‘Maybe we don’t have control over our destinies’: Touching stories from the class of 9/11

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It was just another day in the Quad Cities. Until it wasn't.

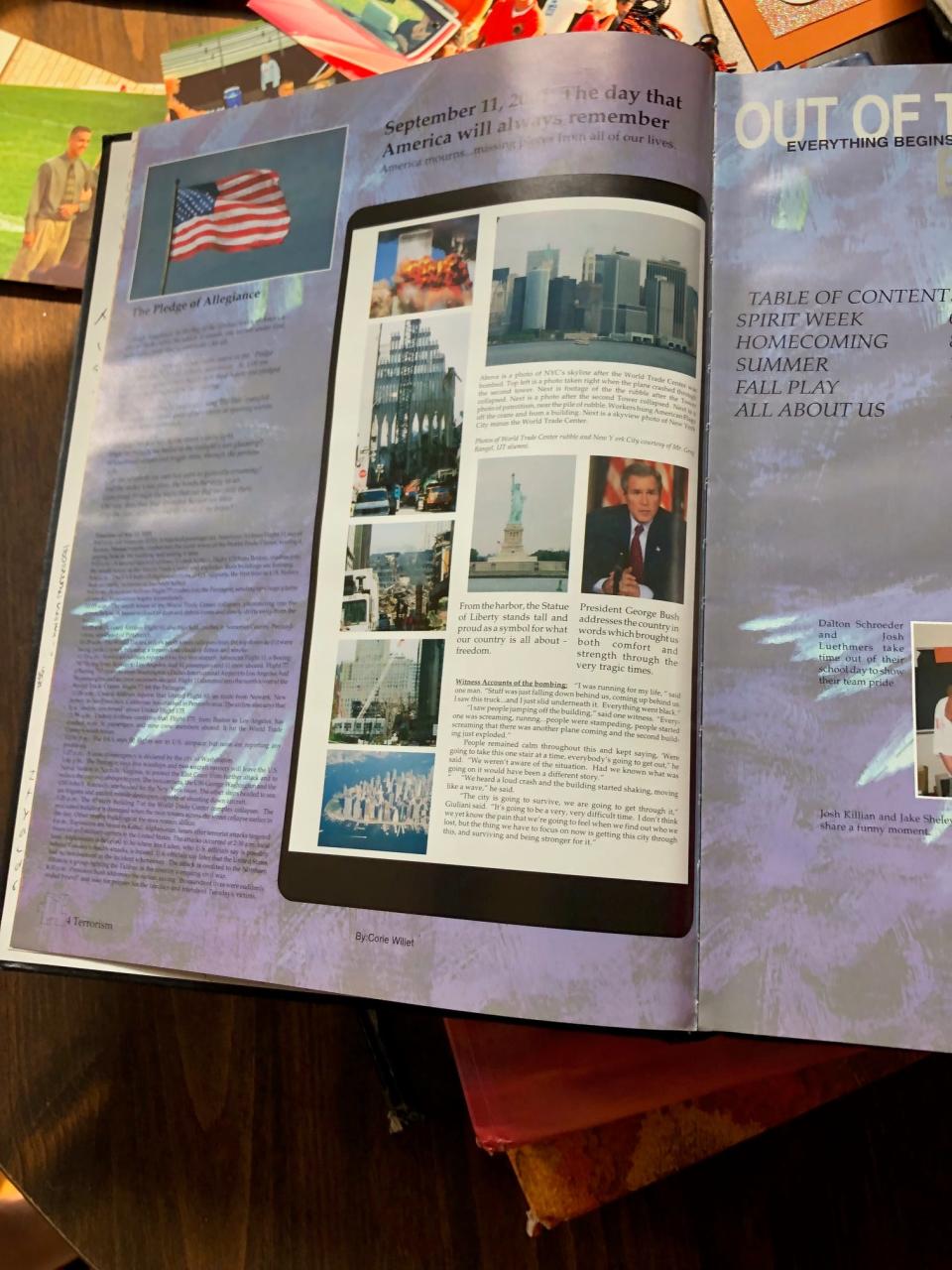

Nearly 20 years ago, as the senior class at United Township High School in East Moline, Illinois, prepared for homecoming, al-Qaida hijackers commandeered jetliners and crashed them into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon and a Pennsylvania field.

The terrorist attack killed nearly 3,000, crushed the U.S. economy, triggered two decades of war and transformed our politics, policies and lives.

For victims, families and first responders, the trauma and transformation has been calcified in their consciousness. What it meant to those of us with no direct connection to the attack may be less vivid, yet nearly as profound.

For high school students who were seniors on Sept. 11, 2001, it was a paradigm shift as they crossed into adulthood.

Was it a defining moment for millennials, just as Pearl Harbor was for the Greatest Generation or the Kennedy assassination was for baby boomers?

Andy Hughes, a linebacker and future cop, was convinced he wasn’t good enough in class or football to attend college, so he joined the military. His comrades were sent to Iraq while he was chosen to guard Marine Helicopter Squadron One, used by President George W. Bush to wage a war on terror. In the den at Hughes’ house, there is a souvenir rotor and a certificate “for honorable service in the White House.”

Amanda (Adams) Walters, a cheerleader, blushes as she remembers her initial reaction when she saw the towers attacked on a TV in the school library: She was distraught that homecoming week – the parade, football game and dance – might be canceled. Later, the brother she idolized was killed in a Marine Corps training accident as he prepared to deploy to Iraq, crushing her spirit.

Lambros Fotos, a wrestler, got a black eye in the 2002 Illinois high school wrestling championship, but in photographs, his arm is raised in triumph. The terrorist attack changed his mindset about world events and history, a subject he now teaches at United Township High.

Tess (Mahalla) Abney, the student council president, feared her boyfriend would get drafted and sent to war. She was voted “most likely to become president,” but a pregnancy waylaid political dreams. The son she bore graduated in the class of 2021, his senior year sabotaged by the coronavirus.

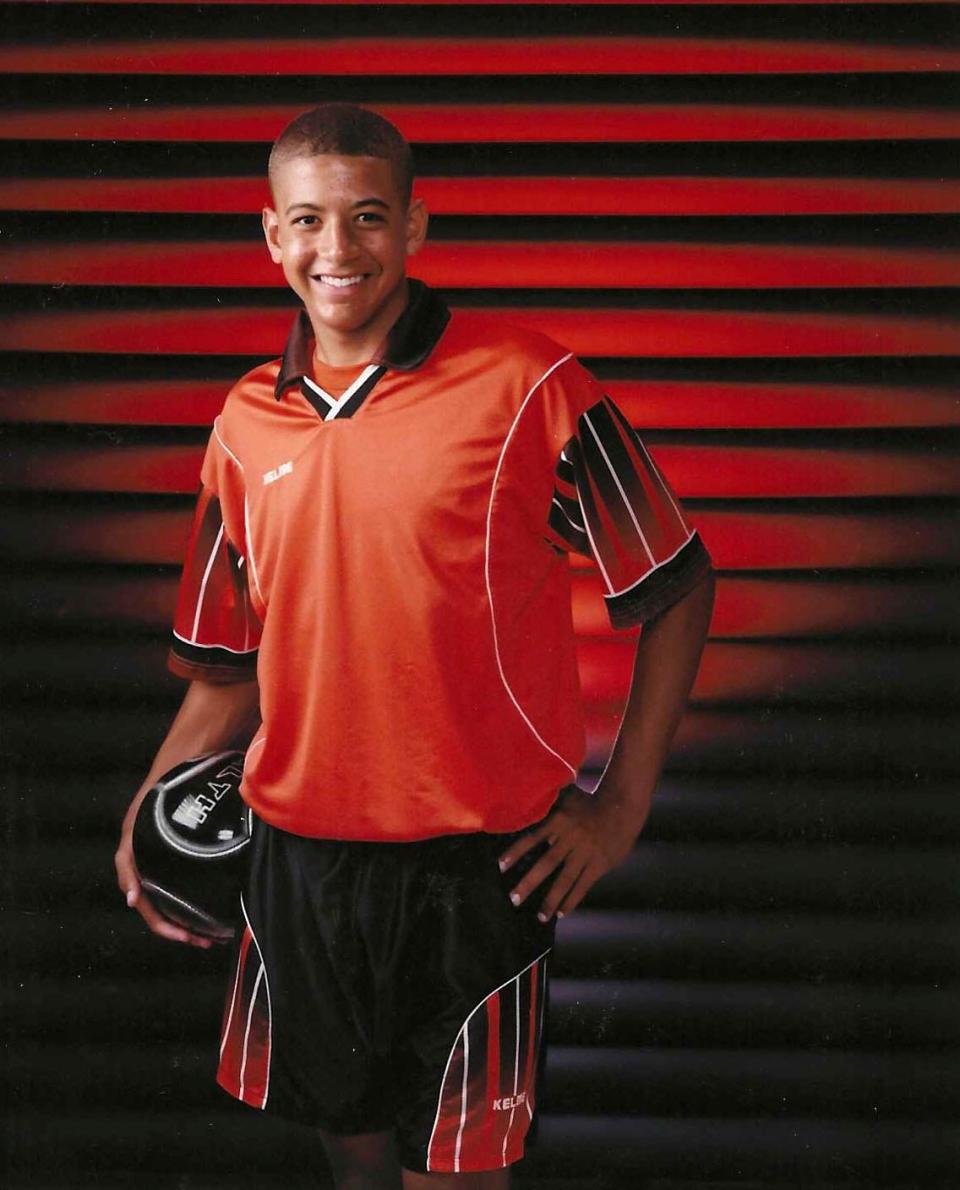

Dustin Freeman, a soccer player, needed one more win for a perfect season, but the final game was scheduled Sept. 11. "Everything kind of just stopped," he recalls. “Soccer was off. Everything was off for a while. … And we wondered, ‘Is this going to happen again?’”

Five students, now 37 or 38 years old, out of about 400 graduates in United Township's class of 2002.

Certainly, other mega-events buffeted them: the Great Recession, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the election of an African American president, the COVID-19 pandemic, Black Lives Matter protests and an insurrection.

Yet the vision of a second jetliner smashing into the twin towers – broadcast live on TV – was an unforgettable moment for all, altering the world in ways large and small.

Even at a high school in the nation’s breadbasket, where the first transcontinental railroad spanned the Mississippi River, lives changed, dreams died, eyes were opened.

The following spring, the Rock Island Dispatch-Argus published a story about the graduation ceremonies at United Township High. It quoted a speech from Joel Boerckel, co-valedictorian, who said he and his classmates were grappling with “the shocking realization that evil really does exist, and that maybe a two-story suburban home and SUV are not the only things that really matter. ... Maybe we don’t have control over our destinies.”

How much did the events and aftermath of Sept. 11 shape lives? There is no unilateral answer. Historical moments influence each of us uniquely depending on our backgrounds, DNA and degrees of separation.

And we know only what path we followed, not what might have been.

In one sense, 9/11 is a story of the USA. In another, it is a story of us – our memories, influences, trajectories. Not just for those who were in New York or Washington but for a bunch of kids far removed from the crash sites.

After the seniors signed their yearbooks and threw their graduation caps in the air, they went to college, found jobs, grew up. Many married and are raising kids of their own, chasing an American dream that is ever more distant, gaining pounds and losing hair.

But they can’t forget that day. Two decades later, each wears an indelible yet invisible imprint of 9/11.

A serene place

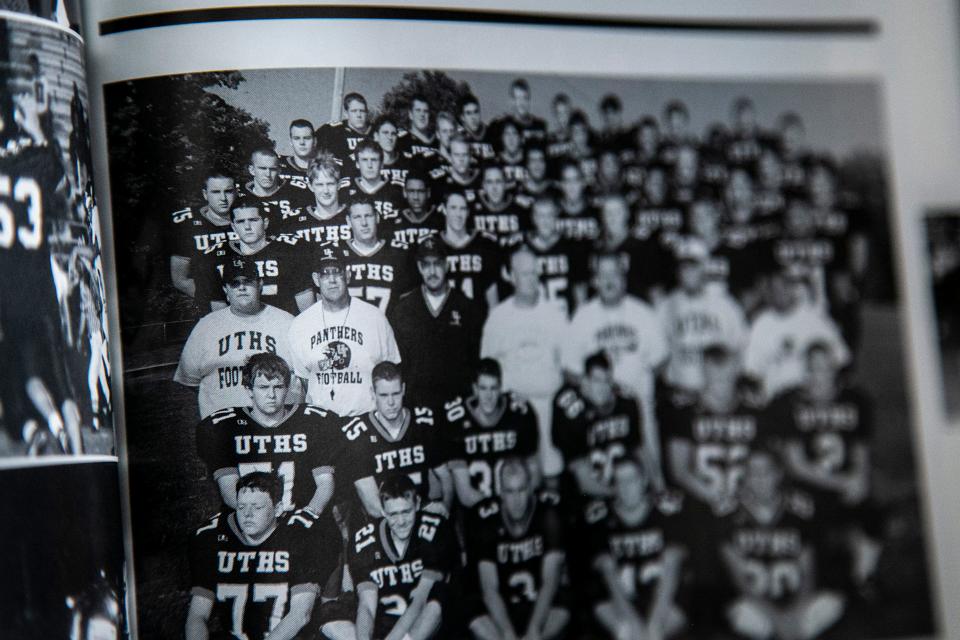

United Township High, home of the mighty Panthers (with Halloween school colors), sprawls at the corner of Archer Drive and Avenue of the Cities, a nondescript jumble of flat-topped buildings with nearly 1,700 students.

They call the area the Quad Cities, but there are more than a half-dozen towns. United Township High draws not just from East Moline but from Silvis, Moline, Rock Island, Carbon Cliff, Colona – communities along a river that splits the nation and connects two states.

The neighborhoods are largely blue-collar, with emerald-summer lawns that give way to fields of corn and soybean accented by forests and factories.

This is where John Deere tractors got started. It is home to meatpacking plants and Rock Island Arsenal, the U.S. military’s largest munitions center – industries that proved magnetic to immigrants, as reflected in the high school's demographics.

During the summer of 2001, United Township High students were among roughly 4 million American high school seniors just beginning to sense the independence and responsibilities to come.

It was the year Wikipedia got started, George W. Bush became president, Apple introduced the iPod and Train’s song “Drops of Jupiter” was a smash hit:

The al-Qaida plot

When the class of 2002 was about 10 years old, a truck bomb exploded beneath the World Trade Center, creating a 100-foot crater, killing six and injuring more than 1,000.

The goal of terrorist plotter Khalid Sheikh Mohammed – to topple the twin towers – was not achieved. Perpetrators with ties to Osama bin Laden were caught and convicted. But al-Qaida leaders did not give up.

As the century turned, a new plot was underway with Saudi hijackers who trained in Afghanistan, got funding out of Dubai, formed cells in Germany and convened meetings in Malaysia, Spain and the United Arab Emirates.

The men ranged in age from 20 to 28, though some of their photographs released by the FBI resembled yearbook photos.

By early 2000, according to a final report by the 9/11 Commission, prospective pilots were attending flight schools in Florida and Arizona and renting simulators as they learned to handle jetliners.

A year later, at a camp in Afghanistan, bin Laden selected members of the “muscle teams.” They took loyalty oaths to al-Qaida and made videos declaring their commitment to martyrdom. As part of specialized training in knife combat, they butchered a camel and a sheep.

That May, as students in East Moline were ending their junior year, bin Laden met with underling Ramzi Binalshibh at Compound Six near Kandahar, Afghanistan. He instructed the 9/11 planner to give hijacking chief Mohamed Atta a list of targets: the White House, World Trade Center, U.S. Capitol and Pentagon – the White House being most important.

U.S. intelligence agencies picked up whispers of a new al-Qaida conspiracy against the homeland, but they had no details.

In June, an epic World War II film, “Pearl Harbor,” flopped at the box office. Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh was executed for carrying out what was then the deadliest terrorist attack on U.S. soil.

Summer vacation

In East Moline, summer vacation was in full swing. Teenagers cruised the Avenue of the Cities, worked, partied, fell in and out of love, attended camps for band, sports and cheer.

Fotos, the youngest of three kids born to Greek immigrants, was “just walking through life.” He’d lost at the state wrestling meet three years in a row. With a scholarship lined up at the University of Illinois, he had no intention of failing again. He spent the summer training on the mat and working at his family’s diner, The Coffee Break, in Rock Island.

When Hughes met with guidance counselors near the end of junior year, they told him college is tough and a high percentage of those who enroll wind up dropping out. Planning to become a cop, he started thinking about the military instead, perhaps as a military police officer.

A Marine Corps recruiter showed up at school. Hughes vividly recalls the image: trim and confident in dress blues and shiny shoes.

“I liked him,” he says. “I liked what he had to say. I liked his uniform, and maybe they’d give me one, too.”

Hughes enlisted, his start date delayed until after graduation. That summer, he worked at Osco, sweated through football practices and volunteered in the police explorer program.

He and his girlfriend started wearing T-shirts with Marine Corps insignia.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

Abney worked through the summer at Whitey’s Ice Cream parlor, babysat her siblings, organized a yard sale for school and drew up plans for homecoming.

Freeman worked at a youth sports camp, played soccer, hung out with his girlfriend.

‘Blinking red’

In mid-July, Binalshibh and Atta met in Spain to make final plans. Two planes would hit the twin towers, and one would go for the Pentagon. The White House was more difficult. They settled on the Capitol as a third target.

Binalshibh gave Atta bracelets and necklaces for the hijackers, telling him that they should be bathed and nicely dressed to resemble rich Saudis and draw less suspicion.

By then, threat levels had risen, and intelligence agencies warned that a potentially “spectacular” suicide attack against the homeland was imminent. On July 10, an FBI agent in Phoenix advised headquarters that militant Islamists with ties to bin Laden were attending U.S. flight schools and might be plotting an air attack. His memo was buried.

Al-Qaida pilots practiced in small planes over New York and Washington and took commercial flights on surveillance missions. Other teams were flown to Florida, Virginia, California and New Jersey. They rented apartments, purchased box-cutters, worked out at gyms, bided time.

By the end of July, CIA Director George Tenet later told the 9/11 Commission, America’s terrorism warning system was “blinking red.” U.S. citizens – office workers in the World Trade Center, soldiers at the Pentagon and students in the Quad Cities – were oblivious.

On Aug. 6, President Bush received his 36th intelligence advisory about an al-Qaida plot. It was titled, “Bin Laden Determined to Strike the U.S.” After that, threat warnings went silent, a calm before the storm.

As classes started Aug. 14 at United Township High, hijackers began to book suicide flights.

Best-laid plans of students and terrorists

In a house built by her grandfather, alongside rail tracks that run by a John Deere factory, Abney pulls out the memorabilia: homecoming photographs, a graduation cap, programs.

The to-do list in her calendar for the second week of September 2001: balloting for king and queen, flatbed trucks to haul parade floats, dance decorations in the gym, pep rally, rehearsal for the royal court.

“That was kind of my Super Bowl week,” Abney says, laughing.

Other students were settling into classes and extracurriculars, buying dresses and corsages.

Hughes was tabbed to perform at a spirit assembly as school mascot Pete the Panther, and he needed to develop a skit. Walters was cheerleading, in homecoming court, doing student government.

On Sept. 9, as the Dispatch-Argus ran a news story lamenting low PTA membership in Quad Cities schools, al-Qaida teams staged near airports in New Jersey, Virginia and Massachusetts.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

“The plan that started with a proposal by KSM in 1996 had evolved to overcome numerous obstacles,” the 9/11 Commission report noted. “Now, 19 men waited in nondescript hotel rooms to board four flights.”

In Boston, Atta and fellow hijacker Abdul Aziz al Omari ordered pizza for dinner.

At United Township High’s gym that night, school officials had issued a ban on moshing. But as a band performed the controversial song “Cop Killer,” its lead singer started bouncing and swirling with spectators.

Off-duty officers swept in and a melee ensued. Kids were cuffed and hauled to the police station, followed by protesting students who demanded police “free our friends.”

The incident earned a couple paragraphs in the Dispatch-Argus and might have been the talk of school on Sept. 11.

‘Are you ready to go to war?’

The students don’t remember getting up the morning that hijackers made it through security checks and boarded airplanes.

At 7:46 CT, just before classes began, American Airlines Flight 11 out of Boston plunged into the World Trade Center’s north tower, its nearly 20,000 gallons of fuel erupting in a fireball.

Seventeen minutes later, as news cameras focused on the skyscrapers, United Airlines Flight 175 hit the south tower.

At 8:37, American Airlines Flight 77 out of Washington swept into the Pentagon after circling the nation’s capital.

About 20 minutes later, after passengers aboard United Airlines Flight 93 fought with hijackers, the plane crashed into a Pennsylvania field, rather than Congress or the White House.

In East Moline, recollections are remarkably similar.

Fotos was in a government class taught by Mr. Johnson, the wrestling coach. Someone rolled a big-box TV into the room. News commentators were “playing guessing games,” speculating about the first aircraft when a second one struck.

“Everybody knew,” Fotos recalls. “A few people screamed. … I looked at my teacher, and I could see the shock on his face.”

Hughes usually arrived at school around 7:45, looking for someone to “help me” with homework, he says, using his hands to frame the quote marks.

He walked into a video production classroom and thought classmates were watching scenes from the movie “Die Hard.” But the scenes were the same when they switched the channel. Then the second jetliner hit the towers.

Hughes recalls a collective realization: “The country’s under attack.”

A classmate, aware of Hughes’ Marine Corps commitment, caught him in the corridor, asking, “Are you ready to go to war, Hughes?” He doesn’t recall what he said, just that he adopted the football mindset he used before a big game: “We’re going to hand them their butts.”

A teacher in tears came to Abney’s western civilization class, and Mr. Schmidt let the students out.

“I can still remember standing down by the library and the hallway completely filled with students watching TVs when the second plane hit,” Abney says. “There was just this collective gasp, and then a lot of crying.”

Abney says she didn’t break down. It was homecoming week and a student council president had decisions to make. “I remember kind of putting up my armor,” she says.

Within minutes, Abney was in a meeting with the principal, superintendent and senior class president. There was talk of canceling everything, she recalls, but they thought that would have given the terrorists a victory and wrecked senior year. “It’s our time. Don’t let them bring us down,” she says they decided. “But we were also really scared.”

There was no float-building that afternoon. The annual bonfire was canceled. Everything else was up in the air. Abney headed home to look after her little sister, and pent-up emotions poured out. “I’m bawling, and I’m telling her, ‘Rhiannon, do you understand the severity of what’s happened?’”

Abney feared her boyfriend, who had graduated two years earlier, might get drafted. Kids didn’t have cellphones then, so she couldn’t text. She found him sitting on the front stoop at his house, waiting. She rushed up and threw her arms around him, crying.

“He was like, ‘I’ll go. I’ll fight for my country.’ And I was like, ‘Noooo.’”

The Quad Cities nuclear power plant went on alert. Rock Island Arsenal beefed up security and shut down. Churches filled. Blood banks overflowed. National Guard units were put on standby.

Even more than 900 miles from ground zero, life changed.

“From that day, I’ve kind of been stuck to the news and what’s going on,” Fotos says. “Worrying about a bomb dropping on your head, you know – we’d never had these kinds of fears.”

‘America is under attack’

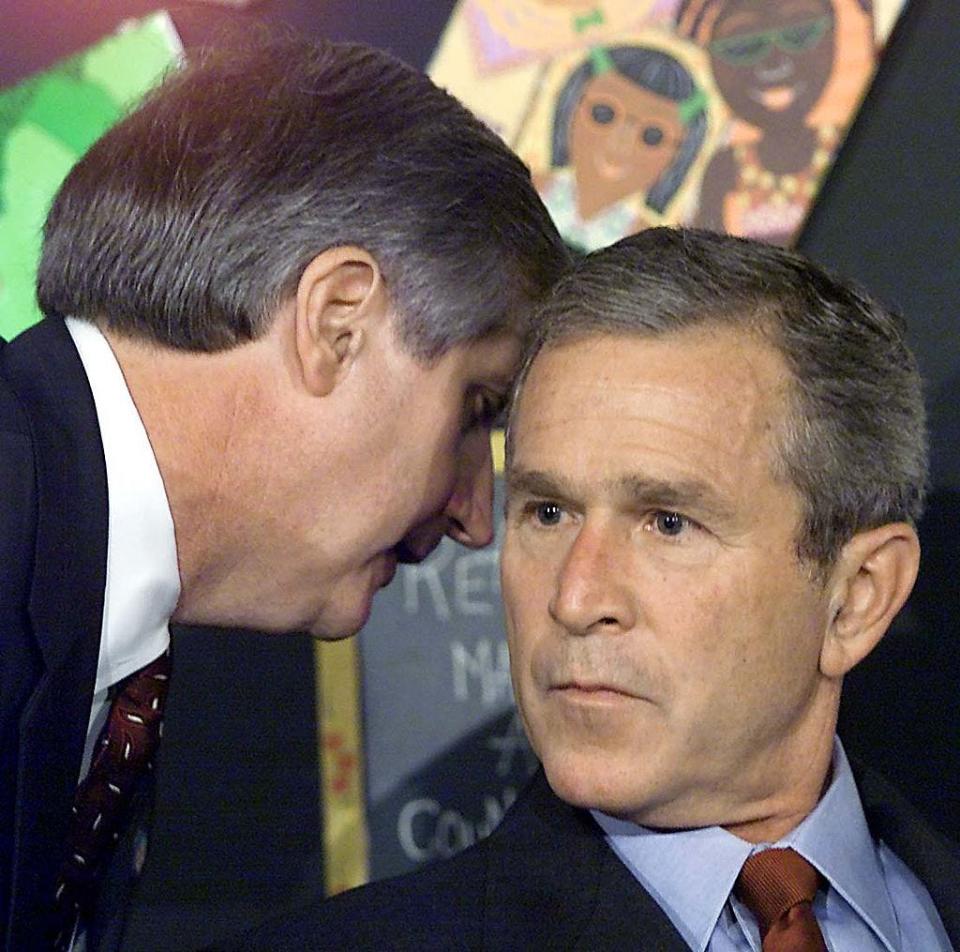

Bush was reading “The Pet Goat” to children at a Florida elementary school when an aide whispered in his ear, “America is under attack.”

Within minutes, Air Force One was wheels up, destination undecided, trying to protect the president. He jetted to a Louisiana military base, then one in Nebraska, uncertain of the threat or what was safe.

Finally, in the afternoon, Bush directed the pilot to head for the nation’s capital.

United Township High School superintendent Jay Morrow, then a football coach, was on the practice field with his team, starting warmups.

He recalls a cloudless sky, eerily empty and silent because all aircraft in the USA had been grounded.

Almost all, that is.

To the southwest, Air Force One appeared like a vision, a fighter jet at each wing, zooming over the Quad Cities. “We all kind of just stood there and looked at it,” Morris recalls. “I tell that story every year around Sept. 11, and my kids just roll their eyes.”

Homecoming week

As first responders dug through the carnage at ground zero and federal agents swept America for suspects, homecoming festivities proceeded in East Moline, with an accent on patriotism.

Walters remembers wearing red, white and blue ribbons during the Friday morning assembly. She had to switch from her uniform to her gown and back because the cheerleading team performed before and after the royal court was introduced.

“There were so many outfit changes for homecoming, and in my mind, that was the important thing – not that a few days earlier, 9/11 happened,” she recalls. “Now, I feel – I don’t know if ashamed is the right word – but you’re a senior in high school. Maybe selfish.”

Hughes’ skit included a gag with a pro wrestling championship belt. He dabbed the eyes of a teacher who was about to retire and lifted off Pete the Panther’s head. His football teammates went nuts.

The homecoming parade down Archer Drive, a tradition in East Moline, had no floats, but it did have the marching band. A fire truck was loaded with cheerleaders. Convertibles carried the royal court.

Parents and children lined the route, waving flags and cheering.

That night at Soule Bowl stadium, the Panthers beat the hapless Galesburg Silver Streaks, 35-7. Band music echoed through town. The king and queen were announced at halftime.

Saturday evening, the cafeteria was decked out for dancing. Walters wore a white gown; Abney's was hunter green. Who fell in love and which couple broke up will remain secret.

Abney recalls that smiles and laughter were subdued all week. “We were seniors,” she says. “This was our year. But then you felt guilty about having fun with life when so many had lost theirs.”

Abney recalls sitting in her room late at night after the duties and pageantry, recording a television tribute to the 9/11 victims and first responders, breaking into tears.

After the crash

All told, 2,977 died, and about 25,000 people were injured on 9/11; casualties came from 78 nations.

In the immediate aftermath, stock markets and airlines shut down. Church attendance and flag sales soared. Gas stations gouged consumers. National Guard units went on standby.

John Deere supplied tractors, excavators and other heavy equipment for rescue work at the Pentagon and World Trade Center.

An airline pilot, forced to divert and land at Quad Cities International Airport, took the passengers out to a movie. One, making the best of things in Moline, joked, "There’s about four hotels, a McDonald’s and a truck stop. … We’re gonna play putt-putt golf and just wait.”

Longer term, security laws and protocols were rewritten. Anti-Muslim hate crimes and discrimination soared. The nation’s economy, already dipping, went into a temporary nosedive.

Three months after the towers fell, 72% of Americans surveyed said 9/11 was more serious than the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, which pushed the nation into World War II.

Two decades later, aftershocks reverberate across America.

Operation Enduring Freedom began Oct. 7, 2001, when the United States invaded Afghanistan, ousting the Taliban, who supported and sheltered al-Qaida, within two months.

Much of the firepower for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq was produced at Rock Island, where students' family members worked, and where some members of the Class of 2002 are employed.

Bin Laden was tracked down and killed by U.S. forces in 2011. Mohammed, the blind sheikh and accused plotter of the 9/11 attacks, was captured in 2003. After 17 years of imprisonment and interrogations at Guantanamo Bay, he still has not been tried.

Last month, after nearly 171,000 military and civilian deaths on all sides and trillions of dollars spent by the federal government, the United States extricated itself from the longest military action in its history. The Taliban immediately took over Afghanistan.

A lawsuit filed by hundreds of 9/11 victims and family members, accusing the Saudi government of complicity in the attacks, continues in federal court. Many of the filings are sealed from public view.

In a world where each human is said to be linked within six degrees, 9/11 left few untouched, no matter who or where. Democracy, foreign policy and daily lives changed in ways we may never fathom.

Even in East Moline.

A family of Marines

In 2004, a Humvee flipped during military training in San Diego.

Amanda Walters had just finished finals at Black Hawk College, the Quad Cities community college, that day. Around midnight, her mom answered a knock at the door. Two Marines on the porch asked, “Are you the mother of Sgt. Matthew Adams?”

Walters' older brother, 27 and married with two children, had been killed preparing to deploy to Iraq with his reserve unit.

Walters says she lost her protector, the glue to her family, and with him a part of herself. The bubbly cheerleader personality submerged after that day. To block pain, she had to suppress joy.

If not for 9/11, “maybe he would still be here,” she says, crying softly. “I looked up to him so much. I just kind of shut down after Matt died.”

The Weapons Company sent two Marines home with the body. At the funeral, eight comrades carried the flag-draped casket to the front of the church. Over time, an entire Marine Corps unit became part of the Adams family.

They fought in Iraq, and several were killed, as Walters stayed in touch via phone calls and emails. They were at Amanda’s wedding, where a place was set for Sgt. Adams – empty except for a photograph and hat. The Marines attend a charity golf tournament each year in East Moline named for Sgt. Adams.

When one of the Marines got married in 2011 in New York, the Adams clan attended. Walters' husband, Robert – an ex-Marine who served in Afghanistan before becoming a firefighter – brought them to ground zero. The memorial had not been completed. They stood at the ruins, silent.

“I didn’t have my brother to turn to,” Walters recalls, “but I had all these Marines."

By then, she was teaching in Silvis. She says she didn’t fully comprehend 9/11 until she tried to explain it to eighth graders.

“You don’t realize the impact – how big it was – until you mature," she says. "Until you grow up.”

Protecting the president

Days after graduation, Andy Hughes started boot camp in San Diego, assigned to a unit destined for Hawaii. He promptly caught pneumonia.

The illness forced Hughes off schedule. When his unit shipped out to Kaneohe Bay, he sat idle in the barracks at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri.

When he enlisted, Hughes figured MPs would avoid combat because they do police work, but his unit wound up deploying to Iraq and took heavy casualties. Looking back, he wonders, "Can I say that I was fortunate?"

As Hughes waited at Fort Wood, officers from Helicopter Squadron One showed up seeking Marines to transport and protect choppers used by the president and other heads of state. After a background test and interview, Hughes recalls, “Somehow, I made the cut.”

It wasn’t as exciting as it sounds, Hughes says. He never flew with Bush, and he spent a lot of time standing guard in Washington. But there were trips around the world with smaller helicopters transported in cargo planes. He went to Paris for the 60th anniversary of D-Day. He was in Georgia for a G-8 summit and in Turkey for a visit with U.S. forces.

Sometimes, he’d wear the dress blues, just like that recruiter back in East Moline, and he'd salute the president as he disembarked.

He’s back in the Quad Cities, married with two small children, working as a cop.

Sept. 11 didn’t change his life trajectory, Hughes says, but it changed him. He tried to understand the hatred, wanting to ask the hijackers, “Where did it get you?”

In the den at his house, there’s a picture of Hughes and his dad with Bush. Before he was discharged from the Marines, he was invited for a photo op with the president. “I got so star-struck, and I don’t even know why,” Hughes recalls. When Bush asked his plans, Hughes said he was going to be a police officer. The president turned to his father and said, “You must be proud.”

‘Is this going to happen again?’

Dustin Freeman planned to go to the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign with his best friend, then get a law degree.

After a year at the state school, he came back to the Quad Cities and started business classes at St. Ambrose University. That led to an internship at John Deere and a career as a marketing manager for agricultural machinery.

Freeman's dad became police chief in Moline, and after retirement successfully ran for mayor. Freeman was his campaign manager.

Looking back, Freeman says he doesn't think 9/11 altered the direction of his life, but it transformed the world that his 4-year-old daughter faces.

She'll never be able to walk freely into the airport terminal in Moline, as he once did, watching planes take off and land. Or wander Rock Island Arsenal like he did as a boy, visiting grandparents' graves and climbing around on historic old tanks and rocket launchers.

He thinks back to that question that haunted everyone two decades ago: "Is this going to happen again?"

Coming full circle

Lambros Fotos won the state high school wrestling championship his senior year.

ACL injuries wiped out his collegiate and Olympic dreams, but he got degrees in history and education. He’s the wrestling coach at United Township High School, teaching for 16 years in the same classroom where he saw the al-Qaida attacks on TV.

The first week of the 2021 school year, Fotos puts a PowerPoint on the video screen and lays out his lesson plan for the students. To understand history, he tells them, you must first learn which sources to believe: Who is telling the truth about the Revolutionary War, the Nazi death camp at Auschwitz, the Vietnam War atrocities or 9/11?

The next segment of the course will study religions and their impact on history. The computer screen depicts images representing dominant world faiths, including the moon and star that symbolizes modern Islam.

A baby boy

Tess Abney's dream after high school included a foray into politics, so her classmates weren't totally off the mark when they said she was most likely to become U.S. president.

On Feb. 6, 2002, after a routine medical checkup, a doctor told her she was pregnant. “I was in shock,” she recalls. “I had to go tell my mom, and then I had to tell Dusty (her boyfriend). … I remember I was terrified bringing a baby into the world with everything that was going on.”

Abney was embarrassed, so she kept it secret until a few months later, when she completed a questionnaire on stress as a class assignment. One question asked about pregnancy. When she turned the paper in, Abney says, her teacher looked at it and blurted, “’Tess, you checked pregnant?’ And everyone gasped.”

She and Dusty got married. They have three kids.

“I know I changed as a person” because of 9/11, Abney says, “but I don’t know what I would have been without it. I think that security blanket was ripped out from beneath us. We realized … we were not untouchable.”

The baby born in 2002, Payton, graduated with the Class of 2021, his senior year obliterated by COVID-19. Schools shut down. A four-sport athlete had no games, homecoming, prom or social life. It was another generation-defining event.

At the kitchen table in her mom's house, Abney studies an old high school picture showing her and other students draped over one another. The pandemic is far worse than 9/11, she allows, more deadly and pernicious.

“I don’t know if it’ll ever be that way again,” she says, putting down the photo. “We’ll find out together.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Remembering the impact of 9/11: A defining moment for class of 2002