There may be fewer than 1,000 of this NC bird left. What it will take to save it.

A coalition of environmental groups are asking the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to declare endangered a coastal bird that breeds in North Carolina and some neighboring states.

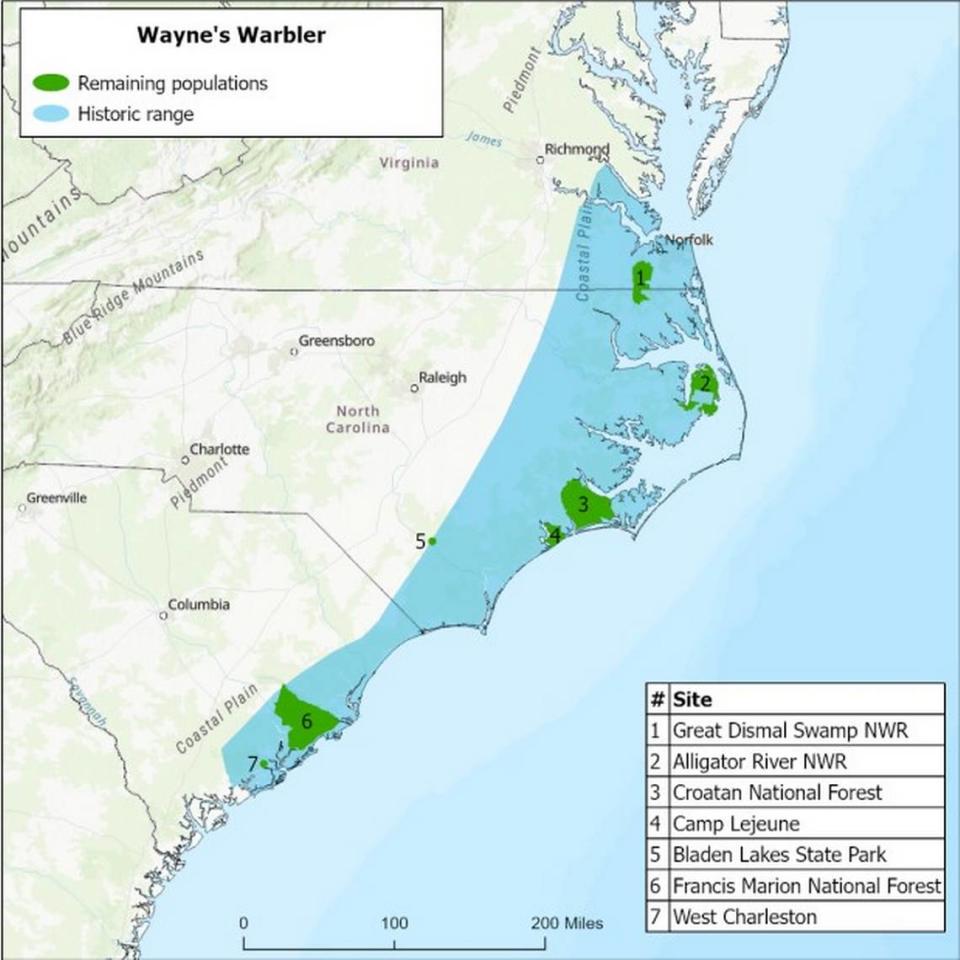

Coastal black-throated green warblers are a small subspecies of birds that have historically had breeding grounds in wetlands in the coastal plains of North Carolina, South Carolina and southeastern Virginia.

As those wetlands have either been cleared of trees, flooded or developed, the bird’s range has steadily declined, said the coalition, which includes the Center for Biological Diversity, Coastal Plain Conservation Group, Dogwood Alliance, N.C. Coastal Federation and two chapters of the Audubon Society.

“It was already very, very habitat-specific and due to the biomass industry, due to climate change, due to various anthropocentric factors, that already highly specific habitat has become even more fragmented, even more seldom,” Soleil Gaylord, a Center for Biological Diversity scientist, told The News & Observer.

How many coastal green warblers remain?

There could fewer than 1,000 coastal black-throated green warblers left in the wild, according to the Center for Biological Diversity petition, which also says conservative estimates top out around 2,200 birds.

Their traditional range is between southeastern Virginia and Charleston, South Carolina. But now, the bird is only found in seven areas in the region:

Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge

Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge

Croatan National Forest

Camp Lejeune

Bladen Lakes State Park

Francis Marion National Forest

West Charleston.

In the petition to list the bird as an endangered species, Carpenter is quoted as saying that he would be “cautious about using the word stronghold” about these areas because the bird’s populations are sparse, even where it is found.

The birds are also migratory, but scientists aren’t sure where they fly to in the winter months or how habitat there could be affecting the bird’s population.

How this bird is different from its more common relative

The coastal black-throated green warbler is also known as the Wayne’s warbler, a nod to the person who first described it in 1909. It is a subpecies of the much more common black-throated green warbler.

The more common bird lives in a broad range throughout Canada and in the Appalachian mountains, where the subspecies is exclusively found in coastal areas around North Carolina.

John Carpenter, the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission’s eastern landbird biologist, conducted genetic work that found the bird is genetically distinct from the more common warbler.

“We found enough differences to say, ‘Something happened.’ We’re kind of peeking into evolution occurring in real time, in a sense,” Carpenter told The N&O.

Coastal black-throated green warblers are also slightly different in appearance, the petition said. They are smaller than their relatives, with smaller beaks and smaller black areas on their chests.

But, Carpenter said, those differences likely aren’t obvious without careful observation.

“Their song and their overall appearance are very similar,” he said. “They just haven’t been separated enough for a long enough period of time for them to start sounding different or even looking different.”

Why the coastal black-throated green warbler is threatened

The wetland hardwood forests where the coastal black-throated green warbler lives are disappearing, threatening the species’ survival.

“Loss of habitat is the key factor contributing to their decline,” Joe Poston, a Catawba College biologist who was part of the warbler’s genetic study, told The N&O.

NautreServe, a nonprofit that works on biodiversity, reported that less than 5% of the land within the coastal black-throated green warbler’s range is excellent or good habitat for the bird.

According to the petition, logging is a main reason for this, particularly for the wood pellet and pulpwood industries. Wetland forests are cleared of existing trees, the petition said, and after those forests are cleared, they’re often replaced by single-species pine plantations that don’t offer the same habitat for the warblers and other birds.

The bird is particularly fond of Atlantic white cedar trees, which were historically harvested for use in the shingle industry. According to the petition, there may have once been half-a-million acres of the trees, where today there are 125,000 acres.

“Climate change, pestilence, disease — all of those things are threatening the Atlantic white cedar. Unfortunately that does not bode well for the Wayne’s warbler,” Gaylord said.

Bald cypress trees also provide important habitat for the birds, according to the petition.

Climate change heightens threats

During his 2018 survey, Carpenter found that the coastal warbler is most abundant in the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge.

That low-lying area that sits just before the Outer Banks in northeastern North Carolina is particularly susceptible to saltwater, and the sea has risen about a foot at nearby Oregon Inlet since 1977, according to federal data.

A 2021 study from researchers at Duke University and the University of Virginia found that the refuge lost 10% of its forested wetlands to sea level rise between 1984 and 2019. That paper also found that about a third of the refuge had switched from forest to either marsh or shrub land.

Under an “intermediate” global warming scenario, federal officials project that seas will rise nearly four feet at Oregon Inlet by 2100. That could have dire consequences for the low-lying habitat that’s so important to the warbler.

“The projections have most of that refuge underwater by the end of the century, which would not be good for the forested structure that the Wayne’s warbler needs,” Carpenter said.

How an endangered species listing could help

The petitioners are asking the Fish and Wildlife Service designate swaths of the Southeast in which the Wayne’s warbler can be found as critical habitat, in addition to declaring the bird endangered. Additionally, the petition called for protection of migration corridors and surrounding habitat areas around where the bird can be found today.

“What we have is already so narrow and protecting the rest of what remains of that habitat is basically what this species’ existence hinges upon,” Gaylord said.

A critical habitat designation would prevent activities that require a federal permit, license or funding from taking place around areas the Fish and Wildlife Service deems vital to the bird’s survival. It would also prevent federal agencies from destroying or modifying the habitats.

Another warbler, declared extinct

In October, the Fish and Wildlife Service declared Bachman’s warbler extinct.

The bird had breeding grounds in coastal areas of both North Carolina and South Carolina, The N&O previously reported. It was last seen around Charleston in the early 1960s.

“Federal protection came too late to reverse these species’ decline, and it’s a wake-up call on the importance of conserving imperiled species before it’s too late,” Martha Williams, the FWS’ director, said in a press release at the time.

Similarities between the birds

Like the coastal black-throated green warbler, Bachman’s warbler lived in swampy forests in the Southeastern United States. The ivory-billed woodpecker, also known as the “Lord God Bird,” is on the verge of extinction and inhabits similar areas, the petitioners note.

“Without federal protection,” the petition said, “the coastal black-throated green warbler will continue sprialing toward extinction like Bachman’s warbler and the ivory-billed woodpecker.”

Poston, the Catawba College biologist, noted that he never had the opportunity to hear Bachman’s warbler, which was likely extinct before he was born.

“I’d hate for future generations not to know what it would be like to hear Wayne’s black-throated green warblers in the coastal plain,” Poston said.

This story was produced with financial support from the Hartfield Foundation and 1Earth Fund, in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners, as part of an independent journalism fellowship program. The N&O maintains full editorial control of the work.