Matthew and Florence have left Fair Bluff businesses with two needs: space and customers

On any given day, Micheal Green can be found simultaneously in two separate locations around downtown Fair Bluff.

At 1122 Main Street, in the heart of the Columbus County town’s virtually deserted commercial district, a painting of Green hangs on the wall, a wide grin visible through the windowless store front. The painting’s eyes gaze over mud-caked detritus strewn across the floor of a shop, which suffered severe flooding during 2016’s Hurricane Matthew and again during 2018’s Hurricane Florence.

“The town, when I ride through it, it’s a place that’s sad. It’s like a ghost town. A lot of the businesses are not there,” Green said recently from the other place where he is often found: a kiosk tucked into the front corner of the only Fair Bluff gas station, just past the soft drink coolers and just before the bathrooms.

There may not be a painting on the gas station wall, but since early June, a banner has declared MikeMike’s Computers open for business.

Hurricanes Matthew and Florence caused billions of dollars in damage throughout Eastern North Carolina, flooding homes and businesses throughout towns like Fair Bluff. Now, years after Matthew and months after Florence, many of those businesses are struggling to stay open — and it’s not clear if they can surmount the dual obstacles of a dwindling population and damaged building stock.

The true impact of the storms on businesses is also unclear, as neither the N.C. Department of Commerce nor the federal Small Business Administration are tracking closures in hurricane-impacted counties.

What Fair Bluff’s government is tracking, albeit in a round-about manner, is population loss. Al Leonard, the town’s part-time town manager, uses water and sewer consumption to estimate that the town’s population has dipped from about 950 in 2010 to about 600 after Matthew and Florence.

“If the folks are not here, then there’s no reason for a business to open here,” Leonard said during a recent meeting in Fair Bluff’s new town hall, which was built after the former Main Street location flooded in Matthew.

Understanding the potential loss of population and building it into projections is a complicated part of surviving hurricanes, said Hallie Hawkins, a strategy, growth and sustainability counselor at the Small Business and Technology Development Center at East Carolina University. Hawkins worked with 12 counties in Eastern North Carolina following Matthew and Florence, including hard-hit Craven and Jones counties.

“Your community,” Hawkins said, “might not be able to support you in the way that it used to.”

That is particularly true in Fair Bluff. In early June, the Ply Gem plant on the town’s southern end notified officials it was closing Aug. 2 for reasons unrelated to the floods, resulting in the loss of 58 employees. The plant has in recent years manufactured fencing and roofing products.

In addition to the layoffs, the closure means Fair Bluff will soon lose its largest water and sewer customer, with officials calculating they will lose about $1,200 a month in utility payments. To recoup the lost revenue, the Fair Bluff Town Council voted to raise water and sewer rates from $64.45 per 2,000 gallons to $68.45.

While they felt obligated to raise the rate, town officials are worried about residents in their hurricane-damaged town’s ability to pay. Leonard said, “I know the people here are struggling, and I know $4 doesn’t seem like a lot. But when you’re on a fixed income it is a lot, and usually that income is maxed out, so I am concerned.”

Twin disasters

Prior to this decade’s hurricanes, Fair Bluff hadn’t suffered catastrophic flooding in nearly a century.

According to a history of the Lumber River Basin compiled in 1978 by a pair of St. Andrews College archaeologists, “The Lumber River flood, which occurred in 1928, was the worst in the history of the town. In that same year, the first paved road in the area, Highway 76, was constructed through the town.”

The following century saw homes built in Fair Bluff and the town’s Main Street depicted as an idyllic example of a Southern small town.

Leonard says the town was lulled into complacency. The Lumber, which runs just behind Main Street, sometimes swelled beyond its banks, but it never spilled into the homes and businesses that slowly rose along Main Street.

“No one really knew how devastating the flooding could be here until Matthew hit,” Leonard said.

Green, a Fair Bluff native who opened his computer shop on Main Street in 2011, was among those who did not foresee the potential impact of a flood.

“We’ve always been near the river, but it’s never flooded, at least not in my lifetime,” Green said recently, referencing the period before Matthew and Florence.

After Matthew, Green told the News & Observer he had lost about $50,000 worth of computers and office supplies.

Then, in September 2018, came Hurricane Florence. Fair Bluff was in the midst of playing what Leonard calls “the grant game” -- applying for different pots of money to help the financially beleaguered town make necessary repairs to infrastructure and work to bring its residents back.

Matthew’s floodwaters spilled as much as four feet of water into Fair Bluff homes and businesses and lingered as much as two weeks, Leonard recalled. Florence’s floodwaters impacted virtually the same area, standing as much as four inches higher but receding much more quickly, in about eight days.

Al Hammond has been Fair Bluff’s mayor for about five years; he’s tried to lead the town through the two worst disasters in his lifetime.

“I never thought,” Hammond said, “it would happen twice in 23 months.”

A state assessment for Hurricane Florence estimated that businesses and nonprofits statewide suffered $5.7 billion in damages, with 3,800 suffering water damage and more than 23,000 having wind damage.

Flooding’s impact

It is easy, when walking down Fair Bluff’s Main Street, to feel like an interloper. There are signs of a town trying to survive — saplings in pots, flags touting late July’s annual Watermelon Festival.

It could, however, take as much as two hours to see another pedestrian. And curtains in a window facing the well-manicured Fair Bluff Baptist Church are spotted with black mold spores.

According to U.S. Census estimates, Fair Bluff’s median household income in 2017 was $27,898, and about one in every five households were living below the poverty line. Even before the floods hit, town leaders said, Fair Bluff was faltering.

“The businesses we had here were very marginal,” Leonard said. “They were struggling.”

When Matthew’s floodwaters receded, Leonard recalled, building owners returned to Main Street with the hope of mucking out the stores and returning to normal operations.

Upon entering the stores, though, the owners discovered that two weeks of water had rendered the buildings ruined beyond a point worth repairing. And then the disaster was repeated during Florence, reemphasizing the risk anyone would take in opening a business on Main Street.

Leonard said, “The question would be if someone wanted to open a business in Fair Bluff — a beauty salon, we had a doctor’s office downtown, we had a drugstore — if somebody wanted to open one of those, where do they go? And there’s no place for them to go.”

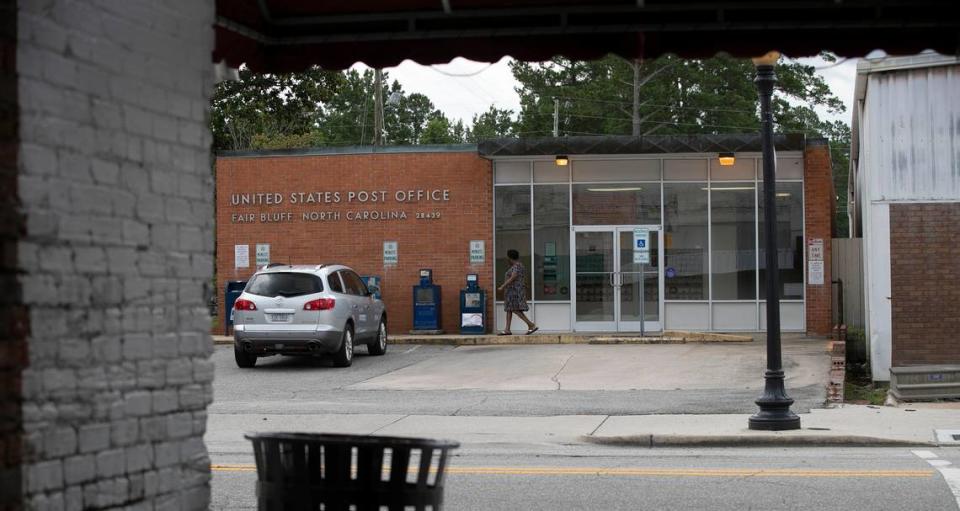

Green is one of the few people with an answer to Leonard’s question, along with the U.S. Post Office and a used car dealership.

When he found himself spending much of his day at the gas station, greeting people he knows as they stopped in, Green asked the owner if he could do computer work there, which soon led to him setting up the kiosk.

“There’s not many locations in Fair Bluff to do that, building-wise,” Green said.

Problems and resources

The problem Green faced is not isolated to Fair Bluff or any other part of the state. Hawkins, the ECU sustainability counselor, said she is working with a business around New Bern that can’t find a building with sufficient space for its operations.

Businesses face a multitude of problems after storms, according to officials from ECU’s small business center and Thread Capital, which have spent much of their time since October 2016 aiding owners during the recovery process. Preparing small businesses for disaster recovery is, officials said, one of their key missions.

Ariana Billingsley, the executive director of the ECU small business center, said the demands of running a small business often mean the owner ends up taking on a multitude of tasks that need to be done immediately. Frequently, that does not include writing a plan for how the operation will continue after a disaster.

“It gets pushed until it needs to be done,” Billingsley said. “And at that point, it’s too late.”

As part of its counseling of disaster-impacted businesses, the small business center has stressed the importance of having a plan, including elements like having a list of employees with contact information, keeping an invoice list that is available online and maintaining a digital set of processes and procedures.

Then there’s concerns about money.

After a disaster, businesses have to worry not only about recovering, but also about continuing.

To that end, Thread Capital offers a pair of loans. Thread is the lending subsidiary of the N.C. Rural Center, a private nonprofit that works to bolster the state’s rural economy.

Until the end of January 2019, Thread offered a six-month no-interest loan of up to $50,000. That loan was intended to keep businesses running while they waited for Small Business Administration loans or insurance payouts.

Since Hurricane Florence, the SBA has approved 799 applications totaling $57.54 million for business disaster loans in North Carolina. The agency has also lent $9.17 million to 167 North Carolina businesses to cover operating costs.

After Florence, said Shannon O’Shea, a senior program manager at Thread, “A third of the state was practically closed down for weeks in some places, closer to months in others. So they had no revenue coming in, but bills were still due, so you keep getting squeezed tighter and tighter and tighter.”

In the longer term, Thread is offering a different loan meant to help disaster-impacted businesses become more resilient. Thread is offering a 10-year loan of as much as $250,000, with interest rates of 4.99% to 9.99%.

“The biggest thing that we shifted our mindset on in the last year or so is the idea that this is a once-in-a-generation storm, or once every 20 years. We now assume that the next one is two years away,” said Jonathan Brereton, Thread’s executive director. “If these businesses have any chance of surviving, they have to be proactively planning for that.”

Businesses that have taken the recovery loans, Thread officials said, have used the funds to increase or switch the insurance on their business; to ensure they have sufficient working capital on hand to withstand a disaster; and, in one instance, to help pay for a building’s elevation.

Helping businesses that are often already struggling make a major switch can be difficult, especially because they often remain vulnerable while changes are underway.

Brereton said, “That’s a little scary because if the next storm comes and they’re not prepared, there goes our money. But from a community development standpoint, which is what we’re trying to do, it’s pivotal that we’re there to help them make those adjustments.”

Hanging on

For Green, making that adjustment has meant finding a new location for his MikeMike’s computer repairs. After his shop flooded during Matthew, Green made every effort to stay in Fair Bluff. And while he once wondered if the town’s realities would force him to leave, Green never gave up.

“I just feel a different pulse,” Green said, “a different heartbeat when I’m there.”

Green knew almost every person who stopped by the Shop and Save on a recent day, the kind of familiarity that lets Green accurately note an elderly man hadn’t noticed Green’s greeting because he didn’t have his hearing aids in.

Earlier in the day, Green had helped a nearby church repair its sound system. And that evening, he would drive about 20 minutes to Chadbourn to help someone there with a computer problem.

The gas station kiosk will work for now, but Green’s long-term vision is a little more ambitious, especially in Fair Bluff at this point in its long history.

“I want to eventually get a storefront.... I would do it downtown if the opportunity came about, yes, or somewhere else in Fair Bluff,” Green said.

Hammond and Leonard recognize it is unlikely that downtown Fair Bluff will ever return, so they are planning to apply for a U.S. Economic Development Administration (EDA) grant that would fund a new retail space. Leonard said they are eyeing a spot that didn’t flood in Florence or Matthew and would need to be annexed into Fair Bluff.

Should the project come to fruition, Leonard and other town officials envision six to eight storefronts side-by-side, potentially more like a strip mall than Fair Bluff’s traditional downtown. But they have just started working on the grant application, which they anticipate finishing in about a month.

And Fair Bluff can’t afford a 20 percent grant match on its own, so it successfully appealed to the N.C. General Assembly to include a $6 million appropriation for the town in the state budget, of which $1.2 million would be used for the EDA match. Those funds have not been allocated due to the Medicaid expansion-centered budget stalemate between Gov. Roy Cooper and legislative Republicans.

“Right now, we don’t have any match money, and we don’t have a grant,” Leonard said. “All we’ve got is a plan.”

This story was produced with financial support from Report for America/GroundTruth Project, the North Carolina Community Foundation and the North Carolina Local News Lab Fund. The N&O maintains full editorial control.