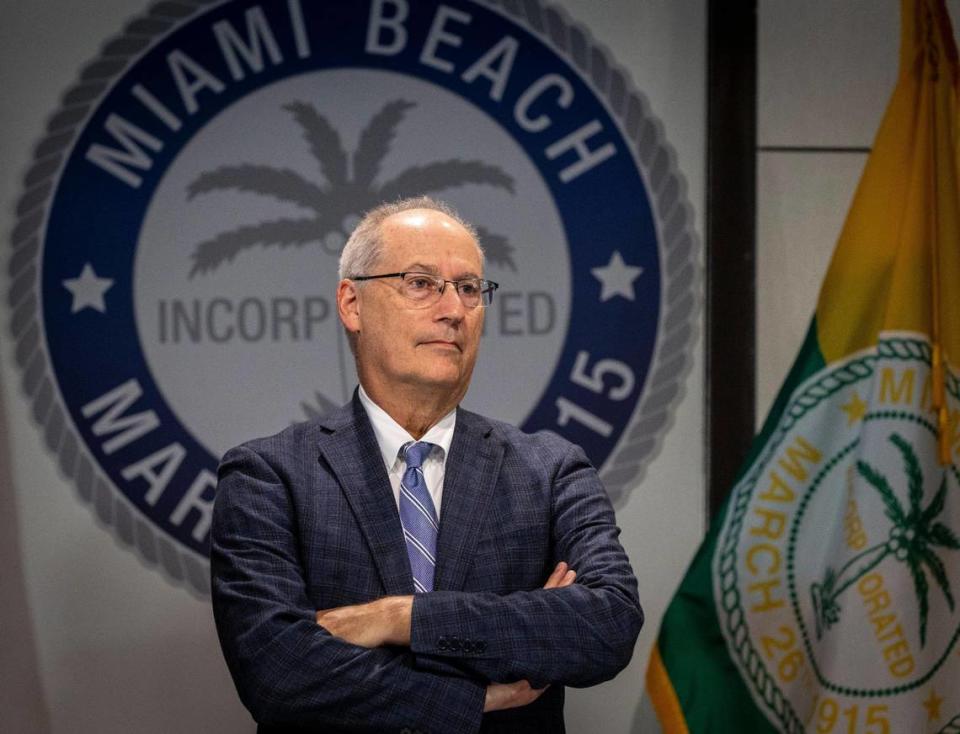

Mayor Dan Gelber led Miami Beach through an ongoing identity crisis. What’s his legacy?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In October 2021, Miami Beach Mayor Dan Gelber held a press conference in Lummus Park to promote a non-binding ballot measure on rolling back last call for liquor sales on Ocean Drive from 5 a.m. to 2 a.m.

Behind him, scores of protesters representing local bars and nightclubs held signs, chanted and booed, trying to drown out the mayor. Gelber spoke loudly but calmly into a collection of microphones.

“Welcome to Ocean Drive,” he said with a smile. “If you have any wonder about why there is disorder in our community, it’s behind me.”

In his six years as mayor of South Florida’s premier tourist destination, Gelber, 63, brought a steady hand and quick wit that he utilized to try to build consensus around the direction of a city in transition — often in the face of backlash from residents and colleagues who weren’t shy about telling him why they believed he was wrong.

Core to Gelber’s vision was reshaping the city’s identity, particularly in South Beach, from a late-night party town that had become unpopular among many residents, to a cultural destination that would attract older, more tranquil crowds.

On some fronts he succeeded. Gelber spearheaded passage of two large general obligation bonds approved by referendums in 2018 and 2022, under which residents agreed to raise their own tax bills to authorize dozens of capital projects totaling almost $600 million for parks, infrastructure, public safety, arts and culture.

As a result, green spaces citywide were revamped, new parks broke ground and a beachwalk running the length of the city was completed. Many of the projects are ongoing and will be realized in the coming years, including $159 million to upgrade the city’s arts and culture facilities.

“There’s a huge amount of investment now that our voters have approved to make these critical upgrades, both to infrastructure and to arts and culture facilities,” said Daniel Ciraldo, a Miami Beach resident and executive director of the Miami Design Preservation League. “Those are areas of his legacy that he’ll probably be most remembered for.”

During his first term in office, Gelber, who was reelected twice before being term-limited, reformulated a proposal to build an 800-room hotel next to the city’s convention center that voters had previously rejected. Residents approved it in 2018 and construction of that hotel, the Grand Hyatt, is now underway.

Gelber also campaigned on instituting an independent inspector general’s office to prevent fraud and waste on the heels of several corruption scandals. Voters overwhelmingly supported the move, and the office was established in 2019.

In other ways, progress was tough to come by.

Resiliency efforts to limit flooding due to sea-level rise, including the aggressive road-raising plans that defined the tenure of Gelber’s predecessor Philip Levine, stagnated as residents pushed back against the pace of the projects and associated hiccups for homeowners.

Voters approved the November 2021 straw poll calling for a 2 a.m. last call for alcohol, but the city faced defeats in court, and Gelber was unable to achieve consensus on a divided City Commission to implement it in the South Beach entertainment district. Instead, new 2 a.m. liquor curfews were limited to more residential neighborhoods like South of Fifth, leading to the closure of Story nightclub.

Meanwhile, even as data showed crime rates ticked down, and the city beefed up its roster of police officers and park rangers, many residents said they didn’t feel safe in South Beach — a feeling made worse by high-profile incidents of violence and deadly shootings on jam-packed Ocean Drive during spring break.

Gelber and other city officials took heat from locals for being unable to quell the spring break disorder and from Black community leaders for aggressive police tactics. In 2020, when the head of the local NAACP chapter criticized those tactics as racist, Gelber rushed to the police department’s defense, writing in an op-ed in the Miami Herald that “the notion that we are somehow ‘targeting’ people is ludicrous.”

In an interview last week, Gelber said the city has “tried everything” to change spring break.

“We tried not doing activations. We tried activations,” he said, referring to city-planned programming. “We closed things down. We opened things. The bottom line is, people are coming here.”

A vision plan to overhaul the design of Ocean Drive and nearby Washington Avenue and Collins Avenue — an area rebranded by Gelber as the Art Deco Cultural District — has been slow to get off the ground, although the proposal was accepted by the City Commission last year and there is bond funding allocated to execute it.

Gelber said law enforcement measures can only go so far in changing the area. And he said making the vision plan a reality could take 5 to 10 years and require more incentives for developers to convert properties into residential or office uses.

“Until it becomes a true, mixed-use cultural district with residents and businesses and restaurants and bars — until it’s live-work-play rather than play-play-play — we’re not going to be able to arrest our way out of it,” he said.

After 16 years in public office — including a decade in the Florida Legislature — Gelber says he’s not sure what’s next.

“I’ll wait to find something that intrigues me,” he said.

Leading through COVID

Gelber had all the experience he needed for the mayor’s role. He grew up in Miami Beach, and his father, Seymour, was a retired judge and the mayor of the city for six years in the 1990s.

Before becoming mayor, Gelber had served as a federal prosecutor, the Democratic minority leader of the Florida House of Representatives and a state senator. He made an unsuccessful run for Florida attorney general in 2010. He is also a partner at a private law firm.

After Gelber was elected in 2017, Seymour Gelber swore his son into office at the age of 98. Gelber was flanked during the ceremony by his wife, federal prosecutor Joan Silverstein, and two of their three children.

“The two of them are a lot alike,” said Michele Burger, the chief of staff under both Gelber mayors. “Seymour also was extremely intense. Seymour was probably more to the point. He was not as patient as Dan is.”

The mayor of Miami Beach runs City Commission meetings and votes on policy and budget matters, while a city manager oversees day-to-day operations.

When the COVID pandemic hit in 2020, Gelber quickly became a leader and a go-to voice in the media among local mayors preaching caution and a data-based approach to limiting public gatherings, even as the closures hurt Miami Beach’s booming hospitality sector.

He released frequent videos providing updates on the situation (some of which featured celebrities, like DJ Khaled and Gloria Estefan, encouraging people to follow safety guidelines) and sent a series of letters to Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis blasting him for taking what Gelber saw as an irresponsible, politicized approach to the crisis.

“I think that’s probably what I’m proudest of,” Gelber said of the city’s handling of COVID. “The performance of our city, I think, was extraordinary.”

Burger said the period exemplified Gelber’s leadership approach as a strong orator and a “convener” who leaned on experts for advice.

“Let’s bring everyone who has something to do with this subject matter into a room,” Burger said of Gelber’s outlook. “That’s a rare approach.”

Post-pandemic boom

As tourism began anew and people flocked to Florida, Miami Beach saw record-high resort tax revenue that put the city in a healthy economic position with a large pool of reserves and a budget nearing $1 billion. Major events like Art Basel returned and new ones sprung up, like the Aspen Ideas Climate conference that Gelber helped court.

But that success also came with consequences for residents as housing costs soared, making it increasingly difficult for working-class people to live in even the city’s more attainable neighborhoods.

Despite lofty goals, Miami Beach added little affordable housing during Gelber’s term. Gelber pushed for more “workforce” housing geared toward the middle class, including a development in the Collins Park neighborhood to provide 80 residential units and dormitory housing for Miami City Ballet dancers.

The return of tourism after pandemic closures also meant the worsening of traffic. During his State of the City address this past January, Gelber stood in front of a slide that read simply: “Traffic is Bad.”

Gelber and his colleagues sought to make improvements by working with the county and state to synchronize traffic lights, add dedicated officers to direct traffic flow and build several new bike lanes. But on larger-scale transit projects to connect the city to downtown Miami across Biscayne Bay, Miami Beach has been a dissenting voice.

Gelber, a longtime anti-gambling advocate, was the first elected official to publicly raise concerns in 2019 about a proposal by casino giant Genting to build a monorail between Miami Beach and downtown Miami.

When that plan was scrapped due to cost concerns and a Metromover extension was proposed in its place late last year, Gelber was initially supportive. But he and his colleagues have since demurred, choosing not to endorse the idea amid concerns from condo owners in the South of Fifth neighborhood.

“I’m skeptical,” Gelber said last week. A “Baylink” to the mainland is necessary, he said, but “you can’t just do anything. You have to do the right thing.”

Matthew Gultanoff, who founded the advocacy group Better Streets Miami Beach, said he believes Gelber didn’t do enough to address traffic and mobility issues while in office.

“We’re reaping those failures,” Gultanoff said. “The city has the resources to tackle the problems. It just has to be a priority.”

Rifts over development

Some Miami Beach residents have pointed to the construction of new towers under Gelber’s watch as a potential factor exacerbating traffic gridlock.

But the city’s population decreased over the past decade, according to U.S. Census data, and much of the new development has consisted of low-density, luxury condos.

On the campaign trail in recent months, several candidates pointed to Five Park, a more than 500-foot tall tower rising above the gateway to South Beach at Fifth Street and Alton Road, as an example of the type of eyesore they would oppose in office. Once finished, it will be the tallest building in the city.

Gelber has defended the project as an example of how to negotiate with developers. Rather than an original proposal for more units in a shorter building spanning multiple blocks, the city later approved a taller, less dense version tied to construction of a three-acre public park, Canopy Park, by developers David Martin and Russell Galbut.

“Would you prefer a tall building with a park with about 200 units of mostly absentee owners, or a wall of smaller units with no park?” Gelber said last week. “You have to make choices, and there’s not a third choice sometimes.”

Gelber saw resistance from voters on some development efforts, such as a proposal last year to have Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross and renowned architect Frank Gehry team up on a condo and hotel at the site of the demolished Deauville Beach Resort in the North Beach neighborhood. Despite Ross pouring nearly $2 million into a referendum to exceed current building-size regulations, voters shot it down.

Commissioner Kristen Rosen Gonzalez, who positioned herself as an opposition leader to Gelber, fought against the Deauville plan and was a frequent critic of the mayor’s development approach.

“Every time you see a crane, you can thank Mayor Dan Gelber,” Rosen Gonzalez told the Herald. “He likes to say it’s all parks, but there’s a tower attached to those parks.”

Neisen Kasdin, a former Miami Beach mayor who now represents developers as an attorney, said he believes criticism of development during Gelber’s tenure distorts the reality.

“It’s just a myth that there’s overdevelopment,” he said. “It’s the opposite. The city has very little development.”

Ciraldo, of the Miami Design Preservation League, said despite the fight over the Deauville, he saw Gelber as an advocate for the city’s Art Deco history. He pointed to Gelber’s pushback on proposed state legislation earlier this year that targeted local control of historic preservation.

“His administration was all very much there to support the preservation of our historic districts,” Ciraldo said. “That’s something that I’m grateful for.”

A parting gift

Despite a mostly diplomatic approach as mayor, Gelber wasn’t afraid to engage in high-profile fights and rib his political enemies.

In a recent spat with the owners of the Clevelander South Beach, Gelber denounced their plans to convert the popular hotel and bar into an 18-story residential tower and cracked jokes about their claim that Gelber had made “xenophobic” remarks about the Canadian owners.

Last week, as a parting gift to his rival Rosen Gonzalez, Gelber left a framed ticket in her office from a 2021 turkey drive that sparked a political fracas known as “Turkey Gate.”

Rosen Gonzalez had flagged concerns at the time about a proposal by Gelber to extend early voting so that the extra day of voting coincided with an annual Thanksgiving food drive near a polling site. An inspector general report later cleared Gelber and suggested Rosen Gonzalez may have improperly campaigned at the event.

On the ticket, Gelber wrote: “Please don’t forget to vote!!!”

Rosen Gonzalez said she wasn’t amused.

“He left me a final slap in the face,” she told the Herald.

Gelber said it wasn’t so serious.

“I thought she would appreciate that,” he said. “I’m surprised she didn’t find humor in it.”