When media gets it wrong: Why we're correcting a 103-year-old obituary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

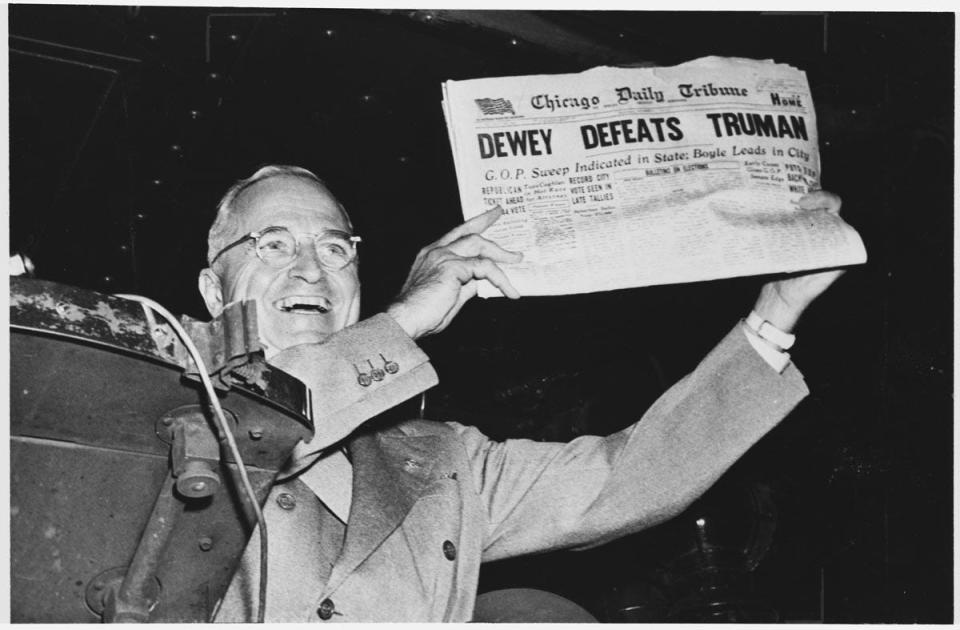

"DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN."

The most famous headline in history was not the cleverest. It was not the best written. It owes its notoriety to just one thing: It was wrong.

Dewey did not defeat Truman. Which is why the iconic photo of a gloating Harry Truman, holding up the Nov. 3, 1948, Chicago Daily Tribune, is a classic piece of Americana. Today, copies of that famed first edition go for $2,000.

Ever wonder if the Tribune ran a correction?

The answer appears to be: It didn't.

"The editors did write an explanation," said Kori Finley, the Tribune's resident historian. "I wouldn't call it an apology."

The polling had been bad, they said the next day. "We are frank to say ... we were as far off the mark as everybody else." But they never actually said, "We printed wrong information." Much less a whopper of historic proportions.

Some 150,000 copies of that first edition went out before the Tribune quietly issued a second. "DEMOCRATS MAKE SWEEP OF STATE OFFICES" was the new banner headline.

And isn't that, grumble media critics, just like a newspaper? They make mistakes, and don't acknowledge them. Or else the mistake appears in a 48-point headline on Page 1, and the correction appears three days later in small type at the bottom of page 8.

In fact, the idea of regular, formal "corrections" — much less a "corrections department" — hardly existed back in that era, said Kevin M. Lerner, an associate professor of journalism at Marist College. He's written at length about the process by which journalists correct themselves. Or don't.

"Newspapers were an industry," he said. "Publishing a new edition was a matter of mechanics. The first batch is defective. So get a new one. You don't necessarily have to correct the first one."

'Just a typo'

Most media mistakes, of course, are not on such an epic scale.

Reporters who write "climatic" when they mean "climactic." Or "Goldstein" when the name is "Goldstine." And who don't catch the error, even when they read it over five times. Carelessness, deadline pressure and mental exhaustion are typically to blame.

"Even today, the vast amount of corrections are not about who was elected president," Lerner said. "They are about the spelling of someone's name, or the hours of a local business. It's actually fairly rare when a news publication is putting out a significant mea culpa."

Which is not to say that small mistakes don't matter. They do. They matter to the credibility of the profession. They matter to history. Old newspapers are a primary source for researchers: We get it wrong, they get it wrong.

And they matter — often a great deal — to the people who have been misquoted and misspelled.

One such mistake has given Mary Ronda's family pain for 103 years.

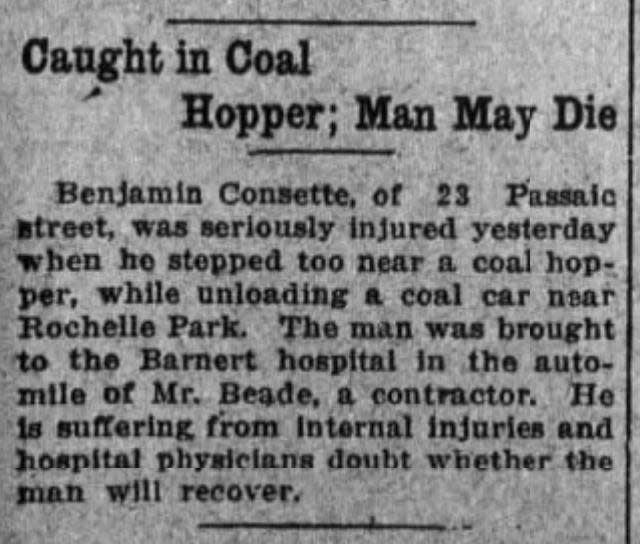

On June 8, 1919, her grandfather, Beniamino Calvitti, was seriously injured on the job in a railroad yard in Rochelle Park. Employed as a laborer for a family-owned business — wood and coal dealers in Paterson — he'd "stepped too near a coal hopper while unloading a coal car," wrote The Morning Call of Paterson on June 9. The next day, the paper carried the story that he had died after being "seriously crushed."

Only his name, in both stories, did not appear as Beniamino Calvitti. It was printed as Beniamino "Consette."

Which is why, for 100 years, three generations of Ronda's family have been unable to find any information about him. For all intents and purposes, he had vanished off the face of the earth.

"It bothered me and bothered me that there was no obituary," said Ronda, a Franklin resident. "This man died, and nobody cared? It wasn't even in the paper that he had passed away."

It wasn't until last month, when a friend thought to search through the newspaper archives by address, rather than name — who died at 23 Passaic Street on June 10, 1919? — that they were able to find the obituary for "Beniamino Consette." It was her grandfather. All the details fit.

"They had misspelled his name," Ronda said. "No wonder I couldn't find anything."

It's even possible to guess how the reporter (there are no bylines) made the mistake. The man's wife, Giovina — Ronda's grandmother — did not speak English. At the time of the tragedy, the people at the scene were getting their information from the couple's son, Diodato. He was 8.

Either he didn't speak clearly, or — just as likely — the reporter didn't listen well.

"There was probably chaos in that house," Ronda said. "He was probably crying, and when he said the name the reporter just thought that's what he said. It wasn't the reporter's fault. I don't blame anyone."

Beckerman:Your ultimate Thanksgiving guide for what to buy, cook, eat and drink

Making amends

It has fallen to The Record, which purchased The Morning Call of Paterson in 1964 (it ceased publication in 1969), to rectify the error. On page 3A on Sunday, Nov. 27, 2022, you will find — a mere 103 years late — an official correction. With our sincere apologies to Ronda and her family.

"I'm delighted she brought that to our attention," said Daniel Sforza, executive editor of The Record.

"Journalists are like anyone else — they make mistakes," he said. "But it's imperative, in terms of our bond with our readers, that when we make a mistake we own up to it, and set the record straight."

Like most media outlets today, The Record and NorthJersey.com has a specific protocol for handling corrections.

First, an investigation to determine that the mistake is a mistake — not, say, just a difference of opinion. Then, if an error was indeed made, an online correction, with an editor's message noting the earlier lapse. In print, the correction appears, at the earliest opportunity, on Page 2.

As a matter of policy, we don't repeat the mistake in the correction. "The last name of a man who died in Paterson in 1919 was incorrect on Page 1 of The Morning Call on June 9, 1919. He was Beniamino Calvitti," is how we would probably phrase this one.

Journalistic blunders, like the poor, are always with us. But the idea of a dedicated space for acknowledging mistakes is actually fairly new, said Lerner, the Marist professor.

"What we think of as the newspaper's role as an essential part of democracy is a fairly recent invention," said Lerner, author of “Provoking the Press: (MORE) Magazine and the Crisis of Confidence in American Journalism."

"There were periodic calls for various kinds of accountability," he said. "Press critics cropped up now and then. But they weren't systematic. I don't think for the most part the reading public was so concerned about the exactitude of facts. Remember the stories of the Moon Bats?"

In 1835, the New York Sun announced the discovery of life on the moon. Unicorns and bat-winged people — visible, apparently, through a wonderful new telescope — were the subject of six articles. Earthshaking news. Which, curiously, you will not find in any modern book on astronomy.

"They certainly never ran a correction on that, or even mentioned it again after the fact," Lerner said. "They moved on."

Newspapers got better later on. But not by all that much.

Blink, and you miss it

Until 1972, corrections — when they happened at all — were "filler," haphazardly sprinkled here and there, in small type, at the end of columns that had happened to run a little short (this was back in the days before computers made layout an exact science).

At the New York Times, there had been discussion for years about a better way for the Paper of Record to formally correct itself. But it took a 1972 essay in the conservative magazine "Commentary" by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, then-adviser to President Richard Nixon, to spur the staff to act.

"As to the press itself, one thing seems clear," Moynihan wrote. "It should become much more open about acknowledging mistakes."

On June 2, 1972, the Times rans its first correction in a space dedicated for that purpose.

"The obituary of Theodore L. Bates in yesterday’s New York Times reported that Mr. Bates had once briefly served as a consultant to Investors Overseas Services. Actually, it was T. Rosser Reeves, a former chairman of Ted Bates & Co., who worked for the mutual fund organization."

Doubtless, this mea culpa was important to Ted Bates & Co., if no one else.

From then on, corrections appeared on the News Summary & Index page — not A-1, to be sure, but a prominent section front where most people went to get their daily news digest. Other papers followed suit. By 1973, nine out of 38 major newspapers (100,000 circulation or more) had a dedicated "corrections" section.

"If newspapers see themselves as the first draft of history, this is going back and revising that draft to some extent," Lerner said.

Misstatements of fact are one kind of error. Wrong spellings, wrong dates, are pretty cut-and-dried. But there are other, more controversial mistakes. Errors of bias, omission, judgment.

The Times had been mulling this, too. Editorial writer A.H. Raskin had proposed in the 1960s an idea of an "ombudsman," an independent observer who could field complaints from readers and objectively analyze them in print. But it was apparently two Louisville, Kentucky, papers, the Courier-Journal and the Times, that were the first, in 1967, to institute such a thing. The New York Times and other papers followed.

"My sense is, 20 years ago might have been the peak of that, the high point of newspaper corrections," Lerner said.

Setting the record straight

How effective are corrections? Sometimes, Lerner suspects, they can be more performative than anything else.

"It's a way of saying: Look how much we care about the facts," he said. "If this is how much we care about these little things, imagine how much we care about the big things."

But in the end, how many slip-ups are actually acknowledged? Still not enough, he would say.

"When reporters get it wrong, they may not want to report their mistake to the corrections desk at the paper, because that's admitting a mistake, and they think it goes on their permanent record — and it may," Lerner said. "There are institutional reasons not to report mistakes up the chain."

But it's important for reporters to self-correct. It's key to credibility. More so now than ever — when the news media is increasingly under attack by bad actors, with their own agenda for trashing the folks who at least try to get the story straight.

It's also important to readers. As Mary Ronda and her vanishing grandfather bear witness.

"It was like he died and disappeared," she said. "He didn't exist anymore. Finding that obituary feels like closure."

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: When should newspapers run corrections? We examine an old obituary