McCurdy: Despite differences, King, Ali 'still brothers' who changed America

If someone were to travel back in time to the 1960s and tap anyone on the shoulder and whisper this news, no one would believe the message.

Within a generation, America will celebrate the life of Martin Luther King Jr. with a national holiday. And, oh yeah, Muhammad Ali — that guy so many of you still derisively call Cassius Clay — will die an old man as one of the most beloved figures in American and world history.

Crazy. Impossible. Absurd.

Be reflective. Be honest. For anyone who lived while these two men both walked the Earth at the same time, it's inconceivable to think that within decades, the memory of King and the life of Ali would be what it is today.

That both came from opposite ends of the struggle and ended in the same place in the world's conscience speaks to the character of each man.

King was the leader of the Civil Rights movement starting in the 1950s and continuing until his assassination in 1968. He preached about inclusion and integration, and he led protests and marches to highlight the injustices Black people endured in this country.

Ali was the outspoken heavyweight boxing champion of the world. He joined the Nation of Islam, changed his name to reflect his change in self and spoke of Black pride and power. He wasn't interested in desegregation, only true freedom.

"All I want is peace — peace for myself and peace for the world. I don't hate any man, black or white. I just want to live with my people. ," Ali is quoted as saying in a 1964 interview that Thomas Hauser collected in his definitive book, "Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times."

He continued: "I don't believe in forcing integration. I don't want to go where I'm not wanted."

That was the opposite of what King and his followers wanted. King's goal was to integrate all facets of life, be it schools, employment, transportation, housing, the government, the ballot box.

And that's where the two icons clashed.

"People are always telling me what a good example I could set for my people if I just wasn't a Muslim," Ali said. "I've heard over and over, how come I couldn't be like (previous great boxers) Joe Louis and Sugar Ray (Robinson). Well, they're gone now, and the Black man's condition is just the same, ain't it? We're all catching hell."

Ali refused to play a part in King's March of Washington, taking the lead of his friend and mentor Malcolm X.

"I had respect for Martin Luther King and all the other civil rights leaders, but I was taking a different road," Ali is quoted in Hauser's book.

King was rankled by Ali's sentiment, as Hayes Gardner of the Louisville Courier Journal wrote a year ago. King saw Ali as a loquacious young man with an important pulpit being the heavyweight champion of the world. Ali was a potential ally in the cause, but instead, King would get no help from the champ.

"When he joined the Black Muslims and started calling himself Cassius X, he became a champion of racial segregation, and that is what we are fighting against,” King said at a conference in Detroit, reported by the Associated Press at the time. “I think perhaps Cassius should spend more time proving his boxing skills and do less talking."

Yet through all the differences of opinion, the two were friendly toward one another in private. We know King sent Ali telegrams of congratulations early in his pro boxing career, and in the mid-1960s the two enjoyed phone conversations, which we've learned from FBI notes taken while wiretapping King.

In one conversation, noted in Hauser's book, Ali and King exchanged pleasantries; King congratulated Ali on his recent marriage; Ali invited King to an upcoming fight; Ali called King his brother and said "he's with him 100 percent, but can't take any chances, and that MLK should take care of himself ... and watch out for them whities."

Soon enough Ali and King publicly found a common cause — protesting the escalating war in Viet Nam.

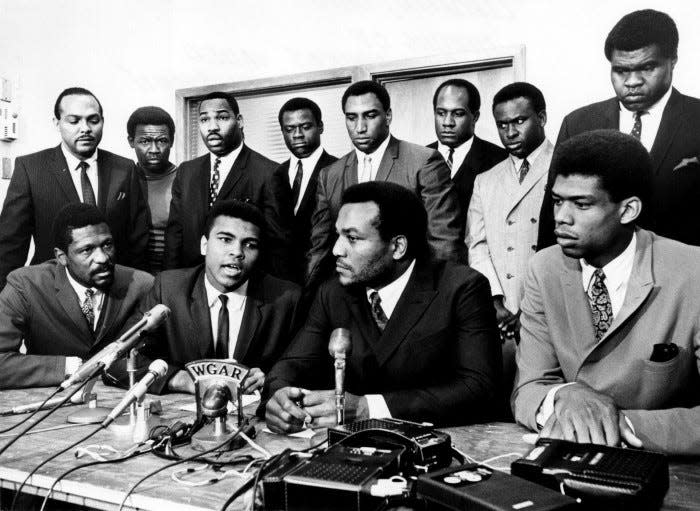

Ali refused induction into the Army via the draft and lost his career over it. King was also outspoken against the war, and in 1967, the two met face-to-face in a Louisville hotel.

Afterward, as Gardner reported last year, the two met with reporters who wondered what they spoke about.

"Nothing, just friends, just like (Nikita) Kruschev and (John F.) Kennedy and everybody," Ali said while making King laugh. “When the people, all of the politicians, all of the white racists come together, although they believe different, they think different, whites can come together and discuss the common cause, but whenever a few of us come together, the world is shook up."

Indeed the two shook up the world. In a 1966 Gallup Poll, 63 percent of Americans had an unfavorable opinion of King. If a similar poll was taken of Ali, it would have been worse.

Too many in America viewed them as Public Enemies No. 1 and 2.

“As Muhammad Ali has just said, we are all victims of the same system of oppression, and even though we may have different religious beliefs, this does not at all bring about a difference in terms of our concerns," King said after the Louisville meeting.

A year later King died from an assassin's bullet. Soon, public opinion of the war shifted. Ali won his court case regarding the draft and regained his career. In the 1970s, Ali drifted away from the Nation of Islam and remade his image, becoming a darling of pop culture.

By 1983, none other than President Ronald Reagan signed the King Holiday Bill into law, and Ali was finished with boxing, living on the world's stage as an advocate for the underprivileged and a promoter of peace.

More so, in a 2011 Gallup Poll, King was viewed favorably by 94 percent of Americans, while in 2016, Ali died a hero to the masses.

King and Ali weren't two men ahead of their times. Instead, they were two men who forced time and sentiment to catch up to them.

"Still brothers," Ali said with King standing next to him in Louisville. "Still brothers."

It was a remarkable friendship and a remarkable change of sentiment by everyone living in their time and since.

Rob McCurdy is the sports writer at the Marion Star and can be reached at rmccurdy@gannett.com, 419-610-0998, Twitter @McMotorsport and Instagram @rob_mccurdy_star.

This article originally appeared on Marion Star: McCurdy: King, Ali 'still brothers' who changed America