What It Means to Center “Healing Justice” in Wellness

I think the allure of wellness has a lot to do with agency; there’s a sense of empowerment in making decisions about our well-being when so much of life is beyond our control. When our world is rocked sideways, we can always turn inward, relying on our tried-and-true methods of self-care to take the edge off.

But we’ve all seen how a genuine desire to feel good and grounded can morph into a personalized pursuit of optimal well-being, devoid of connection from others, and ultimately ourselves. If we want to democratize wellness, we have to dismantle the obstacles that inhibit many of us from caring for ourselves and others, and reckon with systems that tout well-being as a luxury good instead of what it is: a fundamental birthright. What would it look like to shift our perception of wellness to include the collective?

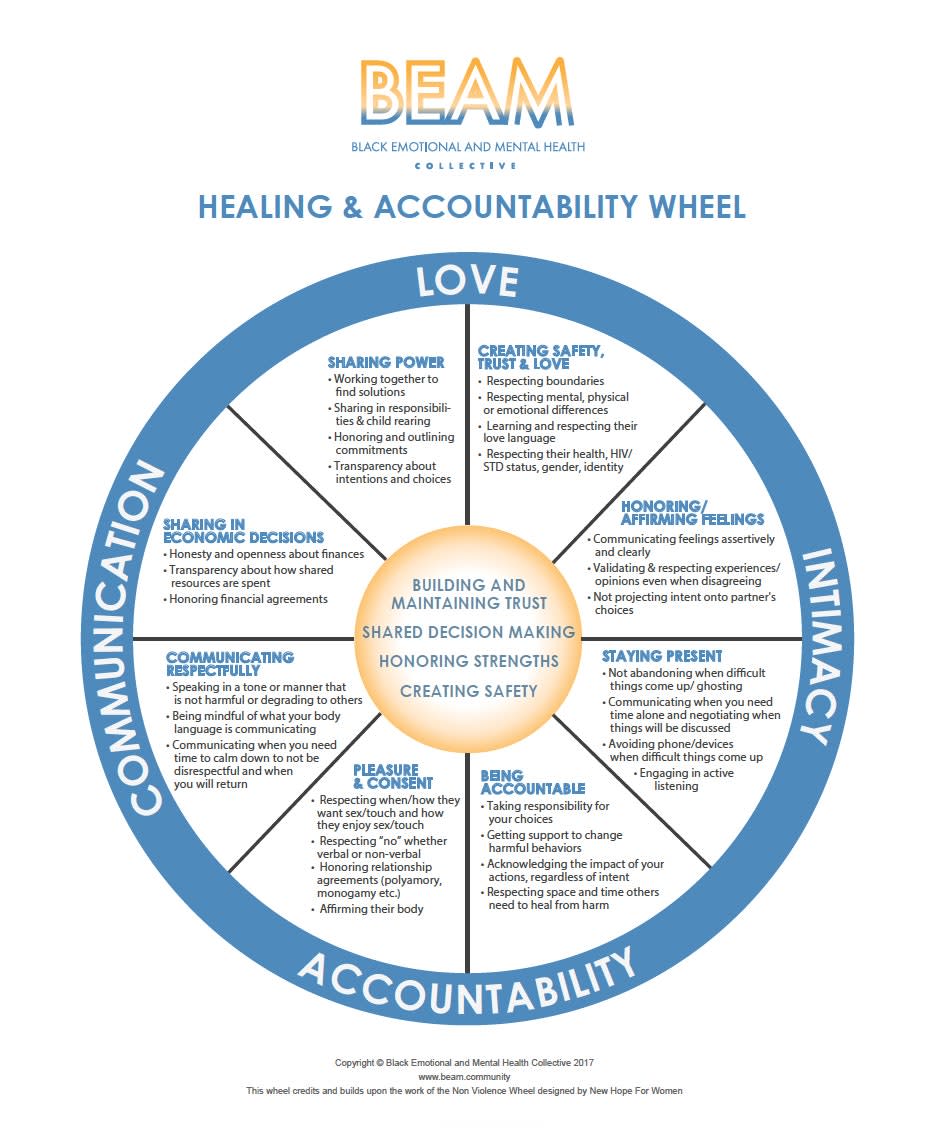

“Healing justice” is both a term and movement, first coined by the Atlanta-based Kindred Southern Healing Justice Collective in 2007, that aims to address widespread generational trauma from systemic violence and oppression by reviving ancestral healing practices and building new, more inclusive ones. The healing justice movement has since expanded to include a network of practitioners and organizations like the BEAM (Black Emotional and Mental Health) Collective, a group of activists, artists, educators, religious leaders, and lawyers, which offers everything from online workshops and panels, peer support training, therapy resources, and free tool kits and journaling prompts geared toward mental health education and outreach. I spoke to BEAM founder Yolo Akili Robinson about the legacy of the healing justice movement, reimagining wellness for the collective, and why we need more walks with friends—not more bath time—in the name of self-care.

How have you come to understand and implement healing justice in your work?

Healing justice comes out of the work of Black, Brown, and Indigenous queer, trans, and disabled folks who ushered in this naming of practices that our people have been doing for eons. That lineage includes people like Cara Page [a founding member of the Kindred Southern Healing Justice Collective], Prentis Hemphill [Healing Justice director of the Black Lives Matter movement], and Erica Woodland [founder of the National Queer and Trans Therapists of Color Network], and while I count myself among them, I want to make sure I name that before I talk about defining it. As a nonbinary person who often is projected as a man, that has meaning.

When I think about healing justice, I think about a couple of different things: I think about the transformation of our world, the systems, the institutions, the communities, as well as our relationships to ourselves. What would happen to our world if we understood that healing was deeply connected to the dismantling of racism, of transphobia, misogynoir, and ableism, and chose to center that? That’s what I think healing justice offers us: the unpacking of it all and engaging in that work. We started BEAM by imagining, building, and creating through that lens.

Is there a working definition of wellness that BEAM uses?

Oftentimes we’ll say we are working toward wellness, or we’re working to honor wellness. I think wellness can be amorphous and a little bit hard to pin down. Healing is not about this ableist vision of all of us showing up the same way every single day, right? It’s about cultivating our relationship to our emotional and psychological selves that fosters tenderness, liberation, and joy.

It’s about trying to move away from this idea of wellness as this state of perfect human, which historically, has been defined by white people. Taking a bubble bath isn’t necessarily healing justice, right? Healing justice is really about looking at the systems, legacy, intergenerational trauma—all these pieces where harm still lingers, and beginning to restore and heal that harm.

What are your thoughts on the word self-care and where it sits in healing justice work? Do we need a new word?

I’m not a big proponent of “self-care.” There’s not much that’s sustainable on our own, particularly when it comes to regulating our emotional lives and well-being. We need support. During quarantine, my best friends and I have been going for walks. That is a wellness practice. A big part of healing justice is unlearning the strategies rooted in capitalism and ableism and finding the practices in community with others that helps you to cultivate your wellness.

If we believe that we are not doing good work unless our bodies are to the point of exhaustion, the psychological and emotional consequences are high. Engaging with this from a healing justice perspective is beginning to really interrogate: How has my perception of productivity changed or distorted my relationship with my body? Do I have a relationship with my body? Boundaries are extremely difficult for many of us, because we have been taught that we don’t have a right to boundaries, or our bodies.

Wellness, as we’ve come to understand it, preys on us feeling separated from ourselves and the world. There is a hyper-focus on the individual, when in reality, there are so many external forces that can dictate our paths to healing.

Right. The thing I love about healing justice as a framework is it just really gives us language for how deeply embedded our ability to cultivate healing and wellness is impeded by systems of oppression. BEAM has an initiative called Black Masculinity (Re)Imagined, where we work with masculine folks and Black men to really begin to interrogate the link between what they learned about emotions and feelings as a young person, and all the messages telling them to sever, disconnect, repress, and deny their emotional selves. That is what creates isolation, depression, and anxiety for Black men and masculine folks, while also creating violence and death for Black women and queer trans folks. Too often it’s Black cis men who are killing Black trans women; in order for us to cultivate wellness and healing justice for Black men in this country, we must talk about transphobia and misogynoir because they’re so deeply rooted in toxic masculinity.

Emotional literacy is a big component of BEAM’s mission. How does your commitment to mental health literacy and healing translate into the care and resources you provide for the BEAM community?

We believe that our communities have the resources, whether they are internal or not, to heal—that we have a legacy of being healers. Oftentimes people focus on Black communities as communities of struggle, but we also have a legacy of resilience. And so what we try to do in our work is uplift those strategies that are beautiful and powerful, but also help refine some of the ones that haven’t been as useful.

One of the popular tools that we use is a feelings wheel. Black people have been told that our feelings are not valid or real. We have been pushed out of our feelings by white supremacy; that’s what our parents and guardians have internalized and what we’ve internalized. Our feelings are valuable forms of knowledge. Healing justice really says we must reimagine the world, and I think that’s the opportunity: thinking about how we reclaim our emotional selves, our inner compass, and inner voice.

Originally Appeared on Bon Appétit