Meet the former federal prosecutor who wants to abolish prisons

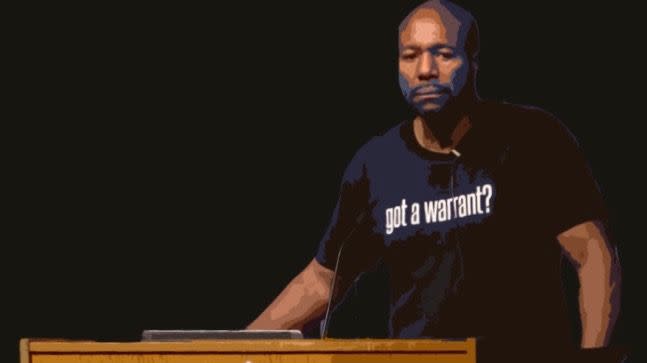

Georgetown Law professor and author Paul Butler knows the US criminal justice system, personally and professionally, inside and out.

As a former prosecutor, he once fought to have defendants locked up for a very long time. He’s also been arrested himself, standing trial for a crime that he didn’t commit, and for which he was acquitted.

Now he’s advocating for the abolition of prisons. While that sounds extreme, Butler’s approach is quite reasonable.

He’s not saying there should be no consequences for criminality. Rather, he’s asking, “Are there ways we could accomplish the goals of prison more effectively?” Asking the question puts him in some highly esteemed company indeed.

The finger pointing at itself

Prison systems have always been morally problematic. On the one hand, societies want to punish those who disobey the laws and keep those who follow them safe. On the other hand, mistreatment of the incarcerated has long reflected poorly on the morality of the free, as US founding fathers Benjamin Franklin and Benjamin Rush—both signers of the Declaration of Independence—noted in 1787 when they started the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons.

Franklin and Rush were committed to certain principles still worth considering today. They argued that society’s obligations to its members do not end when someone is convicted of a crime. And so compassion must be extended to prisoners, who mustn’t suffer unduly. “Such punishments may be devised as will restore them to virtue and happiness,” they wrote. “The links which bind the human family together must under all circumstances be preserved unbroken—there must be no criminal class.”

Despite those noble sentiments, today, there is a criminal class in the US. It’s disproportionately comprised of African American and Latino men, says Butler. Between 1980 and 2015, the number of people incarcerated in the US increased from roughly 500,000 to over 2.2 million. The US, home to about 5% of the world’s population, now accounts for 21% of the world’s prisoners. According to the NAACP, in 2014, about 34% of that US prison population was made up of African-Americans. Blacks and hispanics constituted 56% of individuals incarcerated in 2015, but only 32% of the total US population.

These alarming figures are the result of systemic racism. In 2010, the civil rights activist Michelle Alexander wrote a book called The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, comparing the modern US prison system to laws that enforced racial segregation in the South in the late 19th and early 20th century. Butler agrees with this formulation and uses it himself. Police target and arrest minorities at much higher rates than they do whites. Blacks are five times more likely to be arrested than whites, to be precise.

The consequences of arrest are dire even for those who are acquitted of crimes because the criminal justice process is itself a punishment that costs the accused time, money, jobs, and freedom, and causes indescribable stress. For those who are convicted even of non-violent crimes, the price is much higher, resulting in permanent disenfranchisement from society. A criminal record dictates the kind of jobs people can find and, in some states, whether they can vote, and it perpetuates a cycle of poverty and alienation that is a moral stain on all of us.

Up close and personal

Take it from Butler, who both saw the injustice up close and was part of the system that perpetuates it. In the 1990s, he was a federal prosecutor in the Department of Justice, where he worked hard to secure convictions and long prison sentences. For years, he dismissed defendants’ claims that police targeted them or lied about crimes. He pressed them on cross-examination, incredulously asking, “You mean to tell me that police officers had nothing better to do than to invent a story about you?”

Then the tables turned. Butler, who attended Harvard and Yale universities after growing up in a poor Chicago community, was arrested over a dispute with a neighbor and, he told The Guardian, falsely charged with a misdemeanor assault. After his arrest, he found himself in the very same Washington, DC, courtroom where he sometimes practiced law himself. Mortified, he hoped the judge wouldn’t recognize him. And Butler was relieved and dismayed to discover that in this new context, as a defendant, he was invisible.

The judge didn’t recognize him because he didn’t even look at Butler, much less put his name and face together with that of the prosecutor who argued before him. Ultimately, the lawyer was acquitted after a trial—the jury took only 10 minutes to find him not guilty. But the experience dramatically changed Butler’s worldview. He understood firsthand that cops do lie sometimes. And he believed that witnesses might avoid coming forward with exonerating testimony, because the witness in his matter refused to come forward to assist him. “It made me a man,” Butler says of the experience. “It made me a black man.”

After his acquittal, Butler could no longer ignore the glaring injustices he had seen and been part of. He understood that he had been lucky, relatively speaking: He was acquitted not just because he was innocent, but also because he had the means to hire a fantastic lawyer, as well as impressive credentials himself. And suddenly, he faced all the uncomfortable things he’d been pushing aside—the way his fellow prosecutors talked about minorities derogatorily, calling them “douchebags” and “cretins”; the fact that they measured success by their tallies of convictions and long sentences; the fundamental corruption of a system that institutionalizes racial injustice.

The way to succeed in the work Butler was doing was to secure convictions—that was just the workplace culture. As a competitive and ambitious attorney, Butler did what he could to get ahead, and he was successful. He says he justified his actions by telling himself he was doing necessary work. But when he went to Washington, DC Superior Court as a defendant, he was forced to face the question he’d long ignored: “Where are all the white people?”

As a law student, Butler never would have predicted that he’d turn into a vicious prosecutor. But he had. Now he admits that he started out wanting to change the system from within and discovered instead that it changed him. And so he pivoted, transitioning from an arm of authority to an authority on resisting the system and one who advocates for its transformation.

Butler’s 10 commandments

On Jan. 18, Butler released a video called “10 Commandments for Black Men,” which he describes as “dead serious advice for everyone but especially black men.” The video is modeled on the horror movie genre to evoke the nightmarish reality of life for some in the US. “The country that black men live in is not free,” Butler tells Quartz.

In the video, Butler lays out advice on how to avoid confrontations with cops and how to behave when it happens anyway. He acknowledges that following the rules doesn’t guarantee safety or freedom—indeed, the video is based on a chapter of his 2017 book Chokehold: Policing Black Men, which he wrote after the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, and Freddie Graham. All are African-Americans who were killed as he was planning his text; all their deaths, in his view, stem from systemic racism.

Initially, Butler’s book was intended to be a guide to the law for all. But since the law doesn’t impact all communities equally, he changed his focus to acknowledge the special circumstances that black men in particular face. “Even if African-American men did everything right, they can still be subject to brutality,” Butler says. “Police do enforce a racial kind of law and order in a system with winners and losers.”

Yet he does believe that understanding the realities of the system can help at least some people who are in a bad way avoid a worse fate, and so he provides the insights he’s acquired from decades of engagement with criminal law. Among them: Avoid baggy pants. Know that cops will notice when a group of African-American men gather or drive around together. Understand that police pay attention when they see a black man with a white woman. If you’re arrested, “shut the hell up.”

This advice can sound disconcerting to those who believe in freedom of expression. But Butler isn’t saying black men should make all of their decisions based on how police are behaving—he’s just reporting what he knows from his experience working with law enforcement officers and his research as an academic, and he wants people to be aware of what police officers notice. The idea isn’t to circumscribe people’s behavior, but to inform them so that they are best equipped to handle a police encounter wisely should one occur. And he does acknowledge that it involves putting on a sort of “performance,” as he puts it—whether or not people follow his advice, he believes that the knowledge is valuable.

That said, some argue that noting the disparities in treatment by police or in incarceration figures according to race only reenforces stereotypes, or justifies them for those who hold them. In a 2018 study in Current Directions in Psychological Science, researchers from Stanford University wrote that “the numbers don’t speak for themselves.” They found that exposure to statistics about extreme racial disparities in criminal justice can cause people to become more, not less, supportive of the very policies that create those disparities. They further argue that highlighting racial disparities paradoxically provides “an opportunity to justify and rationalize the disparities found within that system.”

The same researchers, in a 2017 study analyzing police behavior with citizens based on body camera recordings, noted that there is a racial disparity in treatment, visible from the footage. “Police officers speak significantly less respectfully to black than to white community members in everyday traffic stops, even after controlling for officer race, infraction severity, stop location, and stop outcome,” they write. Given this ingrained and widespread racism, there’s a legitimate argument that no amount of awareness or accommodation of unfairness on the part of black men can improve encounters with authority. In other words, don’t put the onus on the party without the power.

Still, Butler says that in his personal and professional experience, which is significant, the “politics of respectability” play a huge role in arrests and ultimately convictions, so connoting respectability improves, although it doesn’t guarantee, chances of a police encounter ending with a better outcome. He is unapologetic about acknowledging the performance he believes black men especially must put on to try to avoid problems with the police. “The choice is to engage in that performance that keeps me safe and that comes at a cost to free expression or risk freedom altogether,” he says.

He argues that African-American men in particular need be more aware of the system in which they are operating. And if that means there’s a tension for them between exercising constitutional rights and getting to live out their lives, a tension that others are spared, awareness of it can only help. “In terms of racial justice, black men get outsized attention from police and that means we face a special set of circumstances,” he explains. “I wanted to do something that was different from traditional civics classes or street law lessons.”

As for everyone else, he argues that some of his advice benefits anyone in a police encounter, most notably the counsel to be polite and then to refuse to speak if arrested and ask for an attorney. And even if you aren’t the target of a cop’s unwanted attention, you can still work to ensure justice, he says. If you see someone in a police encounter, especially one that’s targeting a person for their race and not their behavior—as happened last April in Philadelphia when two black men were arrested for trespassing while waiting for a friend at a Starbucks—Butler advises that you film the exchange on your phone and be willing to make it clear to police that they are not acting in your name, for your safety, or with your support.

The long view

The “10 Commandments” video is a sort of band-aid that Butler offers people dealing with the current reality. But in the big picture, the law professor says that we need a totally new approach to law enforcement. “Prison reform is too slow,” he argues. Instead, he says we need to be thinking in terms of alternatives to policing and incarceration.

For example, he believes that creating a service corps that helps people in crisis but doesn’t have the power to arrest—deployed in everyday emergencies that don’t involve violent criminality, like certain domestic disputes or drug overdoses—will help both police and the people they serve. Butler argues that deploying officers to scenes where crime is not the central problem, but there is an emergency of some kind, creates an undue burden on police and ends up with individuals being arrested unnecessarily. Since arrest is the tool that officers have, they use it to solve everything, Butler contends.

As for mass incarceration, Butler says it’s a major financial burden on society—and one that doesn’t accomplish what it sets out to do. In his view, given the glaring disparities in the application of the justice system to differing races, it’s time to start talking about a totally new approach. Drug crimes, for example, might be treated with rehabilitation and therapy instead of punished with incarceration. The mentally ill could receive counseling and hospitalization instead of prison time. And police and prosecutors could operate in a system that doesn’t just reward arrest and conviction, but the true pursuit of justice.

These arguments might have seemed extreme, and Butler’s ideas mere pipe dreams, when he first realized the fundamental corruption of a racist criminal justice system 20 years ago. But today, there’s increasing support for Butler’s perspective. He cites that movement to abolish Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) as evidence that a wider swath of society than ever before is reconsidering whether caging people really accomplishes stated policy goals.

Another example, in Vox on Feb. 12, writer German Lopez proposed a cap on maximum prison sentences. “It’s time for a radical idea that could really begin to reverse mass incarceration: capping all prison sentences at no more than 20 years. It may sound like an extreme, even dangerous, proposal, but there’s good reason to believe it would help reduce the prison population without making America any less safe,” Lopez writes. He points to studies that show long sentences don’t minimize crime and that extensive incarceration only exacerbates criminality by keeping inmates in a closed circle and making legitimate work difficult to obtain.

That same day, Los Angeles County supervisors approved a plan to tear down what the Los Angeles Times calls “the dungeon-like Men’s Central Jail downtown,” replacing it with a mental health treatment facility. Currently, 70% of the county jail’s inmates have medical or mental illnesses and the decision recognizes that simply locking people up won’t solve the problems that brought them to the county’s attention.

That’s exactly the kind of thinking Butler is advancing through his writing, teaching, public speaking, and advocacy work. Last year, he returned to Harvard, the law school he graduated from in 1986, to teach. In his last lecture in May, he advised students to use their privilege to also speak truth to power and ask difficult questions. “Prison doesn’t make us safe or punish criminals,” Butler argues. “Can we use our creativity and ingenuity to come up with a better way that doesn’t involve locking so many people up?

Sign up for the Quartz Daily Brief, our free daily newsletter with the world’s most important and interesting news.

More stories from Quartz: