‘Maus’ Author Art Spiegelman: ‘We Are on the Brink of Fascism’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In Robert Coover’s novel Street Cop, published in June of this year, the American writer depicts an askew, raunchy, weirdo-yet-not-entirely-unfamiliar world in which “everything was tentative and illusory”: a place where murderers are arrested by robots, the clocks are unreliable, the police vans are self-driving, there’s a pet shop of the living dead, and a quite literally mutating urban landscape in which the streets are paved in recyclable thermoplastics and neighborhoods deviously interchange locations.

The title character, when first encountered, is not an officer of the law but rather “a mere derelict, a nuisance really” who himself was being hotly pursued by the cops. Deciding in defeat to turn himself in at a police station, he instead emerges with a street cop gig the sergeant assumed he was applying for (the interview consisted of being asked to describe the first time he got laid). He “walked out in uniform, joined the hunters chasing a phantom.”

Street Cop is published by the independent outfit isolarii. Their subscription-based model of ultra-portable—iPhone-sized—editions is nimble; their editorial thread is compelling (their latest title being a correspondence between Édouard Glissant and Hans Ulrich Obrist.) The duo behind isolarii approached maestro cartoonist Art Spiegelman to visually pair with Coover’s postmodernist novella.

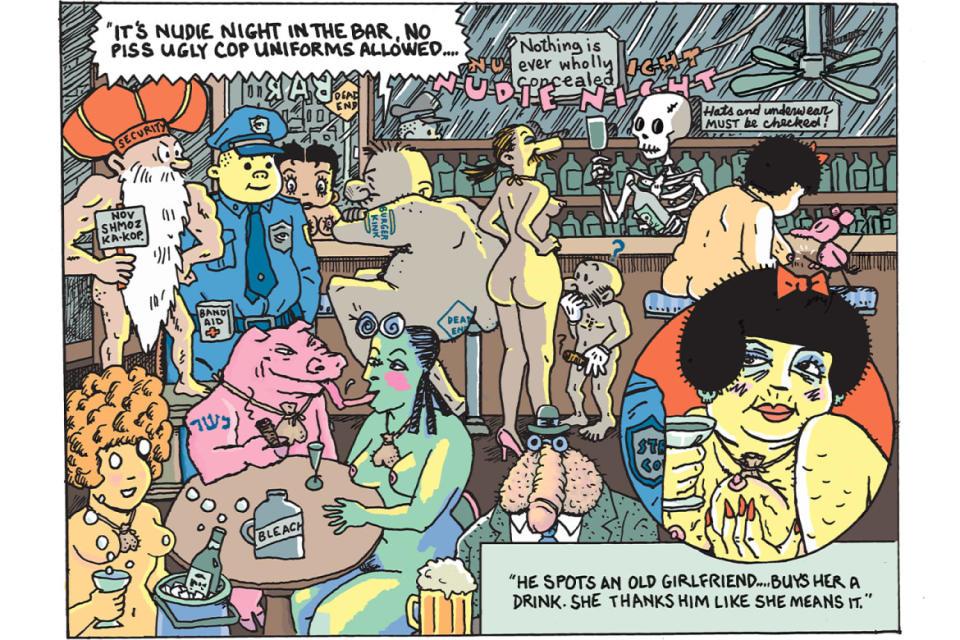

Spiegelman read the story and was attracted to Coover’s mélange of genres: crime, Western, science fiction, gothic tale, monsters, romance. He had carte blanche to do anything: “If you don’t like the story, draw whatever you want,” he was instructed—anything was permissible. Since there was no thematic connection to mice or to Jews—which he has felt tethered to in the wake of his epic and Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel Maus—he was game.

In recent years, Spiegelman has been occupying himself by writing essays and illustrating erotic poems. Thus, this endeavor was “learning to draw again… trying to get my hand not to be frozen,” as he described it during a talk he gave at the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme in Paris, during which he switched between his native English, heavily accented French, and puffs on an electric cigarette. At the time of isolarii's approach—“during the COVID ‘vacation’”—he was living “in a bunker in the woods” in Connecticut to retreat from the pandemic, nesting with his wife, Francoise Mouly, and their adult daughter.

Drawing returned him to the comics of the early 20th century: using an economy of form to say a lot. “I didn’t want to illustrate, I wanted to inhabit,” he said. Returning to his youthful cartoonist vibe felt “revitalizing.” From 1993-2003, he did covers for the New Yorker, but “it’s not my vocation,” he said. His interest in having to comment on current affairs waned, although “I see the New Yorker over the shoulder of Francoise,” he said endearingly of his wife, the longstanding art editor at that prestigious publication.

Spiegelman initially considered his preliminary sketches for Street Cop “stupid, useless, brutal”—but when the Paris-based Galerie Martel, which specializes in illustration and comic arts, asked to display them, he acquiesced. It “changed my brain” to think of them as drawings unto themselves instead of “notes,” Spiegelman admitted. (Everyone else’s brain required absolutely no changing: There was a line of over 25 people on rue Martel at 3 p.m. on a brisk Monday afternoon in November, fretful to see the exhibition as soon as it opened and get books signed, as the French edition had just been released by Flammarion.) Spiegelman’s studies for the book’s visuals, on display at the gallery until Dec. 4, are a delightfully dynamic, frenetic, spirited array—images in various stages of kaleidoscopically colorfully swirling, messy, disheveled scrawl. There’s also a small selection of unpublished New Yorker covers.

“Comics are an art of communication,” Spiegelman said, standing firmly in contrast to so-called “high art.” In the past, “communicating too easily was considered commercial,” he noted, but countered simply: “I think art is anything that gives shape to your thoughts or feelings.” He waved off the reverence for obtuse artists, finding them “masturbatory.” This, nonetheless, is the kind of art he feels is valorized today.

“Cartoonists are gone,” Spiegelman said. “Humor has become more and more dangerous… Pictures are dangerous.” Editors fear “different interpretations,” he lamented: “Newspapers want to keep every reader they have—so it’s better to talk to the stupid ones.” He concluded: “Every time someone says something satirical, they get cancelled.”

“How do you tell a story of violence without perpetuating or participating in that violence?” a member of the audience asked him. His own relationship to violence is squeamish, Spiegelman explained. His father wanted him to be a doctor, but Spiegelman majored in philosophy before he got kicked out of school. Since he was scared of blood, his dad suggested dentistry as an alternative. (“I have a much better relationship with my father now that he’s dead,” he joked.)

“My approach to violence was to show as little as possible,” Spiegelman clarified. He separates himself from the “Grand Guignol” aspect of its spectacle. Even in Maus, when his father recounts hearing Jewish children were grabbed by their feet so their heads could be smashed against the wall, Spiegelman found a subtle way to accompany this horrifying recollection. He used a comic bubble as camouflage, turning the anecdote into an abstraction—underlining, moreover, that it was something his father heard about, but didn’t witness directly.

New kinds of violence feel pervasive in today’s world, inflected by a different cultural tenor—in the United States especially. He admitted to being stuck on how to draw a scene from Coover’s book with a shifty, menacingly modular government building—until the insurrection at the Capitol on Jan. 6 created an “Aha” moment on that front. “I have Trump to thank for that—and nothing else,” he said dryly. “In North America, we are on the brink of fascism—if the Trump party wins, you’ll see a lot more of me in France than you want.”

There is an eerie, chilling bridge between the dystopia of Coover’s fiction and the ugly socio-political reality of America today. “The future had melted into the present, because it’s like science fiction anyway,” Spiegelman said. “We are living in dangerous times.”

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.