Pablo Escobar's legacy is an 'open wound' in Medellín. But tourists can't get enough of it

Three decades ago, this bustling metropolis was the world’s most dangerous city, an epicenter of assassinations, massacres and car bombs linked to the eponymous hometown cartel and its notorious boss, Pablo Escobar.

Even after Escobar’s shooting death here on a rooftop in 1993, the culmination of a massive manhunt by Colombian authorities aided by U.S. drug agents, levels of violence akin to open warfare continued to batter neighborhoods like Comuna 13, where guerrilla bands fought it out with soldiers, paramilitary gunmen and police.

Today, Medellin, home to 2.5 million, is benefiting from a stunning turnaround, drawing record numbers of tourists from the United States and elsewhere. Once atop the global homicide list — the city saw almost 19 slayings daily in 1991, in the heyday of the now-defunct Medellin Cartel — the rate of killings has since dropped well below that of many Latin American and U.S. cities.

These days, the city’s turbulent past, especially the legacy of Escobar, has emerged as a major tourism draw. A profound international fascination focuses on Medellin’s dark side. Articles, books and dramatizations about Colombia’s cocaine cartels, notably "Narcos," the popular 2015-16 Netflix series, have amplified the allure of so-called narco-tourism.

“Once Netflix came out with 'Narcos,' that’s when everything blew up,” said Luis Ospina, one of many guides who provide tours of sites linked to Medellin’s violent past. “We started getting Europeans, Americans, mostly English-speaking tourists."

Visitors seek out traces of Escobar’s sanguinary reign while also making the trek to Comuna 13 to hear stories of revolutionary mayhem. In addition, tourists frequent upscale cafes, bars and shopping venues in swanky zones like El Poblado and Laureles, and peruse galleries featuring the paintings of Fernando Botero, a Medellin native and perhaps Colombia’s best-known artist.

Escobar, though, has become a commodity. He may have been best avoided in life, but in death a lot of people want a piece of the action. Key destinations on the narco-tour are the gritty Barrio Pablo Escobar, where the drug lord helped build hundreds of homes for impoverished residents, many former denizens of a city dump; the tree-lined Los Olivos zone, where police snipers shot a barefoot Escobar, 44, on a rooftop on Dec. 2, 1993, as he tried to escape; and the cemetery where the billionaire’s remains were interred.

A museum run by family members in what they call a former “safe house” features Escobar artifacts — a bullet-riddled Mercedes sedan, the remains of personal aircraft, a Wet Bike (an early jet-ski featured in the 1977 James Bond film, "The Spy Who Loved Me," which dazzled Escobar), and desks with hidden compartments in which millions of dollars were supposedly stashed — along with themed merchandise: liquor bottles, T-shirts, keychains and coasters, all embossed with the former capo’s mug.

Despite the profligacy of Escobar’s image, his legend is a point of considerable tension and a battle about memory. Many, perhaps most, in Medellin revile him as a homicidal fanatic who turned the town into a free-fire zone. The sight of tourists wearing Pablo Escobar T-shirts is especially repulsive to many.

“If you go to Berlin, you don’t buy a Hitler T-shirt,” noted Marcelo Jaramillo, whose tour company offers a "transformation of Medellin" itinerary, but not a specific "Pablo tour" that some guides offer.

Those who lived through the city’s bleak days, he said, generally prefer not to talk about it — much less glorify the gangster behind the carnage.

“It’s still an open wound,” said Jaramillo, 40, who was a youth when chaos defined his hometown. “That doesn’t change with a television series.... The city is still split between these two worlds, between the dark and the light. And both sides benefit from tourism.”

But a minority still view Escobar as a kind of Robin Hood who built homes and schools for the poor and erected soccer fields and power lines as he rose from humble origins and a career in car theft and other petty crime to the Forbes list of the world’s wealthiest individuals. His aura seems only to grow with the years.

“You can’t say anything bad about Pablo Escobar around here,” said María Diocelina Guerra Willis, 85, a grandmother who still lives in a home in the Barrio Pablo Escobar that she says is hers thanks to the late trafficker’s generosity. “It is because of Pablo that we have this place.”

Up the concrete stairs that mark the hillside barrio, Edwín Alexander Montoya, 20, and María José Jaramillo Montoya, 8 — siblings who reside in a home that they say was gifted by Escobar to their grandmother — display for visitors framed photos of the late drug baron. "For us, God has forgiven Pablo for everything he did, and he is with him now in his Holy Glory," said María Eugenia Castaño, 47, mother of the two. "We have a lot to thank him for."

Rumors persist that Escobar is still alive, mocking his pursuers — even though thousands of mourners attended his raucous wake and funeral in 1993. “I think that Pablo is in Buenos Aires [Argentina],” said Luis Felipe Méndez, a Colombian tourist visiting the neighborhood. “He is alive. I believe it.”

Alternately, some refuse to give credit to police for Escobar's ultimate demise, insisting that the fatal shot to Escobar's head as he was being chased was a case of suicide.

A mural of Escobar’s mustachioed visage — featuring his trademark leering smile and bald-spot comb-over — welcomes hundreds of visitors who arrive weekly, often in tour vans, to Barrio Pablo Escobar, where a kind of shrine exalts the former cartel chieftain. Peering down from an elevated niche is a likeness of the Holy Infant of Atocha , a figure of Roman Catholic devotion that was beloved by Escobar's mother.

A gallery features a mannequin of Escobar holding a walkie-talkie — with a pair of AK-47 rifles mounted on the wall behind him — amid a greatest-hits array of images: A defiant Pablo in police mug shots; Pablo as a glad-handing politician (he once aspired to be president); a grinning Pablo in family snaps, pressing the flesh at sports and vacation venues. A mural depicts the entry to his infamous rural getaway, Hacienda Napoles, which featured, among other attractions, a zoo from which imported hippopotamuses have since escaped into the nearby countryside, causing environmental havoc.

Handwritten comments in a guest book at the gallery site attest to the ongoing appeal of Escobar.

“Dear Pablo,” wrote Felix Malanog, a 25-year-old Californian, in an entry dated May 30, 2022. “I hope that you are doing well in heaven right now. Too bad, I wasn’t born during your time. Thanks for the memories that you created in Colombian history and to the world. You are a legend.”

The Escobar fascination also fuels a thriving memorabilia market.

“His whole story is just amazing,” said Jani Perkonmäki, 46, who has turned part of his home in rural Finland into a kind of Escobar museum, featuring photos and mementos — including what he says is one of the mobster’s shirts, a pair of his aviator shades (in their original leather case), a pager and a transistor radio. “Yes the deaths are very sad. And I don’t support this violence," he said by telephone from his home in Hameenkyro, Finland. “But how can one person accomplish all that Pablo did?”

A frequent visitor to Medellin, Perkonmäki hopes to move here. Tattoos of Escobar and other cartel members embellish his body. A tattoo on his back, next to a life-size image of Escobar’s face, reads “Plata o Plomo,” literally, Silver or Lead. It was a signature cartel threat demanding that debtors pay up or face a cheerless alternative — a shower of lead, i.e., bullets.

With permission from the Escobar family, Perkonmäki said, he is planning to market in Europe a Nordic-style cocktail — gin and grapefruit juice — featuring Escobar’s face on the label of cans and bottles.

Adam Chaitin-Lefcourt, a criminal defense lawyer who runs a boutique California caviar company, said he first went to Medellin on a whim in 2017 but soon got deeper into the Escobar saga, though he deplores the violence and loss of life.

“Look at Tony Soprano — why are so many people attracted to that?” said Chaitin-Lefcourt, 37, referring to the protagonist of the HBO series. “It’s the allure of the anti-hero.... Anyone, as long as they have the intellect, desire and ingenuity, no matter the depth of depression and poverty, can pick themselves up to become one the most famous, influential people in the world.”

He plans a return trip to Medellin. He’s looking to purchase a bag, crafted from the fur of a wild spotted cat, from which Escobar is said to have dispensed cash to the needy.

The Escobar mystique is not something that Medellin’s city leaders embrace. They prefer to stress other charms in a town featuring a diverse culinary scene, a burgeoning high-tech industry and a balmy climate — “The City of Eternal Spring,” as Medellin, nestled in the Andes and perennially dappled with flowers, is called.

“Today, Medellin has gone from being the most violent city in the world to being a center for science, technology and innovation,” said Alejandro Macías, the city’s tourism secretary. “We can’t deny our history. But we are seeing a new narrative in which Medellin is transformed.”

Petty crime remains a problem, especially in rough precincts in and around downtown. Some tourists come for drugs and sex, mixing with criminal elements. Mafias are keeping a lower profile but remain a force in Medellin, experts say, controlling drug smuggling, human trafficking, money laundering and other rackets in Colombia’s second city.

"The Medellin Cartel is gone," noted Pedro Piedrahita, a political scientist at the University of Medellin. "But Medellin remains one of the primary logistical centers for transnational organized crime."

Still, the sight of foreigners lugging laptops in their backpacks, seeking daily workspaces, is testament to the large numbers of so-called digital nomads from the United States and elsewhere calling Medellin home. With favorable exchange rates, some are purchasing condos in the multi-storied towers that soar up the verdant slopes. For many expatriates, the Escobar period is little more than a historic curiosity.

“Some Americans still believe in the Medellin of Netflix’s 'Narcos' — but it’s not that anymore,” said Croix Sather, 51, an author and inspirational speaker who splits time between here and the United States. “I was scared when I got here, but quickly learned that the city is not dangerous like the perception.”

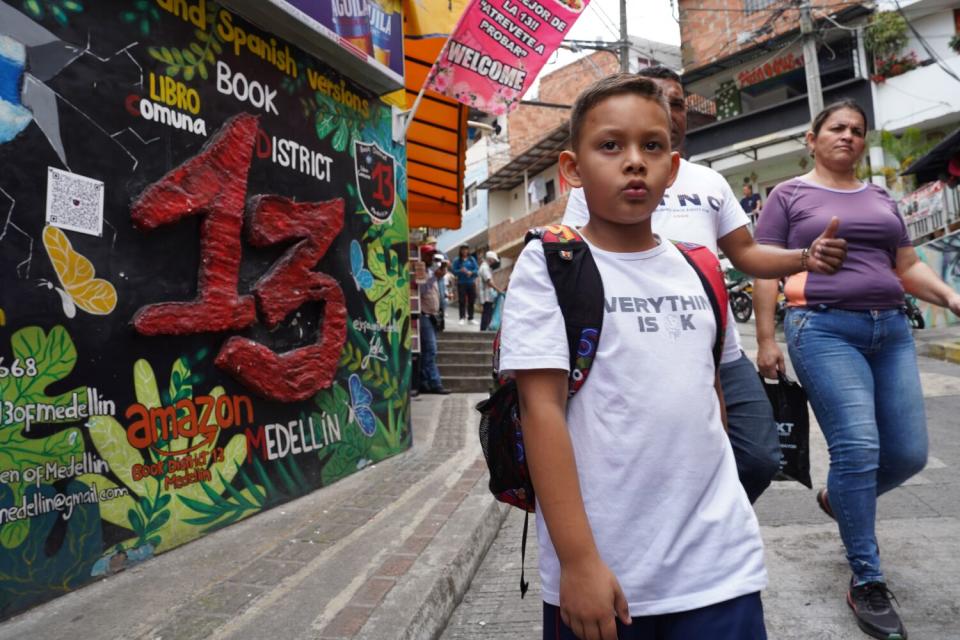

The transformation is especially evident in the sprawling hillside Comuna 13 neighborhood, home to some 150,000. Comuna 13 was largely a no-go area for police during the 1990s and early 2000s, when it was Colombia’s largest urban rebel stronghold. A series of military operations scattered the guerrillas, but also left many civilian casualties and lingering bitterness.

Residents reclaimed their neighborhood, and turned it into an improbable cultural and tourist hotspot — now visited by 12,000 or more each week, making it one of Colombia’s most popular tourist destinations. It is a venue for street art, hip-hop performers, rappers, traditional musicians and oral historians recounting the trajectory of the barrio, all amid a plethora of galleries, bars and restaurants, many with blaring music. A carnival atmosphere prevails.

“Armed groups used to come down from the hills, force people on their knees and execute them right here,” said Jhona Marín, 27, a Comuna 13 native who now guides visitors to the district. “Dead people in the streets — that used to be the norm here.”

Alejandra Mejía, 21, one of many young entrepreneurs in Comuna 13, deploys a drone to snap photos of tourists with a backdrop of panoramic views of the city. Visitors line up for the souvenirs.

Colorful murals tell the history of Comuna 13’s re-imagining. Six escalators help residents and visitors climb the steep slopes of the community, which bears a resemblance to the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. The frequent elephant motifs spray-painted on walls carry a message: The people of Comuna 13 don't forget their past.

That is the point, too, at Medellin’s Inflexion Memorial Park. The contemplative monument was built on the site of Escobar’s former fortress, the Monaco Building, which the city demolished in 2019 as part of its effort to reshape the collective memory. A sloping wall of black granite now features 46,612 perforations — one for each person lost to drug violence during Escobar’s rule as Colombia’s cocaine king, including hundreds of slain police officers.

Among the carved inscriptions at the site are the words of Hernando Baquero Borda, a Colombian Supreme Court judge who handled U.S. extradition requests, fiercely resisted by drug lords. In 1986, assassins on a motorcycle shot the jurist and two others dead.

The judge’s now-memorialized words: “We are what we leave to others.”

Special correspondents Liliana Nieto del Río in Medellin, Jenny Carolina González in Bogota and Cecilia Sánchez in Mexico City contributed to this report.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.