Meet the man who plans to live to 180 (and has spent $2million trying)

By conventional wisdom, Dave Asprey is a squarely middle-aged man. He is 48, husband to one long-suffering wife, father to two school-aged children, and proud owner of a dollop of ash-coloured hair. He likes gadgets, gizmos, fine coffee and fitness trends. He has a podcast.

Conventional wisdom, however, is one of Asprey’s two principal bêtes noires. The other is ageing. And so he does not consider himself middle-aged at all. No, at 48, Asprey believes he is the world’s oldest young adult.

‘Yep, that’s how I see myself,’ he says, beaming into the camera on our Zoom call. ‘I’m at my 28 per cent birthday.’

He plans to live until about 180. The folly of youth, eh?

Dave Asprey is a biohacker. Or, as he puts it, he is ‘the father of biohacking’. A Silicon Valley investor and entrepreneur, for almost two decades he has pioneered the practice of applying the approach of a computer hacker to his own mind and body. Using tech innovations, wild self-experimentation and necessarily limitless supplies of optimism, biohackers believe they can reach levels of efficiency and longevity unprecedented in humans.

Nobody is more serious about it than Asprey, an American who says he has spent over $2 million ‘taking control of his own biology’, optimising his existence, reducing his biological age – and apparently adding 20 IQ points along the way.

Seventeen years ago, he was trekking in Tibet when altitude sickness rumbled him. Locals gave him traditional tea with yak butter in it. After a cup, Asprey felt his first, but certainly not last, rush of Messiah complex: he was a man resurrected.

Five years after the trek, he posted a recipe online, and he later launched Bulletproof coffee, a blended morning drink composed of brewed coffee, grass-fed butter and his added ingredient, MCT oil (a derivative of coconut oil containing fast-digesting fats). He declared it would make you feel energised, focused and full enough not to snack. A diet fad was born.

Within a few years, all the usual suspects were converted to Bulletproof – Silicon Valley types, moneyed fitness influencers, Hollywood stars. Asprey’s empire spawned dozens of products, diet books, a bricks-and-mortar coffee shop, and acolytes in David Beckham, Ed Sheeran and then Labour MP-turned-slimming icon Tom Watson.

Even the grande dame of celebrity pseudoscience, Gwyneth Paltrow, has given it a stamp of approval as it was served at her first Goop wellness summit.

Today, Asprey estimates that well over 150 million cups of his creamy, oily elixir have been consumed. He has an Instagram following of over 300,000, and has written books on everything from ageing to ‘winning at life’, plus a new one, Fast This Way, on fasting.

He claims his podcast, Bulletproof Radio, has been downloaded 175 million times, and, according to the internet, he is worth $27.5 million.

‘You shouldn’t believe what you read online, I don’t know where the hell those things come from,’ he says.

But you’re certainly solvent?

‘Oh, of course, I’m financially doing well, yeah.’

Life of a biohacker

It’s 7.30am on Vancouver Island, where Asprey lives with his wife, Lana, a doctor who runs a natural fertility and healthy pregnancy consulting practice – whom he met at an anti-ageing conference – and their children, Anna, 13, and Alan, 11. They have a small permaculture farm with sheep, chickens and ‘lots of vegetables’. He’s been up for one hour and 10 minutes, but seems hideously awake, and swigs from a cup of you-know-what.

‘This has prebiotic fibre, which is an innerfuel product we make, as well as MCT oil and butter. So I won’t be hungry. My last meal was 5.30pm last night, but I’ll be doing interviews until 2pm, so I’ll be doing an intermittent fast today, just because it’s convenient.’

There is nothing he does not monitor. When he’s finished playing with a Zoom filter that makes it look as if he has a moustache (an oddly simple augmentation to be moved by, considering he has had stem cells injected into his penis), I ask how he slept.

‘Let me check,’ he says, taking out his phone, which is connected to his chunky Oura Ring – a health tracker favoured in Silicon Valley and by Prince Harry. ‘Seven hours of sleep, two hours 10 minutes of deep sleep and one hour 23 minutes of REM. I would have loved another 20 minutes of REM, but I woke up early for this. So it’s your fault, man.’

In the background are lab instruments, oversized dials, a fake alligator skull and, of course, a coffee machine. This is Alpha Labs, his multimillion-dollar home office.

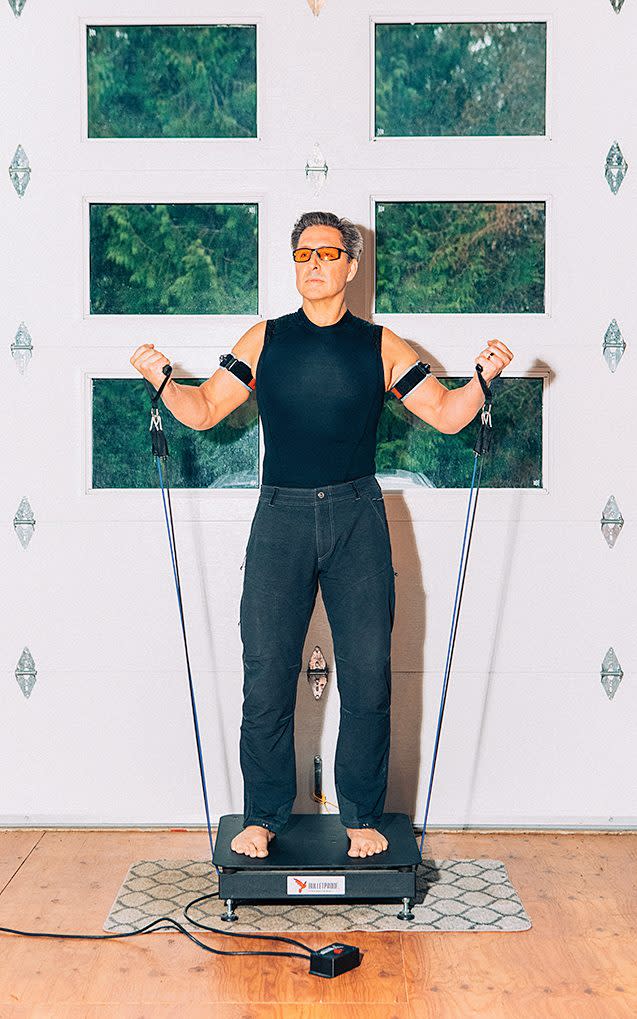

Downstairs is a cryotherapy chamber, an infrared-light bed, an atmospheric cell trainer that can take him to the top of Everest, and futuristic exercise machines that mean Asprey can do a two-and-a-half-hour gym session in 20 minutes. (I’m not sure how, either. Something to do with vibrations.)

I hope Asprey isn’t too heartbroken to read that he actually appears a little older than 48. Not that he looks haggard – he has a smooth complexion, a healthy tan, dimples you could park your car in – but there’s something unsettling about his head on such a glossy, ripped body. It’s as if Parker from Thunderbirds took his uniform off to reveal pierced nipples.

How to live forever

He made the ‘180’ claim a few years ago, and it’s followed him around ever since. Does he regret putting a number on it?

‘I don’t regret 180 at all,’ he says. ‘I just wish people would go, “Dave, you’re being too conservative.” Because, Guy, there’s a great chance you will live – and when I say “live”, I don’t mean in a wheelchair with tubes and diapers, I mean moving around under your own power, caring for yourself – with 100 years’ wisdom in your body and the energy of a person who is 35, 40. This is the world that’s coming, I know it in my bones, I can see it and I’m working to build it.’

The oldest person ever to live, Frenchwoman Jeanne Calment, supposedly lived to 122; another to 119. Asprey’s argument is that, with all the medical and technological innovations to come, 50 per cent more than 120 is a reasonable estimate – even for those of us without spare millions to spend on trying.

‘I think we could be looking at several hundreds of years for people. Now, is everybody going to live for several hundreds of years? Probably not. But if you look back to 1990, the only person who had a mobile phone spent $40,000 and everyone thought, “Who does this person think he is?” Well, now you can buy one for $1, right?

‘That’s how it works, it democratises. If you run a company making anti-ageing therapies, do you want to sell 2,000 of them to the billionaires, or two billion of them to everyone? This is just basic economics.’

From 'fat' to fit

Asprey wasn’t always like this. As a child in New Mexico, he experienced the gamut of ill health: during his teens he had arthritis in both knees, persistent nosebleeds and recurring strep throat. By his early 20s he was obese, had ‘man boobs’ and struggled to squeeze into an XXL T-shirt. At his heaviest, he weighed 21 stone.

Despite exercising for 90 minutes a day and restricting his calories, he says he struggled to shift weight, and in his late 20s, doctors apparently told him that he was at high risk for a stroke and heart attack. ‘Although I was not yet 30, I had a body more like that of a declining 60-year-old,’ he writes in his new book.

But he was clever; his parents, both scientists, instilled an interest in experiments, and Asprey soon began experimenting on himself. He tried a low-carb diet he’d read about in a bodybuilding magazine and shifted three and a half stone, spent $1,200 on ‘smart drugs’ to help his concentration and memory, and in the evenings researched all he could about optimising his body and brain.

Meanwhile, he had ventured into tech, apparently becoming the first person ever to sell something over the internet (a T-shirt with ‘Caffeine Is My Drug of Choice’ written on it) while still at college. By the time of that Tibet trek, he had worked for various tech companies, as a web engineer and director, and was an investor. He was fascinated with the idea that IT principles could be married to ‘New Age’ ideas to enhance life.

The sex journal

Asprey is, he says, ‘a fat computer hacker by training’ – which is where his qualifications in diet and nutrition begin and end. This riles his critics, but doesn’t bother Asprey, who is proudly self-taught and his own star patient, willing to investigate anything.

It’s why he once kept an ejaculation journal for a year, to work out how often men should orgasm. (Conclusion: no more than about once a week, though have sex as often as possible. Women, on the other hand, should orgasm as much as they can.)

It’s also why he’s probably had more stem cells injected into him than anybody else on the planet, variously to try to switch off inflammation, make injuries disappear or just reverse ageing. He’s had them in his legs, arms, neck, face, penis… A few weeks ago he Instagrammed a video of himself receiving a load in his buttocks.

‘That was just a touch-up. For the first couple of days [afterwards] my mental acuity was down, which is very unusual for me, but now I’m feeling really good.’

This is only part of Asprey’s routine. He sleeps around seven hours a night, rarely drinks alcohol (taking supposedly hangover-beating charcoal tablets if he does), and avoids long sessions of aerobic exercise, which he believes is inefficient.

How about supplements?

‘I take around 100 [a day]. Let me show you. You’ve reminded me that I haven’t taken them yet this morning.’

He produces what looks like one of those plastic bags you put your toiletries in at an airport, but filled with brightly coloured pills. Pouring a handful into his palm, he throws them back, then briefly resembles a seagull choking on a chip, before glugging San Pellegrino to wash them down.

‘There you go. That was half the bag. I’ll do the other half after we get off the call. But it’s not a big deal. The larger thing is knowing which ones to take.’

A decade’s worth of blood and urine testing has informed Asprey of his perfect cocktail of supplements, which includes vitamins A, C and D, plus K2 (for bone density), krill oil (for the brain, heart and skin), L-tyrosine (for mood) and methylfolate (for ‘brain power’).

In addition to that 100, he might pop a ‘smart drug’ like modafinil (which treats narcolepsy) if he’s, say, writing late into the night (in which case, by the way, he’ll wear special-lensed glasses so blue light doesn’t bother him). Then there are the small sprays of nicotine he applies to his tongue a few times a day. Smoking is bad, he says, but microdosing nicotine is a brain-enhancer.

The power of fasting

And so to fasting, the subject of Asprey’s new book. In 2008, though he’d lost seven stone from his peak weight, he was sick of the other fad diets, still craving biscuits and crisps, and felt a strange sense of emptiness, so took himself off to the desert in Arizona and lived in a cave, alone, consuming only water and dust for four days. Somehow he came back feeling fantastic.

Intermittent fasting was for him, but Asprey has since seen people ‘break themselves’ with fasting, by pushing themselves too hard. That’s why he wrote the book.

‘I have 10 years of experience, I’ve helped thousands of people through my channels, and I might as well share that.’

It is not aimed solely at hyper-functioning millionaires. Asprey even has some sympathy for people who succumb to the urge to eat three almond croissants before noon.

‘If you slept badly, or are in the middle of a fight with your partner, or you had a big workout, have some breakfast. But have some smoked salmon, or some protein and fat that is going to leave you feeling full until lunch,’ he says.

If you are ready to try a fast, start with a coffee with no sugar and no milk, he recommends. ‘That little bit of caffeine will double the production of fat-burning molecules in your body, ketones. And that turns off hunger. If you were to add MCT oil or grass-fed butter, well you’re not going to be hungry. You will not care about the croissant. Literally, you won’t even think about eating.’

What about lunch?

‘What’s for lunch? What’s for lunch?’ he mocks. ‘The average person’s thoughts are about 15 per cent about what’s for their next meal. If you do that little tweak in the morning, you will have 15 per cent more thoughts available to you.’

His wife Lana is a convert. Even his children are on board. They too drink Bulletproof coffee (albeit in small amounts).

‘My daughter does the biohacking and stuff. She’s like, “Daddy, I don’t understand why as soon as I get to school, they’re trying to make us have a snack. Don’t my friends have breakfast?” They’re not intermittent fasting, but they don’t experience cravings and distractions like normal kids, because they have enough for breakfast.’

Nutritional therapist Ian Marber is less convinced. ‘It’s not eating, and drinking black coffee, and if you drill that down, take away the “grass-fed” and whatever else, it’s a stimulant and fats. It makes sense, but there aren’t a great deal of studies into this – why would there be? It’s dull, unless you’re selling coffee,’ says Marber, who has over 20 years of experience and seems a little tired of self-taught lifestyle gurus.

‘These people come up with new names for things we’ve done for a long time. Like intermittent fasting. If you worked with someone in the 1980s, more likely a woman, who skipped breakfast and drank only black coffee, but said she was “dieting”, you’d be concerned by that behaviour. But call it “intermittent fasting” and it seems like something else.’

He sighs. ‘On the one side, we do eat too much and people can use fasting to lose weight. On the other, food is joyous, and food does not just represent fuel. To reduce it to something you have to control is a bit joyless.’

Asprey, for his part, is unbothered by naysayers and the critics he encounters online. ‘There are two kinds of critics. [There are] ones who say, “You know Dave, I looked at the data, and I have serious questions” – I’m like, let’s talk, I’m interested. Hard questions about my science, I dearly love it, I need more of that… But the typical critic is someone who was bullied in seventh grade and never got over it.’

He laughs. ‘And then they’ll say I’m a snake-oil salesman, to which I’ll usually respond with saying, “Yes, but it’s grass-fed snake oil, and it’s way better than that mouldy snake oil, would you like some?” Then they get really mad and run away.’

He certainly has enough confidence to last three lifetimes. And if he does make it to 2153, aged 180 but with the energy of a toddler on Tangfastics, who knows what he’ll have convinced us of.

I wonder about lasting that long, though. I expect I’d just be suicidally bored, especially if all my peers had died, leaving just me, a load of young space-people and a group of very smug biohackers born centuries ago. What would he do if, say, Lana didn’t make it?

‘Oh, she’ll be there. I basically said, “Hey, let’s race!”’ Asprey responds. ‘You know, it’s possible I’ll make some huge mistake, something I think is anti-ageing is pro-ageing, but I’ve been very accurate.’

A shrug. ‘We look younger, feel younger, and are metabolically younger than the average for our age. It seems to be working.’

Fast This Way: Burn Fat, Heal Inflammation, and Eat Like the High-Performing Human You Were Meant To Be, by Dave Asprey, is published on Thursday (HarperCollins, £14.99); preorder at books.telegraph.co.uk