How MCC failed cricket

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

At 10.55am on Wednesday, a bell will ring in the Lord’s pavilion to start England’s first Test against South Africa. The bell-ringer will be told this is a tradition of Marylebone Cricket Club and therefore a great honour. In fact, for the first 200 years and more of the club’s existence, it was a groundstaff lad that rang it.

Creating faux traditions — MCC turned its bell-ringing into a ceremony in 2007 — is one way for old, fading institutions to re-create themselves and present an image of modern relevance. The International Cricket Council have just bought into the club’s strategy: the World Test Championship finals of 2023 and 2025 will be staged at Lord’s, even though Melbourne has three times the crowd capacity, and Ahmedabad four.

Does MCC deserve such a large slice of cricket’s cake, which comes from staging two Test matches per summer and charging a three-figure sum for a decent seat? The club’s record from its foundation in 1787 until 1968, when it ceased to be the game’s governing body in England and Wales, is patchy at best. Lord’s was the first home of match-fixing; its pitches were deplorable and, in one tragic instance, fatal; the MCC Committee was accused of being a bastion of support for apartheid in South Africa, notably in the Basil D’Oliveira affair in 1968; and the portrait of Benjamin Aislabie, the first MCC secretary and one of Britain’s largest slave-owners, was displayed in the pavilion until two years ago.

So, to justify the title of Lord’s as “the home of cricket”, MCC has to be doing a pretty good job at administering the Laws — the club's last official function in the global game — but also at influencing the sport’s future for the better. For too long, and for all the good intentions of the current leadership, it can — and hereby will — be argued that MCC historically did more harm than good.

Fixing, and a fatality

MCC’s early records went up in smoke when the Lord’s pavilion burnt down in 1825: some may have seen it as divine retribution, like the termination of Sodom and Gomorrah, because Lord’s had become the home of match-fixing. Gambling was a major feature of Georgian and Regency society, and cricket emerged as a sport played between two teams, captained by nobility and gentry, for large stakes. Malpractice, however, went far deeper.

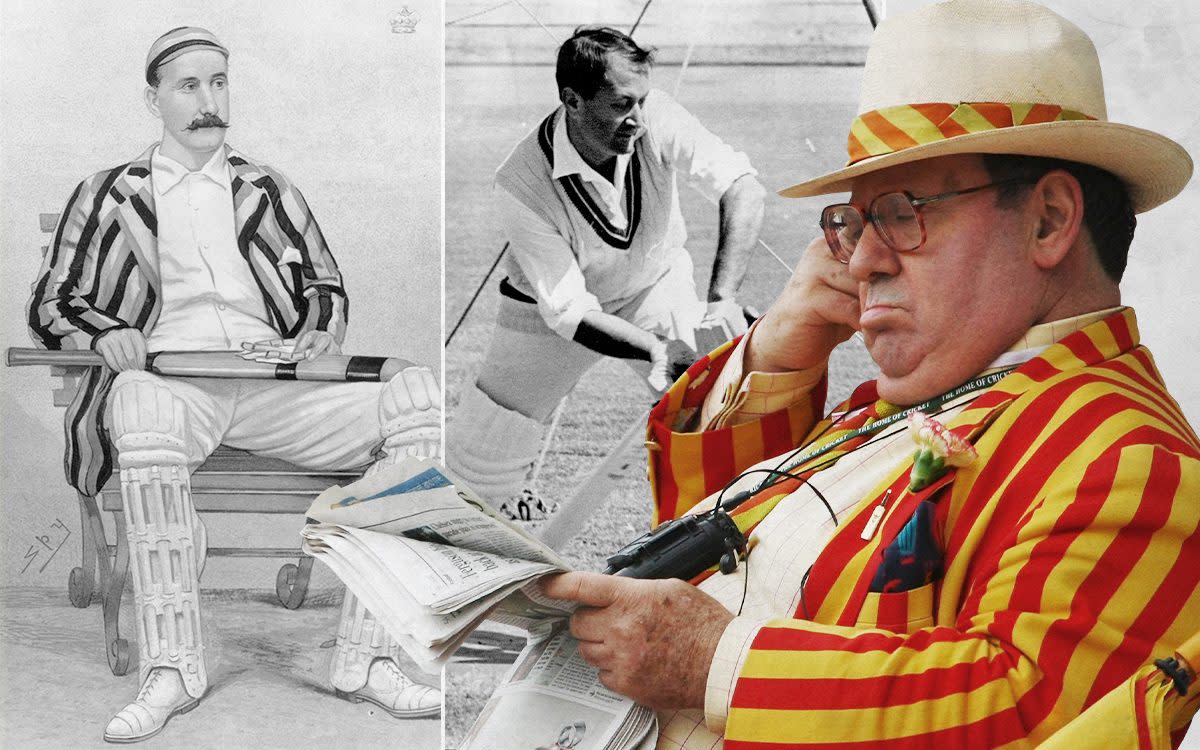

“Matches were bought and matches were sold,” recalled William Fennex, the batsman who introduced playing off the front foot. “Legs”, as messengers working for bookmakers were called, operated outside the pavilion that was to burn down. “The outcome might be seen in the deliberate missing of catches or bowling of long-hops,” GD Martineau wrote in They Made Cricket. The most notorious player and gambler was Lord Frederick Beauclerk, son of the Duke of St Albans, who admitted to making £600 per season out of betting on cricket matches, the equivalent of £60,000 today.

“Matters were brought to a head when two players who had been victims of this roguery fell out openly; their quarrel attracted a crowd, and they were brought into the pavilion at Lord’s, where revealing recriminations continued. The dirty linen was all brought out before a horrified committee, and the consequence was a general cleaning-up of the game,” Martineau concluded. But the cricketer who was banned for match-fixing in 1818 was William Lambert, the professional who had just become the first person to score a century in each innings of a match. Beauclerk went on to become MCC president.

Cricket required leadership, on a national scale, but MCC was in no fit state to supply it. Even the club’s official biographer, Sir Pelham Warner, conceded as much. He quoted Edward Rutter, who was elected to the MCC Committee along with CE Green, a future President, as saying: “We proceeded to sit in conclave with our elderly and reactionary fellow-members. At first we were distinctly ignored, and Charlie Green was so utterly disgusted with the supercilious manner in which he was received that he declared he would never serve on the Committee again.”

MCC could not even put its own house in order. The self-proclaimed leading cricket club in the world, did not employ a groundsman until September 1864, and then he was forbidden to use a new-fangled mowing-machine. Grass was left to grow, then flattened like hair combed over a bald patch.

In June 1870, George Summers paid the ultimate price while playing a three-day game for Nottinghamshire against MCC at Lord’s. Batting at number three in his first innings, Summers was bowled for 41 by a shooter delivered by the Derbyshire fast bowler John Platts. With this dismissal in mind, Summers presumably made a conscious effort to play well forward in his second innings. But the first ball, again from Platts, reared and hit him on the cheek-bone. According to Warner, “the ball pitched on a pebble which had worked up.”

Summers was carried from the field, unconscious. Three days later he died, aged 25. In a more litigious age, his family might have sued MCC; in 1870, they settled for the club paying for his gravestone.

The premier cricket ground in London north of the river came to be Prince’s, not Lord’s. Neither was named after nobility. It had been a Yorkshireman from Thirsk, Thomas Lord, who bought MCC’s first three grounds, all in the vicinity of Marylebone; and it was the brothers George and James Prince who bought land in Chelsea and made it a playground for the rich, offering tennis, badminton and skating as well as cricket in the 1870s. Prince’s had “one of the finest playing grounds in England,” according to Wisden. Middlesex CCC, faced with a choice between Lord’s and Prince’s, preferred to play at Prince’s.

MCC was finally forced to up its game, and its ground. Once the Prince brothers had sold their prime real estate for housing — it became Walton Street and Cadogan Square — the last games were played at Prince’s in 1878. Since 1877 Middlesex have been based at Lord’s and thereby filled up its fixture-list.

Losing grip of the laws

It can be argued that MCC blocked cricket’s evolution for decades. Bowling had originally been under-arm and MCC, in control of the Laws of Cricket from 1787, wanted it to stay that way. Round-arm bowling became widespread during the 1820s but it was not until 1835 that MCC sanctioned the new style, which naturally allowed more pace on the ball. Not until 1867 did MCC legalise bowling above the height of the shoulder, long after it had become common practice.

More recently, it was too slow to recognise that bats were changing the game and making it a more physical, even violent and dangerous sport. When the late John Woodcock, doyen of cricket journalists, was on the MCC cricket committee in the 1990s, he kept telling them to limit the thickness — not the width — of bats, but he said they would not listen. Not until 2017 was the bat limited to 67mm in thickness or depth.

Now the Laws committee are doing a fine job, under MCC Laws Manager Fraser Stewart. They made cricket more hygienic by banning saliva on the ball; and took the heat out of “Mankading” by removing it from the section on Unfair Play and making it a legitimate form of run-out.

Two proposals for their agenda. One is that MCC would do well to revert to the first Law which it introduced back in 1788, about the ball: “it cannot be changed during the game but by the consent of both parties.” This would save a lot of the time being wasted by fielding sides who want a ball that is harder or swings more.

Secondly, stop analysts off the field — where the umpires cannot police what is fair or unfair play — posting messages to the fielding side. The preamble in the Laws about the Spirit of Cricket is inadequate and needs to enshrine this basic principle: cricket is a game for the players on the field to play without external interference, so they think for themselves.

A coaching manual that ‘restricted kids for generations’

It takes an Aussie to tell it to you straight: “I think that the MCC coaching scheme is monstrous.”

Colin McCool, the writer, played 14 post-war Tests for Australia, and as a pro in Lancashire leagues, before representing Somerset from 1956 until 1960. He learned all about the English game, and loved county cricket, and when he returned home, he gave MCC both barrels. And with the benefit of hindsight we can see McCool was spot on. MCC made English cricket moribund in the 1950s, specifically from 1952 when the first two of many editions of the MCC Cricket Coaching Book were published.

“A system (ie the MCC coaching scheme) whereby people can be mass produced as coaches, and let loose upon the unsuspecting youngsters of the world waving slips of paper which qualify them to teach the game of cricket, is such nonsense that it would make you laugh. Except that it can do so much harm,” McCool wrote in Cricket is a Game.

“Every winter a flock of English players visit overseas countries teaching the doctrine of English coaching. They all carry the MCC’s advanced coaching certificate, which is a step or two in front of the one held by schoolteachers, youth leaders and the like but based on the same deadening principles.

“The basic aim of the MCC coaching scheme seems to be to teach batsmen to do everything except hit the ball… The basis of MCC coaching is the forward-lunge: left foot flung as far down the pitch as it will go, bat following limply behind and the right toe dug firmly into a hole an inch behind the crease. Circus clowns, adept at the splits, would make ideal batsmen under this scheme. ‘When in doubt, push out’. This is the catch-phrase that has knocked the art out of batting."

Here are serious allegations. And McCool substantiates them by giving the example of South Africa’s five-Test series in England in 1960 which “produced a brand of cricket as exhilarating as a glass of muddy water. Everyone moaned about the dullness of it all. But why? South Africa were merely exporting to England their own product, the type of cricket Englishmen have been playing, perfecting and teaching for years.”

The MCC coaching book was undoubtedly well-intentioned, and did insist that “to cramp boys with purely defensive technique… is the worst of coaching sins.” But that was not the consequence of what they preached. The coaches they trained preferred to focus on another edict: “By far the most important, and the most difficult, task of any coach in batting is to train the young batsman to play straight.”

In the hands of MCC trained coaches, it was not “see ball, hit ball.” It was “see ball, block ball.” The club asked Denis Compton, the freest of England batsmen before Kevin Pietersen, to pose for photographs in the book to illustrate the perfect grip and stance. But there was no mention or illustration of the sweep, which was Compton’s signature shot. The sweep did not involve the forward-lunge and playing straight.

In bowling too, “deadening principles” were applied by MCC coaches. “He [the bowler] must be able to command accuracy in length and direction. This accuracy is the very foundation of his craft.” Wiser coaches encourage bowlers to bowl as fast as possible or spin the ball as hard as they can. And thank heavens for West Indies and Pakistan, where, after independence, cricketers grew up without being coached at all.

England’s scoring-rates in Tests from the 1950s tell the dismal tale. This moribundity also permeated county cricket where scoring-rates and attendances slumped towards crisis-point. The domestic game was saved by the invention of limited-overs county cricket in 1962. It was the brain-child of Michael Turner, the secretary of cash-strapped Leicestershire, nothing to do with MCC.

State schools neglected and a star sidelined

When MCC celebrated their bicentenary in 1987, it was a grand occasion: Malcolm Marshall’s bowling, and Roger Harper’s running out of Graham Gooch, will linger in many a memory. Under the surface, however, what did MCC have to celebrate apart from their longevity as guardians of the sport for 200 years? In addition to the prestige of receiving an annual royal visit, that is, and the notoriety for having the world’s surliest gatemen.

Away in Preston, Lancashire, boys and girls to whom cricket was an alien language were growing up; and, as we can see in Andrew Flintoff’s BBC series, their children too have not the slightest connection to cricket.

Primarily, the loss of cricket to whole sections of society — especially those who have attended state schools in urban areas — is the fault of the ECB, for removing cricket from terrestrial television after 2005.

But it is also the legacy of MCC, the governing body of cricket in England and Wales until 1968, when the Test and County Cricket Board was set up. Even when the administration of the sport passed to the TCCB, however, the values did not change, because the chairman and vice-chairman of the new organisation were the president and treasurer of MCC.

By the end of the 1960s, not only was cricket being sidelined in state schools but MCC was embroiled in arguably its biggest scandal of the 20th Century: the exclusion of Basil d’Oliveira from England’s tour of South Africa in 1968-69. Tony Lewis in Double Century, which celebrated the club’s bicentenary, wrote that MCC’s “every decision reeked of political expediency.” It was not as if their committee was ill-informed: they had members such as Rev David Sheppard and Michael Brearley to tell them all about apartheid in South Africa.

All the while, MCC preached to the converted, sending teams to play various clubs and the fee-paying schools of England, as they do to this day. Their results against fee-paying schools are a reflection of the fact that it is men against boys. But why does MCC play so few state schools, who have to find £200 to pay for MCC’s lunches and teas, even if they have a playing field?

A corner is turned

It was not until the 1990s that the MCC began to put back more into cricket than it took out. It is doubtful whether Sarah Fane would have been warmly received by the MCC Committee of 1860, let alone appointed to a job, but if anybody personifies the good which the club now does it is she as the director of the MCC Foundation.

Fane had the good fortune of a basis on which to build. The MCC Foundation had begun by setting up hubs around the country to bring cricket to the unconverted. This was largely the inspiration of Roger Knight, the former Cambridge and Surrey captain. Today there are 74 hubs which cater for state-educated children, only, and free. Less than a fortnight ago, Lord’s — the main ground, not the Nursery — played host to two finals, between the Under-15 boys of Newcastle and Nottingham, and the Under-15 girls of Bolton and Guildford.

MCC has been able to direct more resources into the Foundation after ceasing their £600,000 annual sponsorship of six universities, which lasted from 2004 to 2020. The money that went into Cambridge, Cardiff, Durham, Leeds/Bradford, Loughborough and Oxford — essentially to pay the salaries of well-qualified coaches — has been re-directed to grassroots, and the university programme handed over to the ECB. It bore some fruit. Andrew Strauss, while at Durham, benefited from the insights of a former lefthanded England opening batsman in Graeme Fowler; and dozens of county players were better cricketers and people for the experience. But few would argue against the cash being of greater use further down the food chain.

Another platform on which Dr Fane built was the MCC’s existing relationship with Afghanistan. Just as MCC had given a helping hand to most countries before they acquired Test status, they played an Afghan team in Mumbai in March 2006, and were thoroughly trounced. But that was the point. Afghanistan, though the sport had never been staged in the country, already had some prodigiously talented cricketers raised in Peshawar and surrounding refugee camps. Hamid Hassan was soon to be as fast as any bowler in the world until his zeal crippled him, when leaping a fence and tripping while fielding; and Mohammad Nabi is still one of the leading T20 all-rounders.

After the debacle in Kabul last August, several hundred Afghans were billeted at a hotel in the Edgware Road and Fane offered them sanctuary once a week at Lord’s indoor school. Not just cricket but language classes, and Afghan food: a few tastes of normality.

Backed and accompanied by the CEO Guy Lavender, the MCC Foundation has supported the extraordinary Alsama project which helps Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

It offers boys and girls an all-round education, based on the completely novel pastime of cricket. I cannot possibly do better than quote what Fane wrote after they had visited, not only the more permanent refugee camps in Beirut, but the newer ones in the Bekaa Valley last freezing February.

“It is hard to know how people survive, stuck here, a forgotten people, who cannot progress or believe in a better future. Yet, once again, we are taken aback by what we find. For in these tents, the women strive to create homes out of nothing. They show us with pride their tent homes, the room where all the children sleep on makeshift beds, the tiny kitchens with windows cut through the canvas letting in some light, but also the freezing wind. And they smile and welcome us. These are the female cricket coaches, who are now earning money and keeping their families, carving a future from the void.”

Were they to meet Fane and her Foundation team, MCC committees of the past would no doubt go apoplectic. Which, in itself, must be a sure sign of progress.