apartment and mixed-use retail and residential spaces.

“They fight infill at every turn,” Nicholson said.

Although more than 5,000 acres of vacant land sounds like a lot, landowners may be unwilling to sell, and the analysis does not take that into account, several from the development community said during Monday’s public hearing.

“The most unrealistic (assumption ) is the assumption that the vacant (land) is usable,” said Todd Johnson, executive vice president of the Building Industry Association of Central Kentucky, the local home builders association.

“We have a housing shortage at every price point,” Johnson said.

Butler said it would be impossible for the analysis to know what land is available for sale and what is not, he said.

Brittany Roethemeier, the executive director of the Fayette Alliance, said in 1996, the last time the urban service boundary was expanded, the city added more than 4,000 acres. Less than half of that land has been developed, she said.

Roethemeier said a study done after that expansion showed that land-use policies are not affecting home prices.

“Lexington’s land-use policies do not appear to be currently causing housing prices to grow faster than prices for the state, nation, and comparison cities. One reason for this might be the availability of land in surrounding counties,” the 2017 University of Kentucky study concluded.

“There is no question that we are growing. The question is how we want to grow?” Roethemeier said.

During Wednesday’s meeting, members of the Sustainable Growth Task Force — including developers, planning commission members and residents — agreed that it would provide additional information on the task force’s work and how Stantec identified vacant available property.

The task force also recommended beefing up the final report to make the complex framework more easily understandable to the public.

Stantec’s existing conditions report, which identifies housing, commercial and other trends, is available at the Sustainable Growth Task Force website at lexsustainablegrowth.mysocialpinpoint.com.