Midterm ballot measure to decide if Oregon lawmakers will be punished for absences

This fall, Oregon lawmakers could get an attendance policy.

Ballot Measure 113, if approved by voters in the Nov. 8 election, would disqualify state lawmakers from holding office for the next term if they have 10 or more unexcused absences from the House or Senate.

Between 2019 and 2021, Oregon Republicans left the state Capitol several times to stop the Democratic majority from passing laws. Their absence prevented legislators from passing a bill to lower the state’s carbon emissions and forced the 2020 session to end days before the constitutional deadline, leaving dozens of issues unresolved.

If approved, Measure 113 could end a divisive political tactic that has grown increasingly popular. But it also could diminish the minority party’s power in the state Capitol.

Oregon needs quorum to take votes

State lawmakers pass new laws and write the state’s budget. While a simple majority is usually all that's needed for most new laws to pass, Oregon requires a higher share of lawmakers be present to take a vote.

In the House, 40 out of the 60 representatives have to be there, and in the Senate, 20 out of 30 senators.

That means that even with a strong majority in both chambers, at least one or more members of the minority party usually need to be in attendance for lawmakers to vote. Right now, Democrats hold 37 House seats and 18 Senate seats.

More on the midterm: Could Oregon Republicans win more seats this fall?

Republicans have coordinated absences in recent years to stop or delay votes on bills they don’t like. Their absence in 2019 prevented legislators from passing a bill to lower the state’s carbon emissions and forced the 2020 session to end days before the constitutional deadline, leaving dozens of issues unresolved.

The state constitution says House and Senate members can “compel the attendance of absent members.” The governor can authorize state troopers to find errant legislators within the state of Oregon, and lawmakers have left the state to avoid them in the past.

If the measure passes, the provision against running for office during the next election would likely be enforced by the elections division of the Oregon Secretary of State's office, said Ben Morris, spokesperson for the Secretary of State.

Walking out has become more frequent

Walkouts used to be an infrequent feature of Oregon politics. In 2001, House Democrats left the legislative session to deny quorum over a Republican plan to redraw legislative boundaries that didn't require the approval of then-Gov. John Kitzhaber, a Democrat.

Then, starting in 2019, Republicans walked out three years in a row.

Republicans walked out twice in the 2019 session. The second Republican walkout rocketed Oregon to national headlines as lawmakers fled the state to avoid voting on a bill to reduce Oregon’s carbon emissions.

The next year, a Republican walkout over a revived version of the climate bill largely derailed the short session – only three bills passed, when short sessions often see dozens of bills get through.

And Democratic leaders ended the session days earlier than the constitution said they needed to.

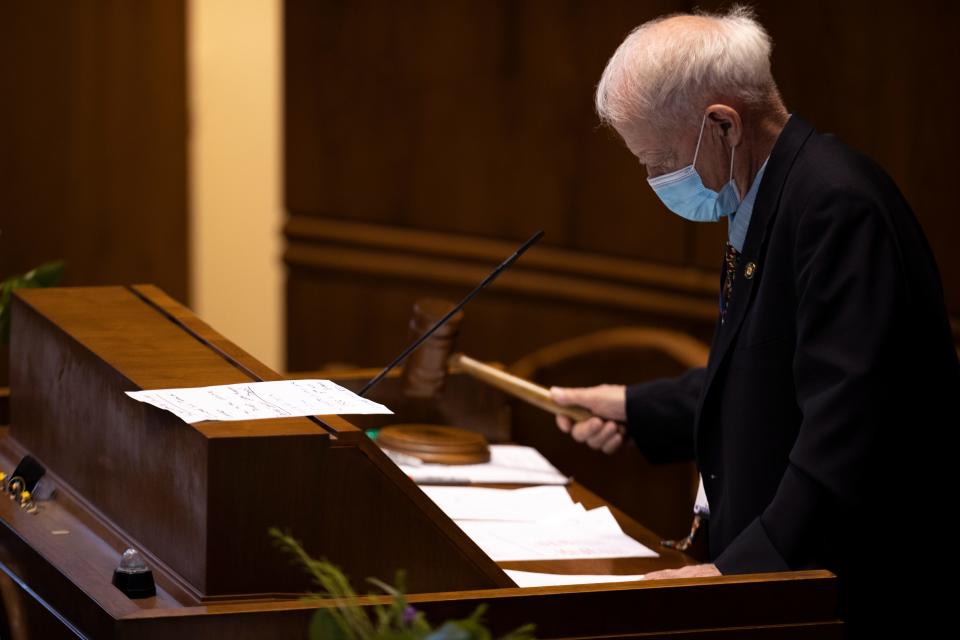

“We are going to have to, either through a constitutional amendment, or law changes, or rules, dramatically change this quorum thing,” Senate President Peter Courtney, D-Salem, said at the time.

Supporters filed a petition to disqualify absentee legislators from their next term on the ballot later that November, but signature gathering was curtailed by the COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing requirements.

So supporters filed another petition in December 2020 to aim for this year’s ballot. This summer, they got enough signatures to qualify.

In between, Senate Republicans boycotted a floor session in February 2021 to protest Gov. Kate Brown’s policies to contain COVID-19, including school closures. In September 2021, House Republicans walked out during a special session to protest a plan to redraw Congressional and legislative district maps.

Legislative gridlock

Backers of Measure 113 say voters deserve lawmakers who show up.

Reed Scott-Schwalbach, president of the Oregon Education Association teachers union, was one of the petitioners to get the measure on the ballot.

“Every day counts,” Scott-Schwalbach said. “And we believe that that is true for not only our students, but also for those who've been elected to help lead the state and create public policy.”

Scott-Schwalbach said the walk-outs hampered progress on legislation.

"It stalled the process for public policy being made in a significant way," she said. "We elect folks to go to the Legislature, to go to committee meetings, to be on the floor, to debate and then to vote."

She pointed to the Student Success Act, a bill raising $1 billion per year through a new tax to fund Oregon’s K-12 schools, which Republicans walked out to avoid voting on in May 2019.

“To hold our students, to hold our communities hostage, is just not a good way to be able to legislate," Scott-Schwalbach said. "And it's not just educators who feel really strongly about this.”

A political action committee for the petition raised about $1.5 million in cash contributions, mainly from public employee unions, elected officeholders who are Democrats and environmental groups.

Now that the petition has qualified for the ballot, the political action committee for the petition has given about $65,000 to the committee for the ballot measure, as of Sept. 16, according to online campaign finance records maintained by the Secretary of State.

A PR tactic?

Oregon Republicans have gained notoriety — and not much else — for packing up and leaving legislative sessions in recent years, said Jim Moore, associate professor and director of political outreach at the Tom McCall Center for Civic Engagement at Pacific University.

"The walkouts don't really get them anything except publicity," Moore said.

Republicans who walked out became subjects of fascination, criticism and bemusement in the national press, from CNN to Vice News, which interviewed Sen. Tim Knopp at his Idaho hideout.

But some Republicans have claimed walking out is one of the few ways they can exercise influence when Democrats have cemented most of the political power.

Republican nominee for governor Christine Drazan led Republicans in the House during the 2020 and 2021 sessions.

During a candidate debate in July, she said “the need to stand in the gap was essential and critical” when she and other Republicans walked out to avoid voting on the climate bill in 2020.

Drazan said they walked out “because we had no other options after making 100 amendment proposals that were rejected by the single-party control.”

Oregon governor's race:

Democratic nominee for governor Tina Kotek, the former Speaker of the House, countered later in the debate that Republicans hadn’t proposed solutions.

“As someone who sat in rooms, particularly with Leader Drazan, no solutions were laid on the table, it’s just ‘We don’t like it,’” Kotek said. “And when you have a challenge as big as climate change and you’ve gone through a two-year process to develop a piece of legislation that is market-driven and would benefit many parts, particularly rural parts of our state, to be part of the transition to renewable energy and to have that fail, that was just saying to Oregonians, ‘I’m going to throw in the towel.’”

Even though Republicans have defended the walkouts, there doesn’t appear to be any formal opposition to the measure yet in the form of a political action committee raising money to encourage voters to vote against it, according to campaign finance records.

Knopp, who now leads Republicans in the Oregon Senate, told the Statesman Journal he wasn’t aware of any campaign against the measure.The Oregon Republican Party could not be reached for comment by the Statesman Journal by deadline.

What do Oregonians think?

Drazan’s emphasis of the walkouts may resonate with her party’s voters, Moore said.

"She's basically saying, 'I stood up to Kate Brown and stopped these things,'" Moore said of Drazan.

For some Republicans, Moore said, the walkouts may show their legislators exhibited leadership and were "stopping what they see as kind of this wave of Democratic and big city ideas.”

But that argument might not hold water for most Oregon voters.

A survey of 1,000 Oregon voters in February 2021 indicated 84% would support a measure to disqualify lawmakers with 10 unexcused absences from their next term, according to results of research conducted by GBAO Strategies commissioned by the No More Costly Walkouts Coalition, the groups that support curtailing walkouts. The margin of error for the poll’s questions about the ballot measures is plus or minus 4.4 percentage points.

In early 2022, the Oregon Values and Beliefs Center, a nonpartisan public opinion nonprofit, found that 62% of Oregonians indicated they were "not very" or "not at all optimistic" that Gov. Kate Brown and lawmakers would make progress on issues facing the state in this year’s legislative session.

The survey of 1,400 Oregon residents was conducted online, and the margin of error for the whole sample ranges from plus or minus 1.6 to 2.6 percentage points.

The survey didn’t address walkouts specifically, but several respondents brought them up when invited to elaborate on their answers, according to the Oregon Values and Beliefs Center.

"A vocal minority brings things to a complete halt when they don’t get their way," one person said. "How could we feel optimistic."

Subverting norms — or upholding founding values?

The campaign for Measure 113 has framed the walkouts as a failure by lawmakers to show up to the jobs they were elected to do.

Democrats also say frequent walkouts threaten political norms.

“This institution has been dramatically hurt,” Courtney told reporters in March 2020 after he and Kotek ended the legislative session early due to Republican walkouts.

“Four walkouts,” he said, holding up four fingers for emphasis, his voice rising. “It is going to become a norm. You want to kill a bill? Just walk out!”

Some also view the phenomenon as part of a concerning anti-democracy trend in the U.S. – in line with false claims that the 2020 election was “stolen” or fraudulent, which prompted the violent attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

"The walkouts are going to resonate more with Republicans who are Trumpists and Trumpists in the sense that they look and say, ‘Extraordinary measures to stop the government are fine,'" Moore said. "It certainly isn't an attack on the Capitol building, but it is out of the realm of what you normally expect from a legislature."

But others view denying quorum as part of the country’s political tradition and protecting against "tyranny of the majority."

In 1840, Abraham Lincoln jumped out a first-floor window to avoid a quorum while serving in the Illinois Legislature, according to Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts. (It didn’t stop the vote).

They also point to the fact that Democrats have used walkouts in the past: in 2021 in Texas, and in 2001 in Oregon over a redistricting plan that Republicans tried to pass not as a bill but as a resolution, which couldn't be vetoed by Democratic Gov. John Kitzhaber.

“It really comes down to, ‘If you disagree with our policy positions, then you shouldn’t have the right to use any tools to dissent from it,’” said Dru Draper, political director for the Oregon House Republicans. “So we think that just curbs the voice and the rights of the minority, and we generally don’t think that’s a good thing.”

Minority party could lose leverage

If the measure passes, that could mean Republicans would lose leverage because they’d need to return before the 10-day cutoff if they want to keep their seats after the next election.

A guide to voter rights in Oregon: What you need to know before you cast a ballot

Democratic leaders could just wait them out.

Republicans could continue to have influence on the process by being "really active" in policy committees, Moore said.

The minority party could still find ways to walk out and stall legislation – say, if there were fewer than ten days left in the session. Or if enough members didn’t want to file for reelection anyway.

"It seems to leave it open to shenanigans to me," Moore said.

Claire Withycombe covers state government for the Statesman Journal. You can reach her at 503-910-3821 or cwithycombe@statesmanjournal.com.

This article originally appeared on Salem Statesman Journal: Measure 113 would make walkouts trickier for Oregon lawmakers