Meet the Guerrilla Bike Activists Installing Bootleg Infrastructure for Safer Streets

I stood on the corner of a neighborhood in Chicago’s South Side and wondered if I had made a mistake—well, two mistakes. The first was whether I arrived at the right place to meet my contact John, whom I had never met before and who was intentionally vague about where we were meeting. The second was whether I should be doing this in the first place. After all, it was definitely illegal—and potentially dangerous.

Footsteps echoed to my right. I turned half expecting a cop to be asking me what I was doing on an empty street corner in the South Side at night—but, instead, I saw a tall man walk towards me wearing dark clothes and a mask. This could be good or very bad, I thought. I placed my bet on it being good.

“Hey,” he said. “Tony from The Daily Beast?”

Members of the People's CDOT prepare materials for the traffic calming installation.

“That’s me,” I said, trying to hide my relief. “Good to meet you.”

“Likewise,” he said, motioning for me to follow him. Soon, we arrived outside a house where several people—also donning masks and dark clothes—stood on the sidewalk. They were surrounded by what looked like construction equipment: cinder blocks, PVC pipes, and metal fittings. One person set up caulking guns as though they were loading rifles. John introduced me to the group.

“This is it,” he said to me. “The People’s CDOT.”

The People’s CDOT, or the People’s Chicago Department of Transportation, began in October 2022 in response to what John described as glaring deficiencies in the official CDOT. These deficiencies result in dangerous conditions on the streets of Chicago—endangering and claiming the lives of pedestrians and cyclists each year, according to John.

“The city doesn’t do a good job of putting safe street infrastructure where people want,” said John, whose name has been changed to protect his anonymity. “So I thought, ‘Why don’t we just build our own and put it where the people want to put it?’”

The group itself is made up of mostly cyclists who met at various other bike safety events. Together, they share the common motivation of ensuring safer streets in the city of Chicago. To date, John said the People’s CDOT has installed “10 to 15” street calming infrastructure projects. This includes cinder block posts to protect bike lanes, concrete planters to stop cars from blocking sidewalks, plastic speed bumps to slow down vehicles, and cinder block bollards to prevent cars from driving on the Lake Front Trail.

A bootleg bicycle lane barrier created by the People’s CDOT out of cinder blocks.

These projects were initially self-funded, with John and other members of the organization paying out of their own pocket for equipment they needed for installations. However, they recently put up a donation page that he says is already raising a good amount of money—which he claims underscores the public support for their activism.

“We’ve gotten a couple thousand dollars from folks in the past couple of weeks alone,” he said. “It’s been great.”

The majority of the group’s projects originate from requests from community members who reach out over Twitter asking for help. Maybe their kids play on a street where cars frequently speed by. Or maybe a cyclist was hit while traveling down a bike lane and a truck merged into them. When this happens, the People’s CDOT will arrive in the area with equipment on hand to correct what they see as a failure of the city to properly protect its citizens from traffic danger.

It’s a type of vigilante activism that has seen a rise in recent years in major metropolitan areas like Chicago, New York City, and Los Angeles in response to the drastic rise in pedestrian deaths in recent years. A report released in June by the Governor’s Highway Safety Association found that drivers hit and killed more than 7,500 pedestrians in 2022—the highest number of fatalities since 1981. People of color represented a disproportionate amount of these deaths.

42,915 Americans Died in Traffic Accidents in 2021—the Most Since 2005

Chicago alone saw 174 pedestrian deaths in 2021—a 13 percent spike from the previous year. Even in 2020, a year that saw much of the world quarantined and on lockdown, bike crash deaths rose by 16 percent compared to 2019, and rose another 5 percent the next year, according to Streetsblog Chicago.

“Everyone from CDOT, to the mayor, and the city at large have just done such a poor job of showing people what’s possible for our streets,” John said. “So everyone just assumes that they’re for cars and driving—and everything else is a hindrance to that.”

In response, the People’s CDOT has emerged as a proactive, albeit clandestine, movement to ensure safer streets for cyclists and pedestrians—even though it’s not necessarily legal. In fact, it could fall under the definition of both vandalism and street obstruction without a permit under the Municipal Code of Chicago. Nevertheless, the group remains stalwart in its resolve to bring attention to the dangers posed by current street infrastructure—and it’s not alone.

The Crosswalk Collective (LACC) is an LA-based group of community activists who paint DIY crosswalks on busy intersections in order to ensure pedestrian safety when crossing streets. Their website even includes guides on how exactly others can paint their own guerrilla crosswalks.

The before and after of a crosswalk painted by Crosswalk Collective in Los Angeles.

“Crossing the street here in Los Angeles is a harrowing experience,” a spokesperson for LACC told The Daily Beast. “And if you have a small child with you, you notice it even more because often you won’t have enough time to cross the street, even where some safety infrastructure does exist.”

They added that the sidewalk doesn’t necessarily offer safety either because the “intersections are so poorly designed that drivers lose control and drive into buildings and restaurants on a pretty regular basis.”

The statistics bear this out. A report released early this year from traffic safety nonprofit Streets Are For Everyone found that Angelenos are dying at a higher rate on the streets than the rest of the country by a fair margin. Pedestrians and cyclists are killed in LA at a rate of 2.9 per 100,000 people—much higher than the national average of 2.2 per capita. Moreover, unhoused pedestrians are killed at a rate of 116.6 per capita. That’s 53 times the national average.

“Everything is hostile to pedestrians, from the widespread use of beg buttons to the countdown clocks that last only long enough for able-bodied adults to cross the street,” LACC said. “Cars are the number one killer of kids in Los Angeles and it’s not hard to see why.”

The People’s CDOT readied their equipment, using only flashlights and the street lamps to light their way. The plan was to install a set of street calming barriers—made of several PVC pipes adhered to cinder blocks with industrial glue—at a busy crosswalk near a school and a public park. That way if cars wanted to drive past, they’d have to slow down in order to navigate the barrier. While it doesn’t stop the cars outright, it does make drivers think twice before speeding by—and that may make all the difference.

The crew needed to work quickly though. There was a police station blocks away—steps really. There was no time to waste.

A palpable nervous energy hung in the air like static electricity before a lightning strike. Someone asked if we all had heard about the driver who struck four pedestrians outside of Guaranteed Rate Field before a White Sox game earlier that week and sent them to the hospital in critical condition. We all had. People nodded solemnly and kept working, as if the story hardened the resolve of what they were doing.

Two members of the People’s CDOT work to set up the traffic calming installation at a crosswalk in Chicago’s South Side.

“Everyone who bikes knows someone who’s been hurt,” a People’s CDOT member told The Daily Beast. “I’ve seen people get hit by cars. I’ve been hit by cars. It’s pretty bad.”

Once the materials were ready, the group transported everything by foot and cargo bikes to the site blocks away. As soon as they arrived, everyone quickly went over the plan and began working—caulking cinder blocks to the ground near the crosswalk and securing the posts with glue.

It was a Friday night in the summer, though, which meant that even in this quiet South Side neighborhood there were plenty of people walking and driving by. Occasionally, pedestrians would stop to look at what the group was doing for a while before going on their way. More often, though, cars would screech by as if to prove how much the installation was needed.

“See? That’s what I’m talking about,” another member told The Daily Beast. “Cars will do that all day and night—and the city will do nothing about it.”

One plastic speed bump can transform an intersection and save lives. If the City's CDOT won't do it, we will. We are #ThePeoplesCDOT. pic.twitter.com/kVNWYirdL2

— The People's CDOT (@ThePeoplesCDOT) December 18, 2022

The installation neared its finish. As members began attaching People’s CDOT fliers to the posts, though, an older white man began walking towards the group. He had been watching for the past five minutes. A stony look on his face steadily grew from confusion to a righteous anger that seemed to say, “Get off my lawn.”

“What are you guys doing gathering here?” he asked no one in particular. Everyone continued to set up silently. This seemed unsatisfactory to him because he asked louder, “Who do you work for?”

“We work for the people,” John said.

“The people?” He laughed, though it didn’t seem like he found any of it very funny. “Who approved this? Hey, I’m asking questions. Do you live here?”

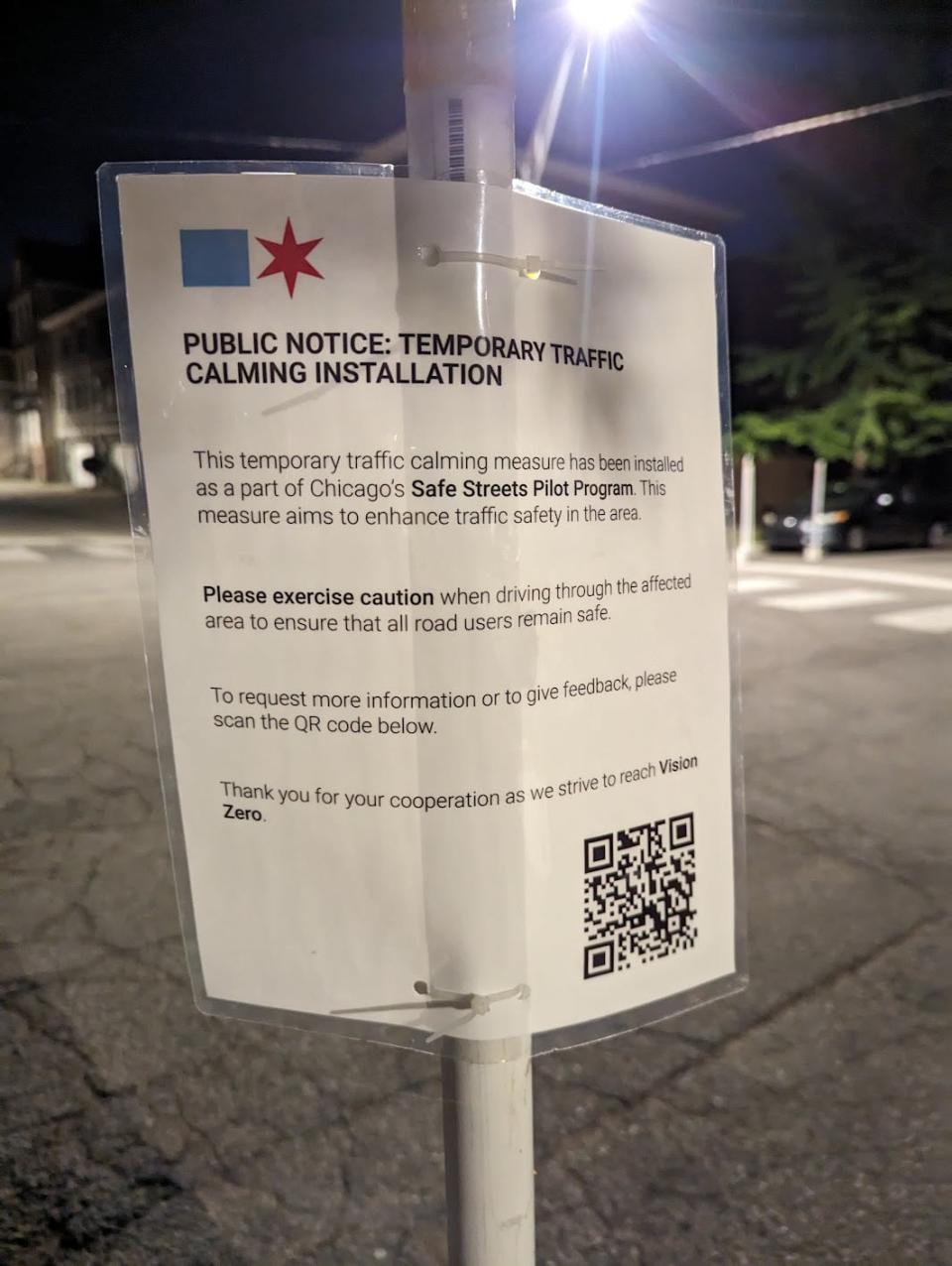

“If you want to learn more, you can fill out our survey,” John said, pointing to a QR code on one of the fliers.

The man squinted and stared at the flier on the PVC pipe. He shook his head before asking again, “Who are you?” He took one last look at the group before storming back into a house less than half a block away.

A flier from the People’s CDOT explaining the traffic calming installation.

After he left, the group finished setting up the last of the installation with a little more urgency. An angry older white guy was bad news, like how a dead albatross portends doom for sailors. For The People’s CDOT, that might mean cops—and no one wanted to go to jail that night.

Soon, they finished. The group silently gathered up all their equipment. John muttered something about going back to the sidewalk where they prepped before taking off on his cargo bike. Without another word from anyone, the group took off in separate directions as if choreographed, walking into the safety and security of the warm summer night.

“That’s the first time someone’s come up to us in a confrontational way,” John said later. “People typically come up to us in an appreciative way and to say thank you. No one’s ever directly approached us before.”

It was a few days after the installation—and John seemed annoyed.

After the group had a quick debrief on the sidewalk following the installation, everyone went home except for me. I walked back to where the group did their work—only to discover that the entire installation was gone.

For a moment, I wondered if I was at the right crosswalk. Not even five minutes had passed since we left the area. That’s when I noticed a pile of cinder blocks and PVC pipes against the fence of the park. Outlines of caulk and glue from where the cinder blocks sat remained on the street.

Someone—likely the angry old white guy—came by and removed everything as soon as we left.

The equipment from the People’s CDOT installation dismantled and placed on the sidewalk.

The incident highlighted an inherent issue with the actions of guerrilla activists like the People’s CDOT and Crosswalk Collective: the general lack of community approval. While the goals of these groups to ensure safe conditions for pedestrians and cyclists are no doubt noble, the way they go about doing so can be seen as unwanted, unasked for, illegal, and problematic.

One neighbor near the installation who spoke to The Daily Beast on the condition of anonymity criticized the effort, taking issue with “parachuting into a place to do something quickly without a lot of buy-in from the community.”

“What that speaks to is a lack of understanding,” the neighbor said. “And a lack of groundwork too.”

John doesn’t see it that way, though. To him and the rest of the People’s CDOT, what they’re doing is more than just mere vigilante activism, it’s addressing a profound failure by a society that prioritizes cars over people. It’s doubling down on radical safety measures in communities that desperately need it.

“We weren’t happy about it, but it doesn’t stop us from continuing our mission,” John said. “If anything, it only pushes us to do more, because we want to show Chicagoans what’s possible on their streets.”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.